eBook - ePub

Where Rivers and Mountains Sing

Sound, Music, and Nomadism in Tuva and Beyond, New Edition

Theodore Levin, Valentina Süzükei

This is a test

Share book

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Where Rivers and Mountains Sing

Sound, Music, and Nomadism in Tuva and Beyond, New Edition

Theodore Levin, Valentina Süzükei

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Theodore Levin takes readers on a journey through the rich sonic world of inner Asia, where the elemental energies of wind, water, and echo; the ubiquitous presence of birds and animals; and the legendary feats of heroes have inspired a remarkable art and technology of sound-making among nomadic pastoralists. As performers from Tuva and other parts of inner Asia have responded to the growing worldwide popularity of their music, Levin follows them to the West, detailing their efforts to nourish global connections while preserving the power and poignancy of their music traditions.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Where Rivers and Mountains Sing an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Where Rivers and Mountains Sing by Theodore Levin, Valentina Süzükei in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Ethnomusicology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Ethnomusicology1

FINDING THE FIELD

ROAD WARRIORS

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO: FEBRUARY 1999

Santa Fe’s well-burnished charm has eluded the Days Inn on Cerrillos Road, just off Interstate 25 near the southern edge of town. It’s classic Strip Motel. If you check in after 9:00 PM, the front lobby is locked, and you slip your credit card to the night clerk through a slot under the bulletproof window punched in the adobe. Around back, the doors to the guest rooms hang a little crooked in their frames. Daybreak illumines ghostly, naked vines that grip a chainlink fence surrounding a swimming pool filled with stagnant brown water. This is the sort of roadside joint whose rock-bottom rates perfectly suit the four members of Huun-Huur-Tu, the music ensemble from Tuva that has been throat-singing its way around the world since 1994 and has now come to Santa Fe to croon Tuvan melodies in a night spot called the Paramount. I am along for the ride in the loosely defined role of group ethnographer, compact-disc flogger, and tour manager emeritus, having happily ceded active duty to my friend and former assistant, Alexander Cheparukhin, who oversees Huun-Huur-Tu’s extensive tour schedule from an office in Moscow.

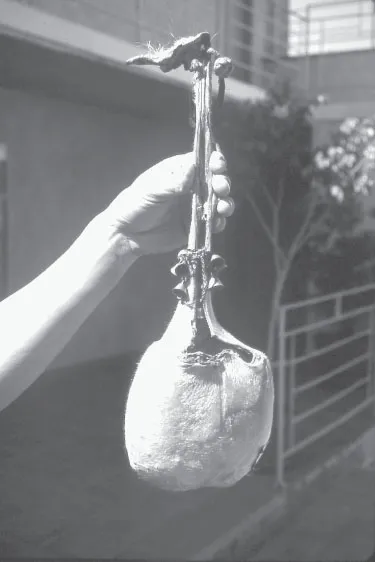

The Paramount has been open only a short time and the Santa Fe promoter has worked valiantly to publicize Huun-Huur-Tu’s appearance. But as the concert begins, there are empty rows of folding chairs in the back of the room. The Tuvans, though, are not the evening’s main attraction. The star of the show is a local diva named Laura Rodriguez, who has just released a new compact disc. Rodriguez is going to follow Huun-Huur-Tu, and halfway through the Tuvans’ first set, her fans begin to show up and noisily wait for the strange music from Siberia to end. A commotion around the buzz-shorn, handcuff-equipped security men standing watch at the front door announces Rodriguez’s arrival in a white stretch limousine. Dressed in seamless hip-to-toe leather and a gold top, she kisses and hugs everyone at the door as she sweeps into the club. Rodriguez appears not to notice the four musicians in exotic silk robes onstage, who make unearthly sounds with their mouths and play instruments such as the igil, the doshpuluur, and the xapchyk, a rattle made from sheep’s knee bones sewn inside a bull’s scrotum.

The sound engineer, a young man named Alex with a shaved, perfectly ovoid head, is puzzled and a little frightened by Tuvan music. What is it supposed to sound like and how should it be programmed on his big mixing console? To make matters worse, one of the microphones is on the fritz, and Huun-Huur-Tu threatens to stop the concert in the middle of a song. Abrupt gestures and anxious faces transcend the language barrier. Several songs later, the microphone problem is fixed. At intermission, Tuvan music fans near the front clap loudly as the musicians slip away to their dressing room, which doubles as the club’s kitchen. Sayan Bapa, who speaks a little English and is Huun-Huur-Tu’s liaison to the English-speaking world, hysterically curses the sound engineer in Russian. “If that guy doesn’t stop fucking our brains with the sound, there’s not going to be a second set. Go and do something about it!” he orders me sternly.

As 10:00 PM approaches, the house manager paces nervously. Laura Rodriguez’s fans fill the entrance foyer, line the front bar, and stream down the long corridor to the back bar. The club is reaching capacity, and in order to let more people in, the audience listening to Huun-Huur-Tu has to be moved out.

The house manager confronts me. “When are they going to finish?” he barks.

“Two more songs,” I reply.

“Are they long?”

“One is, one isn’t.”

The last song ends, but the Tuvan music fans offer so much applause that Huun-Huur-Tu returns for an encore. The house manager clenches his teeth and narrows his eyes. Then it’s finally over. Stage equipment is hastily rearranged for Rodriguez’s set, and the Paramount is once again its usual self. The evanescent sounds from Siberia have touched some listeners and passed through others without leaving a trace. A few fans approach the members of Huun-Huur-Tu for autographs. “Hope you’ll come back to Santa Fe soon!” chirps a young, ponytailed well-wisher as the Tuvans sign her newly purchased CD.

“Sure,” says Sayan. “We hope so, too.”

Xapchyk, a Tuvan percussion instrument consisting of sheep knee bones inside a bull scrotum.

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA: MARCH 1999

We rent a Jeep Cherokee at the airport, and Tolya Kuular takes the wheel, even though he’s not allowed to be an official driver because he doesn’t have a credit card. Jeep Cherokees have a lot of cachet in Tuva, partly because jeeps are ideally suited for Tuva’s rough roads but also because of their infamous role as a favored vehicle of the Russian Mafiosi. In the boom years of the new Russia, Mafia tycoons were typically followed in their Mercedes or BMWs by bodyguards driving Jeep Cherokees with smoked windows.

Tolya has tractor-trailer and bus driving licenses, and he worked as a professional driver in Tuva before he became a fulltime musician. Los Angeles freeways don’t faze him. He is one of the most competent drivers I’ve ever met, and he navigates the complex traffic patterns with complete assurance, somehow assimilating the welter of highway signs written in an alphabet he can barely read and invariably responding correctly.

We are headed to Valencia, where Huun-Huur-Tu has a two-day residency at the California Institute of the Arts. An afternoon workshop has been arranged with student composers to explore how Tuvan throat-singing might serve as a resource for cutting-edge electroacoustic music. Two students are preparing to demonstrate a computer-based program for sound processing that they have developed for the occasion. The Tuvans’ singing triggers filtering mechanisms run by the computers that create reverberant sound loops and metallic-sounding drones. These loops and drones are fused with the source sounds, and the whole clamorous cacophony is amplified through speakers. One of the student composers explains to the Tuvans what’s going to happen. “We have two computers and one of them is going to take vocal sounds from the microphone and the other will take instrumental sounds. We’ll take your input as it comes into the computer and run it through some filters, and we’ll also be recording ten-second snippets of sound and repeatedly playing them. So there’ll be kind of a sequence thing going on, where there’s some continuous processing and also some repetition.”

At the end, we assess the results. “We didn’t really feel anything,” Sayan says. “We heard some strange sounds, but we don’t understand how they were related to what we’re doing, or what the point is.” The students are not discouraged. It was just a first attempt, they acknowledge, and it would have been more interesting if it had been more interactive.

Following the workshop, some members of the audience linger to ask questions. A rumpled older gentleman stands up and poses a question: “I’ve read that there are old Chinese documents attesting to the fact that in ancient China, music was used as a way of cleansing the inner organs. Are there documents about these kinds of practices in Tuva?”

“The Tuvan language wasn’t written down until 1930,” Sayan replies. “In any case, we don’t need documents to tell us about our music. What we do comes naturally to us.”

Later, Sayan remarked that it had been a good workshop. “They were normal people. They didn’t want to touch us, feel up our chests, look down our throats. They just enjoyed the music and tried to appreciate what we’re doing. Why is it that people always want to sing like us?”

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON: FEBRUARY 1999

The members of Huun-Huur-Tu are the last to board the flight to Denver. The ticket agent asks whether my traveling companions understand English, and when I shake my head, she says apologetically that they must be asked the two security questions in their native language. I volunteer to translate, but the agent looks insulted. “Sir, if I allow you to ask those questions, I could lose my job. I’ll have to request an authorized interpreter. What is their native language?” I tell her that their native language is Tuvan. Showing no reaction, she dials a phone number.

“I need a Tuvan-speaking interpreter to do a security check,” she says.

There is a pause, and then she asks me, “Sir, what language is Tuvan similar to?”

“Xakas and Altai. It belongs to the Oghuz branch of Eastern Turkic.” Another pause.

“Sir, do they speak any other language?”

“Russian.” The ticket agent remains expressionless, but evidently there is action on the other end of the line. A few moments later, an émigré named Volodya is chattering with the members of Huun-Huur-Tu, and somewhere in the conversation he throws in the questions about whether they packed their own bags and whether anyone has given them items to carry. When it’s over, I ask the ticket agent what would have happened if my companions had not been bilingual in Russian.

“They wouldn’t have been allowed to board,” she replies curtly. Trying to put a human face on the matter, she adds, “If there had been enough time, we could have used other means to get the answers.”

On board, a young man in the aisle seat in front of me turns around and asks whether my companions are from Tuva. “I’ve been to Tuva,” he says. “In 1993, I rode a bicycle through the west of Tuva with a couple of friends from California. Awesome trip.”

MOSCOW: AUGUST 2003

For centuries, the principal trade routes from Tuva pointed southeast, toward Mongolia, and beyond to China. These days, however, Tuva’s links to the world beyond the Altai-Sayan Mountains run north and west—to Abakan, Krasnoyarsk, and Novosibirsk. It’s difficult to go far without transiting through Moscow, and Huun-Huur-Tu has logged a lot of time there. I have arranged to arrive in Moscow on the same day that they are flying in from a concert in Copenhagen, and we agree to meet near Red Square for a leisurely stroll in the damp evening air.

In front of the TASS Building, a policeman carrying a semiautomatic weapon steps out of the shadows and blocks our path. Saluting, he commands crisply, “Your documents, please!” The Tuvans calmly extract Moscow residence permits from their wallets and hand them to the policeman. He scrutinizes their faces, then the papers, and then looks at their faces again before returning the papers without comment. I hand the policeman my passport and immigration form, which on the reverse side had the hotel registration stamp I received earlier in the day.

“Your registration is invalid,” says the policeman. “It has to be issued not by the hotel, but by the Office of Visa Registration. You’ll have to come with me to the police station and pay a fine. I have the right to hold you for up to three hours.”

The policeman’s scam triggers an instant response from Sayan. “Perhaps the American could pay the fine on the spot, and avoid having to go the police station,” he says in a conciliatory tone.

“I’m not allowed to accept payment of fines,” the policeman replies, stonyfaced, serving notice that he is not going to be a pushover. He knows precisely how much it is worth to an American not to spend three hours in a Moscow police station. Sayan does not know that number, but he takes a guess.

“We’re talking about five hundred rubles.”

The policeman shakes his head. “I’ll explain to your friends where the station is, so they can come down later and pick you up,” he tells me firmly. I look at Sayan and jerk my head and eyes ever so slightly upward.

“How about a thousand rubles,” Sayan says softly.

The policeman hands back my passport. “Put a thousand rubles inside the passport and give it to me,” he orders.

It is over quickly. As I stow the passport in its secure pouch while the policeman disappears back into the shadows of the TASS Building, Sayan jabs me in the ribs. “Now you know what it’s like to be an uryuk.”

Uryuk means “dried apricot,” but in Russian army slang, it’s a crude descriptive for soldiers from Uzbekistan, the land of apricots, or just about anywhere else east of the Urals. Huun-Huur-Tu may be well known in the world music emporia of London and Los Angeles, but on the streets of Moscow, where an undeclared war is being fought against Chechen militants, they’re just four more faces from the nebulous hinterlands of Russian Asia. Even with their Moscow residence permits, the members of Huun-Huur-Tu mostly stay indoors during their transits to avoid police checks and confrontations with the local skinheads. “It’s the capital of our country,” Sayan laments, “but we feel like foreigners here. It was almost eight hundred years ago that Russia fell to the Mongols, and some people are still trying to even the score.”

PORTLAND, OREGON: FEBRUARY 1997

The Aladdin Theater, on Portland’s East Side, is a renovated movie hall, and there’s no barrier to the backstage area. You just plunge through a velvet curtain, walk up a flight of stairs, and you’re in the dressing rooms. After Huun-Huur-Tu’s concert, some local overtone-singing luminaries invite themselves backstage to share tradecraft with the Tuvans. Ed and Gloria (not their real names) are both large and bespectacled, and as they approach the Tuvans, their expression is one of reverence mixed with awe. “Thank you for your wonderful music,” says Ed, pressing palms and fingers together in a votive bow.

“You’re welcome,” replies Sayan.

“We also do throat-singing,” adds Gloria. “Would you like to hear us sing?” The syntax of Gloria’s sentences overloads Sayan’s command of English, which was still tenuous in 1997, and I am asked to translate. Without waiting for an answer, Ed and Gloria join hands, screw their eyes shut, and, breathing deeply, emit a nasal, undulating harmonic whine above a fundamental tone that sounds like a buzz saw. The noisy undulations continue for what seems a long time. At the end, Ed and Gloria open their eyes.

“Harmonics have healing powers,” Gloria says blankly. “They can harmonize the body at the cellular level. Did you feel anything from our singing?”

“It’s fine, what you do,” answers Sayan, with studied diplomacy. “But it’s not the same as what we do. If you can heal with harmonics, so much the better, but that’s not what we do. We don’t know how to heal anyone. We’re just musicians.”

VALENCIA, CALIFORNIA: MARCH 1999

We are five weeks into Huun-Huur-Tu’s North American tour, and the Tuvans are showing signs of weariness. Only a week remains before they are to take a plane from Los Angeles to Moscow and then fly on to Tuva. They’ll have a break of around two months before their musical nomadizing starts again in mid-May. During a brief lull in the residency activities at California Institute of the Arts, Tolya Kuular announces that he’d like to go shopping for some gifts he wants to bring to his family. At the neighborhood Wal-Mart, Tolya, Alexei, and Sayan go off in search of binoculars, flashlights, and underwear. Kaigal-ool stays with me in the jeep. We are silent, but I sense that he wants to talk. Kaigal-ool has a sentimental side that occasionally overpowers his habitual reticence.

“Are you thinking about home?” I ask.

“I’m tired of traveling,” Kaigal-ool says ruefully, “but I don’t have any other profession. I don’t know how to do anything except be an artist. I’ve been on the road for twenty years.”

KYZYL

KYZYL, TUVA: MAY 1998

Kaigal-ool Xovalyg eases his well-worn Zhiguli sedan—the Russian version of a Fiat 124—into a parking spot in front of the gritty, puce, brick-and-concrete blockhouse where he lives with his wife, son, and daughter in a three-room apartment on the fifth floor. The climb up the barren stairwell belies the comfortable, if sparsely furnished space that awaits behind the triple-locked double doors. On the living room walls are Kaigal-ool’s musical mementos: concert and publicity posters, a string of backstage passes from festivals around the world, and a letter signed by the president of Harvard University thanking him for his service as a visiting artist.

Kaigal-ool is small, round-faced, and mustachioed, with black hair combed down over his forehead and trimmed in neat bangs—a Tuvan Ringo Starr. The beginnings of a belly stand out on an otherwise taut frame. “It’s America’s fault,” Kaigal-ool said with a hint of bitterness when I jokingly patted his stomach. “Too many McDonald’s. It’s all we can get when...