- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Potatoes are a staple crop around the world. Covering all aspects of botany, production and uses, this book presents a comprehensive discussion of the most important topics for potato researchers and professionals. It assesses the latest research on plant growth such as tuber development, water use and seed production, covers all aspects of pest management and reviews postharvest issues such as storage, global markets, and of course, nutritional value and flavour.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Potato by Roy Navarre, Mark Pavek, Roy Navarre,Mark J Pavek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Botany. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 A History of the Potato

1USDA-ARS, Prosser, Washington, USA; 2Hilversum, the Netherlands

*E-mail: [email protected]

1.1 Domesticating the Potato Crop

The popularity of the potato has fluctuated over the years and it is therefore appropriate to consider the history of the potato leading up to modern times. About 7000 years ago, inhabitants of the Andes in South America were predominantly hunter-gatherers and tended semi-wild herds of native camelids (llamas, vicuñas, and alpacas), yet they began to take an interest in a curious plant (Fig. 1.1). It flowered and produced inedible seed balls, but also produced starchy underground tubers. The tubers were produced at the end of underground stems, oftentimes located a fair distance from the mother plant. The tubers were large enough for a mouthful after cooking and were energy rich. Furthermore, they acted as big seeds, and once planted, they produced potato plants, which in turn produced more tubers. Because the seeds were large, they had enough stored carbohydrates to restart plant growth initially inhibited by a killing frost (International Potato Center, 2008).

Fig. 1.1 Pastoral hunter-gatherers took interest in a plant that yielded edible starchy underground stems about 7000 years ago. (Reprinted with permission from CIP International Potato Center, Lima, Peru.)

The tubers were storable and transportable, and provided nourishment to a society that was in constant motion. Some of the tubers were bitter tasting, but a palatable solution was found. Specific clay soils were used to render the potatoes non-bitter by adsorbing glycoalkaloids into the clay (Johns, 1996). Cultivated potato, Solanum tuberosum Group Stenotomum, is now known to have been selected from the Solanum brevicaule complex, which gave rise to today’s potato (Spooner et al., 2005).

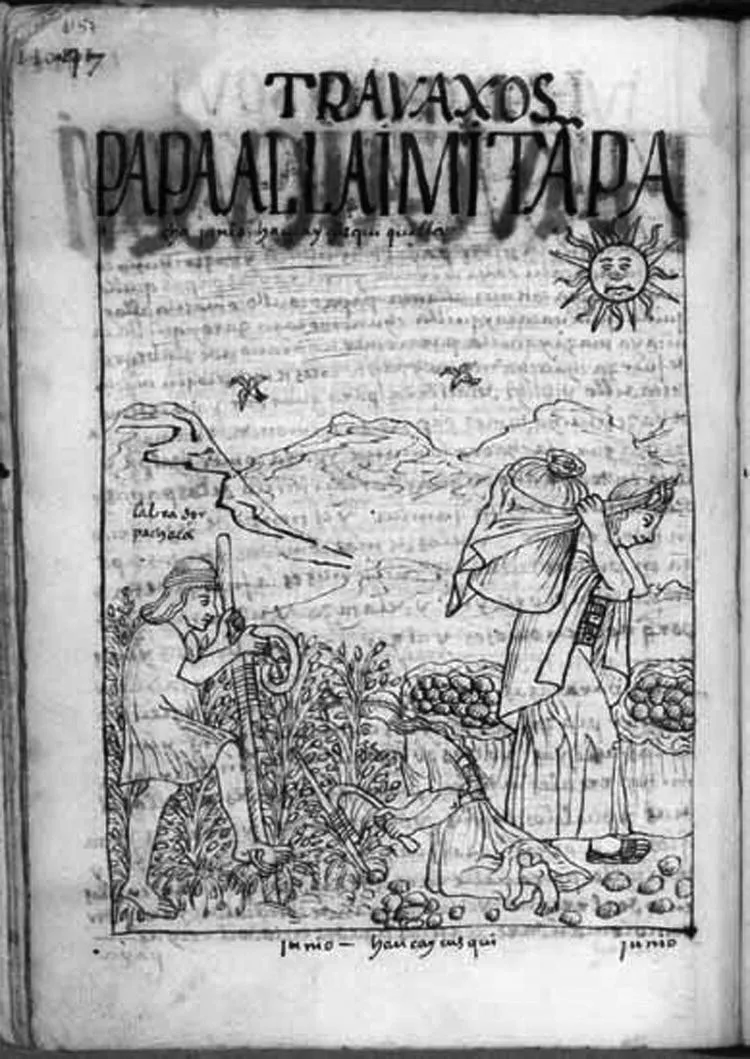

By the time the Spanish arrived in South America, Andean societies were highly organized and had developed agricultural systems, including a collective possession of thousands of types of potato and maize. One of the first descriptions of potato was made by a Spanish soldier in the highlands of Colombia in 1535. A drawing of the potato harvest (Fig. 1.2) comes from the handwritten book scribed by Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, who sought to document the societal interactions of the Spanish and native Quechua-speaking peoples. The drawing depicts harvesting potatoes using the Andean foot plow, or chaquitaccla, an implement still used in the Andes of Peru.

Fig. 1.2 A drawing by Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala depicting the potato harvest, from his historical documentation of Andean society under Spanish rule, Nueva Crónica y Buen Gobierno, 1616.

Guamán’s manuscript was taken to Spain in 1616, ostensibly as a report to King Phillip II, but was given as a gift to the Ambassador from Denmark. It disappeared from view and resurfaced in the Royal Danish Library in 1908. Years of scholarship were required to interpret its archaic Spanish mixed with Quechua (Adorno, 1986). The first facsimile appeared in 1936, produced by the Institute of Ethnography in Paris (Guamán Poma de Ayala, 1615, 1936, 1944). The book is available online, with translations: http://www.kb.dk/permalink/2006/ poma/info/en/frontpage.htm.

Although this remarkable tract documented the major role that potato played in the Andean environment, application of this knowledge to the newly introduced potato in Europe did not occur.

Introducing the potato to Europe

The earliest introductions of the potato in Europe were to the Canary Islands in 1567 and Seville, Spain, in 1570 (Hawkes and Francisco-Ortega, 1992). Sister Teresa de Avila, founder of the Order of the Barefoot Carmelites, eschewed material wealth and took a vow of poverty. Such behavior was considered challenging and embarrassing to the church hierarchy, and she was punished by home imprisonment. While under imprisonment in 1578 in Seville, and having been taken ill, she remarked in a letter that she was fed potatoes and recovered her strength (Oliemans, 1988).

It was also recorded that potato was fed to patients in the Carmelite hospital in Seville, with remarkably curative results. From these references, it can be surmised that potato was grown in some fashion and recognized as a health-restoring food within a few years after its introduction (Salaman, 1949). Yet a vision of potato as a famine preventer did not emerge.

In the Piedmont region of northern Italy, under French control in the late 1170s, came reports of a Protestant group called the Waldensians. The Waldensians were strict adherents to their faith and openly critical of Roman Catholics. Their existence was threatened at various times with extremely violent suppression. Depicted as satanic heretics, they were burned at the stake, forced to flee their homeland, and eventually spread across Europe.

Serendipitously, they had become potato farmers. The potato was more productive than alternative crops and able to support more people on less land than other grains or roots of the time. With each action against them, the Waldensians spread north, seeking the protection of Protestant enclaves as Europe became one large battlefield (Oliemans, 1988).

In a short time, the potato became a major source of sustenance for the Waldensians as they fled north along the Swiss border into France with their potatoes. Potatoes had an additional benefit of escaping taxation, since taxation based on agricultural production was levied at the grain mill. Potatoes did not require milling and thus were not taxed. Waldensians moved into the welcoming Protestant areas of France and Germany, and also the Netherlands (Reader, 2008).

A description of potato was included in Gerard’s Herbal in 1597, which correctly named its origin as Perú (Gerard, 1631). At roughly the same time, the Swiss botanist, Gaspard Bauhin, described the potato in the following passage:

The root is of an irregular round shape, it is either brown or reddish-black, and one digs them up in the winter lest they should rot, so full are they of juice. One put them in the earth once more in spring: should it happen that one leaves them in the sun, in the springtime they will sprout of themselves. Further at the base of the stem close to the roots there spring long fibrous radicles on which are borne the very small round roots. The root itself generally rots when the plant is fully developed. We have judged it our duty to call this plant Solanum by reason of the resemblance of its leaves with that of tomato, and its flowers with those of the Aubergine, its seed with that of Solanums and because of its strong odor which is common to these latter. It is called by some the Pappas of the Spanish and by others Pappas of the Indies. We have further learned that this plant is known under the name of Tartouffoli, doubtless because of its tuberous root, seeing that this the name by which one speaks of Truffles in Italy where one eats these fruits in a similar fashion to truffles.

(Bauhin, 1596)

It is apparent this observer was unaware that the plant was a major food crop underpinning the civilization of the Native Peoples of the Andes. This was as a result of the secrecy maintained around all information coming back from the New World.

Frederick the Great, the young ruler of Prussia in the 1780s, spent considerable time in the Netherlands, studying naval architecture. He came upon the newly arrived potato and sent batches back to Prussia (Salaman, 1949). A French nobleman, A.A. Parmentier, having eaten potatoes while a prisoner of war, promoted its adoption by famously leaving a royal potato planting unguarded at night so that the locals could be introduced to it by stealing it (Parmentier, 1781). Parmentier recognized the stabilizing effect the potato could have on food supply, even when failure of grain crops could lead to famine. The stage was set for an explosion of potato farming and the ability to feed the masses in an agricultural changeover, accompanied by religious revolution and persecution. Far from remaining a botanical curiosity, the potato was becoming the food of the poor.

Even more intriguing was that where the soil and climate were appropriate for potato culture, a startling increase in population occurred in the rural areas and adjacent cities. After the introduction of the potato to the diet of the French Army, records show that the average height of soldiers increased by one-half of an inch (Nunn and Qian, 2011).

In Swiss, the potato was called “erdäpfel”, while in Italian it was called truffle, or “tartouffli”. In France, it became known as “pomme de terre”, and in the Netherlands “aardappel”, earth fruit and earth apple, respectively. In German and Russian, it was called “kartoffel”, a possible sound-alike of “tartouffli”. In Spain, it was called “patata”, again, a sound-alike of the already adopted “batata” or sweet potato. In Great Britain, the word “potato” was used for both potato and sweet potato during a confusing introduction period. Sir Francis Drake wrote indistinctly of potatoes on the island of Chiloé and of potatoes being grown by escaped slaves in the jungles of Panama, referring to Solanum potato in the former and Ipomoea potato in the latter. The next period in potato evolution had a major impact on human nutrition and the global economy.

Cultivation of the potato crop in North America

Barely half a century had passed between the first European appearance of the potato and the potato arriving in the newly founded colony of Virginia, USA. It is remarkable that little mention of the introduction of South American potato germplasm to Europe or North America occurred in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. A partial explanation is that the Spanish were not interested in local foods on arriving in the western hemisphere. Rather, they were intent on recreating Old Spain in New Spain, which meant searching for environments where wheat could be grown, and beef cattle and sheep would prosper. The suitability of cultivating Old World food was, in fact, one of the criteria for establishing a town (Reader, 2008).

Another reason behind the secrecy of potato cultivation was competition and fear of war between England and Spain (Cook, 1973). Nearly all information gleaned from obser...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Content

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 A History of the Potato

- 2 Taxonomy

- 3 Potato Utilization and Markets

- 4 Tuber Development

- 5 Plant Growth and Development

- 6 Commercial Potato Production and Cultural Management

- 7 Plant–Water Relations and Irrigation Management of Potato

- 8 Seed Potato Production

- 9 Insect Pests of Potato

- 10 Plant Parasitic Nematodes of Potato

- 11 Fungal and Bacterial Disease Aspects in Potato Production

- 12 Virus Disease Problems Facing Potato Industries Worldwide: Viruses Found, Climate Change Implications, Rationalizing Virus Strain Nomenclature, and Addressing the Potato Virus YIssue

- 13 Weed Control Strategies for Potato (Solanum tuberosum)

- 14 Tuber Physiological Disorders

- 15 Postharvest Storage and Physiology

- 16 Traditional Breeding and Cultivar Development

- 17 Molecular Breeding of Potato in the Postgenomic Era

- 18 Nutritional Characteristics of Potatoes

- 19 Potato Flavor

- Index