- 358 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

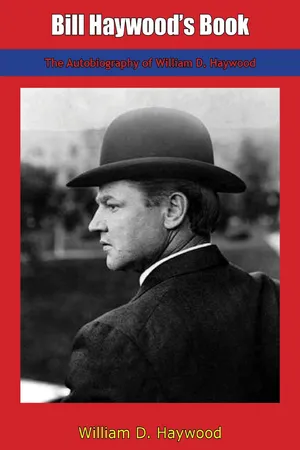

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF 'BIG BILL' HAYWOOD

This is William D. Haywood's own story, written during the last year of his life. An heroic giant of the American labor movement during its most turbulent years, "Big Bill" was a Socialist and a founder and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Born in Salt Lake City, he went into the Nevada metal mines at the age of 15, and joined the Western Federation of Miners in 1896 at 25. At 31, he was Secretary-Treasurer of the WFM, and led its epic struggles against the mining trusts. He became the storm center of many other great labor struggles on the eve of the First World War, including the strikes of textile workers in Lawrence, Mass., and in Paterson, N.J. He also led the militant Wobbly "Free Speech" fights, and was prosecuted for opposing U.S. entry into World War I. His story, a swift moving narrative as absorbing as a novel, should be known to the present generation.

This is William D. Haywood's own story, written during the last year of his life. An heroic giant of the American labor movement during its most turbulent years, "Big Bill" was a Socialist and a founder and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Born in Salt Lake City, he went into the Nevada metal mines at the age of 15, and joined the Western Federation of Miners in 1896 at 25. At 31, he was Secretary-Treasurer of the WFM, and led its epic struggles against the mining trusts. He became the storm center of many other great labor struggles on the eve of the First World War, including the strikes of textile workers in Lawrence, Mass., and in Paterson, N.J. He also led the militant Wobbly "Free Speech" fights, and was prosecuted for opposing U.S. entry into World War I. His story, a swift moving narrative as absorbing as a novel, should be known to the present generation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bill Haywood's Book by William D. Haywood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de la guerre de Sécession. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireCHAPTER I—BOYHOOD AMONG THE MORMONS

My father was of an old American family, so American that if traced back it would probably run to the Puritan bigots or the cavalier pirates. Neither case would give me reason for pride. He was born near Columbus, Ohio, and with his parents migrated to Iowa, where they lived at Fairfield. His brother and cousins were soldiers in the Civil War; all of them were killed or wounded. My father, when a boy, made his way across the prairies to the West. He was a pony express rider. There was no railroad across the country then and letters were carried by the Pony Express, which ran in relays, the riders going at full speed from camp to camp across the prairies, desert and mountains from St. Jo, Missouri, to San Francisco on the Pacific coast.

My mother, of Scotch-Irish parentage, was born in South Africa. She embarked with her family at Cape of Good Hope for the shores of America. They had disposed of everything, pulled up by the roots, and left her birthplace to make their way to California. The gold excitement had reached the furthest corners of the earth. People without the slightest knowledge of what they would have to contend with were leaving for the West. There were no palatial steamships in those days; it meant months of dreary, dangerous voyage in a sailing vessel. The danger was not past when they landed in port; there was still the train ride of eighteen hundred miles, and then the long trip across the plains and mountains in covered wagons drawn by oxen. There was the constant dread of accident, of sickness, and of the hostile Indians, red men who had been forced in self-protection to resent the encroachment of the whites.

On the way across the prairies, my uncle, then a small boy, was lost. The family did not know what had become of him. They searched the long wagon-train in vain. He was in none of the prairie schooners, he was not among the stock drivers who drove the extra oxen, cows and mules. The train could not stop and one family could not drop behind alone to search the boundless prairies. They gave him up for lost and went on with the wagon train, grieving for him. When they pulled down Emigrant Canyon, they saw the beautiful Salt Lake Valley. The dead sea, Great Salt Lake, spread out in front of them. To the right lay the new city of Zion, which had been founded by the Mormons in 1847. Here the family abandoned the wagon-train because of sickness and had to wait for the train following, with the hope that my uncle had been picked up and brought along. It was but a few days after their arrival that my grandmother, walking along the street, saw her son with a basket of apples on his arm. She gathered him up, apples and all, and took him home to his sisters. He had gone with the train ahead and had reached the city a week or two earlier.

My grandmother started a boarding house in Salt Lake City. My father boarded there and met my mother. He was then a very young man; when they married, he was about twenty-two and my mother was a girl of fifteen. I was born on the fourth of February, 1869, before a railroad spanned the continent.

I have but one remembrance of my father. It was on my third birthday. He took me from the house and set me up on a high board fence, which he climbed over, lifting me down on the other side. We went through an alleyway to Main Street, then to a store where he bought me a new velvet suit, my first pants. We called on many of his friends on the way home, and I was loaded with money, oranges and candy. My father died shortly afterward at a place called Camp Floyd, now known as Mercur. When my mother learned of his illness she started for Camp Floyd, taking me with her, but before her arrival he had died of pneumonia and was buried. When we visited his grave, I remember digging down as far as my arm could reach.

Salt Lake City is built in a bend of the Wasatch range. To the east the mountains rise high and stark, to the north is Ensign Peak, near the top of which is a tiny cave that has been explored by all the adventurous youngsters of the town. To the southwest, in the Oquirrh Mountains, lies much of the wealth of Utah. Here are the mining camps of Stockton, Ophir, Mercur, and Bingham Canyon, where is the great Utah copper mine. To the immediate west is the Great Salt Lake, whose waters are so dense with salt that no animal life can survive.

On the islands in the Salt Lake are nests of thousands of seagulls, which are sacred in Utah because of the fact that during a plague of grasshoppers the gulls fed upon the pests, eating millions. They would swallow as many grasshoppers as they could hold, then spew them up and swallow more, and in this way the seagulls helped to save a part of the farmers’ crop, the total loss of which would have meant starvation for the Mormons.

Salt Lake Valley is threaded by the Jordan River, and to the north are warm and hot springs. The grandeur of the scenery and the beauty of the city itself were counteracted by the bad feeling generated by the Mormon Church. Especially was this true during my boyhood days, when the atmosphere was still charged with the Mountain Meadow Massacre, the destruction of the Aiken party, and the threats of the Mormons against the Apostates. These threats were thundered from the lips of Brigham Young, Hyde, Pratt, and other church officials. Of course, they did not make the impression on me that they did on older people, though I remember distinctly some of the features of the trial of John D. Lee, who was a leader of the Mormons and Indians who killed nearly a hundred and fifty men, women and children at Mountain Meadow. The massacre occurred after Lee had got the emigrants to surrender their arms. Lee himself and other Mormons had a bitter hatred against these particular emigrants, who were from Arkansas and Missouri, where the so-called Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, and his brother Hyrum had been murdered in the jail at Carthage, Missouri. I remember seeing a picture of John D. Lee sitting upon his coffin before he was executed at Mountain Meadow. The laws of Utah Territory provided that when a man was sentenced he could take his choice of the means of execution, either shooting or hanging. John D. Lee chose shooting, and was taken from the county seat where he was tried, to Mountain Meadow, the scene of his crime, which undoubtedly had been instigated by others higher in authority. But twenty years passed by between the massacre and the execution in 1877.

It was at about this time that I first saw Brigham Young, the president of the Mormon Church, on the street, although I had seen him before in the Tabernacle, and had heard him deliver his vigorous sermons against apostacy. A short time later he died, supposedly from eating green corn; but rumors were current that he had poisoned himself. If these rumors were true, it was probably because of John D. Lee’s conviction and the demand on the part of the Gentiles, as all non-Mormons were called, for the arrest and trial of Brigham Young in connection with the massacre, at the time of which he had been governor of the Territory, and United States Indian Agent. The Mormons had sensibly cultivated friendly relations with the Indians, and they undoubtedly prevented the massacre of another party of emigrants who came through at about the same time.

The house where I was born was built of adobe, on First South Street, between West Temple and First West. It was divided into four apartments, two on the ground floor and two above. The interesting feature of this house was the family who lived above us, a woman who had been a widow with two grown daughters. At the time of which I write they were all married to the same man, so that the daughters were wives of their own stepfather. Polygamy has always been a religious tenet of the Mormon Church.

Some four years after the death of my father, my mother remarried, and we went to a mining camp called Ophir, to live. Ophir Canyon was steep. On the right the mountains were precipitous, broken with gulches. On the left were lower hills. The canyon widened where the town was built, giving room enough for two or three streets. Lion hill was at the head of the canyon. Over the mountain back of our house was Dry Canyon, where the Hidden Treasure mine was located. At this and other mines of the camp my stepfather worked. The ridge near the Hidden Treasure was strewn with great bowlders of copper pyrites. The Miners’ Delight mine was a tunnel with some open works which were the playground of the boys of the camp. There we found many beautiful crystals which we loved to collect.

Mrs. Whitehead was my first teacher. The schoolhouse at Ophir was built at the upper end of the town and was little more than a lumber shack. From the windows in the late winter we could see the snow slides coming down the mountain side from which all the timber had been cut. The first winter a slide filled the canyon below the town, through which a tunnel had to be cut for the stage to come through, and to let the water out. At the noon recess Mrs. Whitehead would appoint a monitor who would report to her how we behaved in her absence. One day Johnnie O’Neill and I were reported for fighting, and when school was called to order, he was called up and given a whipping with the ruler. I ran pell-mell for the door and home, where I told my mother that I was not going to school any more because the teacher was going to whip me for fighting, and there hadn’t been any fight. That night my mother took me to Mrs. Whitehead’s house and I told them I guessed I knew when I was fighting and when we were wrestling. The matter was patched up and I went back to school the next day. However, Johnnie O’Neill and I had many a fight, both before and after this wrestling match.

One morning I was going to school, which was only a short distance from our house, when I saw Mannie Mills across the street pull his gun from his pocket and shoot at Slippery Dick, who was walking just ahead of me. Dick also began shooting and they exchanged several shots when Mills fell on his face, dead. Several people ran up to him. Slippery Dick blew into the barrel of his six-shooter, put it in his pocket and walked away. I followed him until he went into a nearby saloon. That was the first time I saw a shooting scrape. It was not the only one that occurred in Ophir, which was regarded as one of the wildest mining camps in the West. Another day I went to the scene of a shooting scrape and saw two members of the Turpin family and another man lying dead on the ground.

There was an explosion one night under a corner of Duke’s hotel. The next morning I was in front of Lawrence’s store when a woman, called “Old Mother” Bennet, came walking down the street muttering something about “burning down the town.” A man who was sitting on the edge of the sidewalk jumped to his feet and struck her in the face. It was Johnny Duke, the owner of the hotel. This woman and her man had bragged about planting the powder, and after the incident on the sidewalk both were arrested and the Vigilance Committee drove them down the canyon that very afternoon.

Another day two schoolmates of mine were playing in the livery barn. They were in the room where the hostler slept and found a pistol under the pillow. Accidentally, Pete Bethel pulled the trigger and killed Willie Duke. When I heard the shot I ran to the stable and found Willie dead. I saw the blood running out of his head. Little Pete Bethel was scared speechless.

These scenes of blood and violence happened when I was seven years old. After the talk of massacres and killings at Salt Lake City, I accepted it all as a natural part of life.

It was an event when the Dutch shoemaker’s family arrived in the camp. A day or two after their arrival I was playing down by the creek near the shoemaker’s house when I saw a little girl in the shadow of a clump of willows. Going over to her, I found that she was very pretty, with cheeks like big red apples. When I spoke to her she only smiled. I took her hand, then I kissed her and she seemed to like that. Someone called, her mother, I guessed. Breaking away from me she ran to the house, smiling back at me over her shoulder. The next day I went back and there she was, dipping up a bucket of water from the creek. I went up quietly and put my arms around her, when she turned and scratched my face, spat at me and lifted the bucket as though to throw the water over me. I ran away, not knowing what had come over her. Later I found that it was not she at all; it was her twin sister.

Most of the boys in the camp had slingshots. I was going to make one for myself. I was back of the house trying to cut a handle from a scrub-oak, when the knife slipped and penetrated my eye. They sent me to Salt Lake immediately for medical attention, and for months I was kept in a dark room. But the sight was gone.

When I returned to Ophir, school was closed and I did my first work in a mine. I was then a little past nine years of age. It was with my stepfather, who was doing the assessment work at the Russian mine.

School opened again, and I went another term. This time Professor Foster was the teacher, a stern-looking old Mormon from Tooele, but an excellent teacher. He taught me to understand history, to dig under and back of what was written. He was a lantern-jawed, gray-mustached old man with gray eyes, and I never saw him whip a child.

Hardly a week passed without a fight with some boy or other, who would call me “Squint-eye” or “Dick Dead-eye,” because of my blind eye. I used to like to fight.

After this term of school the family returned to Salt Lake City. Zion, as the Mormons called the city, was intended originally as the capital of an empire of the Mormon Church. When gold was discovered in California, the emigrants swarmed through Utah on their way to the gold fields of the West. Some dropped off at Salt Lake City and stayed, but curiously enough, in spite of the stampede for gold, no Mormons joined in the rush or left their territory.

The Temple Block, where the Tabernacle, the Assembly Hall, the Endowment Houses and the Temple were enclosed within high walls, was the heart of the city; around it everything centered. In the Tabernacle, where eight thousand people could gather, I heard Adelina Patti sing one night when I was a young boy. I have never forgotten it.

The city was built with wide streets that were numbered from the Temple Block. Along the gutters ran streams of mountain water which was used to water the gardens with which every house was surrounded.

The population was divided. Mormons were the dominant factor. The others, even the Jews, were known as Gentiles. The Mormons controlled most of the business and all of the farms. Many of the larger enterprises, factories and farms, were owned by the church, which maintained tithing offices, a newspaper and an historian’s office. The Gentiles of the Territory were miners, business men, saloon keepers, lawyers and politicians. The Deseret News was the official paper of the Mormons, while the Salt Lake Tribune spoke for the Gentiles. Against the Gentiles there was a bitter antipathy, as the older Mormons could not forget the outrages they had suffered, their property that had been destroyed, the killing of their leaders, their final abandonment of the states where they had lived, and their search for a new home where they could be safe from persecution, and which was now being invaded by their old-time enemies. That spirit of bitterness has somewhat died down with the newer generation, but when I was a boy it was at its height.

We lived for years near the house that was my birthplace, in different rented houses, always surrounded by polygamous families; the Taylors, the Evanses, the Cannons. John Taylor, one time president of the Church of Latter Day Saints, as the Mormons call their church, lived across the street from us. He had eight wives in one half block. Next door to our house was one of several families of William Taylor, a brother of the president, and the first house from theirs was the home of Porter Rockwell. He had the reputation of being a Danite, or one of the Destroying Angels, an associate of the notorious Bill Hickman. Concerning these Destroying Angels, it was said that their function was to avenge the church by doing away with such offenders as apostates. Rockwell was a mysterious being to the boys of the neighborhood, most of whom were Mormons. All had heard of the terrible things that he and Hickman were accused of, through rumors and whispers in their families. There was nothing definite, but enough to arouse the curiosity of the youngsters so that when we saw Porter Rockwell on the street, with his long gray beard, gray shawl, gray slouch hat, and iron gray hair falling over his shoulders, we would run along in front of him, staring back at his not unkindly face. After Porter Rockwell died, some boys in the neighborhood thought it would be a good joke to haunt the big house where he had lived alone. One who worked in a drug store got some phosphorus, which we put on a sheet. We tied the sheet to a rope, and pulled it from the house to the barn. Breaking into the house, we rattled pieces of iron and crockery in an old keg, shook the windows and did other things to make a noise, so that one passing could not fail to notice the disturbance. The ghostly sheet and the continuous racket on dark nights gave the house the reputation of being haunted. All the boys who belonged to the gang were initiated with different hair-raising stunts.

The Sisters’ Academy of the Sacred Heart was in the next block. They had a little building adjoining the girls’ school where some small boys from the adjacent mining camps were boarded and given their first education. There were some day-scholars. Though not a Catholic, I was admitted to the school, where a nun called Sister Sylva was our teacher.

During vacation time my uncle Richard came to visit us from one of the nearby mining camps. Reading an advertisement one day in the paper that a boy was wanted on a farm, he talked it over with my mother, with the result that I was bound out to John Holden. For a period of six months at one dollar a month and board I was to be boy-of-all-work on the farm. There I milked two cows, fed the calves, cleaned out the stable, but my main job was driving a yoke of oxen.

One day I was in the field harrowing while Holden was plowing. A tooth of the harrow turned up a nest of field mice. They were curious little things. I had never seen the like before, and got down on my knees to examine them more closely. They were red, with no hair on their bodies. Their eyes were closed. The nest was a neat little home all lined with what seemed to be wool. It seemed only a few minutes that I looked at them, when all of a sudden I felt a smarting whiplash across my body. Holden had crossed the field, picked up the bull-whip I had dropped, and struck me without saying a word. I jumped up and ran straight to the house, gathered up my few belongings, tied them into a bundle and started for home. As I crossed the fields some distance from Holden I sang out: “Good-by, John!” I walked to the city some ten miles distant. This was my first strike.

When I got ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I-BOYHOOD AMONG THE MORMONS

- CHAPTER II-MINERS, COWBOYS AND INDIANS

- CHAPTER III-HOMESTEAD AND HARD TIMES

- CHAPTER IV-SILVER CITY

- CHAPTER V-THE WESTERN FEDERATION OF MINERS

- CHAPTER VI-TELLURIDE

- CHAPTER VII-TIN HOUSES AND AUTOCRACY

- CHAPTER VIII-CRIPPLE CREEK

- CHAPTER IX-IN THE CRUCIBLES OF COLORADO

- CHAPTER X-“DEPORTATION OR DEATH”

- CHAPTER XI-INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD

- CHAPTER XII-“UNDESIRABLE CITIZENS”

- CHAPTER XIII-THE BOISE TRIAL

- CHAPTER XIV-THE WORLD WIDENS

- CHAPTER XV-THE LAWRENCE STRIKE

- CHAPTER XVI-“ARTICLE 2, SECTION 6”

- CHAPTER XVII-THE PAGEANT

- CHAPTER XVIII-THE U.S. INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS COMMISSION

- CHAPTER XIX-RAIDS! RAIDS! RAIDS!

- CHAPTER XX-THE I.W.W. TRIALS

- CHAPTER XXI-THE PRISON

- CHAPTER XXII-WITH DROPS OF BLOOD

- CHAPTER XXIII-THE CENTRALIA TRAGEDY

- CHAPTER XXIV-FAREWELL, CAPITALIST AMERICA!

- CHAPTER XXV-HAYWOOD’S LIFE IN THE SOVIET UNION

- APPENDIX I - LIST OF I.W.W.’S CONVICTED IN THE SACRAMENTO CASE

- APPENDIX II - LIST OF I.W.W.’S CONVICTED IN THE WICHITA CASE

- APPENDIX III-LIST OF I.W.W.’S CONVICTED IN THE CHICAGO CASE

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER