eBook - ePub

Invasion Biology

Hypotheses and Evidence

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Invasion biology has many hypotheses, but it is largely unknown whether they are backed up by empirical evidence. This book fills that gap by (a) further developing a tool for assessing research hypotheses and (b) applying it to a number of invasion hypotheses, using the hierarchy-of-hypotheses (HoH) approach. Part 1, an overview chapter of invasion biology will be followed by an introduction to the HoH approach and short chapters of science theorists and philosophers that comment on the approach. Part 2 outlines the 30 invasion hypotheses and their interrelationships. Part 3 suggests future directions of invasion research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Invasion Biology by Jonathan Jeschke, Tina Heger, Jonathan M. Jeschke,Tina Heger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction to Invasion Biology and the Hierarchy-of-hypotheses Approach

1

Invasion Biology: Searching for Predictions and Prevention, and Avoiding Lost Causes

1School of Biological Sciences and the Environment Institute, The University of Adelaide, Australia; 2Landcare Research New Zealand, Lincoln, New Zealand; 3Department of Ecology, Evolution and Natural Resources, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, USA; 4Department of Genetics, Evolution & Environment, Centre for Biodiversity & Environment Research, UCL, UK; 5Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, UK

Abstract

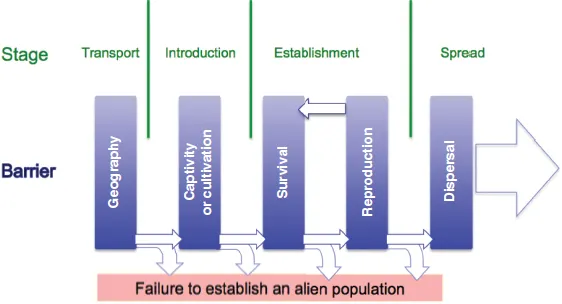

The introduction and establishment of alien species is one of the many profound influences of ongoing anthropogenic global environmental change. Invasion biology has emerged as the interdisciplinary study of the patterns, processes and consequences of the redistribution of biodiversity across all environments and spatio-temporal scales. The modern discipline hinges on the knowledge that biological invasions cannot be defined and studied solely by their final outcome of establishing alien species but rather as a sequential series of stages, or barriers, that all alien species transit: the ‘invasion pathway’. Some of the most important influences for a species transiting these sequential stages (i.e. transport, introduction, establishment and spread) are event-level effects, which vary independently of species and location, such as the number of individuals released in any given location (propagule pressure). The number of studies of biological invasions has increased exponentially over the past two decades, and we now have a significant body of research on different aspects of the invasion process. In particular, the hierarchical nature of the invasion pathway has lent itself strongly to modern statistical methods in hierarchical modelling. Now, the science behind invasive species management must continue to develop innovative ways of using this accumulated knowledge for delivering actionable management procedures.

Introduction

Human populations have had a profound impact on all natural environments and the biological diversity they contain and support (Magurran, 2016). Alongside massive population growth, the continued rapid urbanization and globalization of human technology, transport and trade are all increasing this impact. In response, new scientific disciplines have emerged to evaluate the patterns, processes and consequences of human-induced global environmental change (Costanza et al., 2007). One such discipline is invasion biology: the study of species (populations and individuals) that have been redistributed outside their native geographic ranges as a result of human-mediated translocation (hereafter termed ‘alien species’). Alien species can be transported to their new recipient locations intentionally through deliberate introduction or accidentally through unintentional ‘stowaway’ and/or escape (Hulme, 2009).

Throughout human history the trans-location of species has greatly benefited human welfare and livelihood. Today, there are many tens-of-thousands of alien species that are used in foodstuffs (farmed, cultivated and harvested), as commercial materials (timber, packaging, clothing, derivatives and pharmaceuticals), and as ornamentals (garden plants, pets and commensal species). In rare cases (and not without controversy) alien species have also been promoted to assist species conservation (Schlaepfer et al., 2011) and for responding to biodiversity loss through anthropogenic climate change (i.e. via assisted translocation; McLachlan et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the ledger of the effects of alien species also has a long (arguably longer) debit column. Invasive alien species (IAS) act as a massive drain on global resources (Early et al., 2016). Recent assessments suggest that they cost the economy of the UK at least £1.7 billion per annum (Williams et al., 2010) and that of the EU at least €12.5 billion per annum (pa) and probably substantially more. Estimates of economic costs for other regions are similarly high (Pimentel et al., 2000). These economic debits stem from the loss of productivity in agriculture, aquaculture and forestry; mitigation and control costs associated with new building construction, energy utilities and transportation infrastructure; and the costs of surveillance, quarantine and eradication efforts designed to prevent known invasive alien species’ establishment in new regions (Kettunen et al., 2008). Alien species are also one of the major drivers of biodiversity loss worldwide. IAS have contributed to the extinction of more plants and animals since 1500 ad than any process other than habitat loss (Bellard et al., 2016). The widespread establishment of the same sets of alien species around the world erodes evolutionarily distinct communities (floras and faunas) by the process of biotic homogenization (Lockwood and McKinney, 2001). The ongoing establishment of new alien species, from almost all major taxa (Seebens et al., 2017), suggests that society is facing increasing economic and ecological costs from IAS in the coming decades (Essl et al., 2011).

The great variety of alien species, the widespread locations in which they have been released and become invasive pests, and the range of negative impacts arising from these pests has spawned a major research effort designed to understand (i.e. quantify and clarify) the invasion process, and provide the robust evidence-based activities needed to control and mitigate their impacts (Lockwood et al., 2013).

The Invasion Pathway

The genesis of invasion biology as a scientific discipline is debatable but is often argued to have started with the publication of Charles Elton’s book The Ecology of Invasions of Animals and Plants (Elton, 1958). The field nevertheless languished for a quarter of a century or so after this publication, surviving mostly within the applied work of entomologists, rangeland ecologists, weed scientists and wildlife biologists (Baker, 1974; Davis, 2006). This situation began to change when the Scientific Committee on Problems in the Environment (SCOPE) published a series of books and articles on the subject in the early 1980s (Drake et al., 1989; Davis, 2006). The SCOPE participants identified three questions for invasion biology to answer:

1. What factors determine whether a species becomes an invader or not?

2. What site properties determine whether an ecological system will resist or be prone to invasions?

3. How should management systems be developed to best advantage given the knowledge gained from studying questions 1 and 2?

Although the SCOPE programme led to many national initiatives and influential edited volumes (Simberloff, 2011), the first few decades of research into biological invasions following SCOPE were characterized by a failure to make significant progress in addressing these questions in either an explanatory or a predictive manner (Williamson, 1993, 1999).

This scientific drought ended with the widespread recognition that biological invasions should not be defined and studied solely by their final outcome of producing alien species, but rather as a sequential series of stages, or barriers, that alien species transit (Williamson, 1993). These stages – commonly categorized as transport, introduction, establishment and spread (Fig. 1.1) – constitute the invasion pathway (also known as the invasion process). Only a (native) species that successfully overcomes all of the biogeographical, social, demographic, environmental and dispersal barriers, throughout the invasion stages, will become an invasive alien species (Blackburn et al., 2011). These stages differ in the nature of the barriers imposed, and therefore the mechanisms required to overcome them. Notably, each stage generates a different set of hypotheses for how a species might transition through it (Kolar and Lodge, 2001). Partitioning the process of invasion into these stages required the testing of ideas about which species succeed at each stage in the process and which fail.

Transport

Changes in the mode and frequency by which species are transported have greatly affected temporal patterns in the sources and subsequent distribution of alien species. Early human transportation by foot, horse and sailing ship have been replaced by high-speed – and high-volume – rail, truck, ship and plane transport (Essl et al., 2015). The networks these transportation vectors travel have themselves expanded exponentially over the past century, making the species native to newly ‘opened’ regions subject to becoming transported out as aliens and making the regions themselves subject to becoming invaded (Seebens et al., 2015). The technological advancement of transportation and the globalization of trade has thus resulted in a massive expansion of the range of taxa moved by transport vectors and the speed with which these species are moved from their origin to their recipient locations (Ruiz and Carlton, 2003; Essl et al., 2015). Commodities such as fresh produce (e.g. fruit, vegetables and flowers), pets (e.g. turtles, scorpions and groupers), and ornamentals (e.g. aquatic plants, marine algae and live coral) can now be sent from nearly anywhere to nearly anywhere else in the world in less than 24 hours. Along with these commodities come their transmissible pests and diseases, and the smaller species that stowaway either on the commodity itself or in its packaging. It is clear when analysing different periods of invasion biology that different taxa and regions predominate, and that these temporal patterns strongly reflect changes and advances in global trade (Dyer et al., 2017). Recognition of the dynamic and expansive mechanisms of alien species transport forced invasion biologists to develop research programmes centred on the locations and types of species most likely to be entrained, and the causes and consequences of transport and vector dynamics (e.g. Essl et al., 2015; Turbelin et al., 2017).

Fig. 1.1. A depiction of the sequential series of stages or barriers that define the invasion pathway. This framework identifies that the invasion process can be divided into a series of stages and that in each stage there are barriers that need to be overcome for a species or population to pass on to the next stage. Modified from Blackburn et al. (2011).

Introduction

Not all individuals (or species) that are transported outside of their native range are introduced (released) into the recipient (alien) range. In some cases they do not survive transportation and thus never leave the vector (e.g. ship ballast, cargo hold), and in other cases they are contained in captivity once off-loaded into the alien range (e.g. pets, ornamental plants). Although these contained species still pose a potential invasion risk (Hulme, 2011; Cassey and Hogg, 2015), they cannot establish until they are introduced into the recipient environment. The factors that determine which species make up the pool that are initially entrained in a transportation vector are poorly understood. Similarly, there is a paucity of research into the characteristics that facilitate either their survival within the vector until release or eventual release from captivity.

The introduction stage represents a critical target for the successful management of alien species, yet we lack an appropriate level of understanding of its dynamics. Transport and introduction are sometimes combined in the same stage for theoretical or practical analytical reasons (Leung et al., 2012), which might have contributed to our limited understanding of the introduction stage. It is crucial, however, that we disaggregate these two stages, because transiting from transported to introduced breaks the major containment barrier for alien species (e.g. captivity), and potentially allows establishment (Hulme, 2011; Cassey and Hogg, 2015). Despite the sparseness of research on the likelihood of introduction, the shared conclusion across transport vectors and taxa is that increasing trade volumes of a commodity increases the likelihood of an introduction (García-Díaz et al., 2017). Interestingly, this finding links well with the propagule pressure hypothesis explaining species’ success in the next stage, establishment (see also Chapter 16, this volume). Species’ traits effectively play a role in facilitating whether a species transits from transport to introduction (Wonham et al., 2001; Su et al., 2016; Vall-llosera and Cassey, 2017). Unfortunately, there remains a substantial knowledge gap regarding this aspect. The introduction of alien species is a multi-faceted process compounded by a multitude of factors including human behaviours (e.g. reasons why people release pets or dispose of unwanted ornamental plants into natural habitats) (Cohen et al., 2007; Dehnen-Schmutz et al., 2007). Accordingly, deciphering the function of different factors in determining the likelihood of introductions is a challenging task requiring a multi-disciplinary research agenda incorporating elements from the ecological, economical and social sciences.

Establishment

The majority of research effort on the invasion pathway, to date, has been focused on the factors affecting the successful establishment of alien populations. Whether or not an introduction results in a population becoming self-sustaining depends on the intersection of three broad categories of driver: species-, location- and event-level characteristics (Duncan et al., 2003). The first two of these categories echo the first two questions of the SCOPE programme above. Species-level factors include hypotheses on how life history, evolutionary history and genetic diversity influence the probability that a nascent alien population will become self-sustaining. The location-level characteristics include the myriad hypotheses on how (and if) disturbance leaves locations more likely to be invaded, and the role of inter-specific interactions in determining the fate of a recently introduced alien population (competition, predation, mutualism), among others. The event-level category reflects barriers that vary independently of species and location, such as the number of individuals released in any given location (e.g. propagule pressure; Lockwood et al., 2005; Simberloff, 2009b). The event-level category was not identified and thus not addressed within the SCOPE programme (Blackburn et al., 2015). Hypotheses for establishment success now tend to partition along the lines of these three categories or the intersection between them. For example, underlying the variability in species, events and environments is the common relationship between a species ability to survive in a new location (abiotic and biotic tolerances) and the demographic capability of the population to increase (R0; e.g. Cassey et al., 2014).

Spread

Not all established alien species spread widely across their available range but some manage to occupy vast expanses, even occasionally spreading over entire continents (Lockwood et al., 2013). Key hypotheses invoke the role of landscape-level habitat patterns, the presence and strength of inter-specific interactions, and species traits that promote dispersal and phenotypic evolution or plasticity. An interesting phenomenon at this stage relates to those species that have apparent lag periods between...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- PART I: INTRODUCTION TO INVASION BIOLOGY AND THE HIERARCHY-OF-HYPOTHESES APPROACH

- PART II: HYPOTHESIS NETWORK AND 12 FOCAL HYPOTHESES

- PART III: SYNTHESIS AND OUTLOOK

- Index

- Back Cover