![]()

Part I

Animal Abuse: Defining the Problem

Animal abuse is an international problem, which has been part of human civilization for millennia. Despite this, consensus has not been reached on a single definition for animal abuse. This section includes a discussion of the various definitions proposed by experts, a historical perspective of animal abuse and, importantly, examines reasons why some people may be cruel to animals whereas others are caring. To enhance our understanding of the motivations to abuse animals, theories and hypotheses for violent behaviour are explained, as well as an insight into animal rights activists and their campaigns. The incidence of animal abuse among certain members of society, such as children, serial killers and perpetrators of domestic violence is described, along with case study analysis and quotes from animal abusers.

![]()

1 What is Animal Abuse?

Catherine Tiplady

Definitions

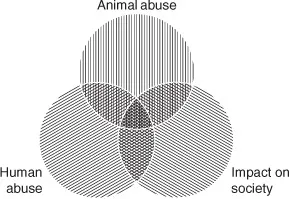

Animal abuse is the deliberate harm, neglect or misuse of animals by humans resulting in the animals suffering physically and/or emotionally. Not only animals but entire communities can be affected by the impact of animal abuse (Fig. 1.1).

Can the terms animal abuse and animal cruelty be used interchangeably and what do they mean? The word ‘cruelty’ is derived from the Latin ‘crudelem’ or ‘morally rough’ (Nell, 2006, p. 211) and ‘abuse’ from the Latin ‘abusus’ meaning to ‘misuse’ or ‘take a bad advantage of’ (Britannica, 1962).

Abuse has been defined as misuse or maltreatment and cruelty as indifference or pleasure in another’s pain (The Concise Oxford Dictionary, 1974). From this it appears that ‘abuse’ can be more widely applied in the context of human–animal relationships whereas ‘cruelty’ focuses on the abuser’s perceptions of the act. It has also been argued that abuse is caused through ignorance but cruelty implies intent by the perpetrator (Rowan, 1993).

There have been a number of attempts to define animal abuse/cruelty and one which is widely adopted is by Professor Frank Ascione. He has defined cruelty as ‘an emotional response of indifference or taking pleasure in the suffering and pain of others, or as actions that unnecessarily inflict such suffering and pain’ (Ascione, 1993, p. 226) and cruelty specifically to animals as ‘socially unacceptable behaviour that intentionally causes unnecessary pain, suffering, or distress to and/or the death of an animal’ encompassing physical, sexual, emotional/psychological abuse and neglect (p. 228). Others have defined cruelty as ‘the wilful infliction of harm, injury and intended pain on a non-human animal’ (Kellert and Felthous, 1985, p. 1114). It has been stated that a feature of abuse is that perpetrators take delight in the harm they cause (Nell, 2006), although some may argue that the perpetrator’s frame of mind is of little consequence to the animals that suffer.

Animal abuse can be physical and/or mental. Physical abuse can be active (including mutilation and assault) or passive (such as failure to provide food and water); mental abuse can similarly be classified as active maltreatment (e.g. instilling fear in the animal) or passive neglect (such as depriving the animal of affection) (Vermeulen and Odendaal, 1993). Merck (2009, p. 65) takes a broad and pragmatic approach, considering that animal cruelty is ‘basically any action or lack of action that results in illness, injury or death of an animal’. Even continuing to use malfunctioning or broken stunning equipment in an abattoir can be considered an act of abuse (Grandin, 2010). Others may consider habitat destruction and extinction of species to constitute animal abuse.

Fig. 1.1. Venn diagram showing overlap between animals, abusers of animals and the rest of society. Abuse of animals is often linked to abuse of people and has impacts on wider society.

Many people consider animal abuse and cruelty to have the same meaning and use the terms interchangeably. One author defines abuse and cruelty as significant harm to animals when a person actively and intentionally harms or fails to act appropriately towards an animal for which he or she is responsible (Olsson, 2010). Most legal definitions require intentionality on the part of the abuser, but this does not affect the impact on the animal. Edwards (2010) defines animal abuse as a deliberate act that inflicts obvious, unnecessary harm and suffering such as starvation, beating, torture, poking out eyes and depriving of water. The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC, n.d.) also describes animal abuse as the intentional harm of an animal. This raises interesting questions about whether unintentional harm of animals could be considered abuse – the dog accidentally run over as he runs out to greet you, the kitten hiding under a cushion, which is sat on and killed, the chick squeezed to death by a small child. If all of these occur unknowingly and unintentionally, then they are not strictly abuse but rather accidents that have resulted in animal harm.

Children may lack a clear definition of animal abuse. Pagani et al. (2010) asked children for their thoughts on animal cruelty, and they raised a range of valid points such as whether cruelty included killing flies, going fishing, not cleaning your fish tank and keeping birds in a cage. The issue of children and animal abuse will be discussed further in Chapter 3.

For the purposes of this book, abuse and cruelty will be used interchangeably and unless otherwise specified, deliberate neglect will be included as part of abuse or cruelty. ‘Animals’ will be the term used rather than the correct but more cumbersome ‘non-human animals’ and although ‘he’ or ‘she’ will be used to refer to animals where possible, if an animal’s gender is not known the pronoun ‘it’ will be used.

Types of Animal Abuse

Animal abuse can occur through omission (neglect of the animal’s needs) or commission (knowing abuse) (Phillips, 2005), and determining which it is can be difficult. Beating a dog to death obviously involves commission but some examples of omission (such as failing to supply adequate food and water to an animal) can be undertaken knowingly. This may have the aim of preventing later animal suffering. Intentional overstocking in sheep, as a method to prevent over-fatness and subsequent dystocia, is an example of this (Joyce et al., 1976).

Where Can Animal Abuse Occur?

Animal abuse may occur:

• in the home;

• in wild animals living free;

• in hunted and fished animals;

• in zoos, tourist attractions or animal sanctuaries;

• where animals are used in sport, work or leisure;

• in farmed animals;

• in guard, guide, draught and work animals;

• in research animals;

• in animals in veterinary clinics, shelters or pounds; and

• in animals you have met.

Abuse can occur anywhere that humans and animals interact.

Issues Impacting on our Acceptance of Animal Abuse

Cultural aspects of animal abuse

People’s attitudes toward and acceptance of animal abuse may vary depending on their culture, the species of animal and the animal’s intended use.

Cock fighting and bear baiting, for example are generally considered cruel in Western culture yet considered sport in others. Slaughter methods and husbandry techniques may also be considered cruel by some cultures but acceptable by others. In most legal texts, ‘harm to animals is not considered cruelty or abuse if it takes place within accepted agricultural, management or research practice and if the harm is not greater than considered necessary to obtain the purpose’ (Olsson, 2010, p. 16). This means that those animals in agricultural or research systems are potentially vulnerable to legally sanctioned abuse.

Many people accept some types of animal abuse, dependent on the species of animal. When developing an interview to assess childhood cruelty to animals, Ascione et al. (1997) differentiated between invertebrates (e.g. worms, insects), cold-blooded vertebrates (e.g. reptiles, fish) and warm-blooded vertebrates (e.g. mammals and birds), with abuse of the latter being considered the most severe. ‘Speciesism’ such as this was refuted by Singer (1995), whose book Animal Liberation compared speciesism to racism and sexism and inspired the Animal Liberation movement when it was first published in 1975. People’s perceptions towards animals may be affected by other factors. Arluke and Sanders (1996) describe a sociozoological scale where people rate animals as morally more or less important according to a number of factors such as the animal’s perceived ‘cuteness’ and usefulness to humans.

Even within the same species, some animals are abused in the name of sport or food production and others seen as valuable. An example of this is cattle – valuable draught animals in developing nations, considered sacred in India, tortured in bullfighting, pushed to their physical limits as dairy and meat animals and occasionally subjected to terrible abuse during husbandry procedures and slaughter (see Figs 1.2–1.4).

People who work with abused animals will rely on legal definitions of animal abuse or cruelty in order to prosecute offenders, but it is still important that you develop your own perspective on what animal abuse is in your own mind and how it affects you and those around you. Just as every case of abuse affects individual animals in different ways, individual people will be affected differently by seeing and working with the effects of animal abuse.

The aims in writing this book are:

• to help the animal victims;

• to help you understand where there may be connection between human and animal abuse;

• to help you understand why and how abuse happens;

• to help you identify possible cases of abuse; and

• to support those who see, treat or work with abused animals and their carers.

While it is acknowledged that animals may harm or kill other animals (for example, animals fighting with each other or killing other animals to eat), that is not the focus of this book. An exception to this is where human interference is directly responsible for the animal’s harm (for example, using trained terriers to hunt badgers). It is recognized that all animals can potentially have a negative impact on other species and the environment, yet human mismanagement (for example, overgrazing land, habitat destruction, dumping of unwanted domestic animals or allowing them to stray) is often the reason behind this.

Fig. 1.2. A bullfight in Juriquilla, Querétaro, México. Bullfighting is a strong part of the national identity in several countries and until the actual fight, the welfare of the animal is very good. Can a generally well cared for life ever outweigh the suffering inflicted during death? (Photograph courtesy of WSPA.)

Fig. 1.3. Distressed, roped Australian steer exported to Indonesia for slaughter, vocalizing prior to slaughter on Meat and Livestock Australia-installed equipment. (Photograph courtesy of Animals Australia.)

Before we discuss how to help animals and people affected by abuse, it is first necessary to examine the issue of animal abuse from a global and historical perspective. Knowledge of the way animals were treated in the past will assist our understanding of current and future motivations to protect or abuse animals.

Fig. 1.4. A pen of dairy calves. Around the world millions of dairy calves are removed from their mothers every year and sold for slaughter at less than a week of age. Calves of this age would naturally suckle from their mothers 5–10 times a day (Broom and Fraser, 2007). Standards have been proposed to deny transported calves food for up to 30 h, stating this will ‘improve the welfare of calves’ (Dairy Australia, 2011). (Photograph courtesy of Animals Australia.)

References

Arluke, A. and Sanders, C.R. (1996) Regarding Animals. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Ascione, F.R. (1993) Children who are cruel to animals: a review of research and implications for developmental psychopathology. Anthrozoös 6(4), 226–247.

Ascione, F.R., Thompson, T.M. and Black, T. (1997) Childhood cruelty to animals: assessing cruelty dimension and motivation. Anthrozoös 10(4), 170–173.

Britannica (1962) Britannica World Language Edition of the Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press, London, UK.

Broom, D.M. and Fraser, A.F. (2007) Domestic Animal Behaviour and Welfare, 4th edn. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Dairy Australia (2011) Handling bobby calves during transport. Available at: http://www.dairyaustralia.com.au/Animals-feed-and-environment/Animal-welfare/Calf-welfare/Managing-bobby-calf-welfare/Handling-bobby-calves-during-transport.aspx (accessed 19 September 2011).

Edwards, L.N. (2010) Animal well-being and behavioural needs on the farm. In: Grandin, T. (ed.) Improving Animal Welfare: a Prac...