![]()

CHAPTER 1

RITES AND PRACTICES OF CONTEMPORARY NEW ORLEANS VOODOO

by Rory Schmitt

Before sharing what many contemporary Voodoo practitioners in New Orleans do, let’s explore what several believe. Without meaning, there is no ritual. Inquiry often reverberates during investigation. Asking questions helps guide the process of understanding key components of New Orleans Voodoo as a religion.

IS VOODOO A POSITIVE BELIEF SYSTEM?

A monotheistic system, Voodoo centers on healing self, others and community. In Voodoo, practitioners see, feel and understand the Divine. They celebrate, venerate and respect Le Bon Dieu, the benevolent Spirit. No devil exists.

WHO ARE THE LWAS?

Lwas, who serve as intermediaries for God, are spirits syncretized as Catholic saints. In Louisiana’s history, it was more acceptable for enslaved laborers to pray to St. Barbara, the patron saint of warriors, than to pray to Shango, the African Vodun god of war. Shango is the Orisha of thunder, lightning and justice, who instructs us how to “pull our power down from the heavens,” says local priest Janet Evans.

In West African Voodoo traditions, Orishas are spirits who share likenesses with the Lwas. Janet Evans explains that the Orishas are guardian spirits who gently guide us to our highest destiny. In the Yoruba religious system, Orishas teach us about love, courage and integrity and remind us of our ancient lineage. An artist raised with Yoruba traditions in Nigeria told me there are so many Orishas that they are uncountable, like the gods and goddesses in Greek traditions.

Each Lwa likes certain items, colors, numbers, foods and drinks, and the offerings that practitioners provide respect the demigod’s wishes. Though each Lwa can handle just about anything, each has a specialty and purpose. Local Voodoo priestess Brandi Kelley explains that each Lwa has a unique identity and history and likes to be honored in a specific way. Let’s examine a few highlighted Lwas:

- OSHÚN: If you are expecting, you might pray to Oshún, who looks over pregnant women. Oshún is syncretized with Our Lady of Caridad del Cobre and Our Lady of Charity. You can offer her yellow flowers and candles, white wine, oranges or peacock feathers.

- EZILI LA FLAMBO: If you are a single mother, you might petition Ezili La Flambo with items in the colors of royal blue and red. Fierce, she offers protection and support to single mothers. During ceremony, she may run around with a dagger.

- ERZULI FREDA: For romance and love, you can call on Erzuli Freda and bring her offerings of perfume, lace and white wine. During ceremony, she is quite coquettish. She often wears a light pink or blue headscarf and carries a fan. She enjoys attention from males.

- OGO: For justice issues, you can petition Ogo, the metalsmith family of Lwas. As Ogo means “fire,” these Lwas’ preferred colors are fiery reds. While some Ogo are wilder and some are more distinguished, it’s important to note that it is a family of spirits, and each has his own personality, preferred foods, liquor, colors and songs that must be prepared for each individual. Ogo are very militaristic, and during ceremony, they might march, click heels, speak boldly and loudly and yell orders to the congregation to get everyone in shape.

- MARASA: For the protection of children, petition the Marasa and share offerings of toys, black and white candles and salt and pepper. They are twins who reflect the sacred duality of opposites and are syncretized with St. Damien and St. Comas. As they are the first children of God, they are the first to be honored at ceremonies. Though ancient, the Marasa twins present as childlike during ceremony. They enjoy eating candies, drinking sweet grape sodas and playfully running all around the temple.

- LEGBA: Before embarking on a journey, seek out Legba, who offers guidance at the crossroads. Legba is the source of communication between the visible, earthly world and the invisible, spirit realm. He is both a benevolent father figure, weary from traveling the world with his children, and a trickster. Often carrying a cane, he is syncretized with St. Lazarus, as well as St. Peter. Practitioners can offer him pipe tobacco, three pennies, bones, rum and Twinkies, Ding Dongs or other Hostess treats; the Lwas want to stay relevant with the changing times, after all!

WHO ARE VOODOO RELIGIOUS LEADERS?

Voodoo priests and priestesses are true leaders, advisors and visionaries in the New Orleans community. Ordained religious leaders in Voodoo include priests (referred to as oungans in Haitian Vodou) and priestesses (called manbos or mambos). However, no organizational hierarchy or gender-based leadership rules Voodoo, unlike the Catholic Church, where all-male leaders include the pope, cardinals, bishops and archbishops.

While Voodoo has ordained female clergy, no ordinations occur in New Orleans. Where clergy are initiated is determined by the type of religion they practice. West African Voodoo is different from Haitian Vodou, and clergy are initiated in places where they feel called. Voodoo centers abroad, such as Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and even as far away as the West African city of Porto-Novo, Benin, now confer ordinations, but in New Orleans, few know about this complex spiritual training.

The priestess’s function is to guide people. She helps practitioners to mediate the spirit. She’s not standing between that person and their relationship with Spirit. The distinction might be that in a Catholic church, the priest stands between the community and God and expresses God’s word. In Voodoo, the priestess facilitates. But each practitioner’s experience is her own, and priest and practitioners all stand as equals with their own relationships with the ancestors.

In Voodoo, male and female Lwas are equally powerful. To see the spirit as male and female may be a paradigm shift for non-Voodoo practitioners. Equality between the genders is symbolic and perhaps transformational. It encourages respect of women and a tolerance for women in power. The Voodoo community often looks up to priestesses, who are viewed as loving, fearless and protective.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF ANCESTORS?

When humans die, their spirits live on as ancestors, who offer protection and guidance to their living relatives and loved ones. Practitioners call out, evoke, invite and recognize their ancestors during ceremonies. Very real and present, they give advice to the living.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HOODOO AND VOODOO?

Common in rural parts of Louisiana, hoodoo includes individualized practices and rituals passed on through families. Ron Bodin, author of Voodoo: Past and Present, explains that hoodoo was developed out of necessity. Before the 1930s, no adequate roads, hospitals or doctors existed, and contact with the outside world was limited. Individuals, particularly those who were disenfranchised and oppressed, were drawn to hoodoo in Louisiana. Hoodoo provided a do-it-yourself religion in order to understand life and regain some semblance of control.

Spellwork and hexes characterize Louisiana hoodoo. Locals from all backgrounds may hire hoodoo practitioners for a variety of reasons: for health, protection, romance or to have elections with results in their favor. Local Vodou houngan Sen Moise explained Louisiana hoodoo and spellwork practices. He grew up with roots in hoodoo and southern conjure and is the owner of Crescent City Conjure in the French Quarter. He explained that southern conjure involves rituals to make a preferred change in your life. You create the conditions, such as fix oils, candles or incense, in order to push that change.

IS IT COMMON TO SEE DIFFERENT WAYS OF PRACTICING VOODOO?

According to Luisah Teish, a Voodoo priestess originally from New Orleans, New Orleans Voodoo is like the local spicy dish of jambalaya. Just as jambalaya involves many ingredients cooked together—shrimp, sausage, tomatoes, peppers and rice—New Orleans Voodoo blends the practices of three continents. Influential elements are: African ancestor reverence, Native American earth worship and European Christian occultism.

While your individual practice of Voodoo can connect to how you were raised, it can also be inspired by encounters with new spiritual traditions with which you resonate. Individual practitioners mold, combine and integrate traditions. For example, some local Voodoo practitioners weave in Judaism and the Qabalah into their practice, while others incorporate the Seven African Powers. Contemporary scholars identify Voodoo as a syncretic religion, which embraces other spiritual practices and adopts qualities of cultures it encounters.

Voodoo practices evolve over the generations. It is important to stress that there are several different forms of Voodoo. New Orleans Voodoo is different from Vodun, which is practiced in West Africa (called Juju in Nigeria), and Vodou, which is practiced in Haiti.

It may be surprising to learn that Voodoo is not restrictive. Voodoo whispers, What does your heart feel connected to? New initiates learn that you can be Catholic and Voodoo. Practicing Voodoo doesn’t require you to abdicate any of your belief systems.

“YOU DON’T FIND VOODOO, VOODOO FINDS YOU”

While some New Orleanians may be born into families practicing Voodoo for generations, increasingly others join later in their lives. Voodoo is not just powerful; it is humbling. With humility, one must ask Spirit for help, clarity and acceptance. One local priestess shared that she respects Voodoo practitioners who have been practicing for twenty years and still feel like they can learn more.

Individuals practice Voodoo in both private and public realms. Legitimate reasons exist for why New Orleans Voodoo practices to this day are largely private. In its New Orleans history, Voodoo was prohibited from being openly practiced in public.

As Voodoo was forced to be a private religion, its practice became more of a solitary spiritual work consisting of sacred practices passed through the generations. Priestess Luisah Teish notes that since New Orleans Voodoo has been nurtured by a servant class with African roots, its practices became daily household acts.

Outsiders of Voodoo shudder when they hear gris-gris, as it was notoriously believed to inject harm. To understand gris-gris, one must learn about its roots in the herbal wisdom of indigenous tribes, as well as African peoples. Herbology for healing purposes dates back centuries in Louisiana. Dr. Martha Ward, an anthropologist and Marie Laveau scholar, explains that founders of Louisiana were dependent on native peoples for their deep knowledge of the land and their skills at using natural elements as medicine. African root doctors were Voodoo leaders who used natural herbs to heal diseases. To this day, Yoruba culture includes phenomenal herbology practices that bring healing with limited side effects.

Gris-gris comes from a Senegalese term and means “charm.” Louisiana enslaved laborers sought African root doctors for gris-gris bags to gain special powers, heal diseases and ward off bad luck. A gris-gris bag strategically placed could give some control over a situation. Gris-gris bags contain natural elements, such as dill seed, fennel seed, gingko leaf, chamomile, clover, black cohosh root, star anise, coltsfoot, althea, damiana and agrimony.

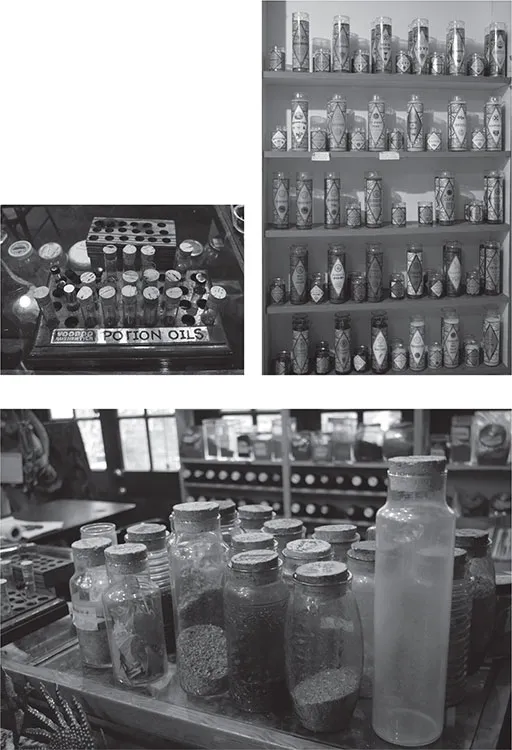

Herbology is a practice of many Vodou religious leaders. This wall features healing herbs at the Island of Salvation Botanica, which is located in the New Orleans Healing Center. Photo by Rory O’Neill Schmitt.

Healing is the core of Voodoo. Potion oils, as well as herbs, including black cohosh root, chamomile and clove, can be found at the Voodoo Authentica store in the French Quarter. Additionally, individuals can purchase colorful candles for luck, protection and love. Photos by Rory O’Neill Schmitt.

A positive charm, gris-gris supports and empowers. Voodoo priestesses share knowledge of how to apply the magical and medicinal powers of herbs. Local spiritual shops, like the Island of Salvation Botanica and Voodoo Authentica, sell herbs used for spiritual work and personal healing. For example, the mandrake root helps soothe the rift between Spirit and matter.

For many cultures, dreams hold significance in healing the psyche, as well as gaining deeper spiritual awareness. In Voodoo, dreams are vehicles for spirit communication. In our dreams, ancestors arrive as warriors protecting us with symbolic signs and gestures.

Like other religions, Voodoo practices have evolved over the years. Once acts done exclusively privately in the home or within small trusted groups of practitioners, they became ceremonies open to the public.

More and more people are drawn to learn about the authentic practices of Voodoo, and they travel from all over the world to find answers. A challenge with Voodoo is that it is viewed as entertainment, religion and a mix of both.

VODOU CEREMONY

In order to explain practices and rituals involved in New Orleans Voodoo, let’s next journey to a Vodou ceremony in the Bywater neighborhood, near North Rampart Street. Woven throughout this narrative is a discovery process with information from literature, as well as interviews, which explain the associated history and symbolic meanings.

Entrance to the Temple

It’s Saturday evening at sunset, and the Uber driver can’t find the Archade Meadows...