eBook - ePub

Handbook of Microbial Bioresources, The

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Microbial Bioresources, The

About this book

Microbial technology plays an integral role in the biotechnology, bioengineering, biomedicine/biopharmaceuticals and agriculture sector. This book provides a detailed compendium of the methods, biotechnological routes, and processes used to investigate different aspects of microbial resources and applications. It covers the fundamental and applied aspects of microorganisms in the health, industry, agriculture and environmental sectors, reviewing subjects as varied and topical as pest control, health and industrial developments and animal feed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Microbial Bioresources, The by Vijai Kumar Gupta, Gauri Dutt Sharma, Maria G Tuohy, Rajeeva Gaur, Vijai Kumar Gupta,Gauri Dutt Sharma,Maria G Tuohy,Rajeeva Gaur in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze biologiche & Microbiologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Microbial Resources for Improved Crop Productivity

1Instituto de Investigaciones Químico-Biológicas, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, Mexico;

2Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico-Agropecuario No. 7, Morelia, Mexico

Abstract

The ever-increasing human population and depletion of soil, nutrient and water resources make it necessary to ensure sustainability and genetic integrity of crops via exploitation of new technologies and through better agricultural practices. Many bacterial and fungal species may contain genes for plant resistance to biotic and abiotic factors and can produce metabolites that improve both the quality and the quantity of grains, fruits, fibre and nutritional energy. To ensure that beneficial microbes are available for commercial use, development of screening methods for identifying favourable traits is necessary. Recent advances in plant molecular biology, genomics and physiology using model plants and crop species together with improvements in microbial isolation, identification and culture techniques have provided the means to accelerate and strengthen the use of microbial formulations. This chapter describes recent advances in the field of plant–microbe biotechnology, such as the use of microorganisms for enhancing plant biomass production, reinforcing immunity and conferring tolerance to abiotic stress. These approaches should provide solutions to the current major problems, such as pollution and economic costs that threaten crop productivity and ecological sustainability.

1.1 Introduction

Current agricultural practices are becoming inadequate, with an imminent decline in crop productivity because of nutrient and water shortages and reduction of fertile arable soils. In contrast the global population increases at a rate of 1.2% per year and will double from 7 × 109 to 14 × 109 in less than 60 years (Pimentel, 2012). Thus, the demand placed upon farmers to supply enough plant products is one of the greatest challenges for modern biotechnology.

Since the start of the ‘green revolution’, the use of machinery, fertilizers and agrochemicals has played an essential role in sustaining a high yield, circumventing nutrient deficiencies, and in combating pathogens and pests. However, natural conditions or inadequate management causes salinization of soils and contamination of water ecosystems; these problems in turn negatively affect the productivity and sustainability of crop plants. In this regard, the role of naturally abundant yet functionally unexplored microorganisms – mainly bacteria and fungi – is of special significance in the provision of nutrients to commercial plantations at low cost and with a lesser environmental footprint (Ortiz-Castro et al., 2009; Ortiz-Castro and López-Bucio, 2013).

Microorganisms promote plant growth directly via fixation of nitrogen (N), solubilization of phosphorus (P) and iron (Fe), production of plant growth-regulating substances such as auxins and cytokinins, or via release of quorum-sensing (QS) signals or volatiles that are recognized by roots and allow for adjustment of morphogenesis (Ortiz-Castro and López-Bucio, 2013). Moreover, microorganisms can induce resistance to pathogens through systemic acquired resistance (SAR) or induced systemic resistance (ISR), and even increase tolerance to water scarcity (Shoresh et al., 2005; Dimpka et al., 2009).

The alternative to the extensive use of fertilizers containing N, P and Fe may be the development of bacterial formulations that increase nutrient uptake or efficiency of nutrient use by crops. The microbial communities inhabiting the rhizosphere – a soil zone in close contact with plant roots – play an important role in crop improvement in different agroecosystems, but our understanding of the composition of these microbial communities and the factors that determine specific root–microbe interactions is inadequate. Worldwide, salinity is an important abiotic stress that limits crop growth and productivity. Ion imbalance and hyperosmotic stress in plants caused by high concentrations of salt often lead to oxidative stress that restricts root growth (Krasensky and Jonak, 2012). Soil salinization may be due to natural causes and is common in the hot and dry regions of the world, or it may be a consequence of inadequate management of irrigation. In this context, the use of microorganisms that stimulate root growth either by increasing the amount of root hairs or lateral root expansion offers an attractive approach to the adaptation of crops to high-salt soils (Contreras-Cornejo et al., 2014).

Combining species of microorganisms within one formulation may take advantage of multiple beneficial mechanisms. An understanding of these mechanisms is likely to lead to the development of simple and practical approaches towards sustainable plant productivity. This chapter considers the roles of microbes in phytostimulation, plant defence and plant tolerance to abiotic stress and explains how these functions improve the efficiency of use of crop resources.

1.2 Microbes Promote Plant Growth and Nutrient Uptake

Sustained agricultural productivity is unlikely to come from farmers expanding their efforts into new territories; the availability of fertile arable land is more or less fixed and unlikely to increase significantly without negative effects on biodiversity. The current goal of the industry is to grow crops within smaller, more productive areas or on soils considered marginally useful for agricultural purposes. Not all such land is marginal in the same sense; some of it may be too dry or salty or may be limited in nutrients or contain high concentrations of metals, such as aluminium, often associated with acidity. Each situation requires crop plants with different adaptive mechanisms. Thus, researchers need to develop novel strategies to make plants more productive even when growth conditions are poor. To produce more fruits or grains, simply adding more and more fertilizer each season will not help. For instance, plants react in many ways to changes in nutrient provision, including the following: (i) regulation of root nutrient uptake; (ii) changes in root architecture; and (iii) fast modulation of shoot growth. All these responses are due to the combined action of external and internal nutrient levels. Levels of macronutrients such as N, P, potassium (K) and sulfur (S) and micronutrients such as Fe (required in low concentrations but essential for photosynthesis) are sensed locally by the root system (López-Bucio et al., 2003; Amtmann and Armengaud, 2009; Hindt and Guerinot, 2012; Nacry et al., 2013). Equally important is the sensing of levels of internal nutrients or metabolites, which circulate between stems and leaves and move downwards to the root system to activate or suppress the mechanisms of nutrient uptake.

During the course of evolution, plants and microbes have developed mutually beneficial or detrimental relationships, most of which involve nutrient use efficiency. Plants interact with endophytic and mycorrhizal fungi or with bacteria that form biofilms on root and leaf surfaces or live inside plant tissues; nitrogen-fixing bacteria are housed inside root nodules, and many pathogenic organisms can initiate active infection of leaves and roots (Ortiz-Castro et al., 2009). Therefore, colonization of plants by microbes is rather the norm and not an exception. The diversity of microbes associated with roots is huge: > 33,000 prokaryotic taxa (Mendes et al., 2011). In some cases, plants have gained specific advantages from this intimate association with microbial partners, for example, an exchange of nutrients and protection from pathogens. Strong evidence exists that microorganisms affect plant fitness through direct or indirect effects on provision of nutrients. The best known microbes that help plants to deal with nutrient-poor soils are N-fixing rhizobia, which establish symbiosis with legume plants and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) that improves plant P supply in approximately 95% of land plants (Smith and Smith, 2011; Olivares et al., 2013).

An interesting example of how the concept of the use of fungi as biofertilizers has been changing with time is AMF, which live within plant roots, from which they send out filaments or hyphae that collect phosphate, a critical nutrient for their host plants. These fungi, which microbiologists first recognized ~50 years ago, are found in all soils and form symbiosis with plant roots. Years ago, when scientists applied AMF to crops, they conducted field trials mostly in North America and Europe, where plants grow well with conventional phosphate fertilizers. Adding the fungi had little effect, and in consequence, only a few farmers started using AMF for cultivation of plants. Later, it was found that the high P level in most agricultural soils negatively affects the AMF–root interaction, thereby limiting any practical applications (Gu et al., 2011).

Farming in the tropics is a different story because the soils there are often acidic. When working on acidic soils, farmers need to add large amounts of phosphates because P fertilizer combines with aluminium forming insoluble salts; therefore, P becomes unavailable for uptake by the roots. In accordance with the aim to increase yields and reduce the amounts of P used as a fertilizer, select isolates of AMF that thrive in tropical soils may improve the uptake of P by crops such as maize, sorghum and soybean grown in those regions; thus, it is important to test whether adding such fungi will improve yields (Cakmak, 2002).

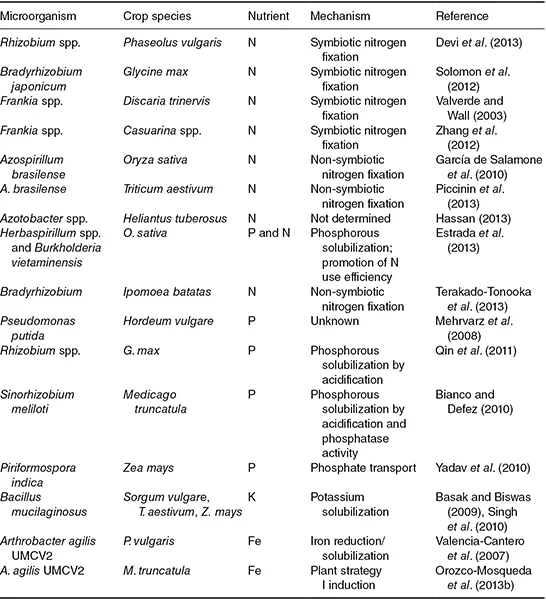

Practical studies on various crop plants have been performed in developing countries of Latin America and Africa, probably as a result of the potential for cheaper production of inoculants by small companies or research groups and the low availability of fertilizers. These studies mostly involved plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and yielded highly promising results (Bashan et al., 2014). PGPR that are used for production of inoculants include species of the genera Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Bacillus, Burkholderia, Enterobacter, Paenibacillus, Pseudomonas, Serratia and Stenotrophomonas. Genera such as these allowed for reduced application rates of chemical fertilizers in greenhouses and in field trials, for which we present just a few recent examples (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Microbial traits that enhance nutrient uptake by plants.

In a field trial that lasted 3 years, Adesemoye and associates (2008) evaluated a commercially available PGPR formulation, AMF, and their combination across two tillage systems. The inoculants promoted plant height, yield (dry mass of ears and silage) and nutrient content of grain and silage (Adesemoye et al., 2008). Subsequently, in a greenhouse study tomato plants inoculated with a mixture of PGPR strains Bacillus amyloliquefaciens IN937a and Bacillus pumilus T4 consistently provided the same yield and show the same N and P uptake at 70% of the regular fertilizer amount as do plants with full fertilizer rate without inoculants, thus saving on the amount of fertilizer used. Addition of the AMF...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Foreword

- 1 Microbial Resources for Improved Crop Productivity

- 2 The Contributions of Mycorrhizal Fungi

- 3 Trichoderma: Utilization for Agriculture Management and Biotechnology

- 4 The Role of Bacillus Bacterium in Formation of Plant Defence: Mechanism and Reaction

- 5 Biofilm Formation on Plant Surfaces by Rhizobacteria: Impact on Plant Growth and Ecological Significance

- 6 Biofilmed Biofertilizers: Application in Agroecosystems

- 7 Microbial Nanoformulation: Exploring Potential for Coherent Nano-farming

- 8 Bacillus thuringiensis: a Natural Tool in Insect Pest Control

- 9 Pleurotus as an Exclusive Eco-Friendly Modular Biotool

- 10 Use of Biotechnology in Promoting Novel Food and Agriculturally Important Microorganisms

- 11 Endophytes: an Emerging Microbial Tool for Plant Disease Management

- 12 Role of Listeria monocytogenes in Human Health: Disadvantages and Advantages

- 13 Natural Weapons against Cancer from Bacteria

- 14 Giardia and Giardiasis: an Overview of Recent Developments

- 15 Power of Bifidobacteria in Food Applications for Health Promotion

- 16 Probiotics and Dental Caries: a Recent Outlook on Conventional Therapy

- 17 Human Microbiota for Human Health

- 18 Biotechnological Production of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

- 19 Functional Enzymes for Animal Feed Applications

- 20 Microbial Xylanases: Production, Applications and Challenges

- 21 Microbial Chitinase: Production and Potential Applications

- 22 Characteristics of Microbial Inulinases: Physical and Chemical Bases of their Activity Regulation

- 23 Microbial Resources for Biopolymer Production

- 24 Microbial Metabolites in the Cosmetics Industry

- 25 Fungi of the Genus Pleurotus: Importance and Applications

- 26 Useful Microorganisms for Environmental Sustainability: Application of Heavy Metal Tolerant Consortia for Surface Water Decontamination in Natural and Artificial Wetlands

- 27 Exopolysaccharide (EPS)-producing Bacteria: an Ideal Source of Biopolymers

- 28 Microbial Process Development for Fermentation-based Biosurfactant Production

- 29 Recent Developments on Algal Biofuel Technology

- 30 Microbial Lipases: Emerging Biocatalysts

- 31 Bioremediation of Gaseous and Liquid Hydrogen Sulfide Pollutants by Microbial Oxidation

- 32 Archaea, a Useful Group for Unconventional Energy Production: Methane Production From Sugarcane Secondary Distillation Effluents Using Thermotolerant Strains

- 33 Industrial Additives Obtained Through Microbial Biotechnology: Biosurfactants and Prebiotic Carbohydrates

- 34 Industrial Additives Obtained Through Microbial Biotechnology: Bioflavours and Biocolourants

- 35 Actinomycetes in Biodiscovery: Genomic Advances and New Horizons

- 36 Molecular Strategies for the Study of the Expression of Gene Variation by Real-time PCR

- 37 Whole Genome Sequence Typing Strategies for Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli of the O157:H7 Serotype

- 38 Microbial Keratinases: Characteristics, Biotechnological Applications and Potential

- 39 Philippine Fungal Diversity: Benefits and Threats to Food Security

- Index

- Back Cover