- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Flat Tax

About this book

This new and updated edition of The Flat Tax—called "the bible of the flat tax movement" by Forbes—explains what's wrong with our present tax system and offers a practical alternative. Hall and Rabushka set forth what many believe is the most fair, efficient, simple, and workable tax reform plan on the table: tax all income, once only, at a uniform rate of 19 percent.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. Meet the Federal Income Tax

The tax code has become near incomprehensible except to specialists.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Chairman, Senate Finance Committee, August 11, 1994

I would repeal the entire Internal Revenue Code and start over.

Shirley Peterson, Former Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, August 3, 1994

Tax laws are so complex that mechanical rules have caused some lawyers to lose sight of the fact that their stock-in-trade as lawyers should be sound judgment, not an ability to recall an obscure paragraph and manipulate its language to derive unintended tax benefits.

Margaret Milner Richardson, Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, August 10, 1994

It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is today, can guess what it will be tomorrow.

Alexander Hamilton or James Madison, The Federalist, no. 62

THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX is a complete mess. It's not efficient. It's not fair. It's not simple. It's not comprehensible. It fosters tax avoidance and cheating. It costs billions of dollars to administer. It costs taxpayers billions of dollars in time spent filling out tax forms and other forms of compliance. It costs the economy billions of dollars in lost output of goods and services from investments being made for tax rather than for economic purposes. It involves tens of thousands of lawyers and lobbyists getting tax benefits for their clients instead of performing productive work. It can't find ten serious economists to defend it. It is not worth saving.

How large are the costs of the federal income tax? They are larger than the federal budget deficit, larger than the Defense Department, larger than Social Security, perhaps as large as the combined budgets of the fifty states.

The tax system was better in 1986. Not perfect, but better. That year, President Ronald Reagan signed the landmark Tax Reform Act of 1986. It reduced the top marginal rate of taxation on personal income to 28 percent—down from an appalling 70 percent in 1980. It did away with more than $100 billion in wasteful tax shelters. It dramatically improved incentives to work, save, and invest. But it barely lasted four years.

What happened? Two presidents undid the 1986 act. First was George Bush. He stood side by side with the bipartisan congressional leadership as he signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. He proclaimed $500 billion in deficit reduction over five years, half in higher taxes, including a 31 percent tax rate on “the rich.” Second was Bill Clinton. In his 1992 campaign for the White House, he promised a middle-class tax cut. Once in office, he, too, became captivated with “deficit reduction.” On August 10, 1993, he signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, which passed the U.S. Congress by exactly one vote in the House of Representatives. It promised another $500 billion in deficit reduction, half in higher taxes, and included two higher tax rates on “the rich” to ensure that “those who benefited unfairly in the 1980s from the Reagan tax-rate reductions paid their ‘fair share’ in the 1990s.” In 1986, the income tax had just two rates: 15 and 28 percent. By 1995, it had five rates: 15.0, 28.0, 31.0, 36.0, and 39.6 percent.

The Declaration of Independence was in large measure a bill of particulars against British taxation. Its roots are found in the first Stamp Act Congress of 1766, when colonial leaders met to protest the British Stamp Tax. Other unpopular British taxes included a host of customs duties on paper, dyes, glass, and tea and a disguised tax on owners of property.

It's time for another Declaration of Independence, this time from an unfair, costly, complicated federal income tax. The alternative, as we argue in this book, is a low, simple flat tax.

WHAT'S AHEAD

The object of this book is to persuade you that a low, simple flat tax is the best possible replacement for the current federal income tax. Here's how we intend to proceed.

This chapter indicts the current federal income tax. In it we document the follow charges:

• The federal income tax is too complicated for ordinary taxpayers to understand.

• The federal income tax costs taxpayers more than a hundred billion dollars in compliance.

• The federal income tax costs the economy tens of billions of dollars in wasteful investments.

• The federal income tax is responsible for more than a hundred billion dollars in tax cheating.

• The federal income tax encourages lawyers and lobbyists to seek tax favors from Congress instead of earning an honest living.

Chapter 1 concludes with a brief history of the federal income tax.

Chapter 2 is all about “fairness.” We have learned, during the past fifteen years, that the most dangerous critique of the flat tax is the emotionally laden charge that it's not fair. We intend to dispose of this false, mistaken charge once and for all. Indeed, we claim that the flat tax is the fairest tax of all. To show that the flat tax is indeed fair requires a thorough discussion of tax terminology. We define such crucial terms as tax base, marginal tax rates, tax burden, consumption taxes, and equity, among others. In chapter 2 we also show that the flat tax is the only proposed replacement for the current income tax that has received support from opposite ends of the spectrum: in politics, from Jerry Brown and Dick Armey; in the media, from the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. Thus, on the issue of a well-designed tax system, our flat tax commands a broader array of support than any other proposal.

Chapter 3 spells out the mechanics and logic of the flat tax. We would replace hundreds of forms and thousands of regulations with two postcard-sized tax forms, one for business firms and the other for wage and salary earners. Our flat tax solves many tax problems that have challenged academics and politicians for years: it eliminates double taxation; it improves capital formation; it correctly defines the tax base; it provides true simplification; it dramatically improves incentives; it removes millions of low-income households from the tax net; it lowers the costs of compliance; it puts a serious dent in tax cheating; it even reduces the adversarial stance of the Internal Revenue Service toward taxpayers. Chapter 3 also deals with the transition, how we get from the current federal income tax to the flat tax, including such issues as the loss of deductions for home mortgage interest and charitable contributions and the replacement of complicated depreciation schedules with straightforward expensing, 100 percent immediate write-off, of all investment.

Chapter 4 addresses the big economic issues. Adopting the flat tax will, first and foremost, increase economic growth; in other words, the economy will increase its output of goods and services. It will increase investment by promoting capital formation. It will create new jobs and increase real wages by improving incentives to work. It will reduce interest rates immediately. It will reduce future budget deficits. It will make Americans more respectful of their government. It will even reduce crime because taxpayers will become more honest in filing their annual tax returns — a useful side effect of an intelligent approach to taxation.

Chapter 5 is a handy collection of questions and answers about the flat tax. During the past fifteen years we have presented our plan to more than a thousand audiences. We have heard, we believe, almost every single conceivable objection or concern that can possibly be raised about the flat tax. Here we assemble brief answers to the most frequently asked questions.

For specialists, we include an appendix with the language of our flat-tax law and a section on notes and references.

A NIGHTMARE OF COMPLEXITY

President Jimmy Carter called the income tax “a disgrace to the human race.” He was right. The best way we know to document Carter's charge is to take you on a tour of the Law School Library at Stanford University. It's a bit unnerving, as it reveals the nightmarish complexity of the income tax.

The Internal Revenue Code consumes enormous quantities of ink and paper. West Publishing Company, one of the official publishers of the federal tax code, published the 1994 code in two volumes. Volume 1 contains sections 1 to 1,000 (1,168 printed pages), and volume 2, sections 1,001 to 1,564 (210 pages). The table of contents displays 205 separate headings. West also prints a five-volume series entitled Federal Tax Regulations 1994, an essential companion to the tax code. Volumes 1—4, some 6,439 pages of fine print, apply to the income tax.

The Code and Regulations defy ready comprehension. A massive industry has grown up to service tax scholars, tax lawyers, tax planners, tax filers, tax accountants, and even tax collectors.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the agency charged with collecting federal income taxes, has its hands full. It has in service about 480 tax forms — the best known of which is Form 1040 — and has published another 280 forms to explain to you, the taxpayer, how to fill out the 480 forms. All told, it takes thousands of pages to explain the forms. Three publishing firms help out, each issuing three volumes of forms and explanations, each taking up almost a foot of shelf space.

Pausing in our tour, for the moment, we should note that the IRS sends about eight billion pages of forms and instructions a year to more than one hundred million taxpayers. Placed end to end, these pages would stretch 694,000 miles, or about twenty-eight times around the earth. The IRS despoils the environment, chopping down about 293,760 trees to print all of this paper. A postcard-sized tax form would go a long way toward saving America's forests.

The tour, in all, covers some 336 feet of shelf space. In addition to the laws and regulations, there are volume upon volume of tax court cases, journals for professors and practitioners, and books commenting on every conceivable aspect of federal income taxation. One benefit of our book is that it gives you a reasonably complete list of sources on federal income taxation (see the notes and references).

There are dozens of textbooks explaining the federal income tax along with an ever-increasing number of annual tax preparation guides. There are such specialized volumes as Bender's 1994 Dictionary of 1040 Deductions, which contains a nineteen-page double-column index to refer to items in the text. No wonder the ordinary citizen feels overwhelmed and threatened by the Internal Revenue Service. This is no way to run a tax system.

By the way, the price of a share of stock in H & R Block, the nation's leading tax preparation firm, increased by 20 percent in the first month following passage of the 1993 federal tax increase.

WHAT THE INCOME TAX COSTS THE AMERICAN PEOPLE

It's hard to imagine that any group of experts, however hard they tried, could design a worse tax system than the one produced by our Congress. The main beneficiaries of the income tax appear to be, first, the members of the two tax-writing committees, the Senate Finance Committee and the House Ways and Means Committee. Their chairmen lead their respective chambers in campaign contributions; other members of the two committees typically collect twice as much in contributions as their colleagues in the Senate and House. Second, members of Congress share the benefits of the federal income tax with more than seventy thousand highly paid lobbyists in Washington, D.C., and several hundred thousand lawyers, accountants, sellers of tax shelters, software suppliers, and others who earn a living on the tax system.

The federal income tax imposes two huge costs on the American people: direct compliance costs (record keeping, learning about tax requirements, preparing, copying, and sending forms, commercial tax preparation fees, audits and correspondence, penalties, errors in processing, litigation, tax court cases, enforcement and collection) and indirect economic losses from disincentives—economists call these “deadweight losses,” “excess burdens,” or “welfare costs” — due to the reduction in output incurred by the complicated, high-rate federal income tax (reduction in labor supply, reduction in capital formation, reduction in new corporate formations, reduction in new business formation, failure to expand existing businesses, investments designed to reduce taxes rather than produce income, commonly known as tax avoidance, and tax evasion, just plain cheating).

Studies of the burden of the tax system, what it costs the economy to administer the federal income tax, are relatively new. Studies of tax burdens, who pays what share of income taxes, are well established. This explains, in part, the obsession with issues of fairness and why every proposed change in federal income taxes is judged in terms of who wins and who loses.

In recent years, a growing spate of studies of the burden of the tax system, both in direct compliance costs and in indirect economic losses to the economy, reveals a disturbing result: The total costs are much higher than anyone has ever imagined. To give but one example, about fifty years ago, the Internal Revenue Service estimated the compliance burden of individuals at 1.2 percent of federal tax revenues; in 1969, the figure was raised to 2.4 percent of income tax revenues; in 1977, the Commission on Federal Paperwork raised the estimate to 3 percent; and in 1985, an IRS-commissioned study by Arthur D. Little concluded that the 5.4 billion hours of work expended in the taxpayers' paperwork burden for filing business and individual returns amounted to a staggering 24.4 percent of income tax revenues, the incredible sum of $159 billion. (These results, and the results of other academic and professional studies, are summarized in a 1993 book by James L. Payne, Costly Returns.)

The science of estimating compliance costs and indirect economic losses is, as noted, relatively new, and findings differ widely. Payne, for example, estimated the total costs of the federal tax system in 1985 at $363 billion, or 65 percent of actual collections. Others have reached higher costs in some categories of compliance and lower costs in others. In this chapter, we try our hand at estimating these costs, some directly and others by citing the best evidence available.

DIRECT COSTS OF COMPLIANCE

Let's take the most familiar items, federal income tax Forms 1040, 1040A, and 1040EZ. In 1994, the IRS reported preliminary statistics on 1992 returns. Altogether, taxpayers filed 113.8 million returns; of these, 65.7 million were the full Form 1040 (about 58 percent), 28.9 million Form 1040A (25 percent), and 19.1 million Form 1040EZ (17 percent). These percentages have been stable since 1990. Now turn to page 4 of the Internal Revenue Service 1993 1040 Forms and Instructions, “Privacy Act and Paperwork Reduction Act Notice.” It includes a section titled The Time It Takes to Prepare Your Return. Here's what it says.

We [the IRS] try to create forms and instructions that are accurate and can be easily understood. Often this is difficult to do because some of the tax laws enacted by Congress are very complex. For some people with income mostly from wages, filling in the forms is easy. For others who have businesses, pensions, stocks, rental income, or other investments, it is more difficult.

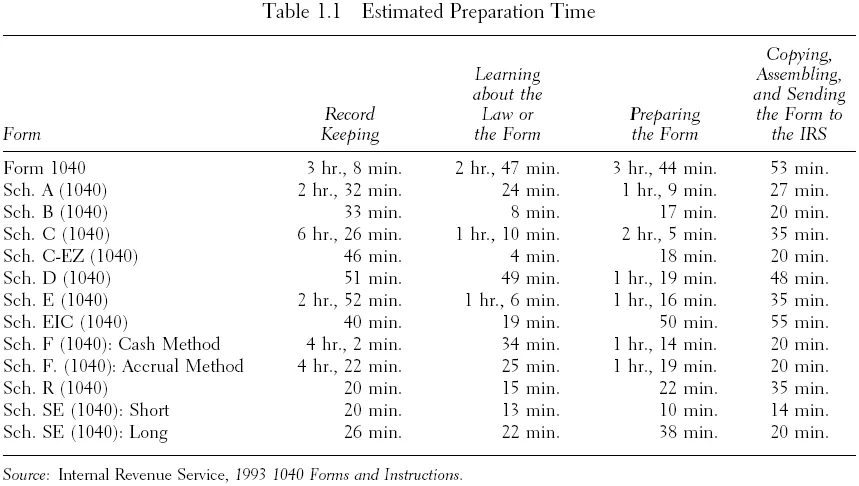

Page 4 includes a table titled Estimated Preparation Time, which is the average time required of taxpayers. We have reproduced it as table 1.1.

The table, of course, is incomplete. It omits numerous forms. The standard 1040 booklet includes, in addition to those in the table, Form 4562, Depreciation and Amortization, which includes eight pages of instructions in the 1040 booklet, and Form 8829, Expenses for Business Use of Your Home. The IRS estimates that it takes more than forty-six hours to complete Form 4562 and about two and a half hours for Form 8829. (Perhaps to avoid frightening taxpayers even more, the Form 1040 booklet does not include such commonly used forms as 2106, 2119, 2210, 2441, 3903, 4868, 5329, 8283, 8582, 8606, 8822, and 8829. If you don't need these forms, better you should remain ignorant of them.) A full accounting would require detailed knowledge of every tax form, how many of each schedule were attached, and how much estimated time each schedule requires. Nor have we yet mentioned business taxpayers, who must cope with a much heavier reporting burden.

To the arithmetic. The IRS estimates that the average total time to complete and file Form 1040A is six hours, thirty-three minutes. The time expands appreciably when it is necessary to attach any of Schedules 1 (Interest and Dividend Income), 2 (Child and Dependent Care Expenses), and 3 (Credit for the Elderly or Disabled) or any of the forms for EIC (earned income credit), IRA (individual retirement account) distributions, pension income, or Social Security benefits, so a reasonable average time is probably about eight hours. The time for Form 1040EZ is one hour, fifty-two minutes.

Few people treat filing tax returns as leisure activity; most people we know would rather fish, ski, or watch television. So we need to make some assumptions about the value of the time individuals expend complying with taxes.

For those who file Forms 1040EZ and 1040A, we use a conservative figure — the federal minimum wage of $4.35 an hour. For those who file Form 1040, we use the average hourly earnings in private, nonagricultural industry of about $10.80. These numbers are well below IRS costs of $21 an hour to process tax-related information back in 1985, which would be much higher today, or Arthur Andersen's employee cost of $35 an hour, again from 1985.

For those who file Form 1040EZ: 19.1 million taxpayers times one hour, fifty-two minutes, times $4.35 an hour totals $155 million. For filers of Form 1040A: 28.9 million taxpayers times eight hours times $4.35 an hour totals exactly $1 billion.

For filers of Form 1040, the calculations require a rough estimate of the average time per return. To be conservative, we will add up the times shown in IRS Form 1040 (minus any double counting) and add an additional 50 percent to include forms not listed (the depreciation form alone amounts to another forty-six hours). Our arithmetic sums to about 45.0 hours, which we adjust up to 67.5 hours for unlisted forms. Adding up: 65.7 million taxpayers times 67.5 hours times $10.80 an hour equals almost $48 billion. Altogether, compliance costs for individuals in 1993, at reasonable estimates, amounted to about $50 billion. Arthur Little's 1985 estimate was $51 billion, derived from 1.8 billion hours of work at an average cost of $28 an hour. (In 1985, eleven million fewer returns were filed compared with 1992. Also, the 1990 and 1993 tax increases significantly increased reporting requirements.) Our number, therefore, is extremely conservative.

The Arthur D. Little study concluded that twice as many hours were spent complying with business tax returns. It used a figure of $28.31 as the h...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- The Flat Tax's Silver Anniversary

- Preface

- 1. Meet the Federal Income Tax

- 2. What's Fair about Taxes?

- 3. The Postcard Tax Return

- 4. The Flat Tax and the Economy

- 5. Questions and Answers about the Flat Tax

- Notes and References

- Appendix: A Flat-Tax Law

- About the Authors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Flat Tax by Robert E. Hall,Alvin Rabushka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.