eBook - ePub

Education and Capitalism

How Overcoming Our Fear of Markets and Economics Can Improve

- 364 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Education and Capitalism

How Overcoming Our Fear of Markets and Economics Can Improve

About this book

The authors call on the need to combine education with capitalism. Drawing on insights and findings from history, psychology, sociology, political science, and economics, they show how, if our schools were moved from the public sector to the private sector, they could once again do a superior job providing K–12 education.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Education and Capitalism by Joseph L. Bast,Herbert J. Walberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Bildung & Bildungspolitik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Need for School Reform

Chapter 1

Failure of the Public School Monopoly

Public schools, more accurately called government schools (that is, schools funded and operated by government agencies),1 enrolled 47 million students in the 2000–2001 school year and spent $334 billion, for a per-student average cost of $7,079.2 Approximately 87 percent of school-aged children in the United States attend government schools.

The most distinctive feature of the government school system is its near monopoly on the use of public funds earmarked for education. With a few exceptions, such as for special-needs students, travel and book expenses for children attending private schools in some states, and a few pilot voucher programs operating around the country, private schools are not eligible to receive tax dollars. As a result, private schools must compete against free government schools that typically outspend them by two to one. Not surprisingly, the private market for schooling is small and mostly nonprofit.

The way government schooling is organized ensures there is little or no competition for students. Students are assigned to schools based on where their parents live, and transfers to schools outside a district typically are made only with the approval of administrators of both the sending and receiving schools. Because of their “lock” on public funds, government schools face little effective competition from private schools. The result is a public school monopoly that limits parental choice, is insulated from competition, and is institutionally opposed to significant structural reform.3

Thirty years ago, this method of delivering schooling was widely thought to be a failed experiment. Such prominent writers as Peter Schrag said we had reached “the end of the impossible dream” of providing universal, free, and high-quality public education.4 When Christopher Jencks, a prominent liberal professor at Harvard University, was asked whether government schools were obsolete, he replied, “If, as some fear, the public schools could not survive in open competition with private ones, then perhaps they should not survive.”5

The criticism did not stop, but neither did it lead to the fundamental reforms needed to improve the quality of government schools. During the 1960s and 1970s, defenders of the status quo pointed to modest improvements in some subjects, in some grades, in some parts of the country, and in some years, sowing enough doubt and confusion to slow momentum for change. Voucher advocates were dismissed as mere educational romantics.6 Much the same rhetoric is heard today from government school apologists.7

Beginning in the 1980s, with publication of A Nation at Risk, however, more compelling evidence of the failure of government schooling began to emerge, leading even one-time defenders of the government schools to reconsider their views. Today the case is stronger than ever. What follows is a summary of only the most telling data. Others have written more detailed reviews.8

DISMAL PERFORMANCE AND RISING COSTS

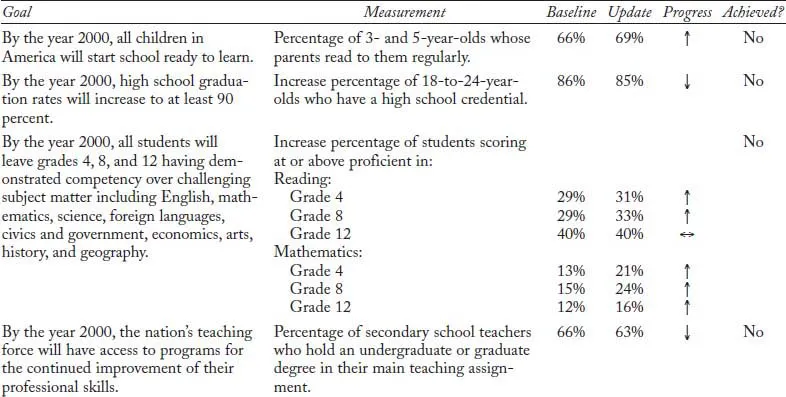

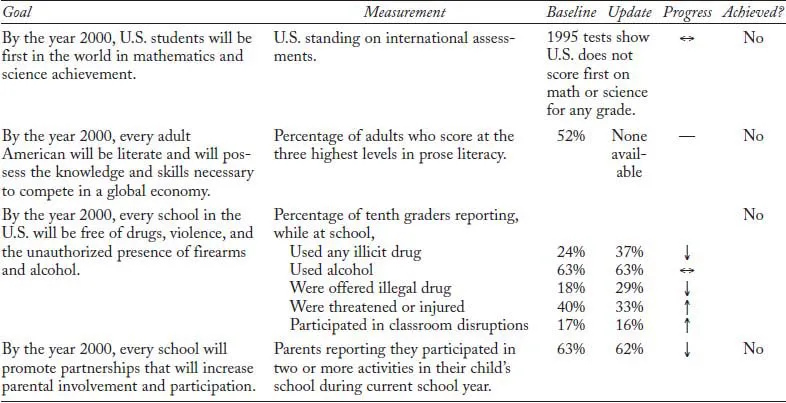

One of the most comprehensive efforts to measure the performance of the nation’s schools was conducted by the National Education Goals Panel, created as an outgrowth of the Education Summit convened in 1989 by President George H.W. Bush and 50 state governors. In 1990, it set six National Education Goals, later expanded to eight by Congress, for the nation’s schools to reach by the year 2000.9

The panel’s 1999 report compared 1990 baseline data with current data on 28 performance measurements. The National Education Goals Panel itself, in a commentary on the tenth anniversary of the goals, admitted that becoming first in the world in math and science is not even remotely within range for the foreseeable future.10 Reviewing other data reveals the same trend.11

Highlights from the report appear in Table 1.1. Graduation rates remained unchanged (as indeed they have since 1973),12 fewer than half (and as few as 16 percent) of students are proficient in reading or mathematics, no progress has been made in making classrooms “free of drugs, violence, and the unauthorized presence of… alcohol,” and parents are no more likely to participate in their children’s schools today than they were a decade ago. Fewer teachers held an undergraduate or graduate degree in their main teaching assignment in 1999 than held them in 1990.

Many studies show that children in poverty often achieve less in school than children in middle-income families. To reduce this achievement gap, for the past quarter-century the federal government has spent about $130 billion on Title I/Chapter I programs aimed at children in poverty. Current expenditures are being made at a rate of about $8 billion a year. Despite this investment, the gap between schools with high concentrations of children in poverty and other schools has remained essentially the same.13

Also worrisome is that, despite substantially rising inflation-adjusted per-student spending for the past half century, achievement test scores on the National Assessment of Progress have stagnated at levels substantially below those in other countries. Even though the United States was third highest in cost-adjusted, per-student spending on K-12 education, our students fell further behind those of other countries the longer they were in school. In reading, science, and mathematics through eighth grade, U.S. schools ranked last in four of five comparisons of achievement progress. In the fifth case, they ranked second to last. Between eighth grade and the final year of secondary education, U.S. schools slipped further behind those in other countries.14

TABLE 1.1 Assessment of National Educational Progress National Education Goals Panel 1999 Annual Report

SOURCE: National Education Goals Panel, The National Goals Report: Building a Nation of Learners 1999, pp. vi, 17–21. Not all changes are statistically significant. See the original for other qualifications.

An 18-nation literacy survey of recent graduates, moreover, showed 59 percent of U.S. high school graduates failed to read well enough “to cope adequately with the complex demands of everyday life,” the worst achievement rate among the countries surveyed.15 Because they made the least progress, U.S. secondary schools recently ranked last in mathematics attainment and second to last in science, results that are plainly at odds with the previously described National Education Goals Panel objective of being “best in the world.”

IMPORTANCE OF SCHOLASTIC ACHIEVEMENT

Policymakers commission international surveys of achievement in reading, mathematics, and science because these subjects are more internationally comparable than, say, civics, history, geography, or literature. They are also particularly important for preparedness for active citizenship, higher education, and the workforce.

Democracy requires well-educated voters, elected officials, and jurors, an observation frequently made by the Founding Fathers, famous historical commentators on the American Experiment such as Alexis de Tocqueville, and contemporary social philosophers as disparate as Amitai Etzioni and Allan Bloom.16 There is wide agreement that schools must teach “recognition of basic rights and freedoms, the rejection of racism and other forms of discrimination as affronts to individual dignity, and the duty of all citizens to uphold institutions that embody a shared sense of justice and the rule of law.”17

Reading is an essential skill in acquiring understanding of nearly all subjects and in achieving happiness in economic and social life. Higher individual and family literacy levels are positively associated with higher income levels, which in turn has a positive effect on such quality-of-life indicators as health and life expectancy.18

Mathematics and science are important because they indicate readiness for further study in such demanding fields as engineering, medicine, and information technology, all fast-growing and competitive sectors in modern economies. Access to workforces with these skills is of critical importance to firms deciding where to locate new plants or corporate headquarters.19

Do achievement test scores really predict objective indicators of individual and national success? The largest and most rigorous survey of adult literacy showed that, in a dozen economically advanced countries, achievement test scores accurately predict per-capita gross domestic product and individual earnings, life expectancy, and participation in civic and community activities.20 According to the OECD, the United States has lost its lead in educating workers for an ever-changing knowledge economy.21 One reason is that U.S. high school graduates read too poorly to upgrade their job skills.

Defenders of the school establishment ask how the U.S. economy could have performed so well during the 1990s if its schools are performing so poorly. If we look at a longer period of time, say the half century from World War II to 2000, we note the U.S. economy grew more slowly than that of the rest of the world. Western Europe and parts of Asia, in particular, largely caught up with and occasionally surpassed the United States in personal income.

During the 1990s, the United States imported from other countries much talent in science, mathematics, medicine, and allied technical fields, enabling it to overcome its education deficit. By 2001, U.S. companies were spending $7 billion a year on overseas outsourcing for software development.22 Because of skill shortages, many low- and high-technology jobs, such as data processing and computer programming, are increasingly exported to other countries, most notably India and Ireland. Relying on other countries to educate our workforce may, or may not, be a successful strategy for the future. But it is plainly evidence of the need for school reform here in the United States.

DECLINING SCHOOL PRODUCTIVITY

Productivity—the ratio of inputs to outputs—is another way to measure the quality of government schools. Like achievement scores, measures of productivity show a system in crisis.23 Harvard economist Caroline Hoxby recently divided average student achievement scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress by per-pupil-spending data from the U.S. Department of Education to estimate the change in productivity between 1970–71 and 1998–99. She found American school productivity fell by between 55 and 73 percent, depending on the skill and age cohort tested.24 According to Hoxby, if schools today were as productive as they were in 1970–71, the average 17-year-old would have a score that fewer than 5 percent of 17-year-olds currently attain.

The falling productivity of government schools can be traced to three developments inside the public school monopoly. The first is growth of a vast bureaucracy of nonteaching personnel. Government schools in the United States report a higher ratio of nonteaching personnel to teachers than government schools in any other developed country.25 In 1997–98, the latest year for which data are available, 12 states had fewer teachers than non-teachers in their government schools workforces.26 In Michigan, for example, teachers comprise ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part One the Need for School Reform

- Part Two Can Capitalism Be Trusted?

- Part Three Education and Capitalism

- Part Four Doing It Right

- Conclusion

- Postscript