![]()

1 The Nuts and Bolts of Olfaction

NICOLAS MEUNIER1,2 AND OLIVIER RAMPIN1

1Neurobiology of Olfaction, INRA, Université Paris-Saclay, Jouy-en-Josas, France; 2Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin, Versailles, France

A living being does plenty of things with the information conveyed by the presence of an odour. One of the most basic needs is food, which can be recognized through chemical signature cues. Odours also play a major role when looking for a mate. Many animals will rely mainly on olfaction to initiate reproduction; this is the case in most domesticated species. Animals will also use olfaction to orientate themselves, to create social bonds as well as to avoid predators and imminent threats such as fire. In this chapter, we will present the basic information to understand how olfaction works and an overview of its importance in animal behaviour.

What is an Odour?

Living beings need to detect information in their environment to interact with it. Many different types of information are accessible, such as those conveyed by concentration of molecules, pressure, light, heat, and electric or magnetic fields. The simplest and probably the first system that developed during the course of evolution is the detection of molecules in the environment. While this ability appears obvious in animals, it is shared by all living beings. Indeed, most bacteria are able to detect a new source of energy such as lactose in the absence of glucose and can adapt their metabolism to use it. Some bacteria can even perform complex communication through molecule exchanges (Waters and Bassler, 2005). Similarly, plants detect molecules released by neighbouring conspecifics eaten by herbivores and produce in response various compounds to reduce their own attractiveness to herbivores (Karban et al., 2013). However, in the following we will concentrate on odours and olfaction in relation to the animal kingdom.

Can all volatile molecules be defined as an odour? An odour is first of all a mixture of molecules (each referred to as an odorant) that is different from its surrounding (air and water do not smell) and that triggers a sensation in the animal detecting it. An odour is defined by the nature and the concentration of odorants that are present in it. Natural odours like those released by animal fluids (such as sweat, urine, saliva and tears) contain hundreds of odorants with very different chemical properties: acids, aldehydes, ketones, etc. An odour allows the identification of its source based on the variety of odorants present. As odours are conveyed in the form of a complex airflow (referred to as plumes) in the air or currents in water, it also contains information about the distance to the source, and time elapsed since it has been released. The concentration of a single odorant changes at each time point and at each location point of a given milieu. The complexity of this information suggests that the olfactory system is adapted to this spatiotemporal dynamic.

In a laboratory setting, it is difficult to control this heterogeneity of smells originating from the variety of odorants, their concentration and their spatiotemporal dynamic. Therefore, research labs often use a small number of odorants, prepared in a limited number of concentrations to study the response of an organism. In humans, one odorant (i.e. a single molecular compound) is often sufficient to be perceived as an odour, e.g. isoamyl acetate is recognized as banana odour. We use this property in laboratories to simplify experiments assuming that it holds true also for non-human animals.

There are puzzling data about odorants and odours. Experiments in humans reveal that the smell of a molecule is very different depending on its concentration, ranging from pleasant to unpleasant and finally irritant. For example, heptanoic acid is pleasant at low concentrations around 105 diluted in mineral oil, reminiscent of cheese, whereas at higher concentration (around 103 dilution) the smell will resemble your socks after you have just finished jogging on a hot day. Finally, heptanoic acid is impossible to smell when only 10 times diluted as it will immediately cause you to block your respiration. Furthermore, while some molecules with different chemical structures are perceived as the same odour, some molecules that are mirror images of each other (enantiomers) are distinguished after some training even for those not blessed with a good nose. Although correlations are found between molecular features of an odorant and its perceived intensity, pleasantness and familiarity (Keller and Vosshall, 2016), there is no unique relationship between an odorant and the odour it is associated with. Finally, both in humans (Livermore and Laing, 1996) and rodents, odorant discrimination within an odour remains poor. In other words, neither rats nor humans are good at answering the question ‘How many odorants are there in this odour?’

The detection of an odour is the job of olfaction, one of the five senses of humans, and it goes along with taste (or gustation), which is more directed towards the detection of food qualities during ingestion. Both are commonly grouped under the term of chemical senses because they allow the detection of chemicals in the environment. Their distinction can be tricky especially for species living in water. In the following, we will focus our attention mainly on the terrestrial animal world.

How is an Odour Detected and Processed by the Nervous System?

The molecular basis of odour detection

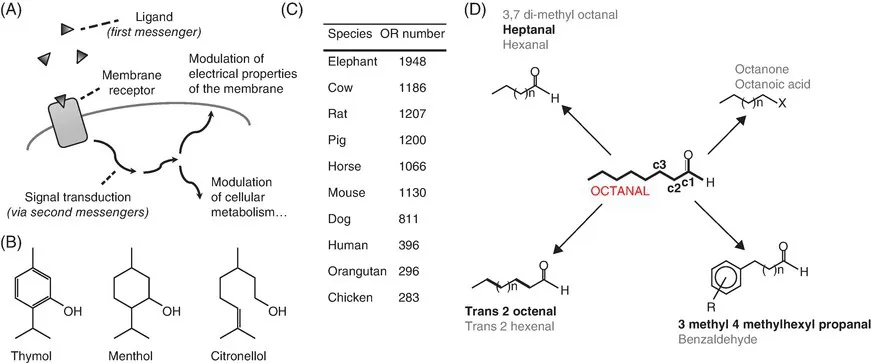

To start at the very beginning: animals are built from elementary structures called cells. The frontier between a cell and the outer world is the membrane maintaining the integrity of the cell. This protection leads to isolation from the environment, which is far from optimal when you need to interact with it. Thus, all cells produce on the surface of their membrane transporters to exchange molecules and receptors to interact with the environment. Part of each receptor is exposed to the extracellular compartment. It is this part that will bind, reversibly, the molecules of the environment such as odorants. By binding molecules to membrane receptors, cells obtain information from their environment. Some molecules bind to the receptor even when they are present at low concentration. These molecules have a high affinity for the receptor. They are referred to as ligands. Through binding, the shape of the receptor changes, which drives a signal into the cell. Figure 1.1A describes this mechanism, which is called signal transduction because it transduces (converts) an external signal (here a molecule at a given concentration) into an internal signal.

The binding of an odorant to a receptor is facilitated by the movement of the molecule in the environment and the behaviour of the animal. A sniff, which changes the flux of air that enters the nostrils, and redirects air in the nasal cavity towards the olfactory epithelium, improves odorant detection. In animals, the olfactory receptors that bind odorants are present in the membrane of specialized cells called olfactory neurons. Olfactory receptors and olfactory neurons refer thus to two different things that are easy to confuse. The olfactory receptors are the membrane proteins binding odorants. The olfactory neurons are the first order neurons of the olfactory system.

The largest family of receptors in the genome

Industrial chemistry has synthetized new molecules that were previously absent on earth, and among these are thus potentially new odorants. Astonishingly, as long as these molecules are volatile, they can activate the olfactory system, despite never having existed during the evolution of this system. The combinatory range of organic molecules is huge, indicating that the olfactory system discriminates among tens of thousands of different odorants. Furthermore, this discrimination is very subtle as we are able to distinguish very similar molecules (Fig. 1.1B), even between enantiomers (the same molecule but arranged differently in space, just like our two hands). This capacity is very similar to the immune system’s ability to fight pathogens. Indeed, the immune system needs to recognize an immense diversity of pathogens, some of them never encountered before. Similarly to the immune system, the olfactory system deals with molecular diversity and specificity of recognition by having a great variety of olfactory receptors and a combinatory system.

In mammals, the genome contains approximately 30,000 genes. Around 5% encode for olfactory receptors, which is huge, making olfactory receptors the largest receptor gene family (Buck and Axel, 1991). Among terrestrial vertebrates, elephants, horses and cows have the greatest number of olfactory receptors, while birds and primates have the lowest (Fig. 1.1C). This diversity appears to be consistent with the olfactory capacities of a given species, as this number decreases according to the importance of olfaction among the different senses (Niimura et al., 2014). Elephants, with their 2000 olfactory receptors, rely heavily on olfaction especially for sexual behaviour. They are among the few known mammals in which odorant molecules drive behavioural responses before and during mating (Rasmussen and Greenwood, 2003). Nevertheless, primates with their great visual system or platypuses endowed with a keen electric field sense still have about 400 functional olfactory receptors. It is also worth noticing that birds in the past have been wrongly considered as having poor olfaction, whereas they are in fact no worse than many mammals, with almost 300 olfactory receptors for the chicken. However, no clear relationship can be found between olfactory ability to detect low concentration of odorants and olfactory gene numbers. Furthermore, olfactory capacities and sensitivity also depend on training as humans can develop a very acute sense of smell (e.g. perfumers, sommeliers and oenologists).

Only a few olfactory receptors have been characterized in terms of which molecules they recognize, and most studies have been performed in mice due to the genetic tools available. These results show that, overall, some olfactory receptors can be activated by molecules sharing structural similarities (Fig. 1.1D), while others are very specific, being activated by one particular molecule (Araneda et al., 2000; Saito et al., 2009). A key point to understanding how olfaction distinguishes among tens of thousands of different molecular compounds is the fact that an olfactory neuron expresses only one of the hundreds of olfactory receptors available in the genome.

First step . . . the olfactory epithelia

Olfactory neurons are distributed over the whole olfactory epithelium in the nasal cavity (Fig. 1.2A–C). In vertebrates, two major epithelia are implicated in odour detection: the main olfactory epithelium and the vomeronasal epithelium (often referred to as the vomeronasal organ). The latter has long been thought to have appeared with terrestrial life but recent studies indicate that there was already segregation of those two systems in early forms of vertebrates such as lamprey (Ubeda-Bañon et al., 2011). Although the vomeronasal organ exists in all mammals, it regresses at the end of the embryonic development in bats, cetaceans and most primates including humans (Mucignat-Caretta, 2010). In terrestrial animals, the vomeronasal organ is specialized in the detection of molecules present in body secretions that are usually not very volatile. Thus, the animal must be in direct contact with the source in order to detect these molecules. For a long time, the two systems have been considered complementary: the detection of odours carrying general information was performed by the main olfactory epithelium, whereas the vomeronasal organ was thought to be specialized in the detection of odours, the famous pheromones, released by individuals from the same species and eliciting innate behaviours (see Chapter 3). Recent studies show that both epithelia participate in pheromone detection (Leypold et al., 2002; Mandiyan et al., 2005), and both epithelia also share the same structure. They are composed of olfactory ne...