eBook - ePub

Virus Diseases of Tropical and Subtropical Crops

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Virus Diseases of Tropical and Subtropical Crops

About this book

This book describes interactions of plant viruses with hosts and transmission vectors in an agricultural context. Starting with an overview of virus biology, economics and management, chapters then address economically significant plant diseases of tropical and subtropical crops. For each disease, symptoms, distribution, economic impact, causative virus, taxonomy, host range, transmission, diagnostic methods and management strategies are discussed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Virus Diseases of Tropical and Subtropical Crops by Paula Tennant, Gustavo Fermin, Paula Tennant,Gustavo Fermin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias biológicas & Biología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Viruses Affecting Tropical and Subtropical Crops: Biology, Diversity, Management

1Instituto Jardín Botánico de Mérida, Faculty of Sciences, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida, Venezuela; 2Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma, USA 3Department of Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran 4Department of Life Sciences, The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, Jamaica

*E-mail: [email protected]

1.1 Introduction

Viruses are the most abundant biological entities throughout marine and terrestrial ecosystems. They interact with all life forms, including archaea, bacteria and eukaryotic organisms and are present in natural or agricultural ecosystems, essentially wherever life forms can be found (Roossinck, 2010). The concept of a virus challenges the way we define life, especially since the recent discoveries of viruses that possess ribosomal genes. These discoveries include the surprisingly large viruses of the Mimiviridae (Claverie and Abergel, 2012; Yutin et al., 2013), the Pandoraviruses that lack phylogenetic affinity with any known virus families (Philippe et al., 2013) and Pithovirus sibericum that was recovered from Siberian permafrost after being entombed for more than 30,000 years (Legendre et al., 2014). Apparently they co-occurred and even predated cellular forms on our planet, yet arguably they have no certain place in our current view of the tree of life (Brüssow, 2009; Koonin and Dolja, 2013; Thiel et al., 2013).

Besides their potential role in evolution, viruses have facilitated the understanding of various basic concepts and phenomena in biology (Pumplin and Voinnet, 2013; Scholthof, 2014). However, they have also long been considered as disease-causing entities and are regarded as major causes of considerable losses in food crop production. Pathogenic viruses imperil food security by decimating crop harvests as well as reducing the quality of produce, thereby lowering profitability. This is particularly so in the tropics and subtropics where there are ideal conditions throughout the year for the perpetuation of the pathogens along with their vectors. Viruses account for almost half of the emerging infectious plant diseases (Anderson et al., 2004). Moreover, technologies of DNA and RNA deep sequencing (Wu et al., 2010; Adams et al., 2012; Grimsley et al., 2012; Zhuo et al., 2013; Barba et al., 2014; Kehoe et al., 2014), as well as genomics and metagenomics (Adams et al., 2009; Kristensen et al., 2010; Roossinck et al., 2010; Rosario et al., 2012), have allowed for the discovery of new species of plant viruses – some of which have been isolated from symptomless plants (Roossinck, 2005, 2011; Kreuze et al., 2009; Wylie et al., 2013; Saqib et al., 2014). Recent investigations suggest that some viruses actually confer a range of ecological benefits upon their host plants (Mölken and Stuefer, 2011; Roossinck, 2011, 2012; Prendeville et al., 2012; MacDiarmid et al., 2013), for example, traits such as tolerance to drought (Xu et al., 2008; Palukaitis et al., 2013) and cold (Meyer, 2013; Roossinck, 2013). Studies of viruses associated with non-crop plants have only just begun, but findings so far indicate that overall very little is known about viruses infecting plants (Wren et al., 2006). It is becoming increasingly evident that the view of viruses as mere pathogens is outdated. These entities possess the potential for facilitating a variety of interactions among macroscopic life. Therefore, a lot of work is needed in terms of research dealing with the diversity, evolution and ecology of viruses to truly comprehend their rich contribution to all human endeavours, including agriculture and food security. This introductory section focuses on some of the topics that are of current interest and relevance to tropical and subtropical regions where a number of plant diseases that threaten food security are caused by viruses.

1.2 Biology: Structure, Taxonomy and Diversity

Of the ca. 2000 viruses listed in the 2013 report of the International Committee for the Taxonomy of Viruses, less than 50%, or ca. 1300, are plant viruses. Viruses, which by definition contain either a RNA or DNA genome surrounded by a protective, virus-coded protein coat (CP) are viewed as mobile genetic elements, and characterized by a long co-evolution with their host. Many plant viruses have a relatively small genome; one of the smallest among plant viruses is a nanovirus with a genome of about 1 kb while the closterovirus genome can be up to 20 kb. Despite this apparent simplicity, nearly every possible method of encoding information in nucleic acid is exploited by viruses, and their biochemistry and mechanisms of replication are more varied than those found in the bacterial, plant and animal kingdoms (MacNaughton and Lai, 2006; Koonin, 2009).

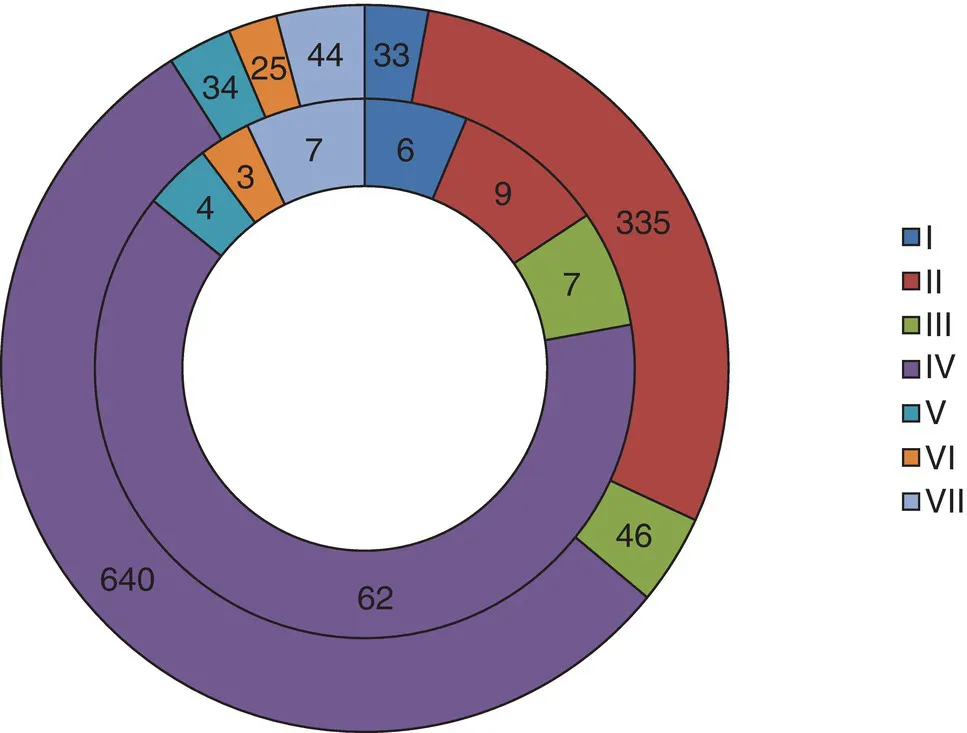

According to Baltimore (Fig. 1.1), classification of viruses comprises seven independent classes, based on the nature of the nucleic acid making up the virus particle: double-stranded (ds) DNA, single stranded (ss) DNA, dsRNA, ss (+) RNA, ss (−) RNA, ssRNA (RT) or ssDNA (RT). The entities are further categorized by the Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses into five hierarchically arranged ranks: order, family, subfamily, genus and species. The polythetic species concept (van Regenmortel, 1989) as applied to the definition of the virus species recognizes viruses as a single species if they share a broad range of characteristics while making up a replicating lineage that occupies a specific ecological niche (Kingsbury, 1985; van Regenmortel, 2003). There are also proposals for the consideration of virus architecture in the higher-order classification scheme (Abrescia et al., 2009). Arguably, the defining feature of a virus is the CP, the structure of which is restricted by stereochemical rules (almost invariably icosahedral or helical) and genetic parsimony. Hurst (2011) introduced another proposal, namely the consideration of dividing life into two domains (i.e. the cellular domain and the viral domain), and thus the adoption of a fourth domain for viruses, along with entities such as viroids and satellites. It is opined that leaving viruses out of evolutionary, ecological, physiological or conceptual studies of living entities presents an incomplete understanding of life at any level. The proposed title of this domain is Akamara, which is of Greek derivation and translates to without chamber or without void; aptly referring to the absence of a cellular structure.

Fig. 1.1. The current plant virosphere (from the term viriosphere coined by Suttle in 2005) is comprised of (pathogenic) viruses belonging to all groups under Baltimore’s classification. Group I (viruses with dsDNA genomes) include members of the family Phycodnaviridae; Group II (viruses with ssDNA genomes) those of the families Geminiviridae and Nanoviridae; Group III (viruses with dsRNA genomes) members of the families Amalgaviridae, Endornaviridae, Partitiviridae and Reoviridae; Group IV (viruses with (+) ssRNA genomes) that includes viruses from the families Alphaflexiviridae, Betaflexiviridae, Benyviridae, Bromoviridae, Closteroviridae, Luteoviridae, Potyviridae, Secoviridae, Tombusviridae, Tymoviridae, and Virgaviridae; Group V (viruses with (−) ssRNA genomes) with virus species of the families Bunyaviridae, Rhabdoviridae and Ophioviridae; Group VI (ssRNA-RT viruses with a DNA intermediate in their replication cycle) that consists of the plant virus families Pseudoviridae and Metaviridae; and finally, Group VII (dsRNA-RT viruses possessing an RNA intermediate in their replication cycle) with the members of the family Caulimoviridae. The inner circle provides the number of genera per group, while the outer circle includes the total number of species per group as of 2014. ds, double-stranded; RT, reverse transcriptase; ss, single-stranded.

1.2.1 Virus evolution and the emergence of new diseases

Viruses are recognized as the fastest evolving plant pathogens. Genetic variation allows for the emergence and selection of new, fitter virus strains, as well as shapes the dynamics surrounding plant–virus and plant–vector interactions. Genetic changes are typically accomplished by mutations, the rate of which is greatest among RNA viruses because of non-proofreading activity of their replicases (i.e. RNA-dependent RNA polymerases). Recombination, either homologous or heterologous, is another source of virus variation. Recombination in potyviruses, for instance, has been shown to be especially frequent (Chare and Holmes, 2006). In other groups, like the family Bunyaviridae, reassortment of their genome segments seems to represent the underlying source of variation (Briese et al., 2013).

Once variation is introduced, selection pressures that range from the action of host resistance genes to host shifts and environmental changes, or other mechanisms of genetic drift, contribute to changes in the genetic makeup of the virus population. Complementation between viruses in mixed infections can also lead to the maintenance of viruses with deleterious mutations, and hence increase the availability of variants that selection can act upon. Finally, current thinking suggests that genome organization, particularly in viruses showing ‘overprinting’, that is, gene overlapping, also plays a role. Gene overlapping, which allows for genome compression, can increase the deleterious effect of mutations in viruses as more than one gene is affected resulting in reduced evolutionary rates and adaptive capacity (Chirico et al., 2010; Sabath et al., 2012).

1.2.2 Wild or non-crop plants as reservoirs and targets of ‘new’ causal agents of disease

Many viruses and their respective vectors are associated with non-crop reservoirs that potentially act as bridges between crop plants. Conversely, crop viruses have the capacity to infect non-crop plants with similar probability (Vincent et al., 2014). In either scenario, the simplicity of plant virus genomes allows for quick adaptation of viruses to new hosts, and generalist viruses tend to exhibit greater potential to cause more damage than specialist viruses. While the scenario of increased virus invasion of native species is worrying and raises concern for the survival of endangered species, equally worrying is the effective ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- CABI Plant Protection Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Viruses Affecting Tropical and Subtropical Crops: Biology, Diversity, Management

- 2 Banana Bunchy Top

- 3 Wheat Dwarf

- 4 Cassava Brown Streak

- 5 Cassava Mosaic

- 6 Cucumber Mosaic

- 7 Potato Mosaic and Tuber Necrosis

- 8 Soybean Mosaic

- 9 Yam Mosaic

- 10 Sugarcane Mosaic

- 11 Papaya Ringspot

- 12 Tomato Spotted Wilt

- 13 Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl

- 14 Tristeza

- 15 Rice Tungro

- 16 Sweet Potato Virus Disease

- 17 Mealybug Wilt Disease

- 18 Viruses affecting tropical and subtropical crops: future perspectives

- Index

- Back Cover