![]()

1 Voyager

Stormy Weather

Lying face up in my bunk, the uppermost one, I thought about my family and about the voyage we would have to make before reaching Cartagena. I couldn’t sleep. With my head resting in my hands, I listened to the soft splash of water against the pier and the calm breathing of forty sailors sleeping in their quarters. Just below my bunk, Seaman First Class Luis Rengifo snored like a trombone. I don’t know what he was dreaming about, but he certainly wouldn’t have slept so soundly had he known that eight days later he would be dead at the bottom of the sea.1

In The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor, Luis Alejandro Velasco, a seaman in the Colombian Navy, recalled hearing the alarming command, ‘All hands to the Starboard side!’, issued to stabilize a dangerously listing ship, the destroyer Caldas, during a fierce storm in the Gulf of Mexico in 1955. Worrying in his bunk a week before the voyage, Velasco was yet to learn that all those who live together aboard any ship may also, in a catastrophe, die together, although such shared sleeping quarters of ordinary naval seamen may intimate through their very communality that all their occupants are subject to the same forces of nature and chance.

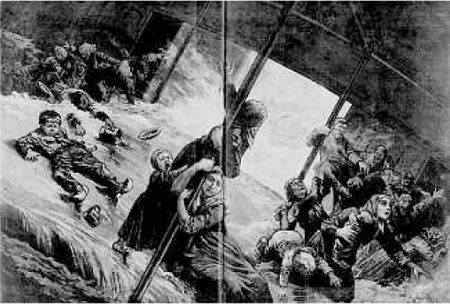

‘Between the decks’ of an ocean steamer in 1885 during a storm.

The inveterate world cyclist Josie Dew offered a less foreboding account of her apprehension regarding the decrepit cargo vessel on which she travelled as a passenger, also in stormy weather:

men and women are destined always to make a small world in the midst of a big one . . . When I’m camping . . . I make a little nest around me . . . because it makes me feel better . . . [And] here we are, on this insignificant lump of rusty metal making a small world in the enormousness of a very watery one . . . We all go about our daily routines . . . Just like on land. And yet we are not on land! . . . Instead we’re bobbing about on the most ancient place on earth – a malicious primal force that plays havoc with human lives.2

According to the philosopher Gaston Bachelard, storms demonstrate the strength of any shelter, while the robustness of that structure enables its occupant to appreciate the aesthetic drama and excitement of the storm. This idea of the protected interior, in relation to the dangerous immensity of the outside, is the single most inescapable fact of the sea-going vessel and a central concern in both its design and interpretation.3

In the earliest days of the transatlantic steamship, Charles Dickens wrote bitingly of his first North Atlantic crossing in midwinter aboard one of Samuel Cunard’s new paddle-wheel liners, Britannia, launched in 1840. Dickens famously described his ‘stateroom’ as a ‘thoroughly hopeless, and profoundly preposterous box’. It failed in every way to live up to the promotional literature displayed at the Cunard offices in London. Dickens compared its two bunk beds to coffins, and he avoided the cabin as long as the weather allowed him to stay on deck or in the public saloons. The primitive design and construction of the wooden ship provided a poor defence against the effects of the storm raging outside. Even with the portholes closed and the hatches battened down, seawater washed freely through the passenger quarters. When seasickness finally took hold, the cabin and the bunk were his last and only resort. Dickens noted that several berths were full of water and all the cabins were leaky. He added that below decks the stuffiness of the air was worsened by a ‘compound of strange smells, which is to be found nowhere but on board ship, and which is such a subtle perfume that it seems to enter at every pore of the skin, and whisper of the hold’.4 Although the historian Stephen Fox has argued that Dickens exaggerated the effects of bad weather aboard Britannia to make a better story for his readers, it remains true that the cabin in a storm was always a dubious refuge for travellers.5

This was confirmed by a young seaman, who travelled through many a storm in the Roaring Forties (an area of infamously turbulent seas in the southern hemisphere between 40 and 50 degrees Latitude) during the early twentieth century. He described the discomfort of the sailor’s wooden berth, the thin, soggy mattress built up at the outer edge by anything that came to hand, coiled rope, clothing or canvas, to restrain the seaman’s recumbent body. ‘We fit down into a V between the mattress and the sidewalls and can’t be rolled out. Even at that, we frequently have to brace ourselves against the upright stanchions to stay in. Frankly, the bunks are about the least inviting spots on the ship.’6

Cramped and leaky, but well upholstered: a first-class cabin aboard an early transatlantic steamship, SS Great Britain.

One hundred years later Josie Dew concurred. This outdoors woman, driven by foul weather to her passenger cabin aboard the container ship Speybank, recorded her attempts to find some peace and quiet in her cabin, where she found the cupboard drawers crashing in and out with each roll of the vessel. Adapting her cycling gear, ad hoc, to the cabin’s built-in furniture, she endeavoured to establish a semblance of calm. She ‘rigged up elaborate drawer-ramming devices involving heavy panniers, gaffer tape and tightly stretched bungees’ and, like earlier sailors, wedged herself against the bunk’s preventer board, trying to sleep, ‘Not an easy thing to accomplish when your body is being jolted about your bunk from one shoulder blade to the other in time with the ship’s violently rowelling jerks and shudders. So instead I lay listening to the howling wind and the rhythmic banging of a nearby door.’7

When Bachelard compares the nooks or corners where we enjoy curling up in our homes to a snail in its shell, he reflects Dew’s attempt to find security and comfort in her spartan bunk, just as Henry David Thoreau found sanctuary in the smallest and simplest of huts, his built on the edge of Walden Pond as a refuge from the nineteenth-century world. There, he extolled the virtues of ‘economy’ and, like Bachelard, the close fit between occupants and cabins, ‘whose shells they are’.8 Thoreau described his house as ‘a sort of crystallisation’ around him, and when the winter storm raged over the pond outside, he sat behind the securely closed door and enjoyed its protection.9

While Dew described a relatively chaste adventure at sea, the novelist Evelyn Waugh exploited the North Atlantic storm as a catalyst for romance aboard the largest, fastest and most popular liner of the 1930s, Queen Mary, bound for England from New York. In Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1945), the central character, Charles Ryder, falls in love with a woman who, like himself, resists the effects of seasickness while most other passengers, including Ryder’s wife, are confined to their staterooms. Ryder describes his effort to sleep in the large bed of a palatial first-class suite:

A sleek modern cabin aboard the fast ro-pax ferry Stena Hollandica, which can carry 300 cars and 900 cabin passengers in considerable comfort.

In a narrow bunk, on a hard mattress, there might have been rest, but here the beds were broad and buoyant; I collected what cushions I could find and tried to wedge myself firm, but through the night I turned with each swing and twist of the ship – she was rolling now as well as pitching – and my head rang with the creek and thud which now succeeded the hum of fine weather . . . And all night between dreaming and waking I thought of Julia; in my brief dreams she took a hundred fantastic and terrible and obscene forms.10

The cabin in a storm is portrayed here as a locus of erotic fantasy. The stateroom, like a bedroom in a large country house, connects by corridors and stairs with all the other rooms, public and private, where the object of desire may be found. Yet, aboard a tossing steamship the privacy and separateness of the cabins are made more poignant by the difficulty of negotiating those stairs and corridors. ‘We were both weary; lack of sleep, the incessant din and the strain every movement required, wore us down.’11 Yet the intimacy found during the storm in the ship’s private cabins and grand, empty public rooms heightens the lovers’ sense of isolation from the rest of the shipboard community:

We dined that night high up in the ship, in the restaurant, and saw through the bow windows the stars come out and sweep across the sky . . . The stewards promised that to-morrow night the band would play again and the place would be full. We had better book now, they said, if we wanted a good table. ‘Oh dear’, said Julia, ‘where can we hide in fair weather, we orphans of the storm?’ I could not leave her that night, but early next morning, as once again, I made my way back along the corridor, I found I could walk without difficulty; the ship rode easily on a smooth sea, and I knew that our solitude was broken.12

Economy

While the 1840s had seen the development of the transatlantic steamship as a viable technical and commercial proposition, led by the engineering innovation of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the entrepreneurial talent of Samuel Cunard, during the following fifty years the ocean liner evolved toward its mature form. And during those years steamships serviced the greatest voluntary migrations in human history, first from the ports of northern Europe and later from eastern Europe and the Mediterranean to the ports of North America, South America and Australia. During those five decades, when the North Atlantic passenger route was busiest, the ships that provided that shuttle service grew continuously in size, power and sophistication. These were the largest moving objects yet constructed and the most ambitious technical achievements of the Industrial Revolution.

Brunel’s Great Britain, launched in 1843 and dubbed the world’s first ocean liner, was a marvel of its age and by far the largest ship of the time at 98.15 m (322 ft) and 3,675 tons. Its first crossing to New York took just fourteen days and twenty-one hours at an average speed of 9 knots. The ship’s innovative iron clinker-built hull was constructed with five watertight bulkheads for safety, and this was the first vessel with a balanced rudder for easy handling. Powered by a 1,000 horsepower engine turning a six-bladed propeller, the Great Britain was also rigged as a six-masted schooner (the first such) for additional speed, stability, security and economy. For comfort, the interiors were richly decorated, and all cabins were steam-heated. The United Service Gazette dramatized its size, calling it ‘the largest vessel that has been constructed since the days of Noah’.13

The ship’s transatlantic service between 1845 and 1847 demonstrated the potential of steam, iron and screw propulsion, but failed, due to a variety of unfortunate circumstances and significant navigational blunders, to achieve satisfactory financial returns for its owner, the Great Western Steamship Company, which became insolvent and sold the ship at auction in 1850. For the next twenty-five years Great Britain served the Australia route, carrying a generation of new emigrants to Melbourne from Britain in response to the Australian Gold Rush. For this purpose, the ship was converted to run as a steam-assisted sailing ship rather than a sail-assisted steamship, since it was not yet possible to bunker sufficient coal for a full run under engine power over such a great distance, a passage lasting around 60 days. Subsequently, the Great Britain made 32 trips to Melbourne, carrying up to 730 passengers in three classes.

On its first Australian voyage in 1852, the American Consul in Liverpool, the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, rode the ship as far as Holyhead Light and reported ‘immense enthusiasm amongst the English people about this ship, on account of her being the largest in the world. The shores were lined with people to see her sail.’14 All this excitement over a ship that was already nine years old and converted from a radical design to a more conventional mode of propulsion!

The period of transition between sail and steam, between the 1830s and the 1860s, was characterized by an intense rivalry between the fast sailing ship, which was reaching its peak of perfection in terms of efficiency, speed and elegance, and the primitive new paddle-wheel steamship, which was experimental. During these years, Bostonian Lauchlan McKay’s treatise on marine architecture, The Practical Shipbuilder of 1839, explained the design of hulls and spars for the fastest sailing ships, while John Griffiths, also from Boston, defined the specifications of the mature clipper hull. The swift clipper ships designed and run by Donald and Lauchlan McKay dominated the lucrative tea trade during these years, when steamships could not yet carry enough fuel for voyages from Europe and North America to the Orient. And unlike the inefficient coal-burning steamships, clippers were cheap to run.

The last word in grace and speed under sail, the clipper Red Jacket is pictured off Cape Horn in 1854 by Currier & Ives.

With such sophisticated and economical sailing vessels, Enoch Train and his cousin George Francis Train founded a shipping line that catered to the North Atlantic, Latin America and California trade routes. The McKays designed and built for them the 3,000-ton Enoch Train, the largest clipper of the day when launched in 1852, of which the Boston Daily Atlas wrote: ‘In stowage capacity, strength of construction, and beauty of outline, she ranks the foremost of the clipper fleet. Never was there a ship to which the term beautiful was more appropriately applied.’15 As a result of the Potato Famine in Ireland, annual immigration from Europe to the United States jumped from around 50,000 in 1846 to 300,000 in 1875; and in response these New England entrepreneurs answered this massive demand for cheap passage by outfitting the cargo holds of their economical sailing packets with as many as 400 closely stacked berths. They provided freshwater barrels in the hold plus a cooking shack on deck. Below-deck spaces were dark and badly ventilated. Sanitation was nil. In such conditions, which nearly equated i...