- 552 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is Joseph Kinsey Howard's last major work. It describes for the first time in detail, the heroic struggle of a primitive people to establish their own empire in the heart of the North American continent.

Throughout his lifetime, Joseph Kinsey Howard was absorbed by the fateful dream of these American primitives, the Métis: their fathers, the English, the French, the Scots frontiersmen; their mothers the Native Americans.

"The compass of Strange Empire is the history of the resistance put up by people of mixed French and Indian blood and by their cousins, the Plains Indians, to the advance of the Canadian settlement frontier. Mr. Howard's narrative...is outstanding, not because he has offered much that hitherto was not known about the events, but because of his sensitive delineation of the cultures of the Plainsmen."—Douglas Kemp, The Beaver

"Mr. Howard's book...is history reflective of his humanity, as it is reflective of his integrity, his scholarship, his depth, his informed respect for language. It will endure as a contribution to historiography. "—A. B. Guthrie, Saturday Review

"The author has sacrificed neither fact nor detail in bringing to life events which hitherto have escaped the attention of most historians. Recommended."—J. E. Brown, Library Journal

"A moving and brooding book."—R. L. Neuberger, New York Times

"Vivid and absorbing. This book describes one of the crucial struggles in the long war for the west. It is sound and significant history, written with ardor and skill."—Walter Havighurst, Chicago Sunday Tribune

Throughout his lifetime, Joseph Kinsey Howard was absorbed by the fateful dream of these American primitives, the Métis: their fathers, the English, the French, the Scots frontiersmen; their mothers the Native Americans.

"The compass of Strange Empire is the history of the resistance put up by people of mixed French and Indian blood and by their cousins, the Plains Indians, to the advance of the Canadian settlement frontier. Mr. Howard's narrative...is outstanding, not because he has offered much that hitherto was not known about the events, but because of his sensitive delineation of the cultures of the Plainsmen."—Douglas Kemp, The Beaver

"Mr. Howard's book...is history reflective of his humanity, as it is reflective of his integrity, his scholarship, his depth, his informed respect for language. It will endure as a contribution to historiography. "—A. B. Guthrie, Saturday Review

"The author has sacrificed neither fact nor detail in bringing to life events which hitherto have escaped the attention of most historians. Recommended."—J. E. Brown, Library Journal

"A moving and brooding book."—R. L. Neuberger, New York Times

"Vivid and absorbing. This book describes one of the crucial struggles in the long war for the west. It is sound and significant history, written with ardor and skill."—Walter Havighurst, Chicago Sunday Tribune

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Strange Empire by Joseph Kinsey Howard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Amerikanische Bürgerkriegsgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

GeschichtePART ONE—Falcon’s Song

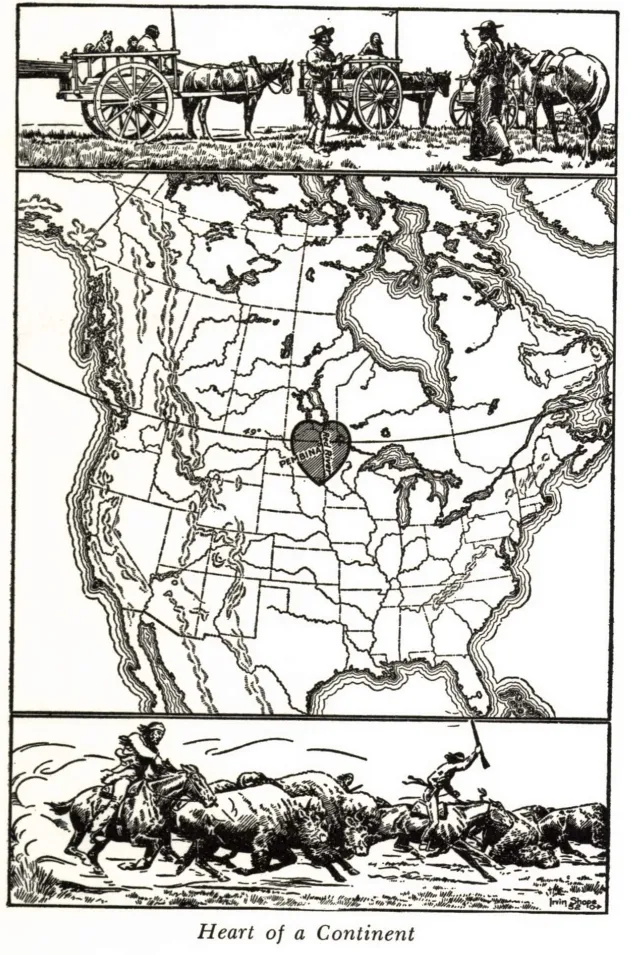

CHAPTER I—Heart of a Continent

GREAT LONE LAND

FROM the Red River of the North to the Rockies, winter ruled. In the winter the chepuyuk, the ghost dancers of the aurora, made a shuddering and swishing sound like that made by a throwing-stick when the boys played games on a windy day. It was customary for a man to shoot a few arrows toward the chepuyuk before closing the tipi flap for the night, to persuade them to keep their distance.

After a while the dancers gracefully withdrew and the strange sky-drumming which was the pulse of the universe grew faint. Then there was a little pause, and then came the wind. It was elemental force, homeless and heartless, rolling down from the far places, from the ice of Keewatin where the chepuyuk dwelt. The voice of Kichemanito was in it, reminding the man who had just knotted the tipi flap of his insignificance and his weakness. He shot off arrows to prove himself a man, a living thing and worthy of respect as were all living things (though no worthier than the living stone, or bird, or bison); but he knew always that nothing so puny as he could intimidate the mighty spirits he had been permitted to glimpse briefly as they trod their endless, stately measures into infinity.

Thus it was throughout the life of this man living in the buffalo-skin lodge which he had learned to design so that it would fend off the icy surf of the wind. First the drumming, then a little rest while the gods gathered their strength, then the gale; and finally the night swept clean. Then the man could put aside the tent flap and come outside to look, to stand erect but humble in a frozen instant of endless time, taking peace to himself from the sudden quiet, seeing the fixed glitter in the limitless sea of snow, seeing the sky full of stars and mystery come down over the smoke hole of his lodge.

The man, a Cree Indian, lived in the heart of the North American continent, the great basin of the Red River of the North. It extends from the river’s source in south-central Minnesota, near the South Dakota border, north 545 miles to Lake Winnipeg. The river valley, once the bed of glacial Lake Agassiz, is ten to a hundred miles wide. At its western edge, elevated three hundred feet above the river channel, lies a glacial drift prairie which reaches two hundred miles west to the Missouri River Plateau.

Instinct drew the Indian here, as it was to draw many others, even white men, after him; for this vast, well-watered, almost treeless basin and the neighboring plain were rich in resources to support man. The soil, a black loam four to twelve inches deep, produced hardy, succulent grasses upon which fed millions of buffalo. There were many rivers, and where there are rivers there are furs. In fact, water was sometimes too plentiful: there were, and still are, floods thirty miles wide.

Here three great river basins joined: the Nelson, draining north to Hudson’s Bay; the St. Lawrence, tumbling eastward to the Atlantic, and the mighty Mississippi rolling slowly southward to the Gulf. And only a little way to the west, across a ridge so low that travelers scarcely noticed it, lay the country of the Upper Missouri, full of furs and buffalo, too.

Today two of these rivers are Canadian, two are in the United States. But rivers, as Pascal said, are roads which move; they do not pause at customhouses. Nor did the men who lived by them and moved on them. The forty-ninth parallel, cutting east to west through the heart of the basin and the plain, was a conceit of congressmen, not of ecologists. It could not arrest the movement of men and ideas any more effectively than it could that of the buffalo herds.

This was the West, the last frontier, the country of contrast and conflict. Here for decades there was to be drama born of incessant struggle between men of irreconcilable races, faiths, and political principles, and between these men and Nature. Here there was to be political pandemonium of a type Americans are wont to attribute contemptuously to Europe’s Balkan States, and religious and racial wars like those which reddened the sands of Africa.

Each of the four rivers which brought men to this crossroads of the continent brought also the political and cultural formulas by which the men were determined to live. And even in a basin of two million acres there was not room for any two of these systems to dwell together in peace.

The first river to contribute was the St. Lawrence, and the men it brought were French. Pierre Radisson may have entered the Red River country from the Great Lakes in 1659, but if he did so he immediately rejoined his partner Groseilliers at Lake Superior. French voyageurs, their names now unknown, reached Lake Winnipeg soon after the beginning of the next century, but the first white man to “stake a claim” on behalf of his race was the intrepid explorer-trader De la Vérendrye. He established Fort Rouge at the Forks of the Red River (the mouth of the Assiniboine) in 1738, and placed another, his headquarters, a short distance to the west. The city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, which has about a quarter of a million people, now stands at the Forks, and the site of the other post is occupied by the town of Portage la Prairie. They are the oldest communities established by white men in the Northwest.

Over the St. Lawrence canoe route the French brought their mystic piety, their thirst for adventure and for knowledge of what lay beyond the next hill, and a talent for military organization. They were almost free of racial arrogance, sincerely devoted to a faith which proclaimed all men equal in the sight of God but which demanded that every footloose Frenchman should be an instrument for conversion of the pagans of the New World. They were quite willing to marry in the Indian camps. It is small wonder that they were the most admirable of the newcomers in the eyes of the Indians, for their qualities were those which, in tribal tradition, made virile races.

Down from Hudson’s Bay—but up the northward-flowing rivers—came the English and the Scotch, the meticulous merchants. They were proud of their white skin and their spotless linen and their heirloom china, arrogant and authoritarian, inflexible of faith, scornful of horizon-hunting when there was money to be made near at hand. And they were bred to firm dealing with “subject races.” They were not very popular on the Western frontier a century ago, and—until acclimatized—they are not very popular yet; but they blundered through to victory in the War for the West. Dogged, the British.

The Mississippi contributed a new people, confident of their Manifest Destiny after they had survived a bloody Civil War. The Americans were money men like the British, but they were willing to gamble as the British were not, and they were determined to build an empire—whereas the British already had an empire which they were beginning to find a little tiresome. These men from the south whom the Indians called the Long-Knives were as certain as Americans have always been that their political system was divinely ordained, beyond criticism, and adaptable to all places and peoples. The Indians tolerated them, used them, and, on occasion, slaughtered them. The Americans never won the affection the aborigines freely gave the French or the tribute of fear and respect which they grudgingly accorded to the British.

Across the low divide to the west were the mountain men, the hunters and trappers of the Upper Missouri, closely associated with the Red River people and sharing their interests. Most of them were technically Americans, too; but they were fugitives from the newborn boosterism of the Mississippi Valley and from the political and social restraints which their compatriots to the east were busily fashioning. The big sky, the far horizon, drew them as it did the French; the hardships encountered in their seeking taught them respect for the elements and for elemental gods; and in their loneliness they learned to esteem the Indian wives they took “after the custom of the country.” For the most part they got along well with their Red River neighbors and perhaps could have dwelt happily among them but for the fact that they could not abide a land which was so damnably flat.

Here in the heart of North America history moved south. The Indians came from Asia, across the land bridge which now is Bering Strait, and south on the long hungry trail through the Barren Lands. The men who ultimately were to conquer them came also from the north, from Hudson’s Bay through the brush country to the Forks, and beyond to the open buffalo plains.

There, on the shores of the sea of grass, these men from the north and those from the St. Lawrence built a town which they called Pembina. The name, originally Pambian, was a French rendering of a Cree-Chippewa term for the high-bush cranberry, but it also meant “sanctified bread” because the berries were used in pemmican which was blessed by the priest.

Pembina still exists as a sleepy border village in North Dakota. It was an inhabited place in 1780 and thus is the oldest community in the American Northwest. But it has been neglected in all save the local histories, and somewhat neglected even there because so much has happened that not even the oldest residents could ever recall it all.

Few Pembina residents ever knew, for instance, that the first white children in the American or Canadian Northwest were born there. There were two, born in the same week; the parents of one came from Hudson’s Bay, those of the other entered the country by the St. Lawrence. And Americans may find it odd that this American town was the first prairie headquarters of the thoroughly British Hudson’s Bay Company, that it once was owned by a Scottish earl, and that it once was peopled almost entirely by German and Swiss mercenaries, veterans of some dog-eared European war.

But those distinctions are less important to us than some others. Pembina, a log-cabin village, was the first capital of a new race, the Métis or Red River half-breeds of the North-west—in so far as a people who always shunned settlements could be said to have had a capital. It was the principal seat of their church, established in 1818 and served by a bishop whose diocesan boundaries (ignoring such political fictions as the forty-ninth parallel) were officially the Great Lakes, the North Pole, and the Pacific.

And, only eighty years ago, this village of Pembina was the scene of a political tragicomedy which determined the sovereignty of British North America and cost the United States its chance to acquire half a continent.

The map in Morse’s Geography, a school text in the United States from its publication in 1789 until about 1812, labeled the country west of Lake Michigan as “little known,” which indeed it was. But blank spots on maps are quickly filled by legend, and the mysterious mid-continent has always lent itself to wild tales.

There were, for instance, the “Welsh Indians” who dwelt just over the ridge, on the Missouri. They were the Mandans, and no more Welsh than were the Eskimos; but because, for Indians, they were light in color, lived in mud-and-brush huts instead of skin lodges, tended gardens, and spoke a strange tongue, they were reputed to be the descendants of Welsh colonists brought to America by the fabled Prince Madoc in the twelfth century. Vérendrye found the Mandans in 1738 and Lewis and Clark wintered among them in 1804-5; like all competent observers they reported that they were just Indians, though a friendly bunch. (Perhaps too friendly; the tribe is now extinct.) But the legend of Madoc persisted and crops up occasionally even now.

Another story, of more recent origin, may have greater validity. In 1898 a farmer living at Kensington, Minnesota, on the eastern edge of the Red River Basin, discovered an inscribed stone in the roots of an aspen tree. This, the famous Kensington Stone, has now been tentatively accepted by the Smithsonian Institution as authentic to the extent that the runes, the characters in which the inscription is composed, appear to date from the fourteenth century. The stone purports to give an account, written by a survivor, of the massacre of a group of Norse explorers by Indians at this site in 1362.

Supporters of the “Vinland” theory—that Norsemen visited North America in the eleventh and fourteenth centuries—hold that this stone and more than a dozen other relics such as swords, axes and mooring stones for boats, prove that the Vikings penetrated the interior of the continent more than a century before Columbus sighted San Salvador. Most of these relics have been found in the Red River Valley.

The tales have significance here only because of the locale. Obviously, civilized man has found it incredible that such a bounteous empire as the northern mid-continent basin should have been uninhabited save by “savages” until Vérendrye’s posts were established in the eighteenth century. Such neglect reflects somehow upon the white man’s intelligence and initiative.

The crossroads of the continent needs no myth; its recorded history is romantic enough.

That history opens with the issuance of a charter, in 1670, by Charles II to “The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay.” The Governor was Prince Rupert, cousin of the King, and the charter made the Company “true and absolute lords and proprietors” of all the lands drained by rivers entering the Bay. That domain—a third of a million square miles, though no one knew its extent then—was named Rupert’s Land. Some of it lay south of the forty-ninth parallel, in what are now the states of Minnesota, North Dakota, and Montana.

But the “Adventurers of England” were incurious and unenterprising and their employees were timid. Only one, “the boy Henry Kelsey” who actually was a youth of twenty, could be induced to strike out from the Company’s posts on the Bay into the prairie wilderness. Accompanied by an Indian, he went into the Assiniboine country, from Lake Winnipeg perhaps to what is now eastern Saskatchewan, in 1690, and spent almost two years. He was apparently the first white man to see musk oxen. Nearly a century passed before the Company, spurred by competition, established...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- MAPS BY IRVIN SHOPE

- JOSEPH KINSEY HOWARD

- INTRODUCTION-One Sure and Certain Loyalty

- PART ONE-Falcon’s Song

- PART TWO-New Nation

- PART THREE-Crackpot Crusade

- PART FOUR-Decade of Death

- PART FIVE-Path of Providence

- PART SIX-Prophet on Horseback

- PART SEVEN-Cardboard Shrine

- PART EIGHT-High Treason

- Bibliography-Compiled by ROSALEA FOX

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER