eBook - ePub

Currencies, Capital, and Central Bank Balances

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Currencies, Capital, and Central Bank Balances

About this book

Drawing from their 2018 conference, the Hoover Institution brings together leading academics and monetary policy makers to share ideas about the practical issues facing central banks today. The expert contributors discuss U.S. monetary policy at individual central banks and reform of the international monetary and financial system.

The discussion is broken down into seven key areas: 1) International Rules of the Monetary Game; 2) Banking, Trade and the Making of the Dominant Currency; 3) Capital Flows, the IMF's Institutional View and Alternatives; 4) Payments, Credit and Asset Prices; 5) Financial Stability, Regulations and the Balance Sheet; 6) The Future of the Central Bank Balance Sheet; and 7) Monetary Policy and Reform in Practice.

With in-depth discussions of the volatility of capital flows and exchange rates, and the use of balance sheet policy by central banks, they examine relevant research developments and debate policy options.

The discussion is broken down into seven key areas: 1) International Rules of the Monetary Game; 2) Banking, Trade and the Making of the Dominant Currency; 3) Capital Flows, the IMF's Institutional View and Alternatives; 4) Payments, Credit and Asset Prices; 5) Financial Stability, Regulations and the Balance Sheet; 6) The Future of the Central Bank Balance Sheet; and 7) Monetary Policy and Reform in Practice.

With in-depth discussions of the volatility of capital flows and exchange rates, and the use of balance sheet policy by central banks, they examine relevant research developments and debate policy options.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Currencies, Capital, and Central Bank Balances by John H. Cochrane, Kyle Palermo, John B. Taylor, John H. Cochrane,Kyle Palermo,John B. Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Banks & Banking. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

CHAPTER ONE

INTERNATIONAL RULES OF THE MONETARY GAME

Prachi Mishra and Raghuram Rajan

In order to avoid the destructive beggar-thy-neighbor strategies that emerged during the Great Depression, the postwar Bretton Woods regime attempted to prevent countries from depreciating their currencies to gain an unfair and sustained competitive advantage. The system required fixed, but occasionally adjustable, exchange rates and restricted cross-border capital flows. Elaborate rules on when a country could move its exchange rate peg gave way, in the post-Bretton Woods world of largely flexible exchange rates, to a free-for-all where the only proscribed activity was sustained unidirectional intervention by a country in its exchange rate, especially if it was running a current account surplus. For more normal policies, a widely held view at that time was that each country, doing what was best for itself in a regime of mobile capital, would end up doing what was best for the global equilibrium. For instance, a country trying to unduly depreciate its exchange rate through aggressive monetary policy would see inflation rise to offset any temporary competitive gains. However, even if such automatic adjustment did ever work, and our paper does not take a position on this, the global environment has changed. Today, we have:

- Weak aggregate demand, in part because of poorly understood consequences of population aging and productivity slowdown

- A more integrated and open world with large capital flows

- Significant government and private debt burdens

- Sustained low inflation.

The pressure to avoid a consistent breach of the lower inflation bound and the need to restore growth to reduce domestic unemployment could cause a country’s authorities to place more of a burden on unconventional monetary policies (UMP) as well as on exchange rate or financial market interventions/repression. These may have large adverse spillover effects on other countries. The domestic mandates of most central banks do not legally allow them to take the full extent of spillovers into account and may force them to undertake aggressive policies so long as they have some small, positive domestic effect. Consequently, the world may embark on a suboptimal collective path. We need to reexamine rules of the game for responsible policy in such a context. This paper suggests some of the issues that need to be considered.

THE PROBLEM WITH THE CURRENT SYSTEM

All monetary policies have external spillover effects. If a country reduces domestic interest rates, its exchange rate also typically depreciates, helping exports. Under normal circumstances, the “demand creating” effects of lower interest rates on domestic consumption and investment are not small relative to the “demand switching” effects of the lower exchange rate in enhancing external demand for the country’s goods. Indeed, one could argue that the spillovers to the rest of the world could be positive on net, as the enhanced domestic demand draws in substantial imports, offsetting the higher exports at the expense of other countries.

Matters have been less clear in the post-financial crisis world and with the unconventional monetary policies countries have adopted. For instance, if the interest rate-sensitive segments of the economy are constrained by existing debt, lower rates may have little effect on enhancing domestic demand but continue to have demand-switching effects through the exchange rate. Similarly, the unconventional “quantitative easing” policy of buying assets such as long-term bonds from domestic players may certainly lower long rates but may not have an effect on domestic investment if aggregate capacity utilization is low. Indeed, savers may respond to the increased distortion in asset prices by saving more. And if certain domestic institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies need long-term bonds to meet their future claims, they may respond by buying such bonds in less distorted markets abroad. Such a search for yield will depreciate the exchange rate. The primary effect of this policy on domestic demand may be through the demand-switching effects of a lower exchange rate rather than through a demand-creating channel. (See, for example, Taylor 2017 for evidence on the exchange rate consequences of unconventional monetary policy in recent years and the phenomenon of balance sheet contagion among central banks.)

Other countries can react to the consequences of unconventional monetary policies, and some economists argue that it is their unwillingness to react appropriately that is the fundamental problem (see, for example, Bernanke 2015). Yet concerns about monetary and financial stability may prevent those countries, especially less institutionally developed ones, from reacting to offset the disturbance emanating from the initiating country. It seems reasonable that a globally responsible assessment of policies should take the world as it is, rather than as a hypothetical ideal.

Ultimately, if all countries engage in demand-switching policies, we could have a race to the bottom. Countries may find it hard to get out of such policies because the immediate effect for the country that exits might be a serious appreciation of the exchange rate and a fall in domestic activity. Moreover, the consequences of unconventional policies over the medium term need not be benign if aggressive monetary easing results in distortions to asset markets and debt buildup, with an eventual disastrous denouement.

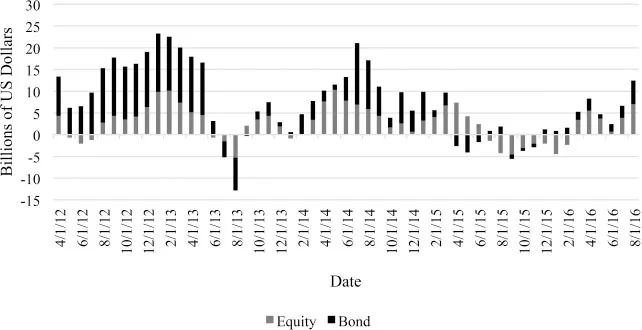

FIGURE 1.1.1. Nonresident Portfolio Inflows to Emerging Market Economies. Source: IMF, “Global Financial Stability Report,” October 2016

Thus far, we have focused on exchange and interest rate effects of a country’s monetary policy on the rest of the world. A second, obviously related, channel of transmission of a country’s monetary policy to the rest of the world in the post-Bretton Woods system has been through capital flows. These have been prompted not just by interest differentials but also by changes in institutional attitudes toward risk and leverage, influenced by sending country monetary policies. Figure 1.1.1, for example, shows that post-global crisis capital flows to EMs have been large. This is despite great reluctance on the part of several EMs to avoid absorbing the inflows.

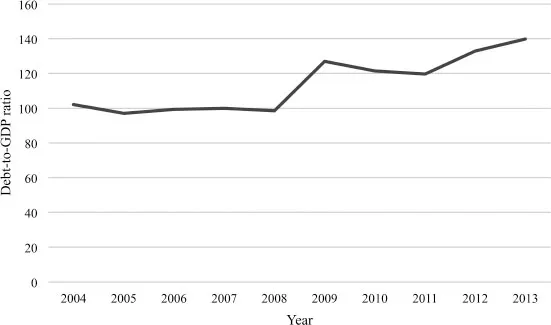

As a consequence, local leverage in emerging economies has increased (figure 1.1.2). The increase could reflect the direct effect of cross-border banking flows, changes in global risk aversion stemming from source country monetary policy (Rey 2013; Baskaya et al. 2017; Morais, Peydro, and Ruiz 2015), the promise of abundant future liquidity on borrowing capacity (see Diamond, Hu, and Rajan 2017, for example), or the indirect effects of an appreciating exchange rate and rising asset prices, which may make it seem that emerging market (EM) borrowers have more equity than they really have (see Shin 2016, for example).

FIGURE 1.1.2. Corporate Debt-to-GDP Ratio for Emerging Economies Source: IMF, “Global Financial Stability Report,” October 2016

The unintended consequence of such flows is that they are significantly influenced by the monetary policies of the sending countries and may reverse quickly—as they did during the Taper Tantrum in 2013. This means that they are not a reliable source of financing, which then requires emerging market central banks to build ample stocks of liquidity (that is, foreign exchange reserves) for when the capital flows reverse. Moreover, the liquidity insurance provided by emerging market central banks to their borrowers is never perfect, so when capital flows reverse, they tend to leave financial and economic distress in their wake. Capital flows, driven or pulled back by the monetary policy stance in industrial countries, create risk on the way in and distress on the way out. They constitute both a costly spillover and a significant constraint on emerging market monetary flexibility.

The bottom line is that simply because a policy is called monetary, unconventional or otherwise, it may not be beneficial on net for the world. That all monetary policies have external spillovers does not mean that they are all justified. What matters is the relative magnitude of demand-creating versus demand-switching effects and the magnitude of other net financial sector spillovers, that is, the net spillovers (see Borio 2014; Borio and Disyatat 2009, 292; Rajan 2013 and 2014, for example).

Of course, a central contributor today to policy makers putting lower weight on international spillovers is that almost all central banks have purely domestic mandates. If they are in danger of violating the lower bound of their inflation mandate, for example, they are required to adopt all possible policies to get inflation back on target, no matter what their external effect. Indeed, they can even intervene directly in the exchange rate in a sustained and unidirectional way, although internationally this could be seen as an abdication of international responsibility according to the old standards. The current state of affairs means that central banks find all sorts of ways to justify their policies in international fora without acknowledging the unmentionable—that the exchange rate may be the primary channel of transmission and external spillovers may be significantly adverse. Unfortunately, even if they do not want to abdicate international responsibility, their domestic mandates may give them no other options. In what follows, we will examine sensible rules of monetary behavior assuming the domestic mandate does not trump international responsibility.

PRINCIPLES FOR SETTING NEW RULES

Monetary policy actions by one country can lead to measurable and significant cross-border spillovers. Such spillovers can influence countries to undertake policies that shift some of the cost of the policy to foreign countries. This temptation to shift costs can create inefficiencies when countries set their policies unilaterally. If countries agree on a set of new rules or principles that describe the limits of acceptable behavior, it can reduce inefficiencies and lead to higher welfare in all the countries. This does not mean countries have to coordinate policies, only that they have to become better global citizens in foregoing policies that have large negative external effects. We had such a rule in the past—no sustained unidirectional intervention in the exchange rate—but with the plethora of new unconventional policies, we have to find new, clear, and mutually acceptable rules.

What would be the basis for the new rules? As a start, policies could be broadly rated based on analytical inputs and discussion. To use a driving analogy, polices that have few adverse spillovers and are even to be encouraged by the global community could be rated green; policies that should be used temporarily and with care could be rated orange; and policies that should be avoided at all times could be rated red. To establish such ratings, the effects of any policy have to be seen over time, rather than at a point in time. We will discuss the broad principles for such ratings in this section. We will then discuss whether the tools economists have today allow empirical analysis to provide a clear-cut rating of policies. (To preview the answer, it is “No!”) We will then argue that it may still be possible to make progress, once broad principles of the sort discussed in this section are agreed on.

A number of issues would need to be considered in developing a framework to rate policies.

- Should a policy that has any adverse spillovers outside the country of origin be totally avoided? Or should the benefits in the country of origin be added to measure the net global effects of the policy? In other words, should we consider the enhancement to global welfare or the net spillovers to others only in judging policy?

- Should the measurement of spillovers take into account any policy reactions by other countries? In other words, should the policy be judged based on its partial equilibrium or general equilibrium effects?

- Should domestic benefits weigh more and adverse spillovers weigh less for countries that have run out of policy options and have been stuck in slow growth for a long time? Should countries be allowed “jump starts” facilitated by others?

- Should spillovers be measured over the medium term or evaluated at a point in time?

- Should spillovers (both positive and negative) be weighted more heavily for poorer countries that have weaker institutions and less effective policy instruments?

- Should spillovers be weighted by the affected population or by the dollar value of the effect?

Some tentative answers follow.

In general, policies that have net adverse outside spillovers over time could be rated red and should be avoided. Such policies obviously include those that have small positive effects in the home country (where the policy action originates) combined with large negative effects in the foreign country (where the spillovers occur). For example, if unconventional monetary policy actions lead to a feeble recovery in some of the advanced countries leading to small positive effects on exports to emerging markets, but large capital flows to, and asset price bubbles in, the EMs, these policies could be rated red. Global welfare would decrease with this policy.

If a policy has positive effects on both home and foreign countries, and therefore on global welfare, it would definitely be rated green. Conventional monetary policy would fall in this category, as it would raise output in the home economy and create demand for exports from the foreign economy. A green rating for such policies would, however, assume that the stage of the financial and credit cycle in the home and foreign economies is such that financial stability risks from low interest rates are likely to be limited.1

It is possible to visualize other policies that have large positive effects for the originating country (because of the value of the policy or because of the country’s relative size) and sustained small negative effects for the rest of the world. Global welfare, crudely speaking, may go up with the policy, even though welfare outside the originating country goes down. While it is hard to rate such policies without going into specifics, these may correctly belong in the orange category: permissible for some time but not on a sustained basis. Even conventional monetary policies to raise growth in the home economy could fall in the orange category if countries are at a financial stage where low interest rates lead to significant financial stability risks in the home and foreign economies.

Clearly, foreign countries may have policy room to respond, and that should be taken into account. Perhaps the right way to measure spillovers to the foreign country is to measure their welfare without the policy under question and their welfare after the policy is implemented and response initiated. So, for instance, a home country A at the zero lower bound may...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- About the Contributors and Discussants

- About the Hoover Institution’s Working Group on Economic Policy