eBook - ePub

Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change

About this book

* Provides specific examples of germplasm research related to climate change threats* Edited by internationally renowned experts in the field* The final chapter of the book draws a synthesis of the many issues raised within the book

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change by Michael Jackson, Brian Ford-Lloyd, Martin Parry, Michael Jackson,Brian V Ford-Lloyd,Martin L Parry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Genetics & Genomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Food Security, Climate Change and Genetic Resources

Robert S. Zeigler

International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines

International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Los Baños, Philippines

1.1 Introduction

In the last two decades of the 20th century, and well into the first decade of this century, food security was essentially absent from any discussions on global development priorities. Hunger, although being mentioned in the first Millennium Development Goal (United Nations, 2010), was seen as a consequence of poverty rather than an absolute supply issue. This was in stark contrast to the high priority food production was given following the end of the Second World War. This shift in attitude was the result of spectacular gains in food production, especially in developing countries that just a few decades earlier were facing persistent famine. The success, often referred to as the ‘Green Revolution’, was fuelled by increasing productivity in staples such as rice and wheat, particularly in Asia and Latin America. The rapid yield growth these cereals enjoyed during the 1970s and 1980s was built on a solid foundation of systematic development of genetic resources.

By the early 1990s, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and Inter-American Development Bank all saw very large drops in their lending for agriculture-related programmes compared with their previous major investments in infrastructure and institutions (Zeigler and Mohanty, 2010). Following the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, commonly referred to as the Rio, or Earth, Summit in 1992, many overseas development assistance agencies shifted their emphasis from agriculture and food security to the environment. Agriculture, it seemed, was the antithesis of a healthy environment and the two could not coexist. Although an obvious fallacy, this attitude remains in some quarters to this day.

This perspective began to change – and change rapidly – with the food price crisis in 2007 and 2008. The prices of rice, maize and wheat spiked to levels not seen for decades, global trade was disrupted, and civil unrest spread across Asia and Africa. Rice, which is the staple food for most of the poorest people in the world and in fact the staple for half the world’s population, was particularly hard hit. High bread prices were among the causes of the rioting that eventually led to the ‘Arab Spring’. Prices quickly subsided but to higher levels than before the crisis. Today, the price of internationally traded rice is 70% higher than in 2005. Because food can make up 50% or more of total household expenditures for hundreds of millions of the very poor, millions of people were forced deeper into poverty and hunger became even more widespread. Food prices rose again in 2010–2011, and 2012 saw severe drought in the North American grain belt, Russia and the Ukraine. In the five years since 2008, these droughts, plus extreme flooding in Thailand and Pakistan, two ‘delayed’ monsoon seasons in South Asia and catastrophic storm surges in the Irrawaddy Delta of Burma (Myanmar), have caused many to speculate that global climate change is threatening agricultural productivity gains.

The interplay between food security and climate change and the means by which genetic resources may contribute to dampening the negative impacts that will be experienced are extraordinarily broad topics. Several authors in this volume directly address the range of changes that are being projected for our global climate. Others deal with how these changes may affect global food production, while in closing specific examples of the traits needed to counteract global climate change are presented. This opening chapter will necessarily be a scan of the issues but, because of my particular expertise in rice, I will draw specific examples from work ongoing in rice genetic resources to serve as the first illustrations of why I believe we will be able to adapt to whatever weather future climate has in store for us.

There are several reasons for my optimism. First, we are already experiencing today whatever severe weather events we will experience in the future. We can just expect that they may be more frequent, more widespread, at times more severe and possibly occurring in places where they did not occur before. That is, the abnormal events today may well be considered normal in the future, but by and large they will not be unprecedented (though I will draw a distinction for sea-level rise and rising night-time temperatures). Second, we have clear demonstrations that problems associated with extreme weather events previously thought to be insurmountable, such as serious flash flooding, can actually be solved. Third, the collections of genetic resources that our predecessors so painstakingly gathered and conserved are intact and without doubt contain many traits that will help our major crops cope with more extreme weather. Finally, enormous strides have been made in generating DNA sequences, relating DNA sequence to plant performance, handling large-scale data storage and analysis, doing crop modelling and making inter-specific crosses. These breakthroughs will enable us to systematically understand and use the vast treasure of traits that the world’s public gene banks hold.

1.2 Food Security

For such a seemingly straightforward concept, the definition of ‘food security’ has been evolving since it became a widely used term in the early 1970s. Initially viewed as globally sufficient and available food supplies adequate to prevent price volatility, the term now encompasses availability, affordability, nutritional value, safety and desirability adequate for an active and productive life. Thus, the definition of food security now encompasses the household and individuals (Clay, 2002).

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is an annual global assessment of food security, broken down by region and country (von Grebmer et al., 2012). It is based on the extent of undernourishment, underweight children and child mortality in the area analysed. Although the GHI has dropped by more than 26% since 1990 and all regions have made progress over that time, it is not surprising that there is considerable heterogeneity among regions. The GHI in Southeast Asia declined by 46%, and in Latin America dropped by 44%. The decline in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has been uneven. South Asia, after a good drop in the early 1990s, has a persistently high GHI of around 22 for the last 15 years, and SSA, while remaining high during the 1990s, has shown a promising decline over the last decade. The high GHI values of 22.5 for South Asia and 20.7 for SSA are not very different, but the enormous differences in total population between the two regions mean that the number of hungry people in South Asia comes close to the entire population of SSA. There is an expected link between economic growth and GHI: as per capita gross domestic income increases, the GHI for the country drops exponentially.

These numbers mask some appalling details. In India, for example, more than 43% of children under five years of age are underweight. Taken as a proxy for adequate nutrition, this is particularly alarming given that early childhood nutrition has been clearly shown to directly affect cognitive abilities, success in school, later health outcomes and adult productivity in the work-force (Victora et al. 2008). Considering the importance of rice as the main staple over much of South Asia, particularly for the poor, it is essential to have ample and affordable supplies of rice to meet demand. As overall nutrition is the determinant of a food-secure population, balanced diets are needed; but, for the very poor, these are simply not an option. Thus, improving staples such as rice for their nutritional content, particularly iron, zinc and vitamins, can be an important way to improve nutrition in poor populations.

Rice remains the most important staple for most of the world’s poor (Gulati and Narayanan, 2002). After growing by 35% between 1960 and 1990, global per capita consumption has remained steady at 65 kg year−1 (calculated by dividing total rice consumption data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) PSD online database by population data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations database FAOSTAT; S. Mohanty, Los Baños, 2012, personal communication). In many Asian countries, however, consumption far exceeds 100 kg per person per year (Chapagain and Hoekstra, 2010). Even in rapidly growing economies such as India and China, per capita consumption has dropped only slightly and appears to be stable. Thus, population growth alone will drive demand for rice over the foreseeable future. Likewise, rice consumption is growing fastest, albeit from a fairly low base, in SSA, followed by Latin America. The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) estimates that the world will need at least an additional 116 million tons of milled rice by 2035, or roughly 25% more than today’s production.

Half of the world’s rice-growing area is irrigated – typically flooded for most of the growing season. Yet, this land produces around three-quarters of the world’s rice supply. Situated in low-lying deltas and coastal regions or large inland river valleys, these areas are susceptible to flooding and storm surges, despite sometimes elaborate canal and drainage systems. Large dams constructed from the 1950s to the 1990s provide irrigation water for large areas of rice production across Asia. Many are dependent on melt water from glaciers. It is noteworthy that seven of the great river systems in Asia have their headwaters in the Tibetan Plateau and derive much of their water from annual melting of snow pack and now, apparently, from rapidly melting glaciers. This could translate into an excess of water over several decades, followed by lower runoff rates much later.

The other half of the rice area depends exclusively on rainfall for its water needs and is therefore much more susceptible to variations in rainfall patterns. Rice is particularly sensitive to drought, moderately sensitive to salinity and, like most other crop plants, dies when fully submerged for just a few days. Not surprisingly, rainfed rice produces only 25% of global rice. Yet, it provides livelihoods for hundreds of millions of mostly very poor farmers and their families.

It should be clear that changes in total rainfall and its distribution could wreak havoc on global rice supplies. Storm surges will cause flooding and seawater intrusion to rice paddies. Higher temperatures and sea-level rise will also be detrimental to rice crops. However, given the very low resolution of our climate models, it is impossible to predict with any degree of precision where these changes will occur, how severe these changes will be and over what time frame. This I do not see as a problem. Many of the detrimental changes predicted in future climate scenarios already adversely affect poor rice farmers, and all are amenable to solutions that in part require access to genetic resources. I find comfort in this ‘convenient convergence’ of research and development objectives targeting the immediate needs of poor rice farmers and preparing the world’s rice production for our future, but unknown, climate.

1.3 Available Genetic Resources

Some controversy exists over when and where rice (Oryza sativa) was domesticated (Sweeney and McCouch, 2007; Huang et al., 2012). It is fairly safe to say that rice was being cultivated at least 10,000 years ago and that it was domesticated from Oryza rufipogon (Khush, 1997; Cheng et al., 2003). Two major subgroups of rice, indica and japonica, led rice genetic resource specialists to conclude that there were two centres of origin. One was thought to be in the tropical regions of South Asia where indica rice varieties dominated and the other near central China where japonica rice dominated (cf. Londo et al., 2006; Vaughan et al., 2003). With the discovery that there are tropical japonica-like traditional varieties and another major group in South Asia called aus rice, things have become somewhat less clear. A recent study based on extensive DNA sequence analysis of indica and japonica varieties has concluded that there may have been only one centre of domestication and that all rice radiated from the Yellow River region (Huang et al., 2012). Because rice was domesticated from O. rufipogon, however, the authors suggest that repeated crosses occurred between increasingly domesticated rice and its wild ancestor, resulting, along with natural mutations, in increasing genetic diversity in rice up until modern times. As early farmers and traders took rice from outside its centre of origin, it could continue to intercross with O. rufipogon, with farmers retaining those new traits that were of interest to them (Kovach et al., 2007). This outcrossing continues today, with ‘weedy rice’ being an irritant to most farmers at one time or another. Thus, the genetic bottleneck of domestication from wild species that restricts genetic diversity in many species was nowhere near as narrow in rice as it was in wheat or groundnut, for example (Huang et al., 2012). This probably explains the extraordinary diversity that we see in the International Rice Genebank at IRRI. This diversity, the sharp distinctions among subgroups of O. sativa and especially the differences among accessions collected from different regions, is beautifully illustrated in Plate 1.

Many collections of genetic resources exist for the world’s principal food crops. Genebanks hold >7 million accessions of crops and their relatives in more than 1700 collections worldwide (FAO, 2010). IRRI holds well over 117,000 rice accessions, mostly landraces, in its genebank, and including almost 4500 accessions of all the wild Oryza species. When IRRI was created in the 1960s to develop new tropical rice varieties and production practices that would transform Asian agriculture, it was readily apparent to its rice breeders that there was simply not enough genetic diversity at hand to work with. So, they began to collect popular traditional rice varieties from around the region (IRRI, 2007). However, once the potential magnitude of their early breakthroughs became clear – the possibility, since realized, that the many thousands of low-yielding landraces would be replaced by a few very high yielding varieties – they set about to systematically collect, characterize and conserve these genetic resources before they were lost forever.

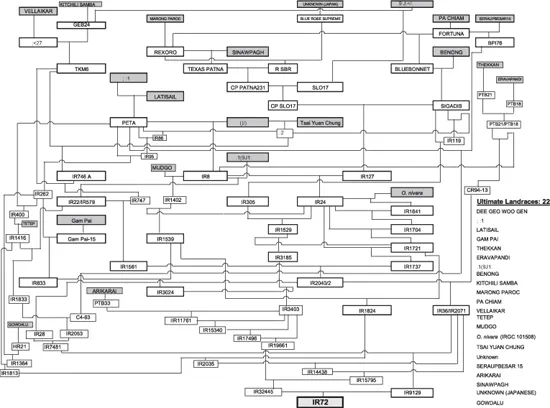

The first widely grown modern semi-dwarf tropical rice variety, IR8, was derived from three traditional varieties (Fig. 1.1). As breeders were compelled to address deficiencies in the early modern varieties, they increasingly turned to traditional varieties as sources for pest, disease and stress tolerance. Occasionally, they were also able to tap closely related Oryza species. The schematic of the pedigree of IR72, a later modern variety released in 1988, clearly shows how frequently breeders tapped traditional varieties (Fig. 1.1). The genetic background for the later varieties is impressive but, typically, only a tiny part of any particular parent can make it into the final variety. This use notwithstanding, and although it was known that some traditional varieties carried tolerance of the major abiotic constraints, efforts to transfer this tolerance to modern varieties generally met with only limited success. Likewise, because crossing a very productive and highly appreciated rice variety with a landrace tends to produce mostly very undesirable progeny owing to linkage drag, breeders are reluctant to make such crosses unless there is no alternative.

Fig. 1.1. Pedigree of rice variety IR72 showing 22 landraces (boxes with bold lines) in its pedigree. In contrast, IR8, the first widely grown modern semi-dwarf variety (indicated by the arrow), had only three landraces in its pedigree.

Modern rice varieties spread rapidly across Asia, with a number reaching the status of mega-varieties. One of the most popular varieties, IR64, covered as much as 35 million hectares and is still widely grown today. So, areas that once supported hundreds and perhaps thousands of traditional varieties came to be covered by a single variety. This spread was accompanied by the development of large irrigation schemes that in turn were justified by the much larger returns from rice farming created by the modern varieties. This ‘chicken and egg’ relationship (which came first?), with mega-environments being created to support mega-varieties, masked an underlying reality of the rice sector. No vibrant seed sector existed that could support the production of more than a few varieties.

Another problem with the mega-varieties was that they were highly susceptible to drought, floods and salinity. Most pest and pathogen problems were tackled fairly early in the breeding process, but progress on the abiotic stresses was essentially non-existent before the turn of this century. Thus, the adoption of modern varieties was limited to irrigated areas with good water control and drainage. Farmer...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Food Security, Climate Change and Genetic Resources

- 2 Genetic Resources and Conservation Challenges under the Threat of Climate Change

- 3 Climate Projections

- 4 Effects of Climate Change on Potential Food Production and Risk of Hunger

- 5 Regional Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture and the Role of Adaptation

- 6 International Mechanisms for Conservation and Use of Genetic Resources

- 7 Crop Wild Relatives and Climate Change

- 8 Climate Change and On-farm Conservation of Crop Landraces in Centres of Diversity

- 9 Germplasm Databases and Informatics

- 10 Exploring ‘Omics’ of Genetic Resources to Mitigate the Effects of Climate Change

- 11 Harnessing Meiotic Recombination for Improved Crop Varieties

- 12 High Temperature Stress*

- 13 Drought

- 14 Salinity

- 15 Response to Flooding: Submergence Tolerance in Rice

- 16 Effects of Climate Change on Plant–Insect Interactions and Prospects for Resistance Breeding Using Genetic Resources

- Index