eBook - ePub

Detroit's Birwood Wall

Hatred & Healing in the West Eight Mile Community

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 1941, a real estate developer in northwest Detroit faced a dilemma. He needed federal financing for white clients purchasing lots in a new subdivision abutting a community of mostly African Americans. When the banks deemed the development too risky because of potential racial tension, the developer proposed a novel solution. He built a six-foot-tall, one-foot-thick concrete barrier extending from Eight Mile Road south for three city blocks--the infamous Birwood Wall. It changed life in West Eight Mile forever. Gathering personal interviews, family histories, land records and other archival sources, author Gerald Van Dusen tells the story of this isolated black enclave that persevered through all manner of racial barriers and transformed a symbol of discrimination into an expression of hope and perseverance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Detroit's Birwood Wall by Gerald Van Dusen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Discrimination & Race Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

THE CONTOURS OF THE ENCLAVE

By the end of World War I, the community along Eight Mile Road, though small, had become well established. Its stability was based not on the number of families, the years in residence or even on the physical proximity of one neighbor to another; rather, it was based on the many relationships formed by common needs and interests. Joint activities—sharing homebuilding skills, establishing a local church, cultivating a garden, supporting local black-owned businesses, serving on school committees or simply celebrating the birth of a baby or a wedding—strengthened existing bonds and helped the community confront barriers placed in its path by external entities. In the coming years, various physical, legal and social barriers—the Birwood Wall, Slatkin’s fence, restrictive covenants, segregated schools and lack of access to public accommodation—would further isolate and threaten to sap the vitality of this growing community. However, as Dr. Mark Hyman suggested, “The power of community to create health is far greater than any physician, clinic, or hospital.”30 Whether fully conscious of its power to heal or not, the African American enclave remained vital and resilient through self-reliance and a pioneering spirit.

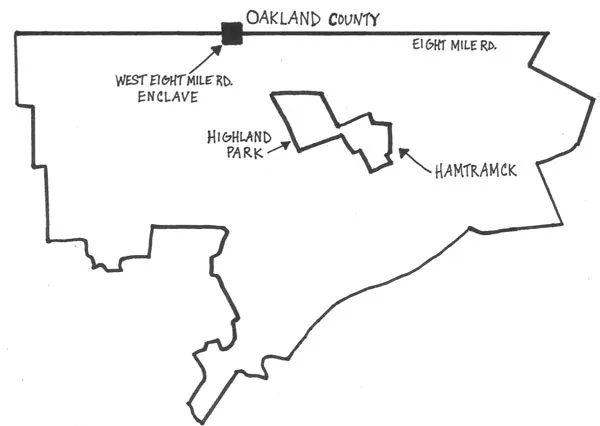

Eight Mile Road runs along the surveyor’s baseline that established the borders of Michigan’s township system during the nineteenth century. In metropolitan Detroit, the baseline served to separate the original thirty-sixsquare-mile Royal Oak Township in Oakland County to the north from Greenfield Township in Wayne County to the south of the baseline. In a sense, the West Eight Mile community can only be fully understood as two halves of a larger one-square-mile whole, the present half-square-mile Royal Oak Township north of Eight Mile and the half-square-mile African American neighborhoods to the south. Although both communities have unique historical moments, they are aligned closely by race, by culture and by shared experiences.

Ink drawing of Detroit boundaries, 1941. Lauren Gohl.

THE ORIGINS OF MODERN ROYAL OAK TOWNSHIP

Royal Oak Township wasn’t always a hamlet and wasn’t always African American. Its history follows a complex path to the present day. Under the ordinance of 1785, the federal government proclaimed civil townships, each thirty-six square miles, as the basic unit of land management. The area directly north of today’s West Eight Mile was described in an 1817 survey as “irreclaimable, and must remain forever unfit for culture or occupation, and must remain in the possession of wild beasts.”31 On December 5, 1819, General Lewis Cass, the governor of the Michigan territory, set out to explore this forbidding territory on his way to sign a treaty with the Saginaw Indians. At a certain point, the governor was forced to leave behind his horse and slog through marshland with his party on foot. Upon approaching an old Ottawa Indian trail (Woodward Avenue), he established a road, which he marked as H, twelve miles north of Detroit, and paused to rest on solid ground under an oak tree. The governor was inspired to call the tree a Royal Oak, a conscious allusion to the legend of the original Royal Oak, located at Boscobel in Shropshire, England. In 1650, King Charles II hid in an old oak tree to elude the pursuit of Oliver Cromwell’s men during the English Civil War. The tree became immortalized as the “Royal Oak” after Charles was able to regain the throne of England in 1660.

An act of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Michigan in 1832, which described the area as being located near an oak tree where Governor Cass and his party were to have rested, proclaimed it Royal Oak Township. The original oak tree, located at what is now the triangular intersection of Main, Rochester and Crooks Roads, was cut down in 1853. In June 1917, the Royal Oak Women’s Club erected a marker that is now located at the entrance to Oakview Cemetery on Rochester Road.32 The marker reads,

Royal Oak memorial marker, Royal Oak, Michigan. Author’s collection.

“Near this spot stood the oak tree named by Governor Cass, the ‘Royal Oak’ from which Royal Oak Township received its name.”

By this time, large numbers of migrants from the rural South had begun steadily arriving in the Detroit area in search of work and in response to deteriorating racial conditions in the former Confederate states. Most were directed to the segregated, working-class neighborhoods of Detroit’s lower east side, but a few managed to bypass the overcrowded side streets of Black Bottom and settle north of the city in the unincorporated area around Eight Mile and Wyoming Roads. This was a remote area lacking city services, but because of housing restrictions within the city, there were few other choices where to live.

Both sides of rural Eight Mile Road became recognized as areas of black settlement. North of Eight Mile, the designated land was defined as Eight Mile, Detroyal, Forest Grove and Wyoming Park. Today, it is known as Eight Mile, Northend, Meyers Road and Mitcheldale. The area settled by African Americans was well known for its infestation of snakes, rabbits, skunks, hedgehogs, chipmunks, mud and slush, cranberry swamps and heavy forestation.

The thirty-six-square-mile township began to shrink beginning in 1921 with the incorporation of Berkley, Clawson, Royal Oak (the city), Hazel Park, Ferndale, Oak Park, Madison Heights, Pleasant Ridge and Huntington Woods. What remained of the original Royal Oak Township were two distinct, noncontiguous entities, one almost exclusively African American along Eight Mile Road and one to the north along Ten Mile Road. Much later, the northern tier of Royal Oak Township developed gradually into a largely middle-class area with a substantial Jewish settlement within its total population of 2,800 according to the 2000 U.S. Census. In 2004, this now largely ethnic Jewish community was annexed by Oak Park. During this entire period of incorporation, the African American area remained unwanted, unannexed and unincorporated.

World War II brought with it another surge of southern migration to Detroit. Nearly two thousand African Americans were moving into the Detroit area each month seeking war-related work, but few areas within highly segregated Detroit were capable of housing this tremendous influx. Agencies such as the FHA and Federal Public Housing Authority (FPHA) scrambled to find suitable locations for the construction of public and private housing specifically targeted for black war workers. The race riot of 1943 provided further impetus to the search, and soon the Eight Mile and Wyoming area in northwest Detroit came under considerable scrutiny.

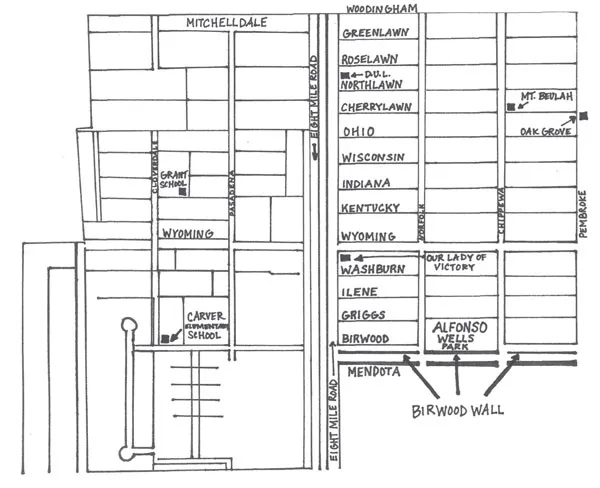

Ink drawing of West Eight Mile enclave. Lauren Gohl.

Both the Detroit Housing Commission and the City Planning Commission had already taken the position that the area could be used for temporary war housing as part of a larger postwar redevelopment plan. However, with the FHA now approving single-family home construction to the east of the Birwood Wall, only a few hundred temporary war housing units could be constructed.33

With fewer war housing units than anticipated slated for construction on the Detroit side of Eight Mile Road, attention focused on the area north along Wyoming Avenue in Royal Oak Township. The FPHA determined that sufficient vacant land was available for the construction of nearly 1,500 temporary war housing units, and construction soon began.34 The large population of African Americans now living in purportedly “temporary” wartime housing in southern Oakland County would pose unanticipated issues in the years ahead for the neighboring communities of Ferndale and Oak Park and thrust them onto the national stage.

Chapter 2

HOUSING BARRIERS

Today, a casual walk down Mendota, the street on the other side of the Birwood Wall, brings into view a handful of abandoned, gutted structures among the otherwise well-kept brick bungalows that line both sides south to Pembroke Avenue. The formal abolition of restrictive covenant enforcement in 1948 gradually brought about the breakdown of the color line established by the Birwood Wall, and blacks have been buying properties on both sides of the wall since the early 1950s. Blockbusting and the threat of school busing frightened enough white home owners to sell during a wave of white flight. As Saul Alinsky cynically observed, “A racially integrated community is a chronological term timed from the entrance of the first black family to the exit of the last white family.” After the 1967 racial rebellion, the timing accelerated dramatically.

When the Birwood Wall was constructed in 1941, Detroit’s housing crisis had already reached the city’s outskirts. In the immediate neighborhoods to the east and south of the West Eight Mile community, housing had reached near maximum density. To the west, the new whites-only subdivision was being platted. The frustrations and fears of hundreds of residents of the African American community were finding a voice in the outspoken leaders of both the Carver Progressive Club and Eight Mile Road Civic Association. The construction of the Birwood Wall had made clear that the FHA was not interested in making any significant breakthroughs with respect to racial integration. But perhaps the two neighborhood associations could broker a deal with the federal authorities whereby some relief, in the form of FHAbacked mortgage loans, could remedy the deteriorating housing conditions in the forty-two-square-block area that the HOLC’s residential security maps had outlined in red.

THE STORY OF A SUBURBAN SLUM

This optimistic vision for the community by its associations’ leaders met formidable opposition by a number of reform-minded organizations that had very different visions and agendas for the area. Chief among these was the Citizens’ Housing and Planning Council of Detroit (CHPC), with its offices in the 1928 Art Deco masterpiece the Penobscot Building in downtown Detroit. In 1939, white sociologist Marvel Daines was dispatched to the area to report on social, economic and physical conditions.

Her report, entitled “Be It Ever So Tumbled: The Story of a Suburban Slum,” describes the settlement as little more than “shacks of the most miserable character—unpainted, dilapidated, and in many cases practically in ruins.” A brief history of the area that followed suggests that the black pioneers who settled the area, having migrated from the South with little money and less knowledge of construction requirements for a cold northern climate, built these flimsy domiciles with little outside assistance and, in the main, with sweat equity. Even before the author presents statistical data that is at the heart of the report, she cannot help but reveal her condescending attitude toward the residents of the area by recording all conversations in the exaggerated patois of uneducated southern blacks. One resident is quoted explaining why construction was so inadequate: “It done took four yeahs to get da house up, ’count we hadda pay fifteen hundr’d dollahs fo’ de naked lan’, an’ we didn’ have nothin’ lef ’ fo’ de lumbah.”35

Despite the paternalistic tone that permeates the fifty-two-page pamphlet, the statistical data presented offer a window into the conditions in which residents were living. For example, of the 1,781 parcels of land that make up the Eight Mile–Wyoming area, 1,287, or 72 percent, were still vacant. More than 90 percent of existing structures were detached single-family units, of which 60 percent were built before 1924. Only 16 percent of these homes were in good condition, with three in ten requiring major repair. Fewer than half of the dwellings had a toilet and bath. Given the overall condition, seven in ten homes were rated “substandard” by the Real Property Inventory and Housing Survey, completed in 1938 by the Detroit Housing Commission.36

The interview portion of the report was intended to reveal the “human side” of the community, a side that naked statistics were not likely to reveal. The strategy was simple. Daines would interview the adult occupants of every tenth house in the forty-two-block area bounded by Eight Mile to the north, Woodingham Drive to the east, Pembroke to the south and Birwood to the west. Since there were 469 families living in the area, 48 would be contacted. With 10 percent of the residents interviewed, certain conclusions could be extrapolated.

The intent of the interviews, as expressed in the report’s introduction, was to answer variations of the same question: “Why don’t they keep their homes in better condition?” and “Why have they let them run down until they are an eyesore to the surrounding neighborhoods?” The logical fallacy of the questions, of course, is that they include the presumption of guilt and, ultimately, serve the author’s (and agency’s) agenda. To this end, Daines requested of each homeowner specific information regarding sources, types and amounts of income; number and kinds of automobiles owned; and personal characteristics such as hobbies and church affiliations:

It is amazing to see how far a factory wage can go—how many dozen pairs of shoes it can buy a year, how many growing young bodies it can clothe, how many hungry little mouths it can feed.

“I have to scrimp each month to make ends meet,” Mrs. Appleton told me. “But these young ones are worth all the hours I spend making their clothes and figuring out how to buy the things they need.”

Mr. Appleton works in a factory and earns $30 a week. They are an intelligent couple and are proud of their children. They have reason to be—. The children were at home eating their lunch when I visited. One goes to school and the other four range from one to six years of age. They are extremely attractive children—wide-eyed, well-mannered, spotlessly dressed. Their home is of the better type, with plastered walls nicely decorated, a furnace, bath, and modern kitchen. The furnishings are attractive and in excellent taste.

“We know we shouldn’t be paying $30 a month rent on our income,” Mrs. Appleton admitted to me, “but we did want a decent place for the children. We like it here—it’s a nice neighborhood—but it keeps me busy figuring out how to give them all the other things I want them to have.”37

Daines’s conclusion was one of simple economics: the City of Detroit can no longer afford to subsidize the slum that the West Eight Mile community had become, especially given its history of delinquent or unpaid property taxes; the high cost of educating 386 black children at Higginbotham School; operating Birdhurst Recreation Cent...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword, by Reverend Jim Holley, PhD

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Contours of the Enclave

- 2. Housing Barriers

- 3. Barriers to Employment

- 4. Barriers to Education

- 5. Barriers to Transportation

- 6. Barriers to Healthcare

- 7. Barriers to Public Accommodations

- Conclusion. From Sweat Equity to Racial Justice

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author