- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

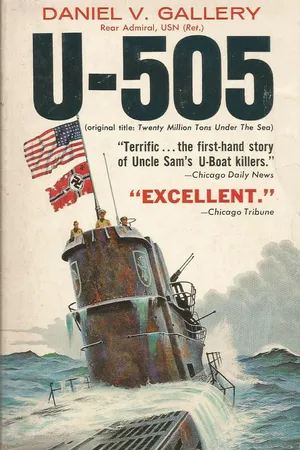

Admiral Daniel V. Gallery boarded and captured a German U-Boat at sea in June, 1944—the first American officer to so capture an enemy warship since 1815!

U-505 is Admiral Gallery's own story of his extraordinary feat—and also a gripping narrative of the fierce Allied war against the German U-Boat fleet.

"EXCELLENT."—Chicago Tribune

"Terrific…the first-hand story of Uncle Sam's U-Boat killers."—Chicago Daily News

"Brimming with thrills."—Philadelphia News

"An engrossing tale…Pungent, entertaining, informative."—Navy Times

"A humdinger of a sea story…a highly readable book, trimmed from stem to stern with the writer's irrepressible sense of humor."—Chicago Sunday Times

"Excellent in several ways: it provides a fine quick survey of the whole Atlantic war, it describes the operation of the German U-boat service, and, most dramatically, it tells how an American task force under Admiral Gallery achieved the unique feat of capturing a German submarine."—Publishers' Weekly

"U-505 IS ONE OF THE WAR'S MOST EXCITING MEMOIRS."—Chicago News

"One of the best non-fiction books about World War II."—Raleigh News & Observer

"A first-rate adventure tale…suspense and excitement told with a seaman's salty zest…excellent reading."—Chicago Sunday Tribune

"A masterful job that merits the attention of every lover of sea stories."—Pittsburgh Press

U-505 is Admiral Gallery's own story of his extraordinary feat—and also a gripping narrative of the fierce Allied war against the German U-Boat fleet.

"EXCELLENT."—Chicago Tribune

"Terrific…the first-hand story of Uncle Sam's U-Boat killers."—Chicago Daily News

"Brimming with thrills."—Philadelphia News

"An engrossing tale…Pungent, entertaining, informative."—Navy Times

"A humdinger of a sea story…a highly readable book, trimmed from stem to stern with the writer's irrepressible sense of humor."—Chicago Sunday Times

"Excellent in several ways: it provides a fine quick survey of the whole Atlantic war, it describes the operation of the German U-boat service, and, most dramatically, it tells how an American task force under Admiral Gallery achieved the unique feat of capturing a German submarine."—Publishers' Weekly

"U-505 IS ONE OF THE WAR'S MOST EXCITING MEMOIRS."—Chicago News

"One of the best non-fiction books about World War II."—Raleigh News & Observer

"A first-rate adventure tale…suspense and excitement told with a seaman's salty zest…excellent reading."—Chicago Sunday Tribune

"A masterful job that merits the attention of every lover of sea stories."—Pittsburgh Press

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1—PROLOGUE

EACH WEEK at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, thousands of wide-eyed school kids explore an eerie, improbable exhibit. It is the ex-German submarine U-505, once one of Hitler’s best U-boats. Boarded and captured by our Navy in 1944 off the West Coast of Africa during the Second Battle of the Atlantic, since 1954 it has rested high and dry among the trees in Jackson Park alongside the Museum near the shore of Lake Michigan.

In Chicago it is now a must for young Davy Crocketts, Supermen, and Captain Videos, to take time out from Indian fighting and space travel, and become Captain Nemos probing the secret vitals of this former enemy ship and brushing elbows with the mysteries of the ocean’s depths. The unique exhibit is dedicated as a memorial to the 55,000 Americans who lost their lives defending our country at sea.

This is a strange end for one of the U-boats that made a shambles of our ocean shipping lanes in 1942-43.…A deadly instrument of war, built to help Hitler conquer the world, becomes a trophy at a museum, a permanent memorial to the American seamen who helped shatter der Führer’s dream of world conquest! A killer that once prowled under the seas jammed with high explosive projectiles for sinking ships is now crowded daily with eager laughing children!

The story of how this came about is one of the epics of World War II. It takes us back a century and a half in naval history to the lusty days when full rigged sailing ships with smooth bore guns slugged it out yardarm to yardarm, and when the cry, “Away all boarding parties,” sent gangs of swashbuckling, salty characters scrambling over the rail with cutlass and marlin spike to board and capture the enemy vessel.

Since the War of 1812, such things have happened only in story books. That kind of naval warfare went out of style with sails and muzzle loading guns. Now naval battles are fought at long range, and when modern weapons hammer an enemy ship into submission, she blows up and sinks.

But on June 4, 1944, a jeep carrier task group of the Atlantic Fleet took a page from the story books by boarding and capturing the U-505, 150 miles off Cape Blanco, French West Africa. It was my great good fortune and high honor to command the task group that did this job. This was the first capture of a foreign man-of-war in battle on the high seas by our Navy since June, 1815, when the American sloop-of-war “Peacock” boarded and seized the British brigantine HMS “Nautilus” in the Straits of Sunda near Singapore.

This statement requires explanation to meet the objections which readers familiar with naval history are sure to raise. I say “foreign enemy man-of-war,” which eliminates captures by either side in our Civil War—and there were very few. I also say “on the high seas,” which eliminates the Spanish ships that we raised from the bottom of Manila Bay or salvaged off the beach near Santiago. I also exclude the many German ships that were turned over to the Allies after the Germans surrendered in World Wars I and II. They were not captured in battle. So far as I have been able to find out from much research, the U-505 is indeed the first foreign enemy man-of-war captured in battle on the high seas by the U.S. Navy since 1815.

The Museum of Science and Industry has gone to great lengths restoring this submarine to its original condition. Everything in the Museum belongs to the modern era and is in working order. This submarine is no exception. The German firms that built the U-505 have cooperated with the Museum in restoring the sub, on the theory that if one of their U-boats is to be on display, they want it to be in such condition that it will at least be a credit to German technology.

The submarine is now practically in operating condition, except for the holes the Museum has cut through the pressure hull so a constant stream of visitors can file through it and see all its complex machinery. There are also a few shell holes in the thin outer plates, put there by my boys in 1944, which the Museum is leaving untouched, perhaps to give evidence that this otherwise healthy looking craft wasn’t built where it now stands. But otherwise the boat is in the same condition as when she was sinking our ships off Panama in 1942.

Everything that you find inside an operating submarine is there: torpedoes, diesel engines, periscopes, pumps, gyro compass, underwater listening devices, radio and radar gear, plus a bewildering array of hand wheels, gages, indicators and switches. It all works, and periodically the Museum kicks the main diesels over for a few revolutions under their own power.

The crew’s spaces, officers’ quarters and captain’s cabin, have the bunks all made up ready for the off duty watch to turn in. The galley range is ready to cook the next meal and pots, pans and crockery are all in their proper places. An official U-boat chart and pencils supplied from Germany are laid out on the Navigator’s table under the ship’s clock which still runs. If her former crew could walk aboard today, they would feel completely at home, and might even get her underway again if they could break her loose from the concrete cradles among the trees!

When I look at the U-505 alongside the Museum now, I can’t help thinking that it was her destiny to wind up at her present moorings from the moment her keel was laid. That submarine and I simply had a rendezvous to keep and neither one of us really had much control over it.

I could easily make out quite a case showing how shrewdly I anticipated every move she made during the last week before we captured her, and took proper action to counter it. In fact, all I’d have to do is to simply lay her track alongside mine on a chart without comment and let the reader draw his own conclusions from the way they converge to a point at 11:20 A.M., June 4, 1944.

But I don’t intend to do this. The German skipper and I both had what we thought were sound reasons for every move we made that last week. Looking back now, our reasons were wrong in almost every case. It was a snafu of errors on both sides in which his mistakes counteracted mine, and produced a fantastically improbable result.

It was much too improbable to just happen that way as a result of pure chance. All of us who did this job know very well that Some One more powerful and wise than any of us was guiding our footsteps that morning. I don’t mean to imply that God took time out from His regular duties to personally intervene in a puny sea battle off the coast of Africa. But it so happened that in World War II we were on God’s side (as Joe Louis put it), and the U-505 was not.

People sometimes say to me, “You were very lucky that day.” I agree with them—up to a point. Apparently our plan of operations for that day agreed with God’s. How much luckier can you be?

There are two ways of “explaining” such things as this, although in my book they both boil down to the same thing. One is to say that life on this earth is controlled purely by chance and that man has no control over his destiny—it depends on the roll of the dice. If you want to defend this proposition, I can give you a list of about twenty incidents in the Battle of the Atlantic which might seem to support it—incidents in which apparently pure chance produced effects beyond any reasonable expectation of their importance.

However, I don’t subscribe to this doctrine. I think this universe was created by an All-Wise Being, for a purpose, and that whatever happens in it, on this puny planet or in the Dark Nebula, over a squillion miles away, happens in accordance with this purpose. In other words, I believe in God.

When you get right down to brass tacks, the people who say it is all luck, believe in Him too. They just call Him by a different name than I do. Nobody with common sense can believe that this wonderfully regulated universe in which we spend our brief lifetime is run by pure chance and nothing else. It is too well-organized, consistent, and logical except for the things that men do. There must be a Controlling Intelligence. I call Him God; agnostics call Him “chance,” “probability,” or “fate.” But call Him what you will, there is an Intelligence greater than man’s that created this universe, is therefore greater than the thing He created, and laid down laws that govern its destiny. When men go crazy and try to destroy themselves, He may nudge the dice that His creatures are rolling and make them come up the way they should. Seafaring men are close enough to God’s handiwork every day to recognize His help when they get it.

The story of the U-505’s capture, told to successive generations of youngsters as they troop through her, will be an inspiration to young Americans for a long time. The ship itself, now peacefully resting among the trees, should be a stern reminder to their elders of the debt this country owes to its seamen, who in two World Wars fought grim mid-ocean battles against prowling killers like the U-505, bent on destroying the sea power which keeps this country of ours alive.

Few Americans realize how close we came to losing both those battles, and what the disastrous result of losing them would have been. In April 1917, the Allies nearly lost World War I at sea. Churchill, in his World Crisis says of this period: “The U-boat was rapidly undermining not only the life of the British Islands, but the foundation of the Allied strength, and the danger of their collapse in 1918 began to loom black and imminent.”

Twenty-five years later, in April 1942, a similar desperate crisis was at hand. In April, May and June, we lost over two million tons of ships. Had that rate of loss continued a few more months, Hitler might have won the war.

Writing of this period in the Second World War, Churchill says, in Their Finest Hour, “The only thing that really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril…”

The two Battles of the Atlantic will never take their proper place in the public mind as crucial campaigns in world history. They lacked glamor and headline appeal. They were relentless, drawn out, monotonous struggles that covered a whole ocean and lasted four to five years. The tempo was slow, and the action repetitious.

Only forty years ago a great naval battle was the most spectacular event of history, jammed with violent, fast moving and dramatic action. In a few hours a naval battle fought within visual range of all ships involved, could settle the fate of nations for years to come. The battle reports of every ship in the action could be expanded into an exciting book. There’s a whole shelf full of such books about Jutland, fought in 1916.

But the battle reports in the Atlantic struggles were tables of cold dreary statistics, balancing the tonnage of merchant ships sunk against that of new ships launched and of new submarines joining the pack against wolves killed since the last table was compiled. These statistics were jealously guarded secrets until the war was over and then nobody cared about them anymore. There were occasional moments of high drama, like the Night of the Long Knives, Murmansk Convoy PQ17, and other great convoy battles, the sinking of “Bismarck,” “Graf Spee” and “Hipper,” and the Channel break of the “Scharnhorst,” “Gneisenau” and “Prinz Eugen.” But these were mere incidents in the overall campaign. The real story is in tables of statistics which read as dramatically as the telephone book to all except a few naval men. For this reason the Battles of the Atlantic will never be enshrined in our national memory alongside those of John Paul Jones, or the Battles of Manila Bay, Guadalcanal, and San Bernardino Strait, although the Battles of the Atlantic were much more decisive than any of these in shaping the future of our civilization.

The British understood this much better than we do. Prolonged periods on a hunger diet have impressed it on two generations of Englishmen as it has never been impressed on us whose country is self-sufficient in food production and has not yet been blitzed.

Until we broke the back of the U-boat fleet early in 1943, the control of the seas so vital to the existence of the free world hung in a precarious balance. Had we lost this control, the United States’ great industrial machine, that supplied the sinews of war to our Allies, would have come to a grinding halt deprived of the strategic overseas imports of raw materials that keep it going. Our vast armies would have been bottled up within our own shore lines, unable to exert any influence on the course of the war in Europe. England faced an even grimmer prospect—slow starvation.

This country of ours has survived two world wars primarily because its industrial capacity has made us invincible—up to now. But our capacity to produce the stuff of war depends absolutely on importing several million tons per year of strategic raw materials which we can only get from overseas. Cut off these imports and you throw our whole industrial machine out of gear because certain essential parts for airplanes, tanks, ships and guns simply cannot be made out of raw materials found in the United States.

This stuff must come in by sea because the number of ton miles involved just cannot be handled by air lift. The great Berlin airlift that bailed us out of trouble in 1948 was a wonderful thing. But the monthly ton mileage involved in this all-out air effort, which taxed the Air Force to its utmost capacity, can easily be moved at sea by two medium-sized cargo ships. Even if it were possible to wave a magic wand and create the colossal fleet of cargo aircraft necessary to haul all our strategic imports by air, this fleet would be a Frankenstein. It would soon burn up the world’s reserve of petroleum and would thus shove us back to the era of sailing ships!

Both Battles of the Atlantic belong on any list of the decisive battles of world history. But between World Wars I and II, in a mere twenty-five years, we forgot the bitter lessons of 1917 and had to learn them all over again in 1942. Let’s hope we don’t forget again, because even in the Atomic Age, to survive we must control the seas.

For two years the U-505 was one of the great fleet of U-boats that challenged our control of the seas and almost wrested it away from us. In her first six months at sea she sank eight Allied ships, totalling 46,200 tons. She is typical of the commerce raiders that prowled the Atlantic and made a shambles of our eastern seaboard early in ‘42.

As time goes on, this submarine in Jackson Park should keep reminding our people, who forget so easily, that sea power is vital to the security of any great nation.

This book tells the story of the U-505, from her keel laying in Germany to her final “docking” in Jackson Park, Chicago. The story is put together from interviews with her crew, and study of her official papers, complete War Diary and logs. The tale of this U-boat, told against the background of the Battle of the Atlantic in which it played an important part, should help drive home the moral of sea power which so few of our people understand, and maybe some other lessons too.

It may show that there was not so much difference between the individual men who met far out on the eternal sea to fight this battle. They were similar human beings with similar motives and emotions, directed by fallible superiors who could make equally bad mistakes. I like to think that our men were fighting for a better cause than the others and that’s why we won.

(NOTE: In telling this story I sometimes quote conversations between crew members of the U-505. Obviously I have no way of knowing whether or not these exact words were said.

(But all the main facts of the story are historically correct and are documented by official records, War Diaries and ship’s logs. The minor incidents are based on interrogation of prisoners, and on letters I have had from the U-505’s crew, who are now back in Germany.)

CHAPTER 2—THE PHONY WAR

THE FIRST six months of the war on land were known as the phony war, but there was no phony war at sea. On the very first day one of Hitler’s U-boat skippers committed a blunder tha...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- CHAPTER 1-PROLOGUE

- CHAPTER 2-THE PHONY WAR

- CHAPTER 3-THE U-505 COMMISSIONED

- CHAPTER 4-INSIDE A SUBMARINE

- CHAPTER 5-SHAKEDOWN CRUISE

- CHAPTER 6-ICELAND

- CHAPTER 7-LOEWE’S FIRST MISSION

- CHAPTER 8-CARIBBEAN CRUISE

- CHAPTER 9-END OF CARIBBEAN CRUISE

- CHAPTER 10-CSZHECH TAKES COMMAND

- CHAPTER 11-LORIENT

- CHAPTER 12-SUICIDE

- CHAPTER 13-THE S.S. “CERAMIC”

- CHAPTER 14-LANGE

- CHAPTER 15-HUNTER-KILLER TASK GROUP

- CHAPTER 16-CRUISE TO CAPE VERDE ISLANDS

- CHAPTER 17-THE CAPTURE OF THE U-505

- CHAPTER 18-CHICAGO

- CHAPTER 19-EPILOGUE

- APPENDIX

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access U-505 by Rear-Admiral Daniel Vincent Gallery in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.