![]()

William Eggleston Symposium

Morning Panel

Moderator: Lisa Howorth

Panelists: Megan Abbott, Maude Schuyler Clay, and William Ferris

Robert Saarnio: This symposium was financially underwritten by both Friends of the Museum and the University of Mississippi Lecture Series and would not have happened without that support. The exhibition itself entailed a thirty-month collaboration among Museum staff, including collections manager Marti Funke, and two essential partners, guest curator Megan Abbott and consulting advisor Maude Schuyler Clay. Suffice it to say that without Megan’s brilliant curating, Maude’s invaluable contributions, and Marti’s coordinating efforts, this exhibition would not have been accomplished at the distinguished level that you see in our galleries.

We must also express profound gratitude to William Ferris, whose gifts of these Eggleston prints to the Museum’s permanent collection made everything ultimately possible. Bill traveled from Chapel Hill to be with us today, serving as both panelist and moderator. We are indebted to this remarkable scholar, friend, and supporter. Please join me in extending the very warm round of applause to our great friend. Our panelist speakers today have traveled from the Delta, New Orleans, New York, Memphis, Chapel Hill, and across campus; and we are deeply grateful to each of them.

They will be introduced by their panel moderators, but we want to express unequivocally how proud and honored the entire Museum community is to be joined today by Bill Ferris, Megan Abbott, Maude Schuyler Clay, Lisa Howorth, Emily Neff, Richard McCabe, and Kris Belden-Adams. Thank you all so very much for the privilege of your participation and your expertise. It is now my distinct pleasure to introduce the moderator of our first panel this morning, author, art historian, and friend to everyone in this room, Lisa Howorth.

A native of Washington, DC, Lisa has lived in Oxford since 1972. She and her husband, Richard Howorth, founded Square Books in 1979 and later opened an annex store, Off Square Books, and Square Books Junior, a children’s store. After earning an MS in library science and an MA in art history, Lisa was a reference librarian and an associate professor of art and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. She has edited four books, contributed to magazines and other publications, written the novel Flying Shoes, and is at work on a new novel. Please join me in thanking and welcoming Lisa Howorth.

Lisa Howorth: Thank you. Thanks to everybody involved. It’s my pleasure to be part of this symposium, and I’m grateful to be invited. Let me go ahead and introduce the panel.

Miss Megan Abbott is the award-winning author of nine novels as well as a nonfiction book, The Street Was Mine: White Masculinity in Hardboiled Fiction and Film Noir. She’s also the editor of A Hell of a Woman, an anthology of female crime fiction, and has written for the New York Times, Salon, and other publications. After receiving a PhD in literature from New York University, she taught at NYU, the State University of New York, the New School, and the University of Mississippi, where she was Grisham Writer in Residence in 2013–2014. Much of her writing is inspired by William Eggleston’s photography. We miss her, and we’re glad to get her back here any way we can. I also want to add this, just in: she’s a 2016 Edgar Award Nominee for Best Short Story with “Little Men.” That’s another feather in her cap, and we’re so glad she’s here.

Miss Maude Schuyler Clay was born in Greenwood, Mississippi, where her family has lived for five generations. That’s saying something, isn’t it? After attending the University of Mississippi and the Memphis Academy of Arts, she was an intern for her cousin, photographer William Eggleston. She then moved to New York City, where she worked at Light Gallery and was the photography editor and photographer for Esquire, Fortune, Vanity Fair, and other publications. After returning to the Mississippi Delta in the late 1980s, she continued her color portrait work and began a series of black-and-white photographs. The University Press of Mississippi published her monographs Delta Land and Delta Dogs, and Steidl published her book of color portraits Mississippi History with a foreword by Richard Ford. She’s received five awards for her photography from the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters and was the 2015 recipient of the Governor’s Award for Excellence in Visual Art. And, another tidbit of breaking news, her show at the Ogden Museum in New Orleans just opened to packed SRO crowds. We’re very excited and proud of Maude for that.

Okay then, the big dog, William Ferris, is Joel R. Williams Eminent Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and adjunct professor in the Curriculum in Folklore. He is senior associate director at the Center for Study of the American South and a former chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Prior to his role at NEH, Ferris served as director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi, where he was a faculty member for eighteen years. Wow. Amazing. Time flies when you’re having a good time, right? We did. Ferris has written or edited ten books, created fifteen documentary films, and coedited the award-winning Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. His last three books provide an extraordinary trilogy of his documentation of life in the South through nearly six decades of photographs and interviews. I also want to add that Billy’s entire family is one of artists, art supporters, educators, and writers. They’re kind of a Mississippi treasure trove, and what the hell Bill’s doing up there with all those Yankees, I do not know. It’s a travesty, right? I hope someday to be asked to be on a panel about Bill Ferris, because I know some stuff. It would be a good panel. I guess that’s all I have to say.

Megan Abbott: Before we start talking, Robert and Marti asked me to tell about my role in this rather miraculous exhibition. We first started talking about it in 2013; and I want to thank Robert, Marti, and the Museum for this incredible opportunity to play a small part in the exhibition that was a major undertaking for them. I thank Robert for engaging and shepherding me and Marti for all the stunning work she did in putting the exhibition together. For those of you who saw it last night or have seen it before, it feels like a whole new experience being in those rooms.

This morning we will talk about William Eggleston with those who know him and have stories and insight. I come as an outsider. His work has meant so much to me; and, like countless others, I was drawn to his photographs long before I even knew his name. I only know how the pictures made me feel, the kind of uncanny spell they put me under—first as a teenager and later as an aspiring writer yearning for transport. Looking for a cheat.

I think I thought, and I still think this: “Maybe if I look at that photo long enough, the back of the woman’s head, her finely tended coiffure, a story will surface for me. I will know what I want to tell.” Somehow for me, as for countless other writers, and filmmakers, and artists, it did work. It absolutely did. The photograph was there, and the spell was enchanted.

I’m fairly sure the first Eggleston I saw was the first color photo he ever made: the famous one of the grocery store clerk, his hair oddly lustrous, his mouth slightly open, pushing a hard, glittery tangle of shopping carts into the store. His palms are pressed just so. At the time, I didn’t know about Eggleston’s place in the history of photography, the breakthrough of color photography, the way he’s been positioned often rather narrowly as a “Southern” photographer, a “regional” one, a photographer of the weird. All I knew was, when I looked at that photo, I saw a world I knew, part of the world I lived in: Kroger’s and fluorescent lights and bright shiny wrappers, and the hard and soft faces of strangers and intimates. And part of the world that I experienced from the inside out: fevered, heavy, mysterious, loaded, beautiful. All the things I think we feel when we look at one of his photos.

Then it’s no surprise that Eggleston is and always has been a catnip for writers, artists, storytellers of all kinds, from David Lynch, which is how I first discovered him, through Gus Van Sant to Sofia Coppola, and Harmony Korine. I suppose it’s a cliché to say that when you look at Eggleston’s photos, they seem to tell a story. I don’t think that’s true. They’re not narrative images like we might see in, say, Robert Capa or Dorothea Lange. Eggleston’s photos don’t connect dots for us. They don’t assert or announce. They don’t tell at all. But maybe it’s more precise to say that when you look at them, you make the story.

Stories, after all, have a beginning, a middle, and an end. We can see all three parts in a photo in an instant in some photos: a young boy of privilege, left alone, a toy grenade in his hand, to reference the famous Diane Arbus photo. It’s all right there in the picture. With Eggleston, it’s different. The photographs don’t offer three acts, or even a first act. Instead, the photographs seem to come from the intense, hot middle of something. We are dropped in, immersed, sunk deep.

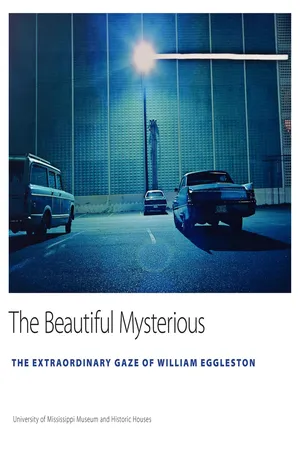

Eggleston has talked about trying to “creep up” on his subjects, and the photographs have that feeling. We encounter these jagged Eggleston worlds just before or just after something perilous or ecstatic has happened. Or both, but what? This brings me to the name of the show, which comes from an Albert Einstein quotation: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.” Of course, the mystery lurks in every busy or barren corner of an Eggleston photograph. That mystery can feel like pathos: the man at the gas station gazing longingly at the liquor store sign glimmering darkly on the horizon. The mystery can feel like menace: the eerie eye-windows of a darkened church door. It can feel like a lot of things at once: the sweep of terrible history, as we might see in the white Winn-Dixie sign with its comic and tragic faces looming above.

Eggleston’s photos encourage the pathetic fallacy—which I’ve never thought of as pathetic at all—an old term we learned in high school English about attributing human emotions to things or objects: a lonely window, a lusty pair of headlights. Eggleston’s photos are so shot through, so infused with mood, with feeling, that they demand the pathetic fallacy. I have always felt, as critic Malcolm Jones writes, that Eggleston “addresses the meanest objects with unstuttering love.” Consider the objects in this show: A lonely pink patio chair, squat and hopeful. A uniform starched on a clothesline, insistent and formal. A dishcloth with holes like eyes. The cluttered front seat of a car, white feathers dangling glamorously from the rearview mirror, promising a world more refined than the plastic McDonald’s cup that’s also there, or the brown paper bag that’s shot through with light. The soulful gaze of a young man with a twin-scoop ice cream cone, seemingly change in hand. Even to describe these photos in sparest terms is to begin a story, but the story is ours. And it begins with feeling, trying to untangle the feeling we feel without knowing why we’re feeling it: loneliness, the expectation, the wonder and longing.

This image of the young man with the ice cream cone drew me so closely the first time I saw it with Marti and Robert in the Museum. For me, it seemed to recall a lost frame from The Last Picture Show, the movie. Every time I look at it, I feel more story and more feeling. He’s well groomed, dressed for a date who never arrived or arrived with someone else. It’s my guess that he has change in his hand. It’s my guess he looks deep in thought. I had this speculation that the twin scoop of the cone bespeaks something—a love lost or never won, a yearning, an aching disappointment. Does the change in his hand come from buying the cone, or is he about to play a sad, sad song on the jukebox we see in another photograph from the show, gleaming and machinelike and substantial? That change he carries as if it were Roman coins, heavy and substantial. Or maybe he’s carrying them lightly, maybe he has not a trouble in the world and the stitch in the brow I think I see is really a mere matter of “Do I pick Sam the Sham or Jr. Walker & the All Stars?” Callow youth! Why am I assuming there’s money in his hand? Maybe he’s snapping his fingers. Maybe. Maybe, maybe.

See how quickly we get lost, subsumed into a narrative waist-high? I was talking with Phil Boyle last night (he’s in the audience), and he said, “That’s the most sinister photo in the exhibition.” Then suddenly I looked at it and thought, “Maybe it is. Maybe this is like Dick and Harry. I don’t know.” At any rate, the story that springs from the photograph could never be the young man’s story, nor Eggleston’s or his magical camera’s. The story is ours. The feeling is ours—spurred, sparked, inflamed by what we see here, the spell cast. “How democratic,” as Eggleston himself might say.

I saw a 1990 interview where Eggleston says about Elvis Presley, “He fits the hole that there never was a hero for.” The journalists point out that Eggleston could just as easily have been talking about himself. He fits that hole that there never was a hero for. There’s something in these photographs we need without ever knowing why. “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious,” says Einstein. “It is the source of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand wrapped in awe, is as good as dead—his eyes are closed.”1 These photos open our eyes. They drive the blood. They kind of ransack the heart. They bring us to the center of something. We feel them. We can’t stop looking. We look again. We close our eyes and still see them. We’re forever seeing them.

So maybe it’ll happen for you today. A photo you’ve seen before perhaps or wondered at or thought you know. Or, more likely, one you’re seeing for the first time. You’ll look at it, you’ll wonder, imagine something, remember something; and by the time you leave, it’ll be a part of you, and it likely always was. Maybe, then, it’s not we who might come to understand these photographs, but they who’ve always understood us, speaking to places deep inside. Years ago, Eggleston told an interviewer, “I would love to photograph dreams.” Maybe he has.

Lisa Howorth: Okay. We’re lucky to have Megan to do that lovely introduction to the whole topic. This panel feels weird, I realize, because Bill Dunlap isn’t here! I don’t think I’ve ever been to a panel in this room where it wasn’t the Dunlap show. Something’s wrong. Anyway, it’d be fun if he were here. Which I think I’ve been referring to as the Egg Bowl.

Since we’ve got two Williams or Bills, the Ferris one is Billy, and I may refer to Eggleston as Bill or Egg in case you get confused because that’s what some people might do anyway, just to avoid confusion. Here’s our charge: “This panel presents a unique opportunity to approach William Eggleston from the perspective of those who have known him personally over an extended time and from those whose work has been significantly influenced by his images.” That’s what we’re going to try to stick to, and other things will be discussed during the afternoon session. I will ask each of our panelists a question, or just throw something out, and they’ll have maybe ten minutes to answer, and I’ll go around again so each panelist will have roughly two questions. We’ll see what happens. Maybe at the end we’ll have time for a Q&A or maybe some Eggleston anecdotes. I’m sure there are plenty of those out there.

First let me say about myself that my credentials for being on the panel are I’m old enough to have known Bill for about thirty years, which is saying quite a lot. He was coming to Oxford frequently when Richard and I a...