![]()

PART I

About the Feather and Its Development

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Feather, a Triumph of Natural Engineering and Multifunctionality

Theagarten Lingham-Soliar*

Nelson Mandela University, South Campus, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Structures in nature have evolved over millions of years and, unlike in engineering, are multifunctional. For example, an airplane wing may perform only a single function: lift. This is unlike the bird wing which, besides also producing power, has an ability to detect local updraught information along the entire surface of the wing such as changes in the distribution of pressure that are vital to soaring and energy saving. This chapter demonstrates how multifunctionality of the feather has enabled vital aspects of bird life. Three of these, involving flight, protection and temperature control, are discussed.

The feather is a structure central to bird flight and the rachis is the central structure of the feather. Syncytial barbule fibres in the rachis are long continuous strands with intermittent hooked nodes, which contribute with the matrix to form the most effective bonding mechanisms known in nature. The unique micro-structure of feathers that has enabled flight has also contributed to a tough outer integument that protects the bird against predators and the environment. Feathers are organized into tracts or pterylae with spaces, the apteria. This system of feather arrangement enables a dense layering of the feathers for mechanical protection without impeding movement. The apteria also help to reduce the total weight of the feathering, which is important for flight.

The precise design of the barbule with nodes and hooks is fundamental to the process of thermoregulation in down feathers. The embryonic down feathers of chicks form individual ‘clumps’ of more or less circular masses that have a tree-like, highly organized self-similar structure, which is crucial to its thermal properties. Each tree-like assemblage comprises a barb and branching barbules, described as primary and secondary structures, attached to the skin by a quill. The whole structure creates a ‘fluffiness’ that helps to trap the warm air.

INTRODUCTION

When vertebrates moved on to land hundreds of millions of years ago, one of the major changes involved a fundamental development of the skin with – for the first time – a distinctive epidermis and the development of a complete body covering of scales. The epidermis was capable of providing mechanical protection, preventing desiccation and providing ultraviolet protection, which together with the dermis provided a double layer of protection. The momentous development was in the composition of the scales of an entirely new material: b-keratin, which is extremely tough and stable and, critically, extremely lightweight. The properties of b-keratin would be applied to the development of the feather and it is probably safe to say that bird flight would not have evolved were it not for this material (Lingham-Soliar, 2014b). Most aspects of bird life are inextricably linked to feather structure and evolution. This chapter looks at the role the feather has played in three vital and fundamental aspects of bird life: flight, protection and thermoregulation.

FEATHERS AND FLIGHT

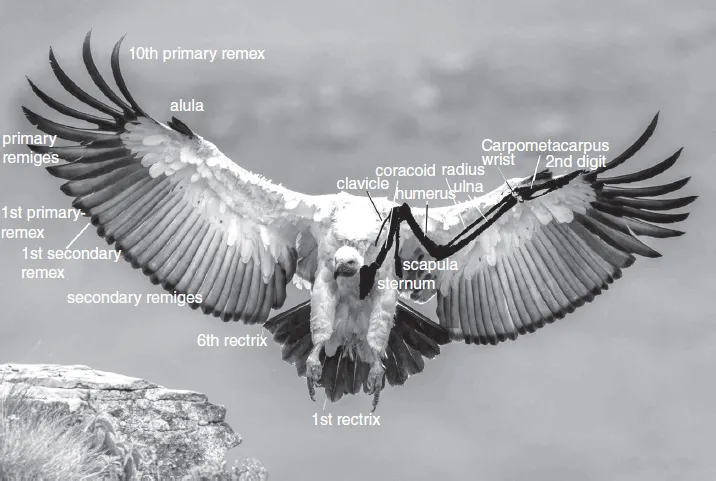

The arrangement of wing feathers (remiges) and tail feathers (rectrices) is shown for a bird of prey (Fig. 1.1).

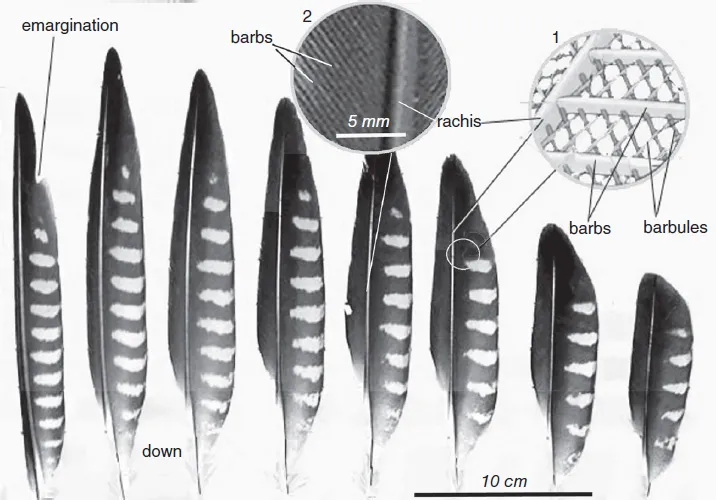

The longest wing feathers are the primaries, which extend from the carpal (‘wrist’) joint towards the wing tip (Fig. 1.2). They are generally numbered from the carpal joint to the end of the extended wing (descendent system) (LinghamSoliar, 2015), although in some literature the primary feathers are numbered from the wing tip to the carpal joint (ascendant system).

Fig. 1.1. Location and nomenclature of wing and tail feathers in the Cape vulture, Gyps caprotheres. The left wing shows the internal skeletal structure. Modified from Lingham-Soliar (2015).

The shorter secondary flight feathers grow from the ulna (forewing bone); these are always numbered from the carpal joint inwards towards the body. The innermost secondaries are also referred to as tertials or tertiaries, especially for passerine birds such as the raven (Proctor and Lynch, 1993). The primaries and secondaries together form the lifting surface of the wing.

The typical feather consists of a central shaft (rachis), applied to the portion of the axis of the feather that in life protrudes from the skin, and the lower part, which penetrates the skin and provides attachment and is termed the calamus or quill. Arising from the rachis are serial paired branches (barbs) extending out from the shaft at an angle and lying parallel to each other (Lingham-Soliar, 2017). The barbs possess further branches: the barbules. The barbules of adjacent barbs are attached to one another by hooks. The entire system comprising barbs and barbules forms a vane or web on either side of the rachis, providing the lifting surfaces of the wing and tail feathers. This construction ensures the elasticity of the feather web as well as the capacity of the barbs to re-establish linkage if the continuity of the web is interrupted (Fig. 1.2).

Feathers arise from the integument or skin of birds. The skin is fundamentally adapted to their life as active homeothermic (stable independent body temperature) animals. It is generally thin in areas covered by feathers and thick in bare areas. Its germinative layer is like that in reptiles, but the corneous layer is much thinner in birds than in reptiles (Stettenheim, 2000), where in the latter it aids in protection.

Fig. 1.2. Flight feathers in a juvenile peregrine falcon, Falco peregrinus (primaries 2 and 4 missing). The rachis is visible. Inset 1: diagrammatic view of rachis, barbs and barbules. Note that the sizes of the elements are not to scale. Inset 2: enlarged view showing relative sizes of rachis and barbs. Modified from Lingham-Soliar (2015).

Feathers are constructed of compact b-keratin, the keratin of reptiles and birds (sauropsids), a light rigid material (Fraser and Parry, 2008, 2011). The demands on the feather connected with flight are extraordinary: its qualities are almost paradoxical, having to be exceedingly light (or the bird would never leave the ground) and at the same time exceedingly tough to cope with the stresses of flight in which accelerations may reach extremely high g-forces (Clark, 2009). It is beyond the scope of this review to discuss the aerodynamics of bird flight but the reader may be interested in a review on flight in animals and some of the physics involved (Lingham-Soliar, 2015).

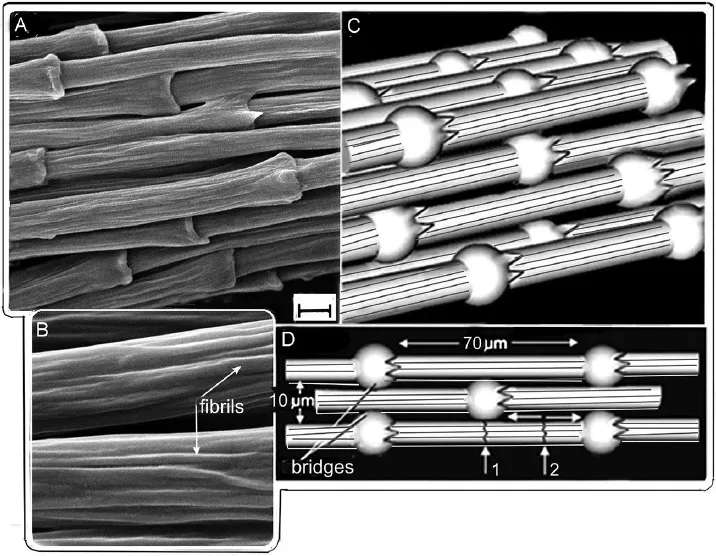

Recent research efforts using the microbes (fungus genus Alternaria) that normally parasitize bird feathers in the wild (Lingham-Soliar et al., 2010) have now made it possible to attempt to answer the question that Gordon (1978) had posed many years ago. The unique assemblage of syncytial barbule fibres (SBFs) in the cortex of the rachis and barbs enabled a microstructure with a high ‘work of fracture’. The model showed (Lingham-Soliar, 2014a) that rather than the traditional brick-and-mortar arrangement considered previously (Lingham-Soliar et al., 2010), the architecture was more comparable with the ‘brick-bridge-mortar’ structure proposed for nacre (Song and Bai, 2001; Katti and Katti, 2006).

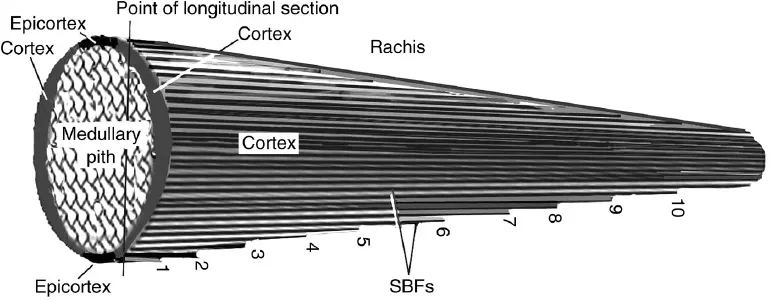

We know today that the fundamental structural component of the feather rachis is a system of continuous b-keratin SBFs that extend from the base of the rachis in a proximo-distal direction to its tip. Herein lies a problem if birds are to fly. The rachis may be described as a generalized cone of rapidly diminishing volume (Fig. 1.3).

Thus the volume of the cortex available for SBFs will decrease proximo-distally. Consequently, hundreds of SBFs in the rachidial cortex would theoretically have to be terminated before reaching the rachis tip – creating potentially thousands of inherently fatal crack-like defects. These defects of free ends or notches at numerous points of the cortex along the length of the rachis would locally concentrate the stress at each so- called notch (Lingham-Soliar, 2017). Simple mechanics shows that sudden failure in a material begins at a notch or crack that locally concentrates the stress. This is analogous to the scissor- snip a tailor makes before tearing a piece of fabric. Griffith (1921) showed that, according to thermodynamic principles, the magnitude of the stress concentration at a crack tip is dependent on the crack length, i.e. that the strain energy released in the area around the crack length is available for propagating the crack (similar to the scissor- snip). Given that there are thousands of SBFs in the feather, it is clear that there is a dangerous potential of numerous (hundreds of) self- perpetuating cracks in the feather cortex. The rachis of each feather would fail during the stresses of flight, resulting in a ‘crash- and- burn’ catastrophe. Clearly birds had solved the problem. The subject of the study (Lingham-Soliar, 2017) was: how? Briefly, for the first time we discovered that the SBFs of the barbs arise from well within the rachis, giving a stability hitherto unknown. This has not only solved the problem of the Griffith cracks but once again demonstrates the multifunctionality of bird structure in a unique tissue structure of the rachis that profoundly enhances the combined strength of the rachis and barbs.

Fig. 1.3. Feather rachis as a cone. Diagrammatic view of the rachis as a tapering cone showing potential terminations of SBFs (numbered 1–10, along the edge for illustrative convenience) because of the linear decrease in cortex thickness in the proximo-distal direction. Modified from Lingham-Soliar (2017).

FEATHERS AND PROTECTION

Two aspects of protection will be considered. The first is defence against predation and the second is protection from the environment.

It may be a chicken-and-egg question, i.e. which came first: protection or flight? The author’s own view is that flight was the ultimate honing of a structure, the feather, which was evolving over 150 million years plus, from a basic component akin to the syncytial barbule filaments (Lingham-Soliar et al., 2010). The syncytial barbule filaments were already equipped for a highly important function, thermoregulation (see below), which would later be vital to all aspects of bird life.

Even predatory birds such as hawks that prey on other birds in the air are aware of the ineffectiveness of their sharp talons and beak against the prey’s protective densely feathered coat. Instead the hawk kills by diving and striking the bird in the back with its outstretched feet so as to impart a violent acceleration to the bird as a whole, which has the effect of breaking its neck (Gordon, 1978).

Bird feathers play another role during predation attempts that has evolved as a means of escape: birds often lose feathers because predators are more likely to grab feathers on the rump and the back than on the ventral side of an escaping bird. It is better that a predator (e.g. a cat) ends up with a mouthful of feathers than a mouthful of bird. Møller et al. (2006) predicted that ‘the former feathers would have evolved to be relatively loosely attached as an antipredator strategy in species that frequently die from predation’.

The second part of this section considers how the feather has enabled birds to invade every form of environment on the planet. Many birds fly constantly in and out of trees and hedges and other obstacles, often using such cover as a refuge from their enemies. The unique structure of the feather vanes enables birds to get away with local scrapes and abrasions compared with the membranous wings of other active fliers, past and present.

The flat surface or vane of the pennaceous feather is deceptive and gives the impression of a continuous membrane. It was mentioned above that the barbs and barbules are central to the flight surface or venation of the pennaceous feather structure. Regal (1975) described how the interlocking barbules from adjacent barbs lock parts of the feather into a single tough, flat surface. The barbules of adjacent barbs are able to interlock essentially because those along the distal edge (edge away from the body) of a barb bear tiny hooklets that engage the unhooked (flange-bearing) barbules branching from the proximal edge (edge towards the body) of the adjacent barb. This is seen graphically in a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a barb (close to the rachis) in the peregrine falcon, Falco peregrinus (Fig. 1.4).

The system works like opposite pieces of Velcro and is as easily separated and reconnected. Thus, when forces are applied to the surface of this vane, part of the force will be absorbed in elastic deformation of the complex system, or if the force is too great the counterpart barbules will separate and either reattach automatically, or if not, when the bird preens or nibbles its feathers, i.e. runs its beak along the separated barbules to reconnect them to the interlocked state. To put it simply, feathers avoid tears by having a structure that actually enables tearing but with the all- important differences: it occurs as part of a precise design and it is self- repairing or with a little attention from the bird.

Fig. 1.4. Mechanical structure of syncytial barbule cells (fibres). (A) Syncytial barbule cells in the cortex of the feather rachis showing nodes. (B) Detail of the syncytial barbule cells comprising fibrils. (C) Diagrammatic representation of fibre bundling (syncytial barbules) in three dimensions. (D) Diagrammatic brick-bridge-mortar structure between syncytial barbules and polymer matrix demonstrating crack-stopping mechanisms (see text). Scale bar 5 μm. After Lingham-Soliar (2014c), courtesy of Springer, Heidelberg.

This remarkable flight surface of feathers together with the formation into thick layers has enabled birds to live in densely structured habitats where even the loss of a reasonable number of feathers is a small price to pay for their ecological versatility. Besides, birds have one more ‘ace up their sleeve’. When feathers may become too ragged for repair and inefficient, they are simply replaced. Most bird species moult their entire plumage at least once a ye...