- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This 3rd edition highlights many advances in the field of seed ecology and its relationship to plant community dynamics over recent years. It features chapters on seed development and morphology, seed chemical ecology, implications of climate change on regeneration, and the functional role of seed banks in agricultural and natural ecosystems.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Seeds by Robert S Gallagher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Agronomy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Overview of Seed Development, Anatomy and Morphology

Introduction

The spermatophytes, comprised of the gymnosperms and angiosperms, are plants that produce seeds that contain the next generation as the embryo. Seeds can be produced sexually or asexually; the former mode guarantees genetic diversity of a population, whereas the latter (apomictic or vegetative reproduction) results in clones of genetic uniformity. Sexually produced seeds are the result of fertilization, and the embryo develops containing, or is surrounded by, a food store and a protective cover (Black et al., 2006). Asexual reproduction is probably important for the establishment of colonizing plants in new regions.

Seeds of different species have evolved to vary enormously in their structural and anatomical complexity and size (the weight of a seed varies from 0.003 mg for orchids to over 20 kg for the double coconut palm (Lodoicea maldvica)). Nevertheless, their development can be divided conveniently into three stages: Phase I – formation of the different tissues within the embryo and surrounding structures (histodifferentiation, characterized by extensive cell divisions); Phase II – cell enlargement and expansion predominates (little cell division, dry weight increase due to reserve deposition, water content decline); and Phase III – dry matter accumulation slows and ceases at physiological maturity (Black et al., 2006). In many species, physiological maturity is followed by maturation drying as the seed loses water to about 7–15% moisture content and becomes desiccation tolerant (orthodox seeds) and thus able to withstand adverse environmental conditions. At this stage a seed is quiescent (expressing little metabolic activity); in some cases it may also be dormant. In contrast, some species (about 7% of the world’s flora, e.g. water lily (Nymphaea spp.), chestnut (Aesculus spp.), sycamore (Acer spp.), coconut (Cocos nucifera), Brazilian pine (Araucaria angustifolia)) produce recalcitrant seeds that do not undergo maturation drying and are desiccation sensitive at shedding. These seeds rapidly lose viability when water is removed by drying and therefore are difficult to store.

Pollination and Fertilization

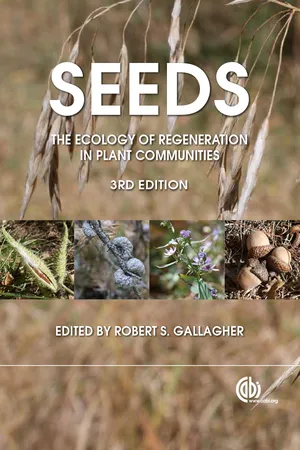

In seed plants, the female gametophyte (embryo sac, megagametophyte) is located within an ovule, inside the pistil. It is surrounded by one or two integuments and the nucellus (megasporangium; Black et al., 2006). In the Polygonum type, the developmental pattern exhibited by most angiosperm species, the embryo sac is formed when a single diploid (2n) cell (megasporocyte) in the nucellus undergoes meiosis (reduction division) which results in the production of four haploid (n) megaspores. Three of them undergo programmed cell death (PCD) and the remaining one undergoes mitosis three times, without cytokinesis, to produce a megaspore with eight haploid nuclei (Yadegari and Drews, 2004). Subsequently, cell walls form around these, resulting in a cellularized female gametophyte. During cellularization, two nuclei (one from each pole) migrate toward the centre of the embryo sac and fuse, resulting in a diploid central cell. Three cells that migrate to the micropylar end of the embryo sac become the egg apparatus with an egg cell (the female gamete) in the centre flanked by two synergids, and the remaining three are located to the opposite (chalazal) end forming antipodal cells (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1. Double fertilization in an angiosperm ovule. (a) Arrangement of cells in the mature embryo sac and in the pollen tube prior to fertilization. (b) Pollen tube enters the micropyle, with two sperm cells to be released to effect double fertilization. (c) Sperm cells are released from the pollen tube into a degenerated synergid cell flanking the egg cell and (d) they migrate to the egg cell and central (polar) cell resulting in: sperm cell (n) + egg cell (n) → zygote (2n) → embryo (2n); and sperm cell (n) + central cell (2n) → endosperm (3n). (From Purves et al.,1998.)

Male gametes (sperm cells) are produced as pollen grains inside the pollen sacs in the anthers (microsporangia). A mature pollen grain contains a large haploid vegetative (tube) cell and a smaller haploid generative cell that divides mitotically and produces two sperm cells.

Pollination involves the transfer of pollen grains to the stigma, the receptive surface of the pistil, which is followed by growth of a pollen tube through the style to the egg cell. Pollination can take place within the same plant (self-pollination, autogamy) or the pollen can be delivered from a different plant (cross-pollination, allogamy). Autogamy leads to the production of true-to-type offspring; this is disadvantageous when selfed offspring harbour recessive traits, but it may be advantageous for reproduction under unfavourable environmental conditions (Darwin, 1876). On the other hand, allogamy can introduce traits that increase resistance to diseases and predation, as well as seed and fruit yield. To prevent self-pollination and to promote the generation of genetic diversity, plants often exhibit self-incompatibility (SI), which causes the rejection of pollen from the same flower or plant. In many angiosperms, SI is controlled by a single multi-allelic locus S; incompatibility occurs when there is a match between the S alleles present in the pollen and style (Golz et al., 1995). SI is determined by a protein secreted over the stigma surface, or in the style, which is a barrier that prevents pollen germination or pollen tube penetration through the style.

While pollination can be effected by wind, water or insects (sometimes by animals such as bats or birds), the majority (over 70% of angiosperms) depend upon insects for cross-pollination (Faheem et al., 2004). The effectiveness of pollinators depends upon flower characteristics such as colour, scent, shape, size and nectar and pollen production. Wind pollination probably evolved from insect pollination in response to pollinator limitation and changes in the abiotic environment, especially in families with small, simple flowers and dry pollen (Culley et al., 2002).

When pollen comes in contact with the stigma, it adheres, hydrates and germinates by developing a pollen tube. The two immotile sperm cells are carried by tube tip growth to the embryo sac (Lord and Russell, 2002). Fertilization involves two male gametes and therefore is called double fertilization. This occurs by discharge of the sperm nuclei from the pollen tube and their delivery into the embryo sac, whereafter one fuses with the egg cell nucleus and the second with the two polar nuclei of the central cell (Fig. 1.1; Hamamura et al., 2012). As a result, a diploid embryo cell (zygote) and a triploid endosperm cell are created.

The embryo (Greek: embryon – unborn fetus, germ) is the future plant, and the endosperm, which may or may not be persistent, supplies nutrition to it. A single embryo usually develops per seed, although polyembryony occurs in some species (see next section).

Apomixis

Apomixis is a type of asexual reproduction, in which there is embryogenesis without the prior involvement of gametes; it occurs in about 35 families of angiosperms, including the Asteraceae (e.g. dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)), Rosaceae (e.g. blackberry (Rubus fruticosus)), Poaceae (e.g. Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis)), Orchidaceae (e.g. Nigritella spp.) and Liliaceae (e.g. Lilium spp.). Its role in evolution is incompletely understood (Carneiro et al., 2006). This type of reproduction leads to the formation of offspring that are genetically identical to the maternal plant, although they tend to maintain high heterozygosity. There is no meiosis prior to the embryo sac formation (apomeiosis), and double fertilization does not occur, even though there is often normal pollen production. There are two types of apomictic development, sporophytic and gametophytic.

Sporophytic apomixis (adventitious embryony) is initiated late in ovule development and usually occurs in mature ovules (Bhat et al., 2005). The embryo is formed directly from individual diploid cells of the nucellus or inner integument (cells external to the megagametophyte) and is not surrounded by the embryo sac. The formation of the endosperm occurs without fertilization of the central cell (autonomously). Most genera with adventitious embryony are diploids (2n = 2x). This type of apomixis is mainly found in tropical and subtropical woody species with multiseeded fruits (Carneiro et al., 2006).

In gametophytic apomixis the megagametophyte develops from an unreduced (usually diploid) megaspore (diplospory) or from a cell in the nucellus (apospory; Bhat et al., 2005; Carneiro et al., 2006). In contrast to adventitious embryony, the cell that later develops into the embryo, after three mitotic divisions, forms a megasporophyte-like structure, similarly to during sexual reproduction. However, there is no fusion of female and male gametes, and the diploid egg cell develops by parthenogenesis (autonomously) to form an embryo. Endosperm development can be autonomous or it requires fertilization of the central cell (pseudogamous). Most plants with gametophytic apomixis are (allo) polyploids (2n > 2x), while the members of the same or closely related species that reproduce sexually usually are diploids. Diplospory is dominant in the Asteraceae and apospory in the Poaceae and Roseaceae.

Most apomicts are facultative because they retain their capacity for sexual reproduction. Depending on the mode of apomixis, the events of sexual reproduction might occur in the same ovule or in different ovules of the same apomictic plant (Koltunow and Grossniklaus, 2003). In many species apomixis is associated with polyspory or polyembryony (Carneiro et al., 2006). In polysporic (bisporic or tetrasporic) species, ovule development is disrupted, but a reduced egg cell is formed and its fertilization occurs. In polyembryony multiple embryos are formed in one ovule, either from the synergids as a result of there being multiple embryo sacs in an ovule, or by cleavage of the zygote cells. Thus seeds with more than one embryo are produced; this polyembryony can be indicative of apospory or adventitious embryony. It is characteristic of Poa, Citrus and Opuntia spp., and of conifers such as fir (Abies spp.), pine (Pinus spp.) and spruce (Picea spp.).

One of the advantages of apomixis is that there is assured reproduction in the absence of pollinators, and it is a phenomenon often restricted to narrow ecological niches or challenging environments. Disadvantages include the inability to control the accumulation of deleterious genetic mutations, and lack of ability to adapt to changing environments.

Embryogenesis

During embryogenesis the central portion of the megagametophyte breaks down to form a cavity into which the embryo expands (Bewley and Black, 1994). The time it takes for the embryo to develop varies among different species and can be from several days to many months, even years. It also is influenced by the prevailing environmental conditions. Early embryo development includes the acquisition of an apico-basal polarity, differentiation of the epidermis and the formation of a shoot and root meristem (Dumas and Rogowsky, 2008). Polarity is established after the first division of the zygote. Polarity is usually perpendicular to the embryo axis and is asymmetric; a basal and apical cell are created.

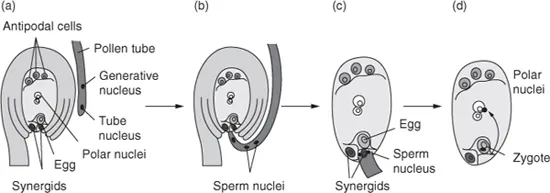

In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), a model dicot, the two-celled embryo undergoes a number of mitotic divisions leading to the formation of a suspensor, root precursor and a proembryo (Black et al., 2006). The suspensor facilitates the transport of nutrients from the endosperm to the embryo and undergoes PCD as the embryo matures. Its uppermost cell produces the root meristem. During development the embryo progresses through the globular, heart and torpedo stages to reach maturity (Fig. 1.2). During the transition from the globular to the heart stage the cotyledon structure and number are established. The mature embryo consists of two cotyledons borne on a hypocotyl, the collet (hypocotyl–radicle transition zone) and the radicle; seed desiccation then occurs.

Fig. 1.2. Stages of development of a dicot embryo from the fertilized egg cell (zygote), as typified by Arabidopsis thaliana. Initially this cell divides to form an apical and a basal cell (not shown); the former divides to become the embryo (EP) and the latter the suspensor (S), as is evident at the preglobular stage. The protoderm (Pd) develops into the epidermal layer (Ed) of the mature embryo, the ground meristem (Gm) into the storage parenchyma (P), the procambium (Pc) into the vascular tissue (V) and the hypophysis (Hs) into the root and shoot meristems (RM, SM). A, axis; C, cotyledons. (From Bewley et al., 2000.) Reproduced with permission of the American Society of Plant Biologists.

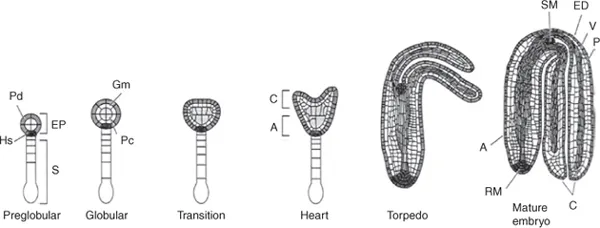

In the Poaceae (monocot), after the first division of the zygote, the basal cell does not divide but forms the terminal cell of the suspensor (Black et al., 2006). The other few suspensor cells and the embryo are produced from the axial cell. After further divisions a globular-shaped embryo is formed (Fig. 1.3). It elongates to a club-like shape with radial symmetry and then becomes bilaterally symmetrical through differentiation of the absorptive scutellum and coleoptile, which covers the first foliage leaf. During the coleoptile stage of development the embryo axis and suspensor are established. Later, during the leaf stage, the shoot and root meristems are defined and leaf primordia differentiate. The embryonic cells cease to divide during maturation, the embryo desiccates and becomes quiescent. Mature graminaceous embryos also contain a specialized thin tissue, the coleorhiza, which covers the radicle.

Fig. 1.3. Stages of development of a monocot embryo, such as in rice. (a) The fertilized egg cell (zygote) undergoes (b) mitosis to form an axial (A) and a basal (B) cell. (c) A multicellular proembryo is produced from the former, and then (d) an early coleoptile (Cp) stage. Further cell divisions result in (e) a late coleoptile stage when the shoot meristem (Sm) is visible. (f) By the first leaf (1st) stage other tissues are differentiated including the scutellum and the radicle, and by (g) the second leaf (2nd) stage differentiation is m...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Overview of Seed Development, Anatomy and Morphology

- 2 Fruits and Frugivory

- 3 The Ecology of Seed Dispersal

- 4 Seed Predators and Plant Population Dynamics

- 5 Light-mediated Germination

- 6 The Chemical Environment in the Soil Seed Bank

- 7 Seed Dormancy

- 8 The Chemical Ecology of Seed Persistence in Soil Seed Banks

- 9 Effects of Climate Change on Regeneration by Seeds

- 10 The Functional Role of the Soil Seed Bank in Agricultural Ecosystems

- 11 The Functional Role of Soil Seed Banks in Natural Communities

- Index

- Footnotes