- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author documents the political history of federal corn ethanol policy, showing how it has evolved from 1977 through 2008. He then offers an in-depth, fact-based look at the major assertions made by the advocates of the policy, providing the results of an evaluation of the claims made by the architects of the Renewal Fuels Standard in 2005 during its consideration by Congress.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Corn Ethanol by Ken G. Glozer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Political History & TheoryPART I

Political History

1

Introduction

This book has a twofold purpose. The first part is devoted to documenting the political history of federal ethanol policy and showing how it has evolved from 1977 through early 2009. Part I attempts to answer important questions about when the policy started, how it evolved, what the major political and market forces were that drove it, and, most importantly, which officials shaped it.

The second part of the book evaluates the major claims made by the policy’s advocates over a thirty-year period. It assesses the following questions:

- Will the policy significantly reduce U.S. petroleum imports and increase energy security?

- Does using corn ethanol as a transportation fuel improve the environment?

- How sound are other frequent claims, including whether the policy reduces federal budget costs, reduces the U.S. balance of payments deficit, or increases rural employment?

- Who pays for the policy, and who benefits from it?

All of that is important because the federal agencies involved (Environmental Protection Agency and the Departments of Energy and Agriculture—hereafter EPA, the DoE, and the DoA, respectively) have become promoters of the policy, along with such private advocacy groups as the Renewable Fuels Association, National Corn Growers Association, and Clean Fuels Association. They and others have made claims about the tremendous benefits bestowed on consumers and taxpayers in the process of securing enactment of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007.

Those Acts contained the Renewable Fuels Standard, which requires petroleum refiners and importers to blend 15 billion gallons of ethanol annually in gasoline by 2015. That incentive supplements the tax credit of 45 cents per gallon of ethanol blended into gasoline and the import fee on ethanol imports of 54 cents per gallon. The latter two policies have existed since the early 1980s.

2

Ethanol as a Transportation Fuel

How Federal Corn-Ethanol Policy Evolved

Introduction

Ethanol, also called ethyl alcohol, is a pure form of alcohol that has been used as an automotive fuel since the first days of the automobile. Ethanol can be made by fermenting sugars (Brazil) or in the case of corn (U.S.), converting corn starch into sugar, then fermenting the sugars into ethanol. Ethanol can be made from other crops such as sorghum and other feed stocks, such as switchgrass, corn, and rice stalks. The latter process requires more processing steps and is referred to as cellulosic ethanol.

Ethanol is a high-octane fuel. Henry Ford championed it as an automotive fuel, and his Model T was designed to run on either pure ethanol or gasoline. Ethanol competed with gasoline in the 1920s and ’30s in the United States, but eventually lost the battle as automotive-fuel consumption increased and major oil discoveries were made that provided the volume of fuel needed at very competitive prices. It reappeared briefly during the fuel shortages of World War II, but did not appear in consumer markets until the energy crises of the 1970s, prompted by incentives from state and federal governments. The incentives were aimed at growing the biomass, building the distilleries, and selling the final product, and to do that they made use of an extensive array of income supports, government research, tax breaks, loans, and outright mandates for use. Ethanol was not again produced in volume for automotive use until the 1970s.

Starting from a base of virtually no commercial sales in the mid-1970s, ethanol has grown to a point where it now accounts for over 6 percent (by volume) of U.S. gasoline sales. And current legislation mandates further increases that could take ethanol beyond 10 percent of sales by 2010. Today, virtually all ethanol comes from corn and sorghum in a distillation process that first isolates a sugar-rich byproduct from the production of corn syrup and animal feed, ferments the byproduct, and distills the pure alcohol from the fermented biomass. Distillation of ethanol for fuel is the same process used to produce alcohol for consumer beverages. Nowadays, almost all gasoline sold contains low concentrations of ethanol, but about 6 million vehicles (out of 230 million) on the road are capable of running on E85 gasohol—a blend of gasoline with up to 85 percent ethanol.

The first significant market for ethanol emerged mainly in the corn-growing states of the Midwest, where gasoline was blended with 10 percent ethanol to produce a fuel known as gasohol. The original rationale for federal support for ethanol was to help boost farm incomes, and that became linked to a desire to reduce dependence on crude oil imports. The many federal programs that support the industry acted to create a demand for the fuel, artificially lower its production costs, eliminate competition, and remove environmental regulations that restricted its production and use.

Three phases in the growth of the industry stand out. The first significant federal program to promote ethanol was the exemption—in 1978—of ethanol blends from a portion of the federal motor-fuel taxes. Combined with state tax exemptions, that made the fuel marginally competitive with gasoline in the Midwest and jump-started the market. Early federal programs to provide tariff protection against low-cost ethanol imports (produced from sugar cane in Latin America), financial incentives for ethanol plant investment and production, mandates for government purchases of alternative-fuel vehicles, and government research and developments spending also helped to develop the industry.

Then, in the 1990s, the rationale for ethanol support expanded to include clean air. For the first time, clean air legislation mandated the formulation of gasoline to create a new market for ethanol as an environmental blending agent—or oxygenate—to help reduce carbon monoxide emissions. Most of that oxygenates market was claimed by the compound MTBE (methyl tertiary butyl ether), which also helped to boost gasoline octane rating. However, when a growing number of state-level bans on MTBE use took effect, around 2000, the market for ethanol as a major octane enhancer began to increase.

Third, the most recent federal legislative action, in 2007, pushed ethanol as a panacea for global warming and U.S. energy security by mandating five-fold increases in the amount of fuel blended with gasoline, to 15 billion gallons annually by 2015. Those levels go well beyond limits for ethanol as an octane enhancer in a slowly growing gasoline market, and they could only be met if ethanol were marketed in concentrations well above the 10-percent level, perhaps going all the way to E85 gasohol in some regions.

Throughout that history, political activities of the groups representing corn producers and ethanol producers have been critical to the industry’s development. The early advocates of the fuel adroitly used the national political process at key points to build a highly influential and effective lobby that today dominates the legislative process in Washington. In the early years, the lobby was dominated by the interests of the corn states, which were facing new competition abroad, excess production at home, and falling prices. Those corn interests included the newly emerging industry of corn syrup manufacturers (in particular, Archer Daniels Midland) with excess feedstock that could be made available for fermentation and alcohol production. All presidents have recognized the political importance of the farm states.

As a result, the DoE and DoA, as well as the EPA, have consistently supported the expansion of corn ethanol production.

The ethanol lobby had the backing of several groups, starting with policymakers who were looking at any and all technologies that could help protect the nation from oil-supply disruptions. Together those interests helped to secure the first federal-tax subsidy for ethanol and, by 1980, tariff protection as well. In 1988, the lobby added domestic automakers to the fold by crafting an arbitrary and generous CAFE (corporate average fuel economy) benefit for the production of “flexible-fuel” vehicles capable of burning E85 gasohol.

Early environmental support for ethanol had always been mixed. Advocates also pointed to the benefits of using it to lower vehicle emissions of carbon monoxide, and they worked to weaken government restrictions on gasoline vapor pressure—put in place to check other harmful emissions of ozone precursors and carcinogens—to boost the market for ethanol blending. But the growing concern with global warming in the past decade had the effect of pulling environmental interests strongly behind the most recent push to craft a strong renewable-fuels standard for the country.

Taken together, the power of such political concerns as energy security and a healthy environment, the critical placement of agricultural interests in federal politics, and the effectiveness of corn and ethanol lobbying have combined to produce several major—and many minor—political successes for ethanol. Among the most noteworthy policy developments of the past three decades are these:

- Exemptions of ethanol sales from federal taxes on motor fuels and a tariff on imported ethanol, first authorized under the Carter administration;

- Billions of dollars authorized for federal loans and loan guarantees for ethanol plant construction, greatly expanded in the Carter administration but mostly rescinded under Reagan;

- Credits against fuel economy standards for automakers that produce vehicles capable of burning E85 gasohol (even if they seldom actually do), authorized during the Reagan administration;

- Mandates for the use of ethanol (and other oxygenated fuels such as MTBE) in reformulated gasoline, authorized under the first Bush administration;

- State-level bans on MTBE, starting under Clinton, which boosted demand for ethanol in reformulated gasoline and created a new market for ethanol as an octane enhancer;

- Renewable fuels standards, authorized under the second Bush administration, that require annual quantities of ethanol to be blended into gasoline far in excess of octane needs—including 15 billion gallons of ethanol from corn and 21 billion gallons from cellulosic and other biomass sources.

But clouds have gathered on the horizon, as a world food shortage and record prices for grains emerge and some countries halt their corn ethanol program. Further, recent research has disclosed that corn-based ethanol may substantially increase greenhouse gas emissions, if indirect land-use impacts of forest or grassland conversions into cropland are properly taken into account. And even with ethanol prices rising sharply along with gasoline, corn prices rose even more quickly in 2008 (to over $6 a bushel in future’s markets). That squeeze is greatly undermining the profitability of ethanol production. And in 2008 and 2009, the sharp, dramatic decline in oil and ethanol prices forced a number of ethanol producers into bankruptcy.

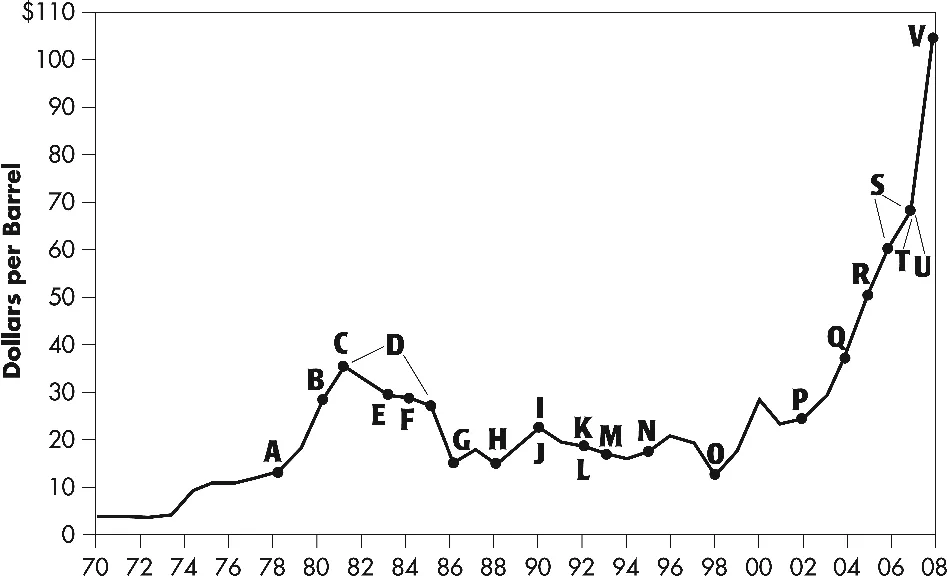

The following sections document the federal policy history of corn ethanol from the Carter administration through that of George W. Bush, describing the significant legislative and administrative building blocks and the evolution of today’s ethanol policy. Included in this part are three important figures. Figure 2.1 displays crude oil prices year by year from 1970 through 2008, with each of the major federal ethanol policy interventions identified in the given year. Figure 2.2 displays U.S. corn production and prices year by year from 1970 through 2008, noting the years when weather had a major and adverse impact on corn production. Figure 2.3 displays year by year, from 1975 through 2008, annual U.S. petroleum imports and domestic ethanol production.

A. Carter Administration—Jump Starting a New Industry with Tax Incentives, Tariffs, and Financial Support

Summary

The decade of the 1970s saw sharply rising oil prices and outright shortages of gasoline supply, precipitated by the Arab oil embargo of 1973–74 (see Figure 2.1). Those problems were exacerbated by the federal system of crude-oil price controls and petroleum-product price and allocation controls, first imposed by the Nixon administration in 1971. Domestic events unrelated to the oil embargo also were disrupting markets for coal and natural gas. Subsequent reductions in world oil supplies, following the Iranian Revolution and related events in 1979 and 1980, combined with the partial controls over crude oil and gasoline prices still in place to further roil energy markets. Policy makers desperately sought new and reliable domestic supplies of energy—especially gasoline—and the advocates of corn ethanol took advantage of that situation.

Figure 2.1 Crude Oil Prices 1970 to 2008

Source: Department of Energy (DoE)/Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Legend for Figure 2.1

| A | 1978 | A 40-cent-per-gallon ethanol gasoline-tax exemption enacted. |

| B | 1980 | A 40-cent-per-gallon tariff on imported ethanol and a new federal loan-guarantee program for ethanol plant construction enacted. |

| C | 1981 | President Reagan abolished petroleum allocation and price controls, and established a competitive market-reliance policy for petroleum. |

| D | 1981 to 1985 | Phase-out of federal loan-guarantee assistance for ethanol plant construction. |

| E | 1983 | Ethanol gasoline tax exemption raised to 50 cents per gallon. |

| F | 1984 | Ethanol gasoline tax exemption raised to 60 cents per gallon and tariff on imported ethanol increased to 60 cents per gallon. |

| G | 1986 | Department of Agriculture (DoA) provided free corn to ethanol plant operators. |

| H | 1988 | Domestic auto manufacturers receive special Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) mileage credit of 6.7 times vehicle’s actual Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-mileage rating if vehicle capable of burning 85 percent ethanol/15 percent gasoline blend. Vehicles able to do that became known as FFVs (flexible-fuel vehicles). |

| I | 1990 | Clean Air Act Amendments enacted, requiring oxygenated gasoline in metropolitan areas not in compliance with the EPA’s carbon-monoxide air standards. |

| J | 1990 | Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 reduced ethanol gasoline-tax exemption to 54 cents per gallon and extended it to 2000. |

| K | 1992 | Energy Policy Act of 1992 included major ethanol subsidies: a $2,000 deduction for alternative-fuel vehicles, including FFVs; a $100,000 deduction for retail fueling stations that installed pumps for alternative fuels, including E85 ethanol. |

| L | 1992 | President Bush directed the EPA to change vapor pressure (RVP) to a higher level sought by ethanol advocates, even though doing so increased auto emissions and metropolitan-area pollution. |

| M | 1993 | President Clinton rescinded Bush’s higher RVP regulation but required that 30 percent of the oxygenate blend be ethanol. |

| N | 1995 | The courts overturned Clinton’s 1993 ethanol requirement. |

| O | 1998 | Ethanol gasoline tax-exemption phased back to 51 cents per gallon by 2005 and extended to 2007. |

| P | 2002 | Farm bill enacted, providing cash payments to ethanol producers. |

| Q | 2004 | Ethanol gasoline-tax exemption, whose cost was borne by the Highway Trust Fund, converted to a tax credit reducing U.S. Treasury General Fund Tax revenues. |

| R | 2005 | Energy Policy Act of 2005 established the Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS), mandating ethanol blending with gasoline of 7.5 billion gallons by 2012. Also, the ... |

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I Political History

- Part II Evaluating Advocates’ Policy Claims

- Part III Supporting Documents

- Endnotes

- About the Author

- Index