![]()

1 Basics of Island Biogeography

It is one thing to make recordings or collections of butterflies from islands. Collecting has a long history but even so records for butterflies on British and Irish islands were, until recently, scattered in the journal literature (Dennis and Shreeve, 1996). However, it is another matter to make sense of the records. It was not until the early 1960s that sound scientific principles were established for island faunas. The present chapter provides an introduction to modern concepts in island biogeography, factors that affect the presence of butterflies, and other organisms, on British and Irish islands.

The Basic Model of Island Biogeography

In the 1960s, one of the most important breakthroughs in the ecological sciences was achieved; it was the publication of The Theory of Island Biogeography by Robert H. MacArthur and Edmund O. Wilson (1963, 1967). Although it was previously well understood that numbers of species on islands relate to island area and isolation, they demonstrated that the number of species could well reflect a dynamic equilibrium between two ongoing processes: (i) the immigration (viz. colonization) of species to an island; and (ii) their extinction ( Fig. 1.1a); as such, it is referred to as the equilibrium theory. It was a theory already foreseen by Eugene Gordon Munroe (1948) working on the butterflies of the West Indies. This was an astonishingly important breakthrough because, then, even mobile organisms such as butterflies were thought to have long occupied islands – including those comprising Britain and Ireland – on which they were found; as such, overseas transfers, apart from by known long-distance seasonal migrants (e.g. Vanessa cardui, Vanessa atalanta), were considered to be rare events. This dichotomy in perception must now seem very strange to modern readers; after all, if one species can with facility make the journey in numbers, then surely all others must have some capability of achieving the journey! In fact, this very belief was one of the stumbling blocks for challenging the long-held view that British butterflies survived the last major glaciation (Devensian, 20 k years (20 ka) BP) (Dennis, 1977). Yet, even then, sufficient evidence existed in the amateur journals that very small butterflies, including many sedentary butterflies, were capable of sea crossings (Dennis and Shreeve, 1996).

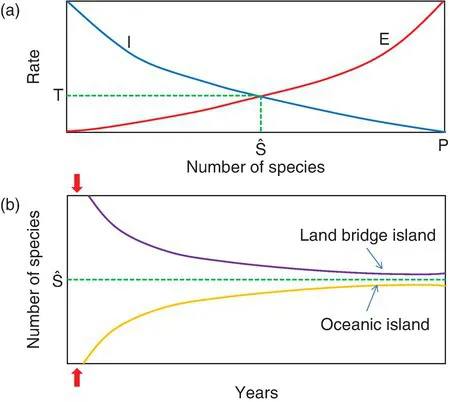

The mathematical model for a single island off a mainland source beautifully illustrates the basis for equilibrium in species numbers on islands (Schoener, 2010); a ‘steady state’ in numbers of species occurs where the gross extinction rate in species equals the immigration rate of new species. In Fig. 1.1, the rates are typically shown to be curvilinear, owing to the limit in the number of species at mainland sources: as numbers on an island grow, so does the probability of extinction; similarly, the probability of immigration and colonization will decline, as there are fewer new species left in the transfer pool. This observation is supported by ecological observations, for instance by: (i) the saturation of the species community with an increase in numbers of island species, leading to increased interactions (i.e. competition, predation, parasitization), thus smaller populations and extinctions (Wilson, 1969); and (ii) declining immigration rates as poorer dispersing species trail behind better dispersers (MacArthur and Wilson, 1967). Moreover, poorer dispersers are likely to be more vulnerable to extinction, owing to the link-up of colonization ability and migration capacity (Gilpin and Armstrong, 1981) (see also Chapter 3).

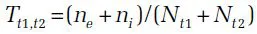

Equilibrium theory of numbers of species on islands, then, envisages a perpetual turnover in species; both immigration of new species and extinction of current species will have a characteristic mean rate and variance (unless conditions change significantly, i.e. through climate warming). It is perhaps useful to imagine the basic process taking place at an individual level. Consider that an island is being continually bombarded by individual butterflies and is simultaneously experiencing a continual loss of individuals (at all stages of development) (Simberloff and Wilson, 1971). Every so often an individual of a new species will arrive on the island and colonize it, or the population of a species will crash to zero and become extinct. Together, these processes describe the relative turnover rate (T) for an island’s species:

where t0, t1, t2 ... tm are time intervals (years), ne is the number of species extinctions on an island, ni the number of novel colonizations on an island, and N the total number of species at different times. T can be made into a percentage by multiplying by 100. Later, attention will be given to two types of island: (i) an oceanic island; and (ii) a land bridge island. Although Britain and Ireland do not have typical oceanic islands, they do have islands that simulate the conditions on a typical oceanic island, with an initial ‘start-from-scratch’ condition of zero species as in the case of Hawaiian islands emerging as volcanic mounds over an oceanic mantle ‘hot spot’ (Funk and Wagner, 1995). In the case of some British islands a number emerged offshore with deglacial isostatic rebound (see Chapter 2) of ice-laden land, their fauna wiped out by glacial tabula rasa and/or marine inundation during the last major ice advance (c. 20 ka BP). In the case of these two types of islands, very different patterns of colonization emerge, continuous gains towards an equilibrium with an ‘oceanic’ island and continuous losses to an equilibrium in the case of a vicariant land bridge island ( Fig. 1.1b). These conditions describe extremes of what is found in nature; it will become evident that Britain displays more complex scenarios.

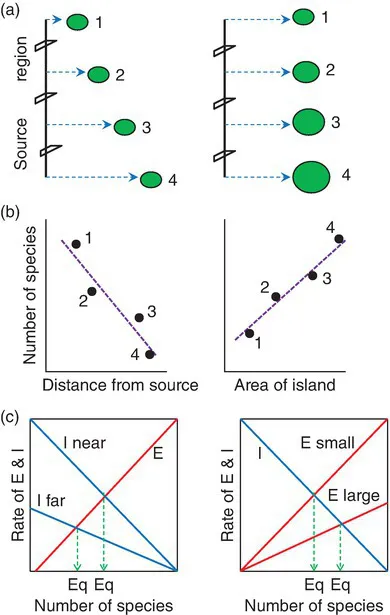

The intriguing picture of equilibrium theory is that large and small islands, near-to-source and isolated islands, have very different equilibria ( Fig. 1.2); the curve for extinctions is higher for small islands than large islands, and the curve of immigration for isolated islands is lower than that for near islands. This has consequences for both the number of species and absolute turnover rates: (i) near islands (having the same area) and large islands (experiencing the same degree of isolation) have more species than far, small islands; and (ii) absolute turnover (not relative turnover) is greater for near than far islands (of the same area) and for small than large islands (of the same degree of isolation) ( Fig. 1.2). Altogether, this puts isolated small islands at a huge disadvantage in terms of comparative numbers of species. In fact, the two processes of colonization and extinction have far more profound implications for their island faunas, ones that affect the communities, adaptation and evolution of their faunas (see Chapter 8).

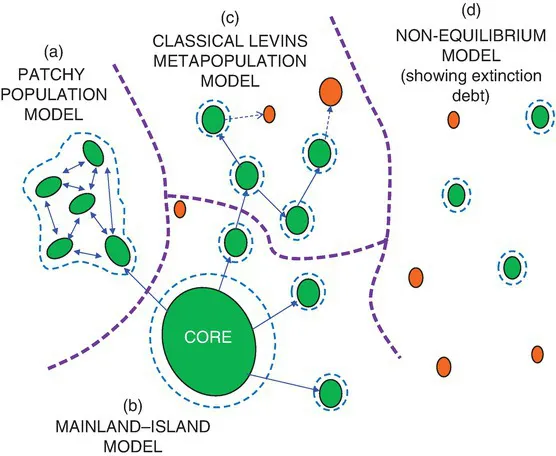

The picture of single islands lying offshore a mainland is, of course, a simple one. Often there are archipelagos (e.g. Isles of Scilly; Outer Hebrides), and these too may be close to a mainland shore or isolated. It is at this level that one can appreciate not just how complicated island biogeography can be, but also how important equilibrium island biogeography theory has become: archipelagos lie at the root of metapopulation biology (habitat islands simulating islands lacking a mainland source); the equilibrium models for them were developed by the remarkable scientist Ilkka Hanski and his team (Hanski, 1994; Hanski and Gilpin, 1997). A variety (gradient) of metapopulation models may be conceived from patchy populations to mainland–multiple island situations and extinction debt metapopulations (Dennis, 2010); all these models are relevant for different butterfly species on groups of small offshore islands in Britain and Ireland ( Fig. 1.3).

A Broader View of Island Faunas

The equilibrium model, in providing such a neat picture of species numbers and turnover, is highly seductive; but it has been the subject of long and heated debate (Lomolino et al., 2010). When reviewing papers that deal with this subject it is important to distinguish two related issues: (i) the balance of immigrations (colonizations) and extinctions which defines a steady state (equilibrium) in species numbers ( Fig. 1.2c); and (ii) the relationship of numbers on islands in any study region to island area and isolation, on which an equilibrium view is based ( Fig. 1.2b).

The critical property of equilibrium theory is that extinction rate equals colonization rate. This has to be the case for every island in a study region (i.e. herein, British and Irish islands). It is not difficult to envisage circumstances that generate a non-equilibrium condition for a specific island or islands. Non-equilibrium may occur owing to: (i) relatively too few extinctions (i.e. extinction debt); (ii) a sudden extinction event affecting the island’s fauna; (iii) relatively low colonization rate (i.e. an immigration backlog or lag in immigration rate; e.g. following glacial tabula rasa); (iv) a surfeit of immigration (i.e. increased rate of immigration; e.g. owing to an external stimulus such as climate change or a weather event); and (v) a relatively high species accumulation, i.e. autochthonous speciation (e.g. molluscs on Madeira) (Cook, 2008; Kier et al., 2009).

A linear (semi-log, or log-log) relationship between species numbers on islands and island area and/or island isolation ( Fig. 1.2b) is typically advanced as an indication of an equilibrium condition. In fact, the absence of a neat linear relationship is not evidence of the absence of an equilibrium, but it is evidence that island area and/or isolation are compromised by other factors affecting inter-island extinction rates and colonization rates on some or all of the islands. It is well to bear in mind that an island’s ‘resources’ may supplant area in importance, as has been found to be the case with butterfly metapopulations (Dennis and Eales, 1997, 1999), ...