Advances in PGPR Research

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Advances in PGPR Research

About this book

Rhizosphere biology is approaching a century of investigations wherein growth-promoting rhizomicroorganisms (PGPR) have attracted special attention for their ability to enhance productivity, profitability and sustainability at a time when food security and rural livelihood are a key priority. Bio-inputs - either directly in the form of microbes or their by-products - are gaining tremendous momentum and harnessing the potential of agriculturally important microorganisms could help in providing low-cost and environmentally safe technologies to farmers.One approach to such biologically-based strategies is the use of naturally occurring products such as PGPR.Advances in PGPR Research explores recent developments and global issues in biopesticide research, presented via extended case studies and up-to-date coverage of: · Low input biofertilizers and biofungicides used for sustainable agriculture.· Molecular techniques to enhance efficacy of microbial inputs.· Intellectual property issues in PGPR research. Written by an international team of experts, this book considers new concepts and global issues in biopesticide research and evaluates the implications for sustainable productivity. It is an invaluable resource for researchers in applied agricultural biotechnology, microbiology and soil science, and also for industry personnel in these areas.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.1 Introduction

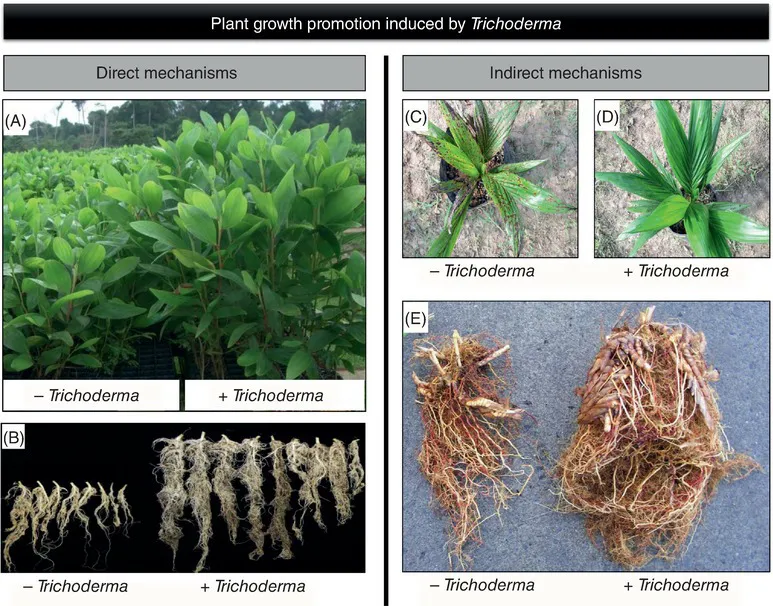

1.2 Trichoderma Plant Growth Promotion: Direct Mechanisms

1.2.1 Nutrient acquisition

Phosphate solubilization

Siderophores

Synthesis of secondary metabolites

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Mechanisms of Growth Promotion by Members of the Rhizosphere Fungal Genus Trichoderma

- 2 Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Phytostimulation

- 3 Real-time PCR as a Tool towards Understanding Microbial Community Dynamics in Rhizosphere

- 4 Biosafety Evaluation: A Necessary Process Ensuring the Equitable Beneficial Effects of PGPR

- 5 Role of Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms in Sustainable Agriculture and Environmental Remediation

- 6 Pseudomonas Communities in Soil Agroecosystems

- 7 Management of Soilborne Plant Pathogens with Beneficial Root-Colonizing Pseudomonas

- 8 Rhizosphere, Mycorrhizosphere and Hyphosphere as Unique Niches for Soil-Inhabiting Bacteria and Micromycetes

- 9 The Rhizospheres of Arid and Semi-arid Ecosystems are a Source of Microorganisms with Growth-Promoting Potential

- 10 Rhizosphere Colonization by Plant-Beneficial Pseudomonas spp.: Thriving in a Heterogeneous and Challenging Environment

- 11 Endophytomicrobiont: A Multifaceted Beneficial Interaction

- 12 Contribution of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria to the Maize Yield

- 13 The Potential of Mycorrhiza Helper Bacteria as PGPR

- 14 Methods for Evaluating Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Traits

- 15 The Rhizosphere Microbial Community and Methods of its Analysis

- 16 Improving Crop Performance under Heat Stress using Thermotolerant Agriculturally Important Microorganisms

- 17 Phytoremediation and the Key Role of PGPR

- 18 Role of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) in Degradation of Xenobiotic Compounds and Allelochemicals

- 19 Harnessing Bio-priming for Integrated Resource Management under Changing Climate

- 20 Unravelling the Dual Applications of Trichoderma spp. as Biopesticide and Biofertilizer

- 21 Genome Insights into Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria, an Important Component of Rhizosphere Microbiome

- 22 Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR): Mechanism, Role in Crop Improvement and Sustainable Agriculture

- 23 PGPR: A Good Step to Control Several of Plant Pathogens

- 24 Role of Trichoderma Secondary Metabolites in Plant Growth Promotion and Biological Control

- 25 PGPR-Mediated Defence Responses in Plants under Biotic and Abiotic Stresses

- Index

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app