![]()

1

Overview

C.S. Prasad,* P.K. Malik and R. Bhatta

National Institute of Animal Nutrition and Physiology, Bangalore, India

1.1 Livestock Sector

Worldwide livestock are an integral component of agriculture that contribute directly or indirectly to the populace by providing food, value-added products, fuel and transport, enhancing crop production and generating incomes, livelihoods, etc. In addition, livestock also diversify production and income, provide year-round employment and reduce risk. Livestock play an important role in crop production, especially in developing countries, through providing farmyard manure and draught power to cultivate around 40% of arable land. There are 1526 million cattle and buffalo and 1777 million small ruminants in the world (FAO, 2011). Worldwide, these animals are scattered under grazing (30%), rainfed mixed (38.5%), irrigated mixed (30.15%) and landless/industrial (1.15%) production systems. There are interregional differences, too, in the distribution of livestock, attributed to the agroecological features, human population density and cultural norms. Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Near East have a fairly larger land area per person engaged in agriculture, and therefore have a greater livestock proportion dependent on grasslands.

Livestock virtually support the livelihood of about 1 billion poor across the globe, of which 61% inhabit South and South-east Asia (34% in South Asia and 27% in Southeast Asia). Livestock provide over half of the value of the global agricultural output, with one-third in developing countries. This share rises with income and living status, as evidenced from OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, where livestock contribute above 50% of agricultural gross domestic product (GDP). In 2010, the export value of the livestock product in international trading was about US$180 billion, which constituted around 17% of the total agricultural product export value. Approximately 13% of total calorie consumption comes from livestock products on a global scale, while in developed countries this figure increases to ~21% of total calorie consumption. Additionally, livestock products cater to 28% of the world’s total protein need, whereas in developed countries they make up 48% of the total. Due to the comparatively high cost of livestock products and low incomes, the consumption of livestock products in the developing world is still low. However, in the past few years, due to rising incomes and better living standards, a clear transition towards an animal product-based diet is becoming evident in developing countries.

1.2 Trends

The global population is expanding by 90 million per annum, and is expected to reach 9.6 billion by 2050 (UNDESA, 2013). The increase in the population of developing countries will accelerate more compared to that of the sub-Saharan and developed world. In 2050, there will be an escalation of ~70% in population growth in contrast to 1990. There is a concurrent upsurge in people’s income; since 1980, an increase of 1.5% has been recorded on a global scale, while in Asian countries the increase is around 5–7% during the same period. This hike in income is one of the major factors leading to the migration of people towards urban areas; it has been reported that 20% of the total population inhabited urban areas in 1900, which subsequently rose to 40 and >50% in 1990 and 2010, respectively. It is projected that 70% of the population will have migrated to urban areas by 2050. Higher earnings, urbanization and the preference for a better quality diet will shift the majority of people to accommodate livestock products in their meal.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2008) estimated the world’s livestock population comprised 1.58 billion bovines (1.4 billion cattle and 0.18 billion buffalo), 1.95 billion small ruminants (1.09 billion sheep and 0.86 billion goats), 0.025 billion camels and 0.059 billion horses. It is projected that the cattle population might increase to 2.6 billion and small ruminants to 2.7 billion by 2050. This livestock population is not distributed uniformly across continents and countries; one-quarter of the total cattle population is concentrated in Brazil and India, and 56% of total world’s buffalo are residing in India alone (FAO, 2008). The bovine and ovine populations have increased 13 and 22%, respectively, from the 1983 figures. Increasing the population of livestock may be one way to meet the requirement of a large human population in the coming years; however, limited feed and fodder resources, scarce water sources, land shrinkage and climate change pose a restriction on this option and a constant conflict between food–feed crops.

The overall demand for agricultural products including food, feed, fibre and biofuels is expected to increase by 1.1% year–1 from 2005–2007 to 2050, and to meet this increased demand cereal production must increase by 940 million tonnes (Mt) to reach 3 billion tonnes (Bt), meat by 196 Mt to reach 450 Mt, and oil crops by 133 Mt to achieve the necessary figure of 282 Mt (CGIAR, 2014). The world’s demand for milk, meat and eggs will increase by 30, 60 and 80%, respectively, by 2050, as compared to the demand in 1990. The aggregate demand for livestock products is projected to be 70% more in 2050 than that in 1990 (Le Gall, 2013). The growth in milk production is not as much as that seen in meat production over the past few years. However, the consumption of milk per capita per year has increased by 7 kg in the past 30 years (Alexandratos and Bruinsma, 2012). The foremost increase in milk consumption in the past few years has been seen in the developing countries, where consumption has increased by 15 kg per capita per year. To meet the requirement of the population in 2050, an increase of 1.1% per annum from a production of 664 Mt in 2005–2007 has been projected. As milk production in developed countries has already achieved a plateau and is now almost stagnant, this increase in production has hence, out of necessity, to come from the developing countries, where resources are shrinking and productivity enhancement is the only option.

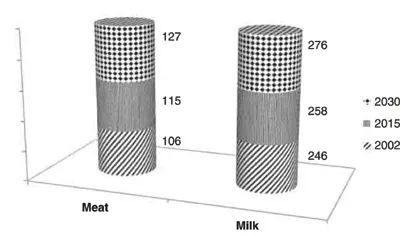

To meet global demand in 2050, meat production will have to be increased at a rate of 1.3% per annum above the 258 Mt produced in 2005–2007 (Alexandratos and Bruinsma, 2012). However, there is a regional disparity projected for this growth; maximum growth in meat production is projected in South Asia (4% per annum), followed by sub-Saharan Africa (2.9%) and the Near East/North Africa (2.2%). For developed countries, the growth in meat production will remain stagnant at around 0.7% per annum. Figure 1.1 shows that meat and milk consumption in comparison to 2002 will increase by 6.4 and 0.49% by 2015 and by 14.10 and 3.47%, respectively, by 2030.

Thus, it is clear from the above discussion that the requirement for livestock products will increase dramatically in future, and the major segment of this increased demand will come from the developing world, which still has much unexplored potential and may be influential in satisfying the requirement of a large human population in 2030/2050. This increased demand shall be met in two ways, either by increasing the number of animals or through intensifying the production potential of livestock, especially in the developing world. However, this is not going to be an easy task for stakeholders, as the livestock sector is currently facing many adversities that need to be addressed urgently. Climate change is one of the major issues adversely affecting livestock production across the world. All the major issues restricting the production from this sector are discussed very briefly in the subsequent section.

Fig. 1.1. Projections for meat and milk consumption (kilogram per capita per annum): 2015/2030. (Modified from Thornton, 2010.)

1.3 Livestock and Climate Change

About one-third of the ice-free terrestrial surface area of the planet is occupied by livestock, which uses almost 15% of global agriculture water. Livestock systems have both positive and negative effects on the natural resource base, public health, social equity and economic growth (World Bank, 2009). Livestock are considered a threat to the degradation of rangelands, deforestation and biodiversity in different ecoregions, and also to supplies of nitrogen and phosphorus in water. As per one estimate, livestock are accountable for 20% of rangeland degradation and pose a threat to the biodiversity of 306 of the 825 ecoregions worldwide (Le Gall, 2013). Animal production systems and climate change are intermixed through complex mechanisms, and the threat of climate change is ubiquitous to the agriculture and livestock sector; however, the intensity of impact is stratified, depending on the agroclimatic region and country. In one way, climatic variations influence livestock production by altering the surrounding environments that govern the well-being and prolificacy of livestock; affecting the quality and quantity of crop biomass, animal health, etc. On the contrary, livestock production also has a large impact on climate change through the emission of the large quantity of greenhouse gases (GHGs) associated with livestock rearing and excreta. Climate change has both direct and indirect impacts on livestock; increase in events such as droughts, floods and cyclones, epidemic diseases, productivity losses and physiological stress are a few of the direct impacts of climate change on livestock, while indirect impacts would be on feed and fodder quality and quantity, the availability of drinking water and the interactions between the host animal and pathogens.

1.3.1 Livestock – the culprit in climate change

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the major GHG accountable for more than half of the greenhouse effect; however, emission from animals as such is negligible and CO2 emits mainly from industries and fuel burning. Though methane (CH4) is the second major GHG, its current atmospheric concentration, i.e. ~2 ppmv (parts per million volume), is far less than the concentration of CO2 (396.81 ppmv). CH4 and nitrous oxide (N2O) are the two major GHGs from animal agriculture that contribute to global warming. Livestock rearing has two components for GHG emissions; one is enteric fermentation and the other is excreta. As such, enteric fermentation contributes almost 90% of the total CH4 emission from ruminants, and the rest comes from hindgut fermentation. The intensity of CH4 emission from excreta depends on the management system followed; the collection and storage of dung in pits or lagoons creates the desirable anaerobic conditions and therefore leads to more CH4 emissions from excreta; however, the emission of CH4 from the heap system in most of developing countries, including India, is much less, as most of the heap portion is exposed to the environment and emission takes place only from the deep inner layer. To the contrary, the N2O emission from the heap system is comparatively more, due to exposure in an open environment.

Both CH4 and N2O have 25 and 310 times more global warming potential, respectively, as compared to CO2, and therefore become more important when global warming is debated. In the total CH4 emission of 535 Tg year–1, 90 Tg is derived from enteric fermentation, whereas 25 Tg comes from animal wastes. Animal production systems emit 7.1 Gt CO2-equivalent (eq) GHGs per annum, which represents around 14.5% of human-induced GHGs. In addition, the ruminant supply chains also emit 5.7 Gt CO2-eq year–1 of GHGs, of which 81, 11 and 8% are associated with cattle, buffalo and small ruminant production, respectively (Opio et al., 2013). In one estimate, the FAO projected that the GHG emissions from the anticipated livestock numbers may be doubled in the next 35–40 years. This shall precipitate much argument, as industrial GHG emission is anticipated to be on the decline.

Further, animal production systems are also the largest contributors of reactive nitrogen to the environment in the form of NH4+, NH3, NO3, N2O and NO. However, most of these nitrogen losses from agriculture, except N2O, do not affect climate change directly, but these compounds have serious environmental consequences by contributing to haze, the acidity of rain, eutrophication of surface-water bodies and damage to forests. The intensification of livestock production to satisfy requirements has led to the rigorous use of manures and fertilizers, resulting in the saturation and accumulation of phosphorus in the soil, which creates the problem of eutrophication and impairs ecosystems.

1.3.2 Impacts on livestock production

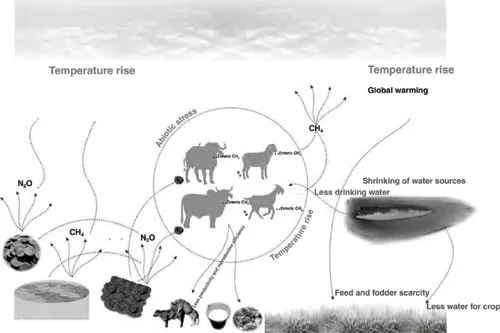

As stated earlier, both livestock and climate change are interrelated by complex mechanisms. Figure 1.2 illustrates the possible interrelated mechanisms by which livestock and climate change impact on each other. In the section above, we have seen briefly how livestock production affects climate change, and in this section, the impact of climate change on livestock production will be addressed in short, as this is deliberated in detail in subsequent chapters. Increasing demand has put pressure on the resource base, leading to more intensification and expansion of livestock production systems. Further, the cropping area in dry regions is also expanding, which forces pastoral livestock systems to relocate into still more arid lands.

Feed and fodders are the key components in livestock production, not only because these are the basic resources that fuel animal productivity but also are the key link between livestock, land and several regulating and provisioning ecosystem services such as water cycles, GHG emissions, carbon sequestration, maintenance of biodiversity and others. As illustrated earlier, livestock production and productivity has to increase substantially from the current level to meet increased demand in the future, which in turn depends on the availability and quality of feed resources; in many projections, crop yields, especially in the tropics and sub-tropics, are projected to fall by 10–20% by 2050, due to a combination of warming and drying. The impact on crop yield may be even more severe in some places.

Fig. 1.2. Inter-dependence of livestock production and climate change.

Stover production in the intensive ruminant production systems of South Asia is now almost stagnant and needs to be complemented with some other alternative feeds to avoid an acute deficit in future. The availability of stover will vary from region to region, and a large increase is anticipated to occur in Africa, due mostly to productivity enhancement in maize, sorghum and millet. Changes in atmospheric CO2 level and temperature will change the herbage growth pattern and pasture composition through the changing grasses to legume ratio. The greater incidences of drought may offset the yield of dry matter with the changing concentration of water-soluble carbohydrates and protein.

Ecosystems inhabited by animals are an amalgamation of biotic and abiotic factors that govern the production and productivity of the animals. Climate change is a major driving factor that exposes farm animals to abiotic stress, particularly to heat stress, which in turn adversely ...