![]()

1 The Role of Water in Plant Life

1.1 Functions of Water in the Plant

In some ways the life of plants is much more directly dependent on water than is life in the animal kingdom. One reason for this is that higher plants differ from animals because nearly all are nutritionally self-sufficient, or autotrophic. Water serves as a hydrogen donor and thereby as a building block for carbohydrates, which are synthesized by plants making use of sunlight (Box 1.1). Another inorganic building block used by plants in the synthesis of organic primary products is carbon dioxide (CO2), which plants can only take up from the atmosphere at the same time that they return water vapour to the atmosphere. This exchange of gases is necessary because, during their evolution, plants never developed a membrane that was permeable to CO2 but impervious to water vapour. For the exchange of these two gases there are special openings in the leaf epidermis called stomates. The contra-flow gas exchange of water vapour and CO2 that takes place between the inside of a leaf and the atmosphere through the stomates is therefore unavoidable. If the exchange of gases is to be maintained for the production of dry matter, growth and development, plants require a continual supply of water in liquid form. This is particularly true for plants other than succulents and halophytes, since the internal store of water is normally very small relative to the daily loss. The steady use of water demands its continual uptake.

There is another reason why plant life is immediately dependent on water. In contrast with animals, land plants live permanently in one place, so they have to remove water from the soil water reservoir in their immediate vicinity. Plant life depends essentially on water that is stored within the soil and is available for extraction. For extraction of water, plants rely on their root systems, which continue to grow through most of their life. The quality of the soil as a store of water accessible to roots depends on texture and structure.

The daily throughput of water, that is the removal of water from the soil by roots, its movement through the plant in liquid phase, and its final transfer to the atmosphere in the vapour phase, can amount to a considerable quantity in comparison with the mass of the plants involved. In the middle of June, 1 week before heading, the dry weight of an oat crop amounted to 400 g m–2 (4 t ha–1). The daily water use at this stage of development was equivalent to 6 mm of precipitation, which in this case came from the soil storage (Ehlers et al., 1980a). These 6 mm of water throughput convert into 6 l or about 6 kg of water m–2 or 60,000 l (approximately 60 t) ha–1. Hence, relative to the dry mass of the standing crop, 15 times more water was returned to the atmosphere on a daily basis. Assuming that 85% of the shoot mass was water, the oat crop contained 2270 g water m–2. Compared with this store of water in the shoot, 2.6 times more water was extracted from the soil and passed on to the atmosphere. This transfer of water by plants to the atmosphere in the form of vapour is called transpiration.

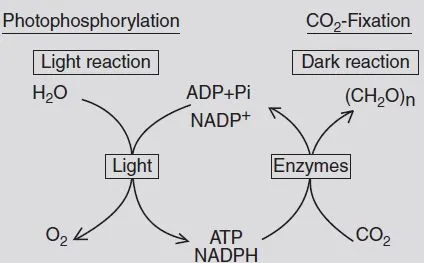

Box 1.1. Light and water – prerequisites of photosynthesis

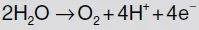

In the so-called light reaction of photosynthesis water is split into oxygen, protons and electrons:

The oxygen produced moves out of the plant by diffusion preferentially through the stomates. At the same time during this light reaction nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) is reduced to NADPH and in a coupled process adenosine diphosphate (ADP) is phosphorylated by use of inorganic phosphate (Pi), forming the ‘energy-rich’ adenosine triphosphate (ATP). NADPH and ATP as well as enzymes bring about the fixation of CO2 in the so-called dark reaction. In this reaction CO2 is reduced, ATP is dephosphorylated and NADPH is oxidized. The CO2 gets assimilated, and organic compounds can then be built (Fig. B1.1).

The enzyme involved in the primary process of CO2 assimilation is known as ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) carboxylase. That is true for the C3 plants (see Section 1.2), but for the C4 plants it is another enzyme, named phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase. The latter enzyme is also involved in CO2 assimilation by certain succulent plants. These plants have the capability of crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM).

Clearly we can say that the demands of plants cannot be satisfied with a small amount of water. Certainly it can be said that nature allows plants to be prodigal with this resource. The amount of water that is transpired daily by plants is generally 1–10 times more than the water stored in them. Compared with the amount needed for cell division and cell enlargement, the amount is 10–100 times more, and finally compared to the needs for photosynthesis it is 100–1000 times greater. So that prompts the question: ‘Why is all the water taken up?’

Water is an important constituent of all plants. Roots, stems and leaves of herbaceous plants are 70–95% water. In contrast, water comprises only 50% of ligneous tissues and 5–15% of dormant seeds.

Water is the basis of life for a single cell and for the aggregate of cells that combine to form the structure of higher plants. It not only influences the processes and activities of cell organelles, but can also determine the final appearance of a plant. As a chemical agent it takes part in many biochemical reactions, for instance in assimilation (Box 1.1) and respiration. It is a solvent for salts and complex molecules, and mediates chemical reactions. Water is the medium of transport for nutrient elements and organic molecules from the soil to the root and the means of transport of salts and assimilates within the plant. Stimulation and motion of organelles and cell structures, cell division and elongation are examples of processes controlled by hormones and growth substances, with water being the carrier of these messengers, enabling the regulatory system of the plant.

Other functions of water are much more apparent. Water confers shape and solidity to plant tissues. If a previously sufficient supply of water is disrupted, herbaceous plants and plant organs that lack supporting sclerenchyma will lose their strength and wilt. The hydrostatic pressure in cells is dependent on their water content, and permits cell enlargement against pressure from outside, which originates either from the tension of the surrounding tissue or from the surrounding soil. Root tips experience a confining pressure when penetrating soil because the particles, held together by cohesive and adhesive forces, have to be pushed apart to allow the root to penetrate. The large heat capacity of water greatly dampens the daily fluctuations in temperature that a plant leaf might otherwise undergo, due to the considerable amount of energy required to raise the temperature of water. Energy is also required to convert liquid water to a vapour that transpires from leaves causing cooling due to evaporation. Without these temperature compensating effects, plants would warm up much more and eventually die from overheating. Interestingly, because of these effects, transpiration rates can be estimated from surface temperatures, obtained by infrared thermography, either immediately within the crop stand (Section 14.1) or using remote sensing from aeroplanes or satellites.

1.2 Adaptation Strategies of Plants to Overcome Water Shortage

Depending on the amount and distribution of rainfall and the probability of occurrence, the regions of the world vary greatly in the supply of water. The support to plant life ranges from great abundance to extreme poverty. Plants have developed various strategies to counter the problems of temporal or spatial water shortage.

According to the presence and supply of water, ecologists divide terrestrial plants into hygrophytes, mesophytes and xerophytes. Hygrophytes are plants that thrive in generally humid habitats, where there is no shortage of water throughout the growing season. In temperate zones, in addition to these plants with a humid biotype, there are many shade-loving herbaceous forest species that also belong in this category.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the xerophytes. These plants are adapted to water shortage, which may occur regularly and may persist over long periods of time. Anatomical and physiological specialization has taken place to meet the requirements of these plants so that they can survive extended periods of water scarcity. To this group belong succulent plants that establish an internal water reservoir for use during dry spells, thereby postponing desiccation. Another group of xerophytic plants are able to endure considerable water loss from their tissues without losing their ability to survive.

Mesophytes fit in between these two extremes. Many plants from temperate climates belong to this group, but the cultivated plants from those regions are also included. The latter cannot endure an extreme form of arid climate without being irrigated. However, they are well prepared for short periods of water shortage. When water supply falls short, they can reduce their transpiration rate dramatically and modify other processes.

Weather patterns may result in temporal and spatial shortages in water supply with varying intensity. As mentioned earlier, rainfall is a principal factor responsible for limitations in the plant water supply. But water shortages depend also on a second climatic var...