![]()

1

Introduction

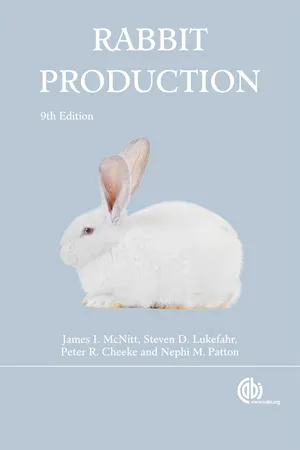

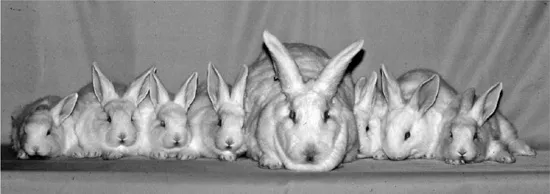

Rabbit production is developing into a significant agricultural enterprise in the United States (Fig. 1.1). It is also relatively important in several European countries, such as France, Spain, and Italy, where rabbit is regarded as a gourmet meat, and is expanding is several other countries around the world. In China, the Angora rabbit is raised for its wool which is exported to other countries for production of high quality luxury garments. Rabbit pelts are used in making fur coats and toys. In addition to being raised commercially for meat, wool, and fur, rabbits are also produced in large numbers for laboratory use. They are particularly useful in certain types of medical research. Many people in the United States raise rabbits for show or exhibition purposes and enjoy the challenge of breeding animals that possess traits that best exemplify the standards of a particular breed. Others keep rabbits simply as pets. Whatever one’s motivation for keeping rabbits, information on nutrition, diseases, breeding, and management is useful for attaining an end product of healthy, well-nourished, productive animals.

Fig. 1.1. A productive doe and her litter. Because of their high reproductive capacity and high growth rate, rabbits are among the most productive of domestic livestock. (Courtesy of P.R. Cheeke)

History, Taxonomy, and Domestication of the Rabbit

The origin and evolution of rabbits is difficult to trace, because rabbit bones are small and fragile and often are destroyed or rearranged by predators. Fossil records trace the order Lagomorpha back about 45 million years to the late Eocene period. The leporids (rabbits and hares) appear to have originated in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and southern France.

The modern lagomorphs consist of two families (Leporidae and Ochotonidae) with 11 genera (Table 1.1). They range from the highly successful hares and rabbits of the Lepus, Oryctolagus, and Sylvilagus genera to several endangered genera and species. The Bunolagus genus, with one species, the riverine rabbit, is restricted to Karoo floodplain vegetation. Other rare and endangered lagomorphs include the Sumatran hare (Nesolagus netscheri) in Indonesia, the Amami rabbit (Pentalagus furnessi) in Japan, and the volcano rabbit (Romerolagus diazi) in Mexico. Further information on rabbit taxonomy can be obtained from the internet at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leporidae.

Table 1.1. The modern lagomorphs.

| No. of Modern Species | Present Natural Geographical Distribution | Examples |

Family Leporidae | | | |

Genera: | | | |

Sylvilagus | 17 | North America, South America | Brush rabbit, swamp rabbit, cottontail |

Oryctolagus | 1 | Europe, North Africa | European wild rabbit, all domestic species |

Caprolagus | 1 | India | Hispid rabbit (endangered) |

Bunolagus | 1 | South Africa | Riverine rabbit |

Poelagus | 1 | Central Africa | Bunyoro rabbit |

Pronolagus | 2 | Southern Africa | Red rock hare (actually a rabbit) |

Pentalagus | 1 | Amami Islands (Japan) | Amami rabbit (endangered) |

Romerolagus | 1 | Mexico | Volcano rabbit (endangered) |

Nesolagus | 1 | Sumatra (Indonesia) | Sumatran rabbit, Annamite rabbit |

Brachylagus | 1 | North America | Pygmy rabbit |

Lepus | 32 | Eurasia, Africa, North America | Jack rabbit, snowshoe hare, European hare |

Family Ochotonidae | | | |

Genus: | | | |

Ochotona | 14 | Western North America, Asia | Pika |

All breeds of domestic rabbits are descendants of the European wild rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus . Rabbits were originally classified as rodents but are now placed in a separate order, Lagomorpha, primarily because they have two more incisor teeth than rodents (six instead of four). The lagomorphs are divided into two major families: (1) pikas and (2) rabbits and hares.

Pikas, or rock rabbits, are common inhabitants of mountainous areas in North America and Asia (Fig. 1.2). In contrast to other lagomorphs, they are highly vocal, having a loud call or whistle. Pikas inhabit rocky areas of talus or piles of broken rock. They collect grass and other vegetation, which they cut and then allow to cure into hay in the sun. The hay is stored in piles in the rock crevices, to be used for winter feed. Pikas differ from rabbits in a number of fairly obvious characteristics, besides their whistling and calling. Both sexes lack the typical external sex organs of other animals and instead have a cloaca into which the fecal, urinary, and reproductive tract discharges are made.

Fig. 1.2. A pika or rock rabbit. Pikas, along with rabbits and hares, are members of the order Lagomorpha. (Courtesy of Justin Johnsen, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 unported license)

They have much less developed hind legs than rabbits and hares and resemble rodents in their appearance. Pikas are commonly seen or heard in high mountain areas, where they are often observed perched on rocks. A shrill whistle is used as an alarm signal. Unlike rabbits and hares, which are nocturnal, pikas, are most active by day.

Hares differ from rabbits in that they are born fully haired, with their eyes open, and can run within a few minutes of birth (Fig. 1.3). They are born in the open without a well-defined nest. They have long legs and take long leaps or bounds when running. Hares have long ears and are wary and alert. They can detect enemies at considerable distances and depend on their speed and endurance for escape. Hares are in the genus Lepus (e.g., Lepus europaeus -European hare; Lepus californicus -black-tailed jack rabbit). Some of the more common hares in North America are the jack rabbits of the western United States and Canada and of northern Mexico. Jack rabbits can become serious agricultural pests, causing great damage to crops and rangeland. In the past, rabbit drives were used to control them, whereas pesticide baits are now employed. The Arctic hare is found in northern Canada and in Alaska, Greenland, and Asia. The snow-shoe hare is found in most of Canada and the northern continental United States. Both the Arctic and snowshoe hares have different coat colors in summer and winter, being brown in summer and white in winter. The populations of snowshoe hares in northern areas fluctuate on about a 10- year cycle. Populations of their predators, such as the snowy owl and Canada lynx, fluctuate in a similar manner. The European hare is an important species for hunting in Europe. During the breeding season, European hares engage in courtship rituals involving dashing about wildly and leaping into the air, thus accounting for the expression “mad as a March hare.” High blood levels of the male hormone testosterone occur during the period of “March madness.”

Fig. 1.3. A jack rabbit. Jack rabbits are actually hares, close relatives of rabbits. (Courtesy of B.J. Verts)

The two main genera of rabbits are the true rabbits (Oryctolagus) and the cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus) . Oryctolagus encompasses the wild European rabbit and its domesticated descendants, which include all the breeds of domestic rabbits. Sylvilagus includes a number of North American cottontails, such as the Eastern, Desert, Brush, Marsh, and Swamp cottontail rabbits.

Cottontails and domestic rabbits cannot be crossed. Laboratory investigations have shown that sperm and eggs of the two genera will fertilize, but the developing embryos die in a few hours, after about four cell divisions. The same is true for crosses of hares and rabbits. The lack of viability of the hybrid embryos is because of differences in chromosome numbers among the genera. There are 22 chromosome pairs in Oryctolagus, 21 in Sylvilagus, and 24 in Lepus.

The story of the domestication of rabbits is shrouded in mystery. It is believed that the original site of domestication was the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal and the south of France). The first recorded rabbit husbandry was in early Roman times, when rabbits were kept in leporaria, or walled rabbit gardens. Rabbits reproduced in these enclosures and were captured and killed for food. In the Middle Ages, sailing vessels distributed rabbits on islands in various sea lanes, to be used as a source of food by sailors. Wherever these releases were made, the rabbits increased greatly in number at the expense of the indigenous animals. As exploration of the world increased, the European wild rabbit was further distributed by sailors. In 1859, a few rabbits were released in Victoria, Australia and, in 30 years, gave rise to several million rabbits. Other releases of a few rabbits in Australia also gave rise to millions of rabbits in the areas of release. The wild rabbit became a serious pest in Australia and New Zealand because of the favorable environment, abundant feed, and absence of predators. The European wild rabbit, although released in North America, was never able to gain a foothold and does not exist on the continent in significant numbers. A feral population of Oryctolagus has developed on the San Juan Islands off the coast of the state of Washington.

In the Middle Ages, rabbits were kept in rock enclosures in England and Western Europe. True domestication probably began in the sixteenth century in monasteries. By 1700, seven distinct colors and patterns had been selected: non-agouti solid color, brown, albino, dilute (blue), yellow, silver, and Dutch spotting. By 1850, two new colors and the Angora-type hair had been developed. Between 1850 and the present, the remaining colors and fur types have been developed and selected.

Potential of the Rabbit for Meat and Fur Production

The domestic rabbit has the potential to become one of the world’s major livestock species. In the future, as the human population exerts increasing pressure on the world’s food resources, it is likely that rabbits will assume an increasingly important role as a source of food. However, this does not imply that rabbits will have to be raised mostly on large commercial farms; rather, it is likely that many more people than at present will raise them in small numbers in their backyards. Rabbits also possess various attributes that are advantageous in comparison to other livestock. Rabbits can be successfully raised on diets that are low in grain and high in roughage. Recent research has demonstrated that normal growth and reproductive performance can be achieved on diets containing no grain at all. As competition between humans and livestock for grains intensifies, rabbits will have a competitive advantage over swine and poultry, since these animals cannot be raised on high roughage diets or diets that don’t contain grain. Rabbits convert forage into meat more efficiently than ruminant animals, such as cattle and sheep. From a given amount of alfalfa, rabbits can produce about five times as much meat as beef cattle. All these attributes are especially relevant today with rising feed and fuel costs.

The ability of rabbits to efficiently convert forage into meat will be of special significance in developing countries, where population pressures and food shortages are greatest. In many cases, there is abundant local vegetation that cannot be consumed directly by people but that can be fed to rabbits. A few does can be kept by village...