- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

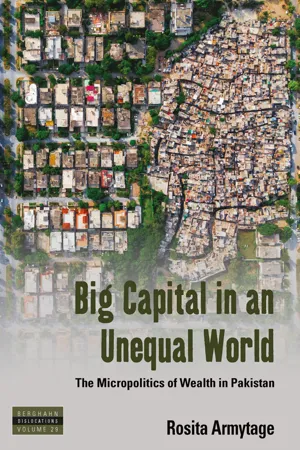

Inside the hidden lives of the global "1%", this book examines the networks, social practices, marriages, and machinations of Pakistan's elite.

Benefitting from rare access and keen analytical insight, Rosita Armytage's rich study reveals the daily, even mundane, ways in which elites contribute to and shape the inequality that characterizes the modern world. Operating in a rapidly developing economic environment, the experience of Pakistan's wealthiest and most powerful members contradicts widely held assumptions that economic growth is leading to increasingly impersonalized and globally standardized economic and political structures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Big Capital in an Unequal World by Rosita Armytage in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

– Chapter 1 –

MIDDLE-CLASS WOMAN IN AN ELITE MAN’S WORLD

A few nights into my fieldwork, I sat in the smoke-filled home of Abid and Kaleem Afridi in a wealthy Lahori neighbourhood. Together with their friend Shahid, we sat and brainstormed a list of high-profile businessmen I should seek to interview. Abid and Kaleem, in their early and late thirties respectively, were businessmen from an economically and politically powerful family in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). The brothers divided their time between their family home in KP, and their homes in Islamabad and Lahore. Their friend Shahid, was the owner of a large manufacturing firm and the son of a prominent Punjabi political leader.

As the three men chain-smoked and scrolled through the address books on their mobile phones, identifying the friends and acquaintances they could call on to meet with me, I furiously scribbled first one, then two, then five pages of names. Between the three men, together with the social contacts of those they knew well, was an enormous repository of personal social contacts at the highest level of Pakistani business and politics.1 This list reflected the three men’s shared understanding of the wealthiest and most successful businessmen in Lahore, and became the first version of my ever-expanding list of businessmen to meet for my research.

I spent a great deal of time in the large second home of Abid and Kaleem in Lahore during my fieldwork. During this time the two brothers travelled between their primary residence in Islamabad (where their wives and children lived), their village and extended family home in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the eight-bedroom Lahore home, often departing for various meetings or family obligations and leaving me to coordinate my meetings and write-up my fieldnotes in one of the armchairs in their home office with Jamil, the cook/housekeeper, a driver and an armed security guard. At various intervals, one or both of brothers would arrive back in Lahore where I was living without warning and demand we go for coffee or lunch, or sit and chat in their home office as they fielded phone calls, chain-smoked and intermittently yelled out to Jamil for omelettes, paratha and endless rounds of chai. The two brothers and their younger cousin Shahzar became three of my closest informants and most valuable cultural guides, as well as close friends. Each took it on themselves to seriously consider each of my questions, even when they clearly found my interests odd, or the answers patently obvious.

Between October 2013 and January 2015, I conducted fourteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in Lahore, Islamabad and Karachi. Though I engaged in interviews with over ninety of the country’s most powerful, influential and wealthy business people and politicians, their families and friends and the government regulators tasked with monitoring their behaviour in business, the vast majority of my time was spent conducting participant-observation – hanging out with and observing the many elites who became both my informants and my friends. Most days I spent large amounts of time meeting someone for lunch; sitting and chatting in living rooms, offices, or cafes; sharing my informants’ chauffeured commutes to their factory sites; visiting factories and talking with the owners and managers and professionals who ran them; attending long drawn out nights of drinks and conversation with various groups of friends and associates in their homes or private clubs; and intermittently attending large parties or weddings. The vast majority of my informants were male, ranging from 24 to 87 years old.

As with most fieldwork, my access to informants centred on the relationships I developed with a few key gate-keepers to the social worlds of elite Lahore, Islamabad and Karachi. The close friends and informants I made in these cities opened the door to my interviews in each location, and they and a number of those I interviewed, in turn invited me to their offices, factories and homes, and to cafes, dinners, birthdays and weddings. It was at these social gatherings where much of my best participant-observation was undertaken.

Given my interest in understanding how economic power is acquired and protected, and the estimates of my new friends on the revenue streams of their peers and associates, I settled on a baseline for inclusion in my study, with the requirement that the business families included in this research generate a minimum of US$ 100 million in revenue per year (with the inclusion of a few families who had lost this level of wealth, or were near to achieving it).2 Above this baseline, my informants estimated that around 100–200 families – a specific sub-class within the elite – dominate the nation’s highest revenue and most profitable businesses. All 92 of the businessmen I interviewed came from families on this list, as did many of the others I socialised with informally.3

As my research progressed, it became clear that in addition to owning and managing major business interests, many of my informants were also current or former politicians. Others, like Abid and Kaleem’s friend, Shahid, had a close family member in politics, no more distantly related than a brother, first-cousin, or uncle.4 Many of the businessmen I came to know funded, or were otherwise engaged in, the backstage processes required to support local and national election campaigns, or the deal-making strategies of their close relatives in politics. Consequently, seeking to understand the relationship between big business and privilege, I also interviewed a number of politicians and senior bureaucrats, and received insights into the relationship between big business, politics, the formal structures of the state, and power and privilege. It became clear that the economic and political processes of the nation, and the individuals who directed them, were so deeply intertwined through social and kinship ties that it was impossible to delineate business at this scale from formal politics or the operation of government.

My secondary group of informants were the government regulators and lawyers tasked with representing and prosecuting allegations of corruption among elite business. Accessing these people was made easier once, after six months in Lahore, I moved to Islamabad where most were based. The people I interviewed in this category were staff or former staff of the National Accountability Bureau (NAB), the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), the Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP), the Capital Development Authority (CDA), the Department of Industry and Production, senior counsel of the Supreme Court and a number of private lawyers representing the interests of high-profile cases against business empires. Most of these individuals were upper-middle class and firmly outside the elite social circles attended by the business and political elite. Consequently, though I socialised with a number of lawyers at elite gatherings, my meetings with regulators and other civil servants were confined to semi-structured interviews in their places of work, casual discussions in the car rides to and from their offices to the court house and observation of their interactions at the courts.

The help of the Afridis was invaluable in establishing me in Lahore, and in starting the round of introductions which snowballed to allow me to meet a large cross section of the nation’s urban elite. Alongside the ease and generosity with which my new friends sought to help me, however, lay a whole suite of assessments about me, and my position and status, that informed their willingness to assist and spend time with me. These assessments had a profound impact on my ability to access their lives and those of their peers, and resulted in relationships considerably different from those anthropologists usually experience when researching poor or marginalised subjects. The inversion of this traditional power dynamic in the research relationship, and the background of political instability in which my research occurred, shaped every aspect of my fieldwork in Pakistan.

Ethnographically Researching Elites

Elites are often intensely private groups that are difficult for researchers to access (Gilding 2010; Jabukowska 2013; Pina-Cabral and de Lima 2000, Shore 2002; Smith 2013). The challenges of access are even more pronounced in traditionally closed societies (Abbink and Salverda 2013), and in contexts riven by distrust and political instability (see Green 1994; Robben and Nordstrom 1995).

Within sociology, geography and political science, disciplines with a long history of relying upon elite informants, it has widely been noted that the construction of power dynamics between the researcher and the researched is rooted in social identities of gender, ethnicity and class, and the dynamics between them. The literature on researching elites within these disciplines focuses largely on the heavily structured world of formal interviewing.5 Though there is also a significant body of research on elites from within sociology, political science and historical studies,6 and more recently, the emergence of a popular genre critiquing Western elites,7 elites across the world remain understudied using anthropological and ethnographic methods which attempt to understand these groups from within (Abbink and Salverda 2013).

The long-term nature of ethnographic fieldwork differs from these accounts in that it provides critical insights into the reproduction of elite power, which are unavailable through other research methods, as it substantially erodes the ability of informants to present a façade of their life: discrepancies between what is said and what is observed emerge as intimacies are shared, and the lives of the researcher and the researched intermingle. However, a particular set of methodological challenges remain for anthropologists working with elites.

Relying on ethnography and participant-observation, anthropologists spend a great deal of time and analytical effort in assessing and understanding the behaviours, attitudes and beliefs of their informants, and in interpreting what they reveal about their societies. Beyond noting that it is critical to develop rapport with our informants, however, we spend much less time examining the ways that our informants evaluate and determine the role we will play in their own lives, and how their assessments determine the aspects of their lives to which they permit us access. The issue is particularly salient for powerful and elite informants whose influence, networks and education make them particularly effective in crafting their self-representations; how they are represented to members of their own and other classes; and in modulating how they portray themselves to a researcher or observer.

Osburg noted that anthropology’s assumptions about ‘studying up’ often leave anthropologists ill-equipped to handle many of the situations they encounter. He noted that:

Building rapport is usually portrayed as the anthropologist winning the trust of the reluctant locals and as something the anthropologist does, rather than something that is done to him or her. (Osburg 2013: 299)

His observation echoed much of my own experience of researching powerful men. It was often they who decided the tone and nature of our relationship. I could encourage or set limits on the terms of this relationship, but rapport could only be built with willing subjects who had made a conscious calculation on whether to entertain the relationship, and whether or not it was worthwhile for them to do so.

Halfway through my fieldwork, by which time he had shared many of the intimate details of his life, including much that was illegal, I asked my close informant Abid why he felt he could be so open with me. Abid answered using the Urdu nickname he had early on translated from my own English nickname:

Gulabo [Rosy], first, I am an excellent judge of character. I know the sort of person you are. Second, you cannot hurt me. If you ever used my name and details, I would deny everything and tell everyone you made it up. I have a big family and many friends here, and you are just by yourself … I also had my friends in the intelligence agencies run a background check on you.

Beyond his own sense of impunity, Abid’s answer revealed the interlinking power dynamics which determined my ability to access the lives of some of the nation’s most powerful businessmen and politicians. It also revealed the ways in which a number of my informants assessed and evaluated my position within the worlds they dominated. In a few sentences, Abid affirmed his confidence in his own judgment; the extensive networks of elite businessmen, politicians and senior government of which he was a part; and his clear-sighted assessment of my role and vulnerable position within his society. Abid made it clear: as a foreign, unmarried female, I had very little power within his world, and my research was possible because he, and others in his extended network, permitted it. Like most of my informants, he was aware of his power and influence – and of my relative lack of it. My informants had assigned me my ‘proper place in the social order’ (Warren and Hackney 2011: 9), though as this chapter explores, my proper place sometimes shifted.

Gaining and Restricting Access

The businessmen, and occasionally women, I interviewed often invited me to their homes, where we had long and disparate conversations on stiff velvet upholstered couches while snacking on samosas and sandwiches, drinking tea in china cups brought in by staff on silver trays. At other times, introductions from existing contacts led to formal meetings in nondescript fluorescent-lit offices. A number invited me to meet them for interviews over lunch at their private clubs, or over dinner with their friends and associates. Others I met invited me to tour their factories, enabling me to witness an array of production standards, technology and worker conditions. Some of these factories reflected the highest standards of modern production and technology. At these sites factory owners proudly explained the innovations in their imported Japanese or German machinery, the types of items that could and should be bought more cheaply from China, and the importance of hiring local workers to minimise the likelihood of interference by local extremist groups. In other locations around Lahore and in KP, thin barefoot workers grimaced, faces streaked with dirt and grease as they worked on ancient looking machinery, the hems of their shalwar kameez trailing dangerously close to swirling machinery and open flames. In Karachi, I visited factories in the Korangi Industrial Area accompanied by a vehicle of four private armed guards at the insistence of a Karachi-based businessman, the guard vehicle in almost comic contrast to the white Honda in which I followed with the driver of a middle-class friend. Also in Karachi, were the visits to gleaming high rise office buildings where the owners of investment companies casually made stock trades during the intermittent pauses in our conversation.

I had originally intended to focus on only the active heads of each business empire – the patriarchs – but this was initially difficult.8 Instead, my emerging friendship with Shahzar, the cheeky, UK-educated, 24-year-old cousin of Abid and Kaleem, opened doors to the younger, third generation of businessmen in Lahore, and his ‘batchmates’ from Pakistan’s most prestigious private boys’ school, Aitchison College (discussed in more detail in Chapter Three). These introductions provided a very different view of the structure and functioning of family business, and valuable insights into the lifestyles of the younger generation of elite men. This younger group were often quite willing to discuss their difficulties proving themselves in business, as well as their experiences with dating, rishtas (marriage proposals) and the process of identifying a suitable spouse. Many of these men also spoke openly about their relationships with their fathers and mothers, and the contrast between their lives as students in North America or the UK, and their lives in Pakistan.

Yet it was Shahzar’s socialite girlfriend, Maryam, a member of the old Established Elite, who provided access to most of the social events I attended in the first months of my fieldwork. Maryam brought me along to the gatherings she hosted in the self-contained suite within her family home, invited me to the weddings of her friends, and on a number of occasions, brought me to the homes of her friends’ grandparents, genteel and welcoming people whose families had taken over manufacturing industries abandoned by the British after independence. These social events provided a much-needed chance for participant-observation and a relief from the social firewall that seemed to have blocked my hopes of establishing social interactions with the older business owners I interviewed during the day.

Five months into my fieldwork, during a short trip to Islamabad, an old acquaintance invited me to accompany him to the home of a friend he thought may be able to help with my research. His friend, Kamil, was a charming man in his fifties from one of the most respected old families of Karachi, a political insider and a self-proclaimed ‘wheeler and dealer’. Kamil invited me to the dinner party he was hosting later that week, and not wanting to miss the opportunity, I extended my stay in Islamabad. Over the course of the dinner party, I was invited to two more events, and met half a dozen of the country’s leading businessmen, politicians, senior bureaucrats and media owners. Recognising the advantage of being situated nearer to this group, and the social capital I had instantaneously acquired as a guest of Kamil’s, I decided to relocate to Islamabad for the second half of my fieldwork. My network grew exponentially. On several return trips to visit business families and social clubs in Lahore and Karachi, I found that the doors to the patriarchs of the family empires that had remained so steadfastly closed to me during the first five months of my research, miraculously opened with the introductions of my new friends.

As I came to know many of these businessmen better, I visited their homes and attended their parties, dinners, private clubs and weddings, socialised with their families, friends and colleagues, had countless meals, cups of chai, and glasses of whisky, and had many share their stories as they became my friends and highly valued advisors. Some of my best fieldwork was conducted after midnight, when the mood was at its most relaxed and open, and the men and women at these gatherings spoke more openly and self-reflectively than they would ordinarily do in the interviews held in their offices in the exposing glare of day. My fieldwork now shifted between the formal interviews I conducted during the day, and the social events I attended most evenings. On most days, I would conduct an interview, then meet one of my close informants for long drawn out cups of coffee at a local cafe or in one of their homes, and then attend a social event, dinner or party in the evening.

The Geopolitics of Fear and Distrust

The period in which I conducted this research was a particularly turbulent time in Pakistan, characterised by a number of major terrorist attacks, military blocks and operations, large-scale jalsas (demonstrations) and government shut-downs. My research was also informed by the security challenges that differentiate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Note On Anonymity

- Introduction. Making Money in an Unequal and Unstable World

- Chapter 1. Middle-Class Woman in an Elite Man’s World

- Chapter 2. Creating and Protecting an Elite Class

- Chapter 3. Old Money, New Money

- Chapter 4. Making an Elite Family

- Chapter 5. The Elite Network

- Chapter 6. The Culture of Exemptions

- Conclusion. What Pakistan’s Elite Reveals about Global Capitalism

- References

- Index