![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A Taylor Made Star

Molding Taylor’s Star Persona

ROBERT TAYLOR CAME TO PROMINENCE IN THE MID-1930S, A TIME when America was coming out of the Depression and Hollywood had just implemented the Production Code (Balio, 1993: 61). It was also a period of peace between World War I and World War II. Taylor’s early star persona as an educated, middle-class American suited this period of newfound prosperity. His screen characters were usually either rich layabouts (Magnificent Obsession), trainee doctors (Society Doctor [George B. Seitz, 1935]), or college students (Handy Andy, Private Number [Roy Del Ruth, 1936], A Yank at Oxford), and publicity material consistently made reference to Taylor’s own background as a doctor’s son and recent college graduate. Taylor’s affluent background and the roles he was given allowed him to distinguish himself from MGM’s other leading man of this time, Clark Gable, who was more earthy, working-class, and known for playing uneducated but worldly wise men. In contrast, Taylor’s 1930s persona depicted the youthful freshness of a generation who did not take life too seriously, at least not until World War II broke out, and both Taylor’s 1930s film roles and publicity reflect this.

In an early academic study of stars, Edgar Morin (1961) highlights issues concerning not only the cinematic performances of stars but their off-screen lives too, suggesting that fan magazines turn readers into voyeurs because articles discuss both the public and private lives of stars. Indeed, articles and photographs featuring stars “off duty” and “at home”—working in their gardens, cooking, or playing sports—present stars as more human and less godlike (as early cinematic stars had been constructed), no matter how staged these were. As Pramaggiore and Wallis note, “audiences do not just appreciate a star’s performance on-screen; they also consume the public image that a star gradually acquires over the course of a career” (2008: 355). This goes beyond seeing a star’s latest film at the cinema or, for modern stars, buying new releases on DVD or Blu-ray, but also dressing and acting like favorite stars, buying merchandise with a star’s name or image on it, and scanning magazines in hopes of finding articles or photographs of a certain star (for specific examples, see Stacey, 1994 and Barbas, 2001). Pramaggiore and Wallis further suggest that stars “represent ideals of beauty, dreams of wealth, and models of masculinity and femininity” (356), which is potentially why we buy into the idea of stardom even when we know these images are constructed. This also works favorably for the film industry, which can use certain stars’ popularity to lure audiences into theatres and, subsequently, generate more money. Audience members wishing to find out about the “real lives” of stars by reading magazines or books would probably gravitate towards those claiming to be autobiographical and seemingly written by the star him/herself. By talking directly to the reader, such works appear to capture the “real” star most fully, thus satisfying the audience’s wish for information.

Publicity material on Taylor emerged early in his career, with an emphasis on informing (predominantly female) readers about his offscreen (private) life, particularly his availability as a bachelor. Discussing how MGM’s publicity department “captured [the] mystique” in its famous ad line about Clark Gable: “Men want to be him, women want to be with him,” Deborah Nadoolman Landis notes that “Gable’s irresistible persona was no accident; it was the result of a career of carefully written and crafted screen roles chosen for Gable, ushered into life by the studio’s prodigious design and production team, and diligently marketed by MGM. Gable, of course, provided his charm” (2007: xxii). Although there is a lack of evidence in publicity material to suggest that men wanted to be Taylor (particularly at the start of his career), article titles such as “Why Girls Fall in Love with Robert Taylor” (Mack, 1936) strongly suggest that women (or at least girls) wanted to be with him. Furthermore, both the titles and content of these articles help to demonstrate that Taylor’s appeal at this time was more wholesome and innocent than the dangerous eroticism that Gable personified. Mick La-Salle refers to Gable as “the most sexually dangerous [of] the dangerous men of the pre-Code” (2002: 132) and, although Taylor was presented as somewhat of a rival to Gable, he was marketed as more of an All-American romantic ideal, similar to but different from James Stewart, who also signed with MGM around the same time as Taylor. Taylor and Stewart’s early images were perhaps a direct result of the impact of the Production Code and the subsequent “cleaning up” of Hollywood, and therefore of its stars.

Mark Glancy suggests that fan magazines, along with critical reviews, fan clubs, promotional materials (including posters and postcards), and other forms of film ephemera, belong to what [Annette] Kuhn has termed “a cinema culture thriving off the screen and outside the doors of the picture palace.” Furthermore, he proposes that Picturegoer magazine was an important, if not central, part of Britain’s cinema culture away from the screen (2011: 455). First published in 1913, by 1939 Picturegoer had become Britain’s longest running and most popular magazine, attracting around 500,000 readers per issue (Glancy, 2011: 455). During the 1930s, the magazine primarily became about “inside information” about stars’ background, career paths, and private lives, giving readers a sense that they were close to the stars (Glancy, 2011: 457). Glancy suggests that viewing Picturegoer in retrospect as a historical source shows Britain’s “diverse film culture,” where “stars figured much more prominently than individual films.” Furthermore, he notes that while Picturegoer is now sold as an artifact of cinema’s “golden age,” the publication inspires nostalgia less than it “serves as a reminder of the complexities of the past, and the challenges of rediscovering the disposition, attitudes and opinions of historical audiences” (2011: 474).

TAYLOR’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY (PICTUREGOER, 1938)

In the summer of 1938, Picturegoer ran a six-part article on Taylor which they claimed was autobiographical. Although it is doubtful that Taylor actually wrote these words, the article nonetheless provides a good starting point for understanding how his off-screen persona was being constructed early on, as well as highlighting the fact that Picturegoer thought it profitable to run Taylor’s life story (all twenty-seven years of it) across five issues. Additionally, analysis of the article allows us to trace which elements of Taylor’s persona were established almost instantly, which remained consistent, and which appeared or disappeared over time. Firstly, to put the autobiography into historical context, it was published in 1938 at the midpoint of Taylor’s first decade at MGM. By the end of 1938, Taylor had appeared in twenty feature films and, most notably, had starred in Camille with Garbo and in His Brother’s Wife (W. S. Van Dyke, 1936) with Stanwyck, whom he married in May of 1939. Although Stanwyck is briefly mentioned across the installments, and features in some of the accompanying photographs, the article sets out to present Taylor as an ordinary, available bachelor with small-town ideals, but one who also happens to live in Hollywood and stars in major motion pictures. Even before breaking the story down into its individual installments, key themes become apparent due to the repetition of certain words throughout the article.

The ordinary/extraordinary binary dominates most strongly through the repeated use of “Nebraska/home” and “Hollywood/work.” In installment one alone, Nebraska is mentioned six times, with a further eighteen references to home (also Nebraska). In parts two to four Hollywood takes priority, with twenty-eight mentions, but Nebraska also receives a further ten references. Reflecting on Taylor as an available bachelor, discussions of his mother also dominate, with her being mentioned thirty times overall, half of these occurring in part one alone. Other central areas of discussion are his late father (twenty-two references), MGM (seventeen references), college (sixteen references), and acting (fourteen references). Combined, these individual elements create a clear but balanced divide between the “real” Taylor (Nebraska, college, and his parents) and his constructed persona (Hollywood, MGM, and acting).

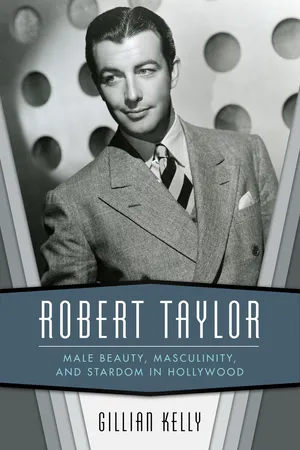

The first installment of Taylor’s life story was published as a two-page feature on July 23, 1938, accompanied by a full-color photograph of Taylor as the magazine’s cover star. Featured in close-up and in profile, the image depicts Taylor as a smartly dressed young man, in a pinstriped suit, spotted tie, and fedora hat. His dark hair is short and neat, and his face somewhat relaxed but positioned to show off his profile. Above the magazine’s title, readers are promised the “real” story of Taylor’s life—“My Life Story by Robert Taylor”—while the article, “Robert Taylor Tells All,” continues this theme by announcing the “inside story” of Taylor’s life from the actor himself. The accompanying photographs show Taylor hugging his mother as Stanwyck looks on; his being fitted for a suit by a Hollywood tailor; wearing a cowboy outfit while on horseback and talking to “Fiesta queens” at the San Fernando Fiesta; and an image of him as a child.

The cover image, content of the article, and accompanying photographs combine to present Taylor as a star who strongly embodies the ordinary/extraordinary paradox proposed by Dyer (1979) and John Ellis (1992) as being essential for revealing stars to be like us (ordinary), while also possessing a special uniqueness which makes them a star (extraordinary). Through the images alone, it is obvious that Taylor is being presented by Picturegoer in just such a way. Ordinariness is conveyed through his hugging his mother, talking to girls, and trying on a suit, while extraordinariness is shown by movie star Stanwyck observing him, a Hollywood tailor dressing him, and his being presented as extremely good-looking. Additionally, the baby picture allows readers a glimpse into Taylor’s personal photographs and, thereby, to share in a private moment with him. Although the candid nature of the photographs suggest naturalness, they are still used (like studio portraits) to “sell” Taylor as a specific star image.

The article opens with Picturegoer promising readers “one of the scoops of the century” as Taylor reveals secrets about “his early years and his arrival in Hollywood” (1938a: 7). Since the words of the article are attributed to Taylor, I refer to them as such throughout the analysis, although I acknowledge here that it is unlikely that he actually wrote the article. Taylor’s opening words—“I haven’t lived my life yet … but I’m willing to try to write it”—demonstrates that current debates around stars writing their autobiographies at a relatively young age is not a new phenomenon. Furthermore, he sets the article up like a fairy tale or fictional work, rather than an account of his real life, by initially stating that “since this is a story, perhaps it had better have a beginning” (6). The theme of niceness, which became associated with Taylor instantaneously, is evident within the first few paragraphs when he states that the main reason for writing the article is to inform readers about the “splendid people” who helped him along the way. Subsequently, he names Greta Garbo, his parents, his cello teacher, Louis B. Mayer, and Will Rogers as key figures, along with “scores of other interesting people in the story” (his second use of “story”). Throughout the article the ordinary/extraordinary paradox again prevails, reflected in discussions of Nebraska/ordinary (“the grain fields”) and Hollywood/extraordinary (“the brilliance of Hollywood”).

As McLean notes, it is not unusual for articles to reference a star’s “humble origins [since] they form part of Hollywood’s continual invocation of the American Dream as a narrative about moving from obscurity to stardom” (2004: 45). But the account of Taylor’s ordinary beginnings also has elements of the extraordinary located within it. For example, his grain-merchant father becoming a doctor to cure Taylor’s ailing mother (similar to the plot of Magnificent Obsession); overcoming a bad childhood stammer (brought on by trying to say complicated medical terms at an early age) to win public speaking awards; and his birth name of Spangler Arlington Burgh (apparently named for the hero of a novel his mother read while pregnant). Anecdotes of Taylor’s “humble” beginnings help to demonstrate his unusualness from an early age, despite the fact that his off- and on-screen star personas were consistently grounded in ordinariness throughout his career. Despite indications that Taylor never considered acting as a career—he instead contemplated becoming a doctor, lawyer, teacher, or musician (all of which he would later play onscreen)—there is repeated foreshadowing about Hollywood.1 One anecdote notes a local factory owner predicting that Taylor would make films one day; another mentions his acting in a high school production of Camille (he would later star in a film version); and yet another suggests that he was only put “in the vicinity of Hollywood”—somewhere he had never given any thought to—after following his music teacher to a new academic institution. The story of Taylor not being accepted at the new college, proving his worth, and eventually making friends is similar to the plot of A Yank at Oxford, released the year the article was published.

Also similar to the plot of a film is the recollection of his being discovered by an MGM talent scout attending one of his college plays. Details of Taylor’s MGM screen test include his initial arrival at the studio: “my heart was pounding … I thought I might catch sight of Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford or Greta Garbo” (7), which sounds like something readers might experience in the same situation, allowing them to identify more easily with Taylor. Within the next few years, he would have starred opposite all three women: Shearer in Escape (Mervyn Le-Roy, 1940), Crawford in The Gorgeous Hussy (Clarence Brown, 1936), and Garbo in Camille. At the time the article was published, he was yet to appear with Shearer, but readers would most likely be aware that he had since starred opposite Crawford and Garbo. Furthermore, the anecdote provided free publicity for MGM and its top female stars. Showing an ability to craft a performance to fit a role, Taylor analyzes his own screen test at length. Although he begins by stating “I tried to restrain myself from over-emphasizing the emotional scene,” he concludes that “when I was finished, I was glad to settle for the mere survival of the ordeal,” further highlighting the ordinary/extraordinary tension and once again connecting him to the reader (7). The installment ends with the promise of his employment at MGM (with the reader aware that Taylor was both employed by the studio and extremely successful there), revealing that in the next issue Taylor will discuss the construction of “Robert Taylor” as a star persona: “I start to learn to act, and also change both my name and my appearance” (7). Thus, it seems that Burgh, the “real” man, is confessing to the reader that the star “Robert Taylor” is a construction of MGM, which changed his name, taught him how to act, and altered his appearance to help him fit Hollywood’s expectations, which is, of course, an accurate summary of stardom and star personas more generally.

The headings of the subsequent installments—“I Make the Hollywood Grade” (July 30), “Hollywood from the Inside” (August 6), “I Introduce Myself to My Fans” (August 13), “Greta Garbo Thrilled Me” (August 20), and “What I Thought of England” (August 27)—relate little to the content of the pieces, with most subjects in the titles appearing as only passing references. The articles are, instead, a series of anecdotes about Taylor’s past and present off-screen life, combined with details about the process of making films in Hollywood and presented from an “insider’s view” that is shared with the reader.

Part Two, “I Make the Hollywood Grade,” opens with Taylor critiquing his work with MGM drama coach Oliver Hindsell, noting the “excessively dramatic” lines of dialogue he was asked to read. Further analyzing his performance by suggesting that he could not have “crowded a great deal of technique” into the part, given the nature of the lines, Taylor suggests that it was probably “as much a personality test as anything” (1938b: 6). College is again mentioned, along with the date of his graduation (June 9, 1933) and the agreement he had with his father that if he did not “make good” after a year in Hollywood, he would return to Nebraska to find work there (6). The consistent link to hard work is highlighted when Taylor announces that “idleness is not helpful to an actor,” followed by details of his “becoming” Robert Taylor through a makeover and change of name (to one more easily remembered). Taylor thus decisively demonstrates his own lack of idleness. Details of his new look merely include a new wardrobe (“an actor should dress well—a great deal depends on it”) and a trip to the barber (who “changed the parting in my hair and trimmed it a bit differently”). He concludes that this made an “immense” change not only to the way he looked but gave him “confidence and courage” (6). This further helps to “sell” both Taylor and the right clothes as commodities, and thus as two different kinds of consumption for the reader; so does the image of him being fitted for a suit from Part One (for more on stars and audience consumption, see Eckert, 1991). Yet, he also notes that “the ambitions of Robert Taylor did not at once start towards realisation” because of the sudden illness and subsequent death of his father in late 1933, which made him seriously consider returning to Nebraska permanently in order to care for his sickly mother. Going back home, Taylor began working at an oil station despite still being under contract to MGM; this again demonstrates his work ethic and continued dedication to his mother. The list of jobs he held while studying (including working as a bank clerk, in an auto paint shop, shocking wheat, and mowing grass) further emphasizes this. This adds to Taylor’s normalcy and ordinary appeal, again connecting him to the reader since, despite a privileged background as a doctor’s son, he held down a number of menial jobs which may coincide with the socioeconomic demographic of the readership. Noting that his mother convinced him to return to Hollywood on the understanding that she would accompany him, he signed a long-term contract with MGM on February 6, 1934. Describing his childhood love for Westerns, and his father’s amusement when he imitated stars such as Tom Mix, Taylor concludes, “I still feel a hankering to do something of the blood-and-thunder sort” (and he would, but not for a while). This installment ends with Taylor stating that although Hollywood had slightly altered him, “the foundation remains the same. Even to-day I pinch that actor Robert Taylor and find that it hurts the fellow from Nebraska, Spangler Arlington Burgh.” This again shows the distinction between Taylor (the star) and Burgh (the “real” man) and his being able to remain the same at the core, which became key to his star persona over time.

The third installment begins with Taylor discussing his first notice, for Society Doctor (1935), which he calls “a special spiritual satisfaction for me” since he could borrow some of his late father’s “compassion to the practice of medicine” to play the role of a doctor. This suggests that, by channeling his own father’s dedication to his profession, Taylor was able to portray a believable doctor on-screen, thereby giving his performance a sense of authenticity. Taylor is defensive about the latter half of the notice though, which states that he “gave a good account of himself in spite of his matinee idol looks.” Suggesting that looks are a matter of taste, Taylor adds that “my appearance doesn’t fascinate me, but I’m not the one who has to be pleased,” and that “it’s a big help to an actor if people like to look at him, but it has nothing to do with acting” (1938c: 4). Thus, it appears that Taylor felt looks and acting ability are two completely different things and that, while looks are important for screen stars, they cannot replace acting talent. Furthermore, he suggests that good looks can “operate to a person’s disadvantage” and, while he does not expand on what he means by this, we can assume that he is referring to the negativity of the notice which belittles his acting ability simply because of his physical appearance.

Discussing his private life, Taylor notes that it was his mother who suggested that he move out and “set up bachelor’s quarters” (4). Mentioning a love for eating out, but adding that his tastes are simple because he still has “the attitude of a Nebraska harvest hand,” Taylor says he prefers “good beef and potatoes or beans [to] such trifles as caviare.” The ordinariness of this statement, however, is juxtaposed with his favorite topic of conversation at dinner: “making movies. Nothing else interests me as much”; and his favorite places to eat adds a further contradiction: the exclusive Brown Derby and “a drive-in sandwich stand” close to his house (5). Demonstrating his ability to get along with people at all levels, Taylor talks about mingling with fellow actors as well as prop men an...