What is technology? We use this word in multiple ways. On one hand, technology refers to tools that humans create so they can achieve some sort of goal. A hammer, for instance, is technology. Eyeglasses, technology.1 On the other hand, when we use the word technology today, we most often refer to digital technology. If your friend says that she’s really into technology, she means digital gadgets, not garden tools. And as microchips become smaller and smaller and cheaper and cheaper, more “old” tools are becoming, to some degree, digital. You can get an app to control your lights, your sprinklers, and your robot vacuum. This “internet of things” is made up of networked thermostats and other devices that can now be controlled by smartphones—or your voice. We use the word technology in both ways, but we also must realize this shift in terminology that prioritizes digital technologies as simply “technology.” As I mentioned in the introduction, all of these tools are technology, but digital technologies invite an immersion that affects our formation in a more persistent way than hammers, for instance. But how do these technologies form us? Are they tempting us with a particular vision of human flourishing?

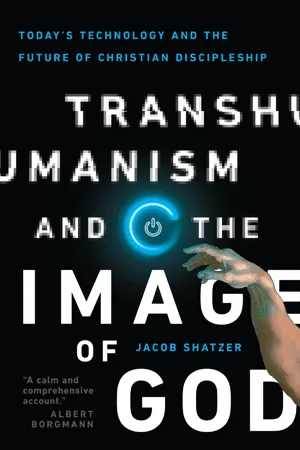

I’ll repeat my description of transhumanism from the introduction. Transhumanism and posthumanism are two related philosophical movements tied closely to the promises of technology. Posthumanism argues that there is a next stage in human evolution. In this stage, humans will become posthuman because of our interaction with and connection to technology. Transhumanism, on the other hand, promotes values that contribute to this change. Transhumanism aims at posthumanism, and both are based to a large degree on the potential offered by technology. In a way, transhumanism provides the thinking and method for moving toward posthumanism. Transhumanism is the process, posthumanism the goal. They share a common value system, and in this book I will primarily refer to transhumanism but also to posthumanism.

Technology promises seemingly limitless possibilities, and transhumanism and posthumanism trumpet this potential. Some of the possibilities sound far-fetched, and many people hesitate to adopt them. Few today would volunteer for the opportunity to upload their consciousness into a computer, for instance. Whether they recognize something less than human about this type of “consciousness” or simply react emotionally against it, their hesitancy remains.

But can this stance last? While some people will change their minds based on careful research and thought—including theologians of various religious perspectives—others will gradually change in less dramatic senses because the way we use tools today changes us for tomorrow.2 Our use of the tools that humans make in turn shapes us as humans; these tools can make us into something else through our interaction with them. This change is because tools come with a governing logic, and that logic projects a certain type of future.3 Some technologists even speak as though technology itself “wants” something that it is pursuing.4 Created things come with projects instilled in them by their creator, so tools we make carry these projects with them.5 And these projects, this governing logic, shape us. This idea disturbs us, as Harari puts well: “We like the idea of shaping stone knives, but we don’t like the idea of being stone knives ourselves.”6 Our tools draw us toward one thing and away from another; “Just as every technology is an invitation to enhance some part of our lives, it’s also, necessarily, an invitation to be drawn away from something else.”7 We make them; they make us.

Considering this issue more deeply, we can turn to some helpful definitions and distinctions. First, we are circling the discipline of media ecology, “which studies how technology operates within cultures and how it changes them over time.”8 We will be concerned with the impact of technology on Christian culture, especially how Christians consider what it means to be human and how to live a flourishing human life. Second, we must recognize that this happens on many levels. Theologian Craig Gay draws on Jacques Ellul to speak about waves, currents, and depths: just as the ocean has surface waves, currents beneath those, and depths below all of that, our treatment of technology and moral formation must take into account these various levels and their connections.9 Another theologian identifies four “layers” of technology: technology as hardware, as manufacturing, as methodology, and as social usage.10 While some might still insist that our technology questions are only about balance, not good or bad, we must reckon not only with good and evil in the present but with good and evil in regards to who we are becoming.11

Another writer refers to the difference between technology and technological people. As he puts it,

There is nothing wrong with technology per se. But there is something wrong with technological people. The difference between the two is that “technology” is merely a tool used to pursue substantial human ends, whereas technological people abandon human ends in favor of exclusively technological ones. The former view is classical, the latter that of Silicon Valley dataists and transhumanists for whom human beings are themselves merely “obsolete algorithms” soon to be replaced by synthetic ones far superior to them in every way.12

The difficulty of employing technology without being shaped into “technological people” is clear.

Bioethicist Erik Parens refers to this phenomenon—the way we shape our tools and they shape us—with the term binocularity. Focusing on human enhancement, Parens notes that we can view ourselves as self-shaping subjects (the creativity stance) or as objects, thankful recipients of someone else’s shaping (the gratitude stance). We shouldn’t choose between these two but rather oscillate between them, developing a binocularity that gives us a fuller vision of—in Parens’s case—issues of bioethical enhancement.13 Now, we have to acknowledge that it is difficult to look through both of these lenses at once. But this binocularity can help us remember that we cannot view technology only as something that we use as active subjects; it also works on us and shapes us. Our current engagement with technology is not a neutral practice but one that continues to shape us to think about—and to love—technology in certain ways.

We’re not talking about the way technologies themselves can become idols, but how our use of technology can change us in deep ways, making us think and feel in ways that we may not expect.14 Any adequate response to technology must ask more than, “Should we use this technology right now?” Even as we acknowledge that our (and our parents’ and grandparents’, friends’ and neighbors’) engagement with previous technology shapes our current use of technology, we must look carefully at our current practices and how they might shape our, our children’s, and our grandchildren’s engagement with technology in the future. For example, how do our personal technologies change our ability to pay attention? Alan Jacobs refers to our “interruption technologies” to highlight the problem this poses.15 And, as we’ll consider below, attention is more than simple focus. These considerations matter. Our current use of technology forms us morally. What sorts of practices today can help us retain the best of what it means to be human in the future? We should not think about technology use today without considering who we will turn into tomorrow as a result.

But isn’t this simply the approach we have always had to take toward our tools? Why the alarm and the connections to transhumanism? In order to see how our choices about digital technology relate to other sorts of tools, we need to take a brief detour into the fields of neurology and cyberpsychology.

Changing Our Minds

A burgeoning field of scholars document and describe the impact of digital technology on humans. In particular, our use of technology seems to be changing our brains and thereby our behavior.16 The most visible—and memorable—early treatment of this issue was Nicholas Carr’s aptly titled “Is Google Making Us Stupid?,” published by the Atlantic in 2008.17 Carr followed this with a book-length treatment in The Shallows.18 Others have drawn similar conclusions. At the most basic level, studies are beginning to show that our technology use is changing us on a neurological level: our brains are changing.19

Cyberpsychologist Mary Aiken has analyzed these changes not only on the level of the ability to think but also on specific behaviors. This varies from person to person, depending on their tendencies and temptations. As Aiken explains, “Whenever technology comes in contact with an underlying predisposition, or tendency for a certain behavior, it can result in behavioral amplification or escalation.”20 Later she elaborates, “The cyberpsychological reality: One can easily stumble upon a behavior online and immerse oneself in new worlds and new communities, and become cyber-socialized to accept activities that would have been unacceptable just a decade ago. The previously unimaginable is now at your fingertips—just waiting to be searched.”21 In other words, our use of digital technology not only changes our ability to concentrate and focus—one of Carr’s main points. It also introduces us to and socializes us toward behaviors that we may not have encountered otherwise.

Taking the issue even broader, neuroscientist Susan Greenfield has written her appropriately titled book Mind Change: How Digital Technologies Are Leaving Their Mark on Our Brains. She named the book Mind Change because she sees parallels between what she’s observing and climate change: “Both are global, controversial, unprecedented, and multifaceted.”22 Our brains are changing, because the brain “will adapt to whatever environment in which it is placed. The cyberworld of the twenty-first century is offering a new type of environment. Therefore, the brain could be changing in parallel, in correspondingly new ways.” Furthermore, “To the extent that we can begin to understand and anticipate these changes, positive or negative, we will be better able to navigate this new world.”23 She identifies three main realms: social networking (identity and relationships), gaming (attention, addiction, and aggression), and search engines (learning and memory).24 Each of these areas leads not only to changes in behavior, as Aiken points out, but also to real neurological changes in the brain.

Though studies are beginning to make these issues clear, some might still wonder whether this is all an overreaction to a new technology. Before we discuss why I think the game has changed, we have to realize that part of the issue is that the sorts of changes scholars are beginning to notice will take years and years to understand better. As Aiken puts it, especially in reference to technology’s impact on children, “If you find yourself questioning the dangers of early digital activity and insist on hard evidence backed by science, then you’ll have to wait for another ten or twenty years, when comprehensive studies—the kind that track an individual’s development over time—are completed.”25 But if these technologies have the formative power that they seem to, we do not have the luxury to simply wait and wonder. Forming is happening now. But isn’t this always the case: that our tools are forming us?

Why the Game Has Changed

The short answer is yes. But I still think that we’re dealing with a very different game when we’re talking about digital technology. I have three primary reasons. First, the type of access that we have to digital technology is different from previous tools. Second, studies on addiction demonstrate that digital technology is a game changer. And third, I’m convinced that technology does an excellent job of recruiting disciples into its way of viewing the world. Or, as we discussed above, technology makes “technological people” very effectively. Let’s deal with each of these in turn and flesh them out.

First, digital technology is different from previous technology because of the speed of access and the immersion many experience in the technology. As one scholar explains, “The instant, uninterrupted, and unlimited accessibility of both activity and content that i-tech provides is significantly changing the big picture, not only isolated frames.”26 The sheer amount of time that we spend with screens makes this different from other issues of technology.27 Not only is the amount of time different, but the volume of content that people take in is a new issue as well.28

The ease of access to digital technology enflames existing problems. For instance, bullying is a constant issue with children as they grow up and learn to negotiate social spaces. But trends in recent years have been alarming, as more and more cases lead...