- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Potential Invasive Pests of Agricultural Crops

About this book

Invasive arthropods cause significant damage in agricultural crops and natural environments across the globe. Potentially threatened regions need to be prepared to prevent new pests from becoming established. Therefore, information on pest identity, host range, geographical distribution, biology, tools for detection and identification are all essential to researchers and regulatory personnel. This book focuses on the most recent invasive pests of agricultural crops in temperate subtropical and tropical areas and on potential invaders, discussing their spread, biology and control.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Potential Invasive Pests of Agricultural Crops by Jorge Peña, Jorge E Peña in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Agronomy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Biology and Management of the Red Palm Weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus

Robin M. Giblin-Davis,1 Jose Romeno Faleiro,2 Josep A. Jacas,3 Jorge E. Peña4 and P.S.P.V. Vidyasagar5

1Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, University of Florida/IFAS, Davie, Florida, USA; 2Mariella, Arlem-Raia, Salcette, Goa 403 720, India; 3Universitat Jaume I, Campus del Riu Sec, Castelló de la Plana, Spain; 4Tropical Research and Education Center, University of Florida/IFAS, Homestead, Florida 33031, USA; 5King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

The red palm weevil (RPW) Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) is a palm borer native to South Asia, which has spread mainly due to the movement of cryptically infested planting material to the Middle East, Africa and the Mediterranean during the last two decades. Globally, the pest has a wide geographical distribution in diverse agro-climates and an extensive host range in Oceania, Asia, Africa and Europe. The RPW is reported to attack over 40 palm species belonging to 23 different genera worldwide. Although it was first reported as a pest of coconut (Cocos nucifera) in South Asia, it has become the major pest of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), and the Canary Island date palm (CIDP) (P. canariensis) in the Middle East and Mediterranean basin, respectively. Recent invasions suggest that it is a potential threat to P. dactylifera plantations in the Maghreb region of North Africa and a variety of palm species in the Caribbean, continental USA and southern China. Strict pre- and post-entry quarantine regulations have been put in place by some countries to prevent further spread of this highly destructive pest. Early detection of RPW-infested palms is crucial to avoid death of palms and is the key to the success of any Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy adopted to combat this pest. Because signs and symptoms of RPW infestation are only clearly visible during the later stages of attack, efforts to develop early-detection devices are being undertaken. Once infested by RPW, palms are difficult to manage and often die because of the cryptic habits of this pest. However, in the early stages of attack palms can recover after treatment with insecticides. IPM strategies, including field sanitation, agronomic practices, chemical and biological controls and the use of semiochemicals both for adult monitoring and mass trapping, have been developed and implemented in several countries. This chapter summarizes the research developed during the last century on different aspects of the RPW, including latest findings on its biology, taxonomy, geographic distribution, economic impact and management, and prevention options.

1.1 Introduction

In his seminal revision of Rhynchophorus and Dynamis, Wattanpongsiri (1966) laid out a comprehensive overview for the distribution, biology, morphology and taxonomy of these impressive palm-associated weevils. If you compare the distribution maps of Rhynchophorus species in Wattanpongsiri (1966) with what is known today, the RPW or Asian Palm Weevil (APW) Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae/Rhynchophoridae/Dryophthoridae) is the only species that has significantly expanded its range. Although not explicitly stated, a quick review of the biology and the cryptic boring behavior of these weevils in Wattanapongsiri’s tome adumbrates their invasive potential, especially if whole palms or offshoots are collected from areas where these weevils occur naturally, and moved long distances to areas where they do not occur. It turns out that the temptation to move date palms from infested areas in South and Central Asia to the Middle East and Mediterranean in the 1980s, Spain in the 1990s, France in the mid-2000s and Curaçao and Aruba in 2008 was too much for date growers and landscape developers. The weevil began to appear in new territories, aggressive treatments were attempted to fend off the invasions, epiphytotics often ensued and especially susceptible palms such as the ornamental CIDP (P. canariensis) were often available to fan the spread. Although RPW is native to Central, South and South-East Asia and is reported chiefly from C. nucifera (Wattanapongsiri, 1966), only 15% of the coconut-growing countries have reported this pest. On P. dactylifera, the spread has been rapid during the last two decades and it is now reported from 50% of the date palm-growing countries and the entire Mediterranean basin on CIDP, P. canariensis. Because R. ferrugineus has expanded its range into areas where other palm weevil species occur, such as the Americas and Africa, this has potentially exacerbated the problem of accurate identification of the Rhynchophorus species in some situations. The purpose of this chapter is to revisit what we know about Rhynchophorus ferrugineus and closely related species, with a panel of experts with differing vantage points, to gain deeper insight.

1.2 Basic Taxonomy of RPW and Relatives

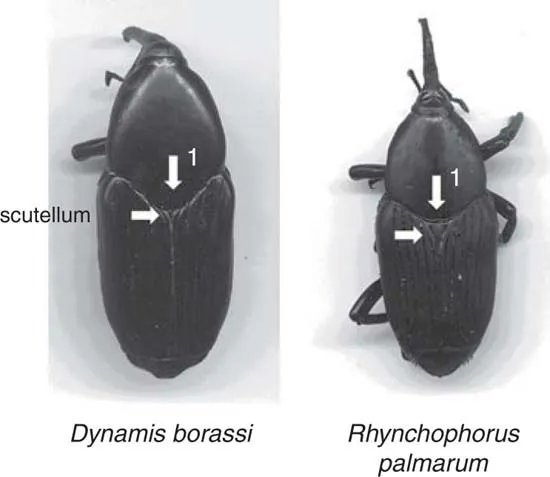

Weevil borers of palms are members of seven natural lineages within the ‘Curculionidae’ sensu lato, with the Dryophthoridae (or Dryophthorinae, depending upon the taxonomic authority used) being the most damaging to palms worldwide (Giblin-Davis, 2001). Four tribes within the Dryophthoridae are well-known from palms: the Rhynchophorini which includes the genera Rhynchophorus (mostly tropical/subtropical worldwide distribution) and Dynamis (Neotropical distribution); the Sphenophorini which includes Metamasius (Neotropical distribution), Rhabdoscelus (Asian distribution) and Temnoschoita (African distribution); the Diocalandrini which includes Diocalandra (South-East Asian distribution); and the Orthognathini which includes Rhinostomus (worldwide tropical distribution) and Mesocordylus (Neotropical distribution). Rhynchophorus and Dynamis species are most often referred to as ‘palm weevils’ and are relatively large insects, with adults being up to 5 cm long and 2 cm wide; larvae are up to 6.4 cm long and 2.5 cm wide (Giblin-Davis, 2001). Adults of Dynamis species are usually glossy black, in contrast to Rhynchophorus species which can be highly variable in coloration, ranging from all black to almost all reddish brown; with a glossy to matte, textured finish. There are nine named species of Rhynchophorus, including: R. cruentatus from Florida and the coastal southeastern USA and the Bahamas; R. palmarum from Mexico, Central and South America and the southernmost Antilles; R. ferrugineus (=R. vulneratus; see Hallet et al., 2004) originally from South-East Asia but with a recently expanded range (see above); R. phoenicis from central and southern Africa; R. quadrangulus from west-central Africa; R. bilineatus from New Guinea; R. distinctus from Borneo; R. lobatus from Indonesia; and R. ritcheri from Peru (Wattanapongsiri, 1966; Hallett et al., 2004; Thomas, 2010). R. distinctus, R. lobatus and R. ritcheri are considered rare and localized species and will not be dealt with here.

A recent pest alert was generated to help distinguish the three species occurring in the New World following the recent introduction of R. ferrugineus to Curaçao in the Caribbean (Thomas, 2010). This highlights the need to distinguish R. ferrugineus from other Rhynchophorus species where they may overlap because of expansion of the RPW range. Distinguishing R. cruentatus, R. palmarum and R. ferrugineus adults from each other is relatively easy and can be accomplished with dorsal characters of the pronotum (Thomas, 2010), but other morphological characters are necessary when trying to separate R. ferrugineus from the other common species in South-East Asia and Africa. The most reliable characters discussed by Wattanapongsiri (1966) include a combination of traits, including the pronotum, dorsal, lateral and ventral aspects of the head including the basal and distal submentum shape, sungenal suture, scutellum and mandibles (Figs. 1.1–1.8). In the following key we consider the six most common Rhynchophorus species that occur in continents or areas where RPW co-occurs or has the potential to co-occur. In essence, the first couplet used by Thomas (2010) works well to remove R. palmarum from all of the rest of the species.

Key for adults of the six most common Rhynchophorus species:

1. ‘Pronotum lobed posteriorly’; mandibles usually bidentate in lateral view; body color black (Figs. 1.1–1.3) R. palmarum**

– Pronotum flatly curved posteriorly; mandibles not bidentate in lateral view (broadly rounded or sharply tridentate); color black, red and black, or red (Fig. 1.2) 2

2. ‘Pronotum abruptly narrowed anteriorly’; giving the appearance of broad shoulders (Fig. 1.4, arrow); mandibles unidentate or broadly rounded in lateral view; males without anterio-dorsal rostral setae*** (Fig. 1.5) 3

– ‘Pronotum gradually narrowed anteriorly’ (Fig. 1.4, arrow); mandibles sharply tridentate in lateral view; males with anterio-dorsal rostral setae*** (Fig. 1.3) 4

3. a. Nasal plate present, subgenal sutures parallel-sided, wide (>25% of the head width at ventral base) (Figs. 1.5 and 1.6) R. quadrangulus

– b. Nasal plate absent, subgenal sutures tapering anteriorly, narrow (<15% of the head width at ventral base) (Figs. 1.5 and 1.6) R. cruentatus

4. a. Scutellum tapers acutely to a fine point posteriorly (Fig. 1.7) R. phoenicis

– Scutellum tapers broadly to a blunt point posteriorly (Fig. 1.7) 5

5. a. Submentum with straight subgenal sutures (Fig. 1.8) R. bilineatus

b. Submentum with concave subgenal sutures (Fig. 1.8) R. ferrugineus

***Both R. palmarum and members of the Neotropical genus Dynamis are black and have the posterior margin of the pronotum lobed posteriorly, but in Dynamis the posterior pronotal extension is about twice as deep and the scutellum is less than one-third the size (in volume) of that feature in R. palmarum (Fig. 1.1).

***Character requires presence of males. Rostral hairs can be absent in nutritionally deprived and very small males of Rhynchophorus.

1.3 General Biology, Detection and Distribution

RPW or APW, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus, is reported globally on at least 40 species of palms (i.e., Areca catechu, Arecastrum romanzoffianum, Arenga pinnata, Borassus flabellifer, Calamus merrillii, Caryota cumingii, Caryota maxima, Chamaerops humilis, Cocos nucifera, Corypha ulan, Elaeis guineensis, Livistonia decipiens, L. chinensis, Metroxylon sagu, Oncosperma horrida, O. tigillarium, Roystonia regia, P. canariensis, P. dactylifera, P. sylvestris, Sabal blackburniana, Trachycarpus fortunei and Washingtonia robusta) (Esteban-Duran et al., 1998b, Murphy and Briscoe, 1999; Malumphy and Moran, 2007; OJEU, 2008; EPPO, 2008, 2009; Dembilio et al., 2009). RPW is now known from all the continents of the world and is a key pest of coconut (Cocos nucifera) in South and South-East Asia, date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) in the Middle East and P. canariensis in Europe, and wherever they overlap. RPW, in common with all palm weevils in the genera Rhynchophorus, Dynamis, Metamasius, Rhabdoscelus and Rhinostomus, is an internal tissue borer of infested palms. If it is detected in the early stage of attack, the palm host can recover with an insecticide treatment. However, palms in the latter stages of attack exhibit extensive tissue damage in the region of the apical meristem, often harboring several overlapping generations of RPW. These palms are difficult to treat and usually die. The lethal nature of this pest, coupled with the high value of the attacked palm species, warrants early action against RPW.

Fig. 1.1 Dorsal views of diagnostic traits (i.e., the posterior pronotum edge (=vertical arrows) and relative scutellum size (=horizontal arrows) between the genera Dynamis and Rhynchophorus. (Photos: R.M. Giblin-Davis.)

Fig. 1.2 Dorsal views of the posterior pronotum edge (=vertical arrows) showing the differences between Rhynchophorus palmarum and five other species of Rhynchophorus. (Photos: R.M. Giblin-Davis.)

Palm weevils in general and RPW in particular are attracted to wounded, damaged, or dying palms, and in cases such as the CIDP, to apparently healthy palms (Hunsberger et al., 2000). Males of these weevils produce aggregation pheromones that are synergistically attractive with the kairomones produced by suitable hosts, usually early fermentation products such as ethyl esters and ethanol (Giblin-Davis et al., 1996a). Once they arrive at a palm, males and females typically seek protection from water loss by burrowing down into the petiole bases in the crown region, into fleshy wounds, or into the junction between off-shoots and the mother stem in palms such as the date palm. Like most weevils, RPW females use small mandibles at the distal tip of the distended rostrum to chew a hole into suitable host tissue before oviposition of a 2–3 mm long yellowish-colored egg. Eggs are often laid in close proximity to one another and take 2–4 days to eclose as small, first instar, legless larvae. The lower temperature threshold for the egg stage is 13.1°C and this stage has a thermal constant of 40.4 ± 2.0 DD (day degrees) (Dembilio and Jacas, 2011). In general, studies suggest that a gravid female will lay about 250 eggs (3–531) over her lifetime (which may last up to 120 days) and may require multiple inseminations to insure fertility. There are 13 larval instar stages of increasing head capsule and body size with incr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1. Biology and Management of the Red Palm Weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus

- 2. Avocado Weevils of the Genus Heilipus

- 3. Exotic Bark and Ambrosia Beetles in the USA: Potential and Current Invaders

- 4. Diabrotica speciosa: an Important Soil Pest in South America

- 5. Potential Lepidopteran Pests Associated with Avocado Fruit in Parts of the Home Range of Persea americana

- 6. Biology, Ecology and Management of the South American Tomato Pinworm, Tuta absoluta

- 7. Tecia solanivora Povolny (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), an Invasive Pest of Potatoes Solanum tuberosum L. in the Northern Andes

- 8. The Tomato Fruit Borer, Neoleucinodes elegantalis (Guenée) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), an Insect Pest of Neotropical Solanaceous Fruits

- 9. Copitarsia spp.: Biology and Risk Posed by Potentially Invasive Lepidoptera from South and Central America

- 10. Host Range of the Nettle Caterpillar Darna pallivitta (Moore) (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae) in Hawai’i

- 11. Fruit flies Anastrepha ludens (Loew), A. obliqua (Macquart) and A. grandis (Macquart) (Diptera: Tephritidae): Three Pestiferous Tropical Fruit Flies That Could Potentially Expand Their Range to Temperate Areas

- 12. Bactrocera Species that Pose a Threat to Florida: B. carambolae and B. invadens

- 13. Signature Chemicals for Detection of Citrus Infestation by Fruit Fly Larvae (Diptera: Tephritidae)

- 14. Gall Midges (Cecidomyiidae) attacking Horticultural Crops in the Caribbean Region and South America

- 15. Recent Mite Invasions in South America

- 16. Planococcus minor (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae): Bioecology, Survey and Mitigation Strategies

- 17. The Citrus Orthezia Praelongorthezia praelonga (Douglas) (Hemiptera: Ortheziidae), a Potential Invasive Species

- 18. Potential Invasive Species of Scale Insects for the USA and Caribbean Basin

- 19. Recent Adventive Scale Insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) and Whiteflies (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Florida and the Caribbean Region

- 20. Biology, Ecology and Control of the Ficus Whitefly, Singhiella simplex (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae)

- 21. Invasion of Exotic Arthropods in South America’s Biodiversity Hotspots and Agro-Production Systems

- 22. Likelihood of Dispersal of the Armored Scale, Aonidiella orientalis (Hemiptera: Diaspididae), to Avocado Trees from Infested Fruit Discarded on the Ground, and Observations on Spread by Handlers

- 23. Insect Life Cycle Modelling (ILCYM) Software – A New Tool for Regional and Global Insect Pest Risk Assessments under Current and Future Climate Change Scenarios

- Index