eBook - ePub

Biological Control of Plant-parasitic Nematodes

Soil Ecosystem Management in Sustainable Agriculture

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Biological Control of Plant-parasitic Nematodes

Soil Ecosystem Management in Sustainable Agriculture

About this book

Plant-parasitic nematodes are one of multiple causes of soil-related sub-optimal crop performance. This book integrates soil health and sustainable agriculture with nematode ecology and suppressive services provided by the soil food web to provide holistic solutions. Biological control is an important component of all nematode management programmes, and with a particular focus on integrated soil biology management, this book describes tools available to farmers to enhance the activity of natural enemies, and utilize soil biological processes to reduce losses from nematodes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Biological Control of Plant-parasitic Nematodes by Graham R. Stirling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Agronomy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section V

Natural Suppression and Inundative Biological Control

9

Suppression of Nematodes and Other Soilborne Pathogens with Organic Amendments

Soilborne pathogens are an insidious problem in all agricultural crops. Numerous fungi, bacteria, oomycetes and nematodes debilitate root systems; cause wilt, root rot and damping-off diseases; and are associated with poor growth, yield decline and replant problems. In many crop production systems, losses from soilborne diseases are the norm, and preferred crops can only be grown successfully if specific management practices (e.g. crop rotations, disease-resistant varieties, soil fumigation) are implemented to limit damage. However, there are also situations where disease severity is not as high as expected, given the prevailing environment and the level of disease in surrounding areas. Sometimes this is due to subtle variations in soil physical or chemical factors (e.g. sand or clay content, pH or nutrient status), but in other cases it is a biological phenomenon. In these situations, naturally occurring soil organisms interact in some way with the plant or pathogen and either protect the plant from disease, or minimize disease severity.

The most common form of disease suppressiveness (often referred to as ‘general’ or ‘non-specific’ suppressiveness) is discussed in this chapter. It is found in all soils and provides varying degrees of biological buffering against most soilborne pests and pathogens. Since the level of suppressive activity is broadly related to total soil microbial biomass and is enhanced by practices that conserve or enhance soil organic matter, the term ‘organic matter-mediated general suppression’ is also commonly used (Hoitink and Boehm, 1999; Stone et al., 2004). This type of suppression can be removed by sterilizing the soil, and is due to the combined effects of numerous soil organisms acting collectively through mechanisms such as parasitism, predation, competition and antibiosis.

A second form of suppression (usually known as ‘specific’ suppressiveness) is discussed in Chapter 10. Although it can also be eliminated by sterilization and various biocidal treatments, it differs from general suppressiveness in that it results from the action of a limited number of organisms. This type of suppression relies on the activity of relatively specific antagonists and can be transferred by adding small amounts of the suppressive soil to a conducive soil (Weller et al., 2002; Westphal, 2005). Since specific suppression operates against a background of general suppressiveness (Cook and Baker, 1983), the actual level of suppressiveness in a soil will depend on the combined effects of both forms of suppression.

The organic matter required to sustain the activity of the organisms responsible for general disease suppressiveness can be imported from elsewhere and added to soil as an amendment, or it can be obtained from the residues of crops grown in situ. This chapter covers the use of organic amendments to enhance suppressiveness. Issues related to the way residues are managed within a farming system to improve physical, chemical and biological fertility, thereby reducing the impact of soilborne diseases, are covered in Chapter 11. Although general suppressiveness to plant-parasitic nematodes is the main focus of this chapter, there is also a brief discussion of broad-spectrum suppressiveness to other pathogens. Nematodes are only one of many soilborne constraints to crop production, and one advantage of organic matter-mediated suppressiveness is that it provides some protection against most, if not all, members of the soilborne pest/pathogen complex.

Organic Matter-mediated Suppressiveness for Managing Soilborne Diseases

Although organic inputs from roots, crop residues and animal manures are known to play a vital role in determining a soil’s physical, chemical and biological properties (see Chapter 2), the practices employed in many modern farming systems have destroyed the link between organic matter and soil fertility. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the area of soilborne disease management. Levels of soil organic matter have declined, soils are now conducive rather than suppressive to soilborne diseases, and so natural forms of control have been replaced by soil fumigants, nematicides, fungicides and disease-resistant varieties. One possible exception is some sections of the container-based nursery industry, where compost-amended potting mixes are used to suppress root rots caused by Pythium and Phytophthora, and provide some suppression of Rhizoctonia damping-off (Hoitink and Boehm, 1999).

Organic matter-mediated suppressiveness has one main advantage over other forms of disease control: it is effective against a wide range of fungal, oomycete, bacterial and nematode pathogens that often act together to cause crop losses. Examples of its spectrum of activity are too numerous to mention here, but include suppression of Pythium in Mexican fields following the application of large quantities of organic matter over many years (Lumsden et al., 1987); the use of cover crops, organic amendments and mulches to suppress Phytophthora root rot of avocado in Australia (Broadbent and Baker, 1974; Malajczuk, 1983; You and Sivasithamparam, 1994, 1995); suppression of the same disease with Eucalyptus mulch in California (Downer et al., 2001); the management of a fungal, bacterial and nematode-induced root disease complex of potato in Canada with chicken, swine and cattle manures (Conn and Lazarovits, 1999; Lazarovits et al., 1999, 2001); the use of crop residues, animal manures and organic waste materials to reduce damage caused by plant-parasitic nematodes (reviewed by Muller and Gooch, 1982; Stirling, 1991; Akhtar and Malik, 2000; Oka, 2010; Thoden et al., 2011; McSorley, 2011b; Renčo, 2013); changes in crop rotation and tillage practices to enhance suppressiveness to potato diseases caused by Rhizoctonia, Fusarium, Helminthosporium and Phytophthora (Peters et al., 2003); and the use of fresh and composted paper waste residuals to suppress Pythium and Aphanomyces, the causes of common root rot of snap bean (Rotenberg et al., 2007a). Tables in Litterick et al. (2004), Noble and Coventry (2005), and Janvier et al. (2007) provide other examples.

Sources of organic matter for use as amendments, and their beneficial effects

The only way to maintain levels of organic carbon in agricultural soils is to continually replace the organic matter that is lost through decomposition and removal of harvested product. Crop residues, biomass from cover crops and manures produced by on-farm livestock are the most sustainable sources of organic matter, as they can be produced on-farm, eliminating the transport costs involved in importing organic matter from elsewhere. However, agriculture is an export-oriented industry, and so the nutrient cycle loop can only be closed by ensuring that nutrients that leave the farm are ultimately returned to the farm (Gliessman, 2007). Thus, there is a place in agriculture for utilizing organic wastes associated with feedlots, dairies, sugar mills and other food production and processing operations, and the sewage produced in cities and towns, as a source of nutrients and organic matter. Composting or other means of stabilization or treatment may be needed to ensure that the organic material does not pose a threat to public health, and also to eliminate weed seeds and plant pathogens, but such treatments are an essential component of a process that produces useful amendments from wastes that would otherwise be incinerated or disposed of in landfills.

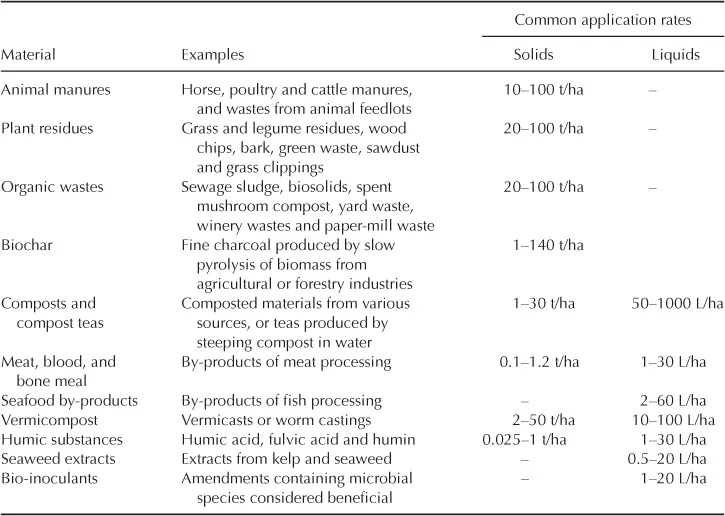

Many different organic materials are available for use as soil amendments in agriculture, and they can be subdivided into numerous categories (Table 9.1), or grouped more broadly into composts, uncomposted materials, manures, compost extracts and compost teas (Hue and Silva, 2000; Litterick et al. 2004). A list of the amendments commonly available to landholders, together with data on their macro- and micro-nutrient content, can be found in Quilty and Cattle (2011). Many of these materials are commercial products, and are marketed on the basis that they will improve soil health and increase yields. However, the benefits from some of these products are often overstated, with claims made by suppliers and manufacturers frequently based on anecdotal rather than scientific evidence.

Table 9.1. A selection of organic materials commonly available for use as soil amendments in agriculture.

Modified from Quilty and Cattle (2011).

The role organic matter in promoting the physical, chemical and biological health of soil is widely recognized, as the practice of adding manures and crop residues to soil is as old as agriculture itself. However, this does not mean that amending soil with organic matter is always beneficial, or that it is useful in all environments. Organic amendments act in many different ways, and enhanced suppression of pests and diseases is only one of many possible effects. Some of those effects are briefly discussed next, and further detail can be found in Quilty and Cattle (2011).

• A source of plant nutrients. All organic materials contain plant nutrients, and when applied to soil as an amendment, they sometimes supply enough nutrients to maintain crop yields at the levels achievable with inorganic fertilizers. However, more commonly, the rate of mineralization is insufficient to meet plant demands, and the application rates required to obtain nutritional benefits are economically prohibitive. Other amendments such as biochar have no nutrient value, and most liquid organic amendments are applied at rates that are unlikely to produce more than minor nutritional effects.

• Stimulation of plant growth. Research has shown that some organic amendments are capable of eliciting hormonal growth responses in plants, or can lead to the production of plant growth-promoting substances in soil. Examples include extracts from seaweed, and low molecular weight humic substances, particularly those in vermicomposts.

• Enhancement of soil organic carbon. Most organic amendments, except those with relatively low carbon contents, will increase the organic content of soil. However, the longevity of this carbon depends on how the soil is managed and whether the amendment is continually reapplied. Soil carbon will be lost if the soil is repeatedly tilled, and reapplication is required to maintain microbial biomass carbon. Also, some amendments, especially materials with a relatively low C:N ratio, may stimulate microbial activity to such an extent that they increase carbon mineralization, potentially reducing the amount of organic carbon in soil.

• Soil structural benefits. The capacity of organic amendments to improve the physical condition of soil is well documented for materials such as composts and crop residues, which are applied at relatively high application rates. However, humic substances, which are usually applied at much lower rates, may produce similar effects, as they have the capacity to bind with clay minerals and promote aggregation.

Impact of organic source and application rate on disease suppression

In addition to these effects, the role of organic amendments in enhancing suppressiveness to a range of soilborne diseases is well documented. Bonanomi et al. (2007) assessed the results of 2423 experimental studies and found that amendments enhanced suppression in 45% of cases. Disease incidence increased in 20% of the experiments and there was no effect in the other experiments. Composts and organic wastes were the most suppressive materials and usually did not increase disease incidence. Crop residues were often suppressive, but could also be conducive to disease, while peat enhanced suppressiveness in only 4% of the experiments. The ability of amendments to suppress disease also varied with different pathogens. Suppression was commonly observed (>50% of cases) when the disease was caused by Verticillium, Thielaviopsis, Fusarium or Phytophthora, whereas it was rare for diseases caused by Rhizoctonia solani.

Application rate also has major effects on the capacity of an amendment to suppress disease. Thus, disease suppressiveness increased with application rate in about half the experiments assessed by Bonanomi et al. (2007), and was also noted by Noble and Coventry (2005) in their review of the suppressive effects of composts in field situations. This highlights the fact that in many published studies, high application rates were required to achieve immediate disease control. Work on organic amendments in Canada provides a good example. A variety of soilborne diseases of potato were controlled with solid materials (meat and bone meal, soy-meal and poultry manure) at rates of 15–66 t/ha, and liquid swine manure at 5500 L/ha (Lazarovits et al., 2001). However, some of these amendments, particularly the meat and bone meal, and soy-meal, were not an option for most growers, as they were too expensive. Thus, despite good experimental evidence of effectiveness, the cost of purchasing a suitable amendment and transporting it to the required site is often prohibitive, even in high-value crops. Consequently, future research efforts must take a longer-term view of how such materials are used. We need to apply amendments at realistic application rates and recognize that the benefits of adding organic matter to soil are incremental, that the effects are cumulative, and that it takes time to develop disease-suppressive soils (Bailey and Lazarovits, 2003).

Effects on pathogen populations and disease

Organic amendments do not always reduce disease incidence or severity by reducing populations of the pathogen. Although this commonly occurs with Thielaviopsis and Verticillium, effects are variable with Phytophthora and Fusarium, while population densities of oomycetes and fungi that are aggressive saprophytes (e.g. Pythium and Rhizoctonia) often increase (Bonanomi et al., 2007). Thus, there is not necessarily a correlation between disease suppression and pathogen population density, presumably because amendments sometimes act by inducing plant resistance, improving soil physical or chemical properties, or enhancing biostatic mechanisms that inhibit rather than kill the pathogen.

Variation in responses to organic inputs

It is obvious that many types and sources of organic matter can be used to enhance general suppressiveness and that they are effective in many different situations. However, results tend to be inconsistent, as plants and pathogens do not always respond in the same way to organic amendments, and efficacy is influenced by environmental conditions. Also, the level of suppressiveness varies with the nature of the inputs, the degree to which they have decomposed, and the rate at which they are applied (Scheuerell et al., 2005; Bonanomi et al., 2007, 2010). Pathogens that are good primary saprophytes but poor competitors (e.g. Pythium and Fusarium) will multiply on fresh organic matter and then be suppressed by organisms involved in the decomposition process, so the time taken for these competitive organisms to become dominant, and for suppressiveness to develop, must be considered when organic matter is used to manage such pathogens. Enhancing suppressiveness to Rhizoctonia, a diverse genus that contains many plant pathogens, is also problematic. Aggressive isolates of R. solani, for example, have a number of intrinsic properties that make them difficult to control: a capacity to colonize fresh organic matter; mycelium that grows rapidly but does not degrade readily; and sclerotia that are insensitive to fungistasis and resistant to decomposition. Therefore, successful inhibition of this fungus relies on creating a biological environment where soil microorganisms compete with the pathogen for colonization sites on organic matter, and pathogen-specific antagonists are also active (Stone et al., 2004).

The problems involved in achieving consistent control with organic amendments are ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Section I Setting the Scene

- Section II The Soil Environment, Soil Ecology, Soil Health and Sustainable Agriculture

- Section III Natural Enemies of Nematodes

- Section IV Plant–Microbial Symbiont–Nematode Interactions

- Section V Natural Suppression and Inundative Biological Control

- Section VI Summary, Conclusions, Practical Guidelines and Future Research

- References

- Index of Soil Organisms by Genus and Species

- General Index