![]()

1 The Genome of Pristionchus pacificus and the Evolution of Parasitism

Ralf J. Sommer and Akira Ogawa

Max-Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tübingen, Germany

Introduction

From an evolutionary perspective, parasitism represents a derived character. That is, all parasitic life on earth derives from free-living ancestors. Molecular phylogenetics made the convincing argument that, within nematodes, parasitism has evolved multiple times independently. Based on the phylogenies of Blaxter et al. (1998) and Holterman et al. (2006; van Megen et al., 2009), animal parasitism has evolved at least four times and plant parasitism at least three times within the nematodes. In contrast, many other parasitic taxa, such as the Trematoda or the Nematomorpha, are believed to represent fully parasitic taxa. This distinction makes the nematodes a superb phylum in which to study the evolution of parasitism. First, free-living relatives of present-day parasites are often available in nematode clades. Such species might share some characteristics with ancestral precursors of parasites and therefore might indicate evolutionary trends towards parasitism. Second, the parallel evolution of parasitism within nematodes provides the opportunity to compare different routes towards the parasitic life style and to identify shared characteristics.

For a long time, considerations about the evolution of nematode parasitism, in particular animal parasitism, were based on theoretical studies. However, recent advances in molecular biology, genomics and genetics in various nematode species have provided first experimental insight into the transitions towards parasitism and corresponding life-history adaptations. Here, we summarize recent experimental studies in the genetic model species Pristionchus pacificus that focus on genome evolution, the genetic regulation of dauer larvae and infective juvenile formation, and the evolution of predation.

Theoretical Considerations

All parasitic life on earth derives from free-living ancestors and while parasitism has evolved many times, the transition towards parasitism itself is a very slow process. As a result, such transitions cannot easily be observed in the wild in present-day species. Also, it is impossible to predict whether a present-day free-living organism is on a clear ‘route’ to becoming a parasite. With these caveats of evolutionary processes, there have been only limited experimental attempts to study the evolutionary transition towards parasitism. In principle, there are two main obstacles: If one studies a present-day parasite, the major event for the evolution of parasitism – the transition itself – has already occurred. On the other hand, if one studies a free-living species there is no guarantee that the organism under consideration will ever evolve into a true parasite because evolution cannot be foreseen. It is this dilemma that has resulted in the near absence of experimental studies on the evolution of parasitism.

While experimental studies on the topic are still in their infancy, there have been several theoretical investigations that have resulted in a conceptual framework. Osche (1956) was the first author to consider the evolution of parasitism in nematodes and was followed by Poinar (1983), Anderson (1984), Weischer and Brown (2001) and most recently Poulin (2007). In the following, we briefly summarize the argument by Poulin, who has discussed the issue in the most comprehensive manner.

The transition towards parasitism requires a contact between a ‘parasite-to-be’ and its future host. However, this contact is not the only precondition that is important for becoming a parasite. Rather, the ‘parasite-to-be’ must possess certain characteristics that allow it to: (i) identify the host in a specific manner; (ii) survive in or on that host; (iii) obtain food; and (iv) successfully reproduce in this new environment. These characteristics have often been called ‘pre-adaptations’ to explain the fitness benefit that has to be assumed for the ‘parasite-to-be’ to start host exploitation (Rothschild and Clay, 1952; Osche, 1956; Poulin, 2007; Dieterich and Sommer, 2009).

These pre-adaptations are the true challenges for the understanding of the transition towards parasitism. The concept of pre-adaptation argues that transitions towards parasitism are facilitated by an organism’s current environment and adaptations associated with such an environment (Dieterich and Sommer, 2009). Thus, pre-adaptations are adaptations to the current environment of the ‘parasite-to-be’ and to its life style. In the future, such adaptations might be co-opted to new functions to facilitate the transition to a new (parasitic) environment. Pre-adaptations might therefore be helpful for an organism to acquire a new niche.

Life-history Adaptations

Many free-living rhabditid nematodes live in a saprobionthic environment. Osche (1956) and most recently Sudhaus (2008) have argued that adaptations to the saprobionthic life were crucial pre-adaptations for the transition towards parasitism. Two innovations have been given special consideration in this context. First, rhabditid nematodes can form arrested dauer larvae as a long-term survival strategy. Second, these dauer larvae, which will be discussed in more detail below, allowed the acquisition of specific behavioural traits: dauer larvae can attach to insects or other invertebrates and the worms can use these ‘hosts’ for transportation and/or for shelter.

When looking at nematode–invertebrate associations in more detail, several different forms of association can be distinguished. While not all authors agree on exactly the same nomenclature, we want to briefly summarize some of these associations below. For that, we use the nomenclature created by Sudhaus (2008).

BACTERIAL FEEDING SAPROBIONT. As an initial state, one can assume bacterial-feeding nematodes that live in saprobionthic environments. Saprobionthic environments derive from decaying organic matter and they are short-lived and patchy in distribution. Some adaptations to this environment can already be seen as ‘pre-adaptations’ towards parasitism because organisms living in a saprobionthic environment have to deal with low oxygen concentrations and unpredictable conditions. Often, saprobionthic environments allow only survival, but not reproduction of a given organism. Species that introduce resting stages into their life cycles have a major fitness advantage under these conditions. Nematodes have evolved several strategies that involve developmentally arrested stages (Ogawa and Sommer, 2009). The most prominent and important one is the formation of the specialized dauer stage: most saprobionthic nematodes form dauer larvae.

PHORESY. The term phoresy describes the capability of an organism to use another organism (i.e. an insect) for transportation, i.e. between saprobionthic environments. Usually, the specialized stage in the nematode life cycle used for transportation is the dauer stage. Phoretic associations are known from many rhabditid and diplogastrid nematodes, but also others. Poinar (1983) has given a detailed account of the diversity of phoretic associations with invertebrates.

NECROMENY. Necromeny is a Greek term indicating that the animal under consideration waits inside the body of the host for the future cadaver to be decomposed. The necromenic stage is usually the dauer stage. Importantly, animals remain in the dauer stage until the death of the host. Many necromenic associations between nematodes and arthropods or annelids are known. One example that has been intensively studied in recent years is P. pacificus (for recent review see Hong and Sommer, 2006a). P. pacificus and other Pristionchus species live in association with scarab beetles (Herrmann et al., 2006a, 2006b). The genetic, genomic and molecular tools available for P. pacificus have been used to study features associated with their ecology. These considerations will be dealt with below.

ENTOECY. Another type of association is entoecy. In this situation the nematode completes its life cycle in or on the host, but without obtaining nutrients from the host itself. This is different from necromenic nematodes, which do not complete their life cycle on the living host.

MONOXENOUS OR HETEROXENOUS PARASITISM. Real parasites obtain nutrients from their hosts and go through many stages of their life cycle in the host environment. This makes parasitism distinct from necromeny and entoecy. The life cycle of the association can be rather complex, involving intermediate host species. While interesting on its own, this distinction is not of importance for the evolution of parasitism at the outset.

ENTOMOPATHOGENY. Some nematodes carry bacteria in their gut, which help to kill the insect host. The nematode finally feeds on the growing bacteria in the cadaver (Gaugler, 2002). This form of association is different from necromeny in that the nematode ‘brings’ its future food source to the host and uses this for killing. Two important examples for the killing of insects are members of the large genera Heterorhabditis and Steinernema (Gaugler, 2002). Similar phenomena have been observed in molluscs with nematodes of the genus Phasmarhabditis (Rae et al., 2009).

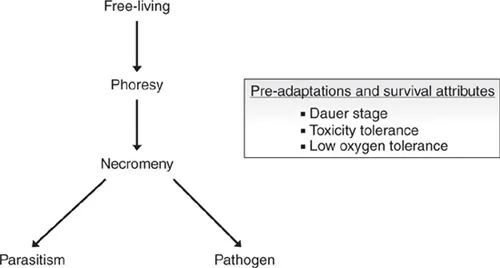

The six categories given above should be seen as part of a continuum of associations. Several authors have used these categories for historical reconstructions of the transition towards parasitism in certain nematode groups (Fig. 1.1). While, unfortunately, there is no perfect phylogenetic congruence, such reconstructions can be helpful as a theoretical framework and they can provide a backbone for experimental studies. However, such experimental studies have to concentrate on individual species in which some of the theoretical assumptions outlined above can be tested in a genetic and molecular manner. The following section will try to summarize some recent inroads from one such model system, P. pacificus.

Fig. 1.1. Life-history adaptations and the evolution of parasitism. Non-parasitic nematode species are free-living in marine, fresh-water and terrestrial habitats, but some species show typical associations with arthropods, other invertebrates and even vertebrates. Phoretic species associate with a host for transportation in an often non-specific manner. Necromenic nematode species associate with a host, wait for its death and then feed on the developing microbes on the host’s carcass. Several studies argued that phoretic and/or necromenic associations provide important pre-adaptations for the evolution of parasitism. Pre-adaptations are adaptations to the current environment of the organism and its life style. In the future, such adaptations might be co-opted to a new function and facilitate the transition to a new environment.

P. pacificus as a Case Study

P. pacificus was originally established as a satellite system in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), but is currently also becoming a model in evolutionary ecology and for studying the evolution of life-history traits. The advantages of P. pacificus for genetic analysis are based on its self-fertilizing hermaphroditic propagation (Sommer et al., 1996). Hermaphrodites are modified females that produce sperm during a short period of larval development to become mature adult females. As long as no real males are around, hermaphrodites will use the self-sperm to fertilize their oocytes. Males can easily be obtained and maintained under laboratory conditions and are used in genetic experimentation (Kenning et al., 2004). From the reproductive point of view, P. pacificus is identical to the model system Caenorhabditis elegans.

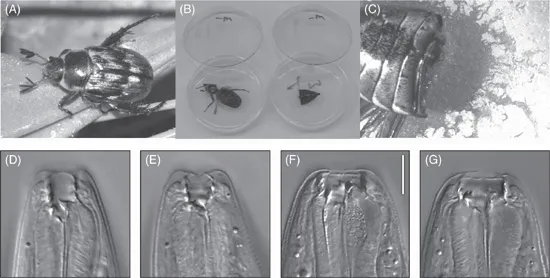

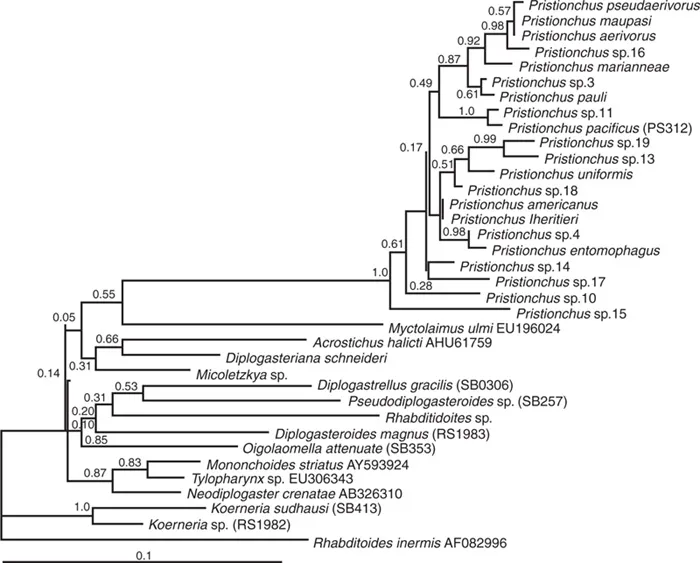

Several Pristionchus species, including P. pacificus, are often found on beetles, particularly scarab beetles (Fig. 1.2; Herrmann et al., 2006a, 2006b, 2007). All Pristionchus nematodes found on living beetles are in the dauer stage (Weller et al., 2010). The dauer larvae of these nematodes stay associated with the beetle and remain there until the death of their hosts, after which development is resumed. Pristionchus nematodes can also be found in soil, but the exchange of soil- and beetle-associated individuals has not yet been investigated. Systematic studies in Europe (Herrmann et al., 2006a), North America (Herrmann et al., 2006b) and Japan (Herrmann et al., 2007) complemented by sporadic samplings in South America yielded a total of 25 Pristionchus species. A molecular phylogeny of the available species provides a framework for studies with the genetic model system P. pacificus (Fig. 1.3; Mayer et al., 2007, 2009). For example, these studies revealed that hermaphroditism has evolved at least five times independently in the genus Pristionchus (Mayer et al., 2007; Herrmann and Sommer, 2011).

Fig. 1.2. P. pacificus biology and life cycle. P. pacificus is often found in association with scarab beetles, such as the Oriental beetle Exomala orientalis (A). Under laboratory conditions, the beetle association can be seen by dissecting beetles on agar plates (B) and following microbial growth (C). P. pacificus forms teeth-like denticles in its mouth, which occur as a dimorphism with stenostomatous (D, E) and eurystomatous (F, G) animals. See text for details.

Fig. 1.3. Molecular phylogeny of Pristionchus and the Diplogastridae family. A maximum likelihood tree of diplogastrid SSU sequences. GenBank accession codes are shown at taxon labels where available, strain designations are shown in parentheses to support strain identification. Bootstrap support values are indicated at nodes. (Redrawn from Mayer et al. (2009) BMC Evolutionary Biology 9, 212.)

P. pacificus is one of a few cosmopolitan species of the genus Pristionchus (Zauner and Sommer, 2007). The first isolate of P. pacificus PS312 is from Pasadena (California, USA; Sommer et al., 1996), but P. pacificus has by now been found in Japan, China, the USA, Bolivia, South Africa and occasionally in Europe, Madagascar, India and Bali. In contrast with other Pristionchus species, P. pacificus shows a wider beetle host range, but it is currently unclear if this is the cause or a consequence of the cosmopolitan distribution. More recent work concentrated on island biogeography identified P. pacificus as a frequent species on the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean (Herrmann et al., 2010). Interestingly, P. pacificus is associated with several scarab beetles on that island and the P. pacificus Réunion strains show a haplotype diversity that represents a substantial amount of the haplotype diversity known from around the world. These findings suggest that the nematode has invaded the island multiple times independently, most likely in association with different scarab beetles. The P. pacificus Réunion system is currently developed as...