Julia High Performance

Optimizations, distributed computing, multithreading, and GPU programming with Julia 1.0 and beyond, 2nd Edition

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Julia High Performance

Optimizations, distributed computing, multithreading, and GPU programming with Julia 1.0 and beyond, 2nd Edition

About this book

Design and develop high-performance programs in Julia 1.0

Key Features

- Learn the characteristics of high-performance Julia code

- Use the power of the GPU to write efficient numerical code

- Speed up your computation with the help of newly introduced shared memory multi-threading in Julia 1.0

Book Description

Julia is a high-level, high-performance dynamic programming language for numerical computing. If you want to understand how to avoid bottlenecks and design your programs for the highest possible performance, then this book is for you.

The book starts with how Julia uses type information to achieve its performance goals, and how to use multiple dispatches to help the compiler emit high-performance machine code. After that, you will learn how to analyze Julia programs and identify issues with time and memory consumption. We teach you how to use Julia's typing facilities accurately to write high-performance code and describe how the Julia compiler uses type information to create fast machine code. Moving ahead, you'll master design constraints and learn how to use the power of the GPU in your Julia code and compile Julia code directly to the GPU. Then, you'll learn how tasks and asynchronous IO help you create responsive programs and how to use shared memory multithreading in Julia. Toward the end, you will get a flavor of Julia's distributed computing capabilities and how to run Julia programs on a large distributed cluster.

By the end of this book, you will have the ability to build large-scale, high-performance Julia applications, design systems with a focus on speed, and improve the performance of existing programs.

What you will learn

- Understand how Julia code is transformed into machine code

- Measure the time and memory taken by Julia programs

- Create fast machine code using Julia's type information

- Define and call functions without compromising Julia's performance

- Accelerate your code via the GPU

- Use tasks and asynchronous IO for responsive programs

- Run Julia programs on large distributed clusters

Who this book is for

This book is for beginners and intermediate Julia programmers who are interested in high-performance technical programming. A basic knowledge of Julia programming is assumed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Using Arrays

- Array internals and storage

- Bounds checks

- In-place operations

- Broadcasting

- Subarrays and array views

- SIMD parallelization using AVX

- Specialized array types

- Writing generic library functions using arrays

Array internals in Julia

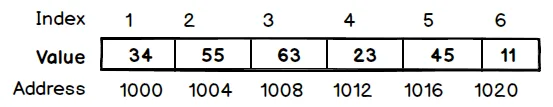

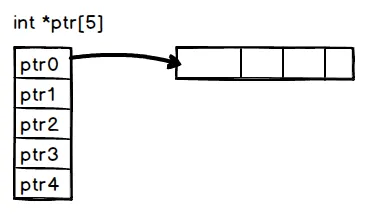

Array representation and storage

You must have realized that type parameters in Julia do not always have to be other types; they can be symbols, or instances of any bitstype. This makes Julia's type system enormously powerful. It allows the type system to represent complex relationships and enables many operations to be moved to compile (or dispatch) time, rather than at runtime.

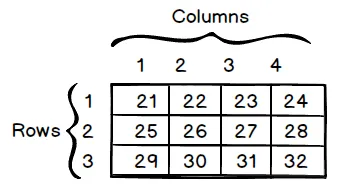

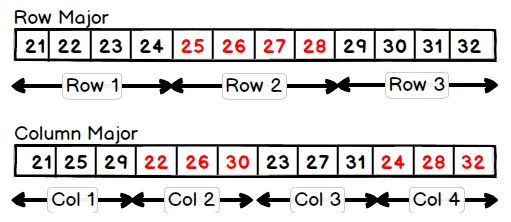

Column-wise storage

Conventionally, the term row refers to the first dimension of a two-dimensional array, and column refers to the second dimension. As an example, for a two-dimensional array of x::Array{Float64, 2} floats, the expression x[2,4] refers to the elements in the second row and fourth column.

function col_iter(x)

s=zero(eltype(x))

for i in 1:size(x, 2)

for j in 1:size(x, 1)

s = s + x[j, i] ^ 2

x[j, i] = s

end

end

end

function row_iter(x)

s=zero(eltype(x))

for i in 1:size(x, 1)

for j in 1:size(x, 2)

s = s + x[i, j] ^ 2

x[i, j] = s

end

end

end

julia> a = rand(1000, 1000);

julia> @btime col_iter($a)

1.116 ms (0 allocations: 0 bytes)

julia> @btime row_iter($a)

3.429 ms (0 allocations: 0 bytes)

Adjoints

julia> b=a'

1000×1000 LinearAlgebra.Adjoint{Float64,Array{Float64,2}}:

...

julia> @btime col_iter($b)

3.521 ms (0 allocations: 0 bytes)

julia> @btime row_iter($b)

1.160 ms (0 allocations: 0 bytes)

Array initialization

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright and Credits

- Dedication

- About Packt

- Foreword

- Contributors

- Preface

- Julia is Fast

- Analyzing Performance

- Types, Type Inference, and Stability

- Making Fast Function Calls

- Fast Numbers

- Using Arrays

- Accelerating Code with the GPU

- Concurrent Programming with Tasks

- Threads

- Distributed Computing with Julia

- Licences

- Other Books You May Enjoy

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app