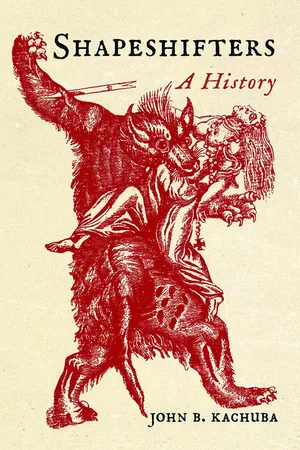

![]()

1

Gods and Goddesses:

Shapeshifters in Antiquity

Firelight illuminates the cave where the shaman squats, working red ochre in his hands. He stands, his flickering shadow looming across the cave. The others watch as his hand moves across the cave wall, daubing on the red pigment. He scoops up more ochre and paints it on the wall, and then stands back to let the others see the bucking, running animals he has painted, the lion and deer, the horse and aurochs. They are held spellbound by the shapes that seem to move in the firelight. They appear lifelike, as though ready to burst from the wall. But one figure captivates them: a human figure that wears the head of a wolf.

There is nothing new about shapeshifters. They have been part of our cultural heritage since the dawn of time. Prehistoric man held a special bond with the animal world, an intimate bond that could mean life or death. That intimate connection is largely lost to modern society, except in some indigenous or ‘primitive’ cultures. Prehistoric man knew the real nature of the animals in his environment, recognizing the strength, speed and cunning they possessed and understanding that he needed to find the means to compete with those abilities in order to survive. So when those ancient cave dwellers watched their shaman draw a wolf-headed man, they knew that in some mystical way, he was invoking the powers of the wolf. By becoming wolflike, a hunter would be more successful and would also be better able to protect himself from animal adversaries.

One of the earliest representations of a figure wearing what could be a wolf mask is an engraving upon a rhinoceros bone discovered in 1928 at the Pin Hole Cave at Creswell Crags in Derbyshire, England. The artefact dates from the Late Upper Palaeolithic era and is believed to be about 12,000 years old.

Animal imitation was not limited to wolves, however, nor was it limited to animal masks. Archaeological evidence from Pin Hole Cave, as well as prehistoric sites in Spain and France, shows the symbolic importance of a wide range of animals, especially bears, lions, foxes, horses and deer. From cave paintings and other artefacts, archaeologists have deduced prehistoric rituals and dance ceremonies designed to invoke the spirits of animals. In such ‘hunting magic’ rituals, animal skins and masks might have been worn and participants might have adorned themselves with the teeth of tigers, bears or wolves. A Neolithic site in Turkey, Çatalhöyük, has cave art depicting men and women clad in leopard skins. Similar figures are found at Cueva de las Manos in Río Pinturas, Argentina, dating from about 7300 BC.

These cave paintings and artefacts clearly demonstrate the importance of hunting animals for the survival of the people, but what did they mean to the individual hunters participating in the rituals? Evidence of natural hallucinogens has been discovered at some prehistoric sites, giving rise to the theory that participants in hunting dance rituals might have been under their influence. If so, a hunter might have believed that he not only took on the spirit nature of the animal, but through hunting magic, transformed into the animal; he became a shapeshifter. It is important to note here that the perceived transformation from man into animal and back again was not within the power of mortal men, but of the shaman and his hunting magic that caused the perceived transformation. This notion that shapeshifting was a power given only to God, or the gods, or their mortal representatives, such as shamans, priests or saints, would be the way people thought about shapeshifters until the Middle Ages.

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics display a number of fantastical creatures, gods who are half-animal and half-human (therianthrophic), gods who are fully animals (theriomorphic) and gods who are fully human (anthropomorphic). The first category particularly intrigues students of Egyptology; here is where one finds jackal-headed Anubis, cat-headed Bastet, ibis-headed Thoth, falcon-headed Horus and crocodile-headed Sebek, as well as the sphinxes with human heads and lion bodies, and hybrids such as Hathor, who is shown with cow’s ears and horns but is otherwise human.

What is not clear is whether the Egyptians believed their gods actually took on those animal forms, or whether they were merely representational, symbolic of the gods’ powers and attributes, similar to Jesus’ association with a lion or lamb, or the Holy Spirit’s with a dove. When Romans first encountered Egyptian religion, the satirist Juvenal wrote, in Satire XV of his Satires, ‘Who knows not . . . what monsters demented Egypt worships?’ Certainly, all three iconographic forms of the gods are widely demonstrated in Egyptian hieroglyphics, statuary, jewellery, and funerary and religious artefacts, but no one form seems dominant.

There is some evidence to suggest the Egyptians did, in fact, believe their gods took on these various forms. While the gods were not themselves the statues found in homes, temples and tombs, they could enter into and inhabit the statues. An inscription from the temple of Horus in Edfu reads, ‘He comes down from heaven day by day in order to see his image upon his great throne. He descends upon his image and unites himself with his cult image.’

The gods could also inhabit humans, as they did with the pharaohs, and could inhabit animals as well. Honora Finkelstein, professor and expert on metaphysics, writes of one such god:

Apis was the sacred bull of Memphis. Supposedly, he was born of a virgin cow impregnated by the god Ptah. A physical bull was worshipped as the son of the god; at the age of 25, the bull would be sacrificed (perhaps in lieu of the sacrificial killing of the king), and a new baby bull was sought to take his place. The cult of Apis came to be so important that Ptolemy 1 introduced the god Serapis, a combination of Osiris and Apis, who was later honored along with Isis throughout the Roman Empire.1

The Egyptian goddess Tawaret, with both animal and human features, Late Period, 664–332 BC.

While these Egyptian gods do not transform from one appearance to another and back again, as traditional shapeshifters, they are sometimes depicted in multiple forms. For example, Thoth could be depicted as an ibis or a white baboon, and the goddess Taweret is often shown as a bipedal female hippopotamus with feline attributes, pendulous human breasts and the back of a Nile crocodile. Transforming or not, these gods and goddesses are powerful reminders of the intimate connection between humans and animals and might be considered precursors to our modern conception of shapeshifters.

It should be noted here that some researchers define shape-shifters more narrowly, only as humans capable of transforming at will into animals and back again while maintaining their human consciousness. That concept is a particularly modern one; nevertheless, it has its roots in these ancient forms and so discussing these various forms of transformations is key to understanding the shapeshifter archetype.

Greek and Roman mythology is rife with stories of fantastical shapeshifting, but, here too, it is the gods who are the perpetrators of such transformations, working them upon the human race. Often the transformation is a permanent one, but there are also cases of shapeshifting that reverts back to human form and even a type of serial shapeshifting in which a human is transformed from one form to another, followed by other transformations into other forms.

In Book VIII of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the river god Achelous entertains the warrior Theseus and tells him of the transformational power of the gods:

O bravest hero, there are many people

Whose form has once been changed, who now remain

In their new state, and there are others, given

The power to change at will, Proteus, for instance,

Who lives in the sea that girds the world, he can

Be a young man, a lion, a raging boar,

Serpent or bull, a stone, a tree, a river,

A river’s enemy, flame.

Achelous goes on to say that he, too, has been a shapeshifter:

I have often changed my own form, let me tell you,

Though I cannot always do it. I have been

A serpent, been the leader of a herd

With all my strength in my horns, but one of them,

As you can see for yourself, is gone.

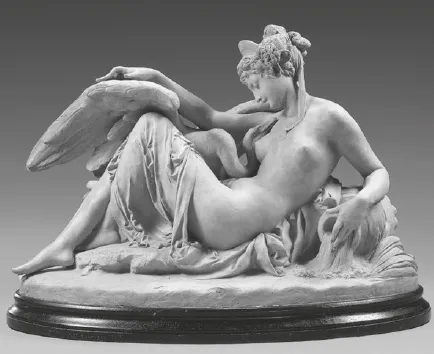

The gods used shapeshifting to achieve various ends. Often the gods transformed themselves into animals or humans to seduce – or, more accurately, rape – female mortals or lesser divinities. Zeus (corresponding to the Roman god Jove) was the champion seducer in this manner, much to the anger and frustration of his wife (and sister), Hera (equivalent to the Roman goddess Juno). A partial list of his shapeshifting seductions includes the following: of Hera herself, in the form of a cuckoo-bird; of Asterie, as an eagle; of Aegina, as a flame; of Mnemosyne, in the guise of a shepherd; and even of an Arcadian nymph, in the form of the goddess Diana. Zeus’ brother, Poseidon (equivalent to the Roman god Neptune), was a runner-up for the crown of shapeshifting seducer, with several conquests including in the forms of a bull, river, ram, stallion, bird and dolphin.

In addition to satisfying their lust, the gods used shapeshifting to avenge wrongs done to them, no matter how petty. In cases in which one god was wronged by another, the injured party would often seek revenge on a hapless human follower of the other god, since one god could not undo the workings of another god. Sometimes the gods used their transformational powers on humans unmercifully, as when the goddess Diana turned the hunter Acteon into a stag simply because he stumbled upon her naked, bathing in a woodland pool. His own hunting dogs ran him into the ground in his stag form and tore him apart.

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, sculpture depicting Leda seduced by Zeus in the form of a swan, c. 1870.

Ovid writes of how the depraved Lycaon murdered a messenger, cut up his body, boiled the parts and served them to Jove, who was disguised as a mere mortal. For this heinous act, Jove turned Lycaon into a wolf:

Foam dripped from his mouth; bloodthirsty still, he turned

Against the sheep, delighting still in slaughter,

And his arms were legs, and his robes were shaggy hair,

Yet, he is still Lycaon, the same grayness,

The same fierce face, the same red eyes, a picture

Of bestial savagery.

Lycaon becomes one of the earliest recorded werewolves, if not the first; the condition of being a werewolf, lycanthropy, derives its name from him.

But the gods weren’t always vindictive, and sometimes transformed people in sympathy for their plights or to help them escape bad situations, as when the river god Peneus turns Daphne into a laurel tree to prevent her imminent rape by Apollo.

In these ancient tales, shapeshifting was a power reserved for the gods and their special representatives among the people. Wielding this power allowed the gods to play out a cosmic chess game of sorts, with poor humanity serving as pawns. As long as the gods jealously guarded the power to shapeshift, mortals had no chance of challenging them.

The shapeshifting motif of the ancient world was not restricted to polytheistic Egyptian, Greek and Roman societies, but crossed cultural boundaries, even to the monotheistic Hebrews. In the Old Testament, in Genesis 19:24–26, God destroys the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, but allows the righteous Lot and his wife to escape, providing they do not look back as they flee. Despite that injunction, Lot’s wife’s curiosity gets the best of her; she looks back and is instantly transformed into a pillar of salt. In the Book of Exodus 3:1–15, God speaks to Moses through a burning bush. Later, in Exodus 4:1–5, Moses asks God how to get the Israelites to follow him as their leader. God tells Moses to cast the staff that he carries onto the ground, where it instantly transforms into a serpent. Moses flees in fear, but God encourages him to come back and take the serpent by the tail, whereupon it becomes a staff again, thereby demonstrating that God’s power could be worked through Moses as leader of the Israelites. In Numbers 22:28–31, Balaam’s donkey speaks to him, chastising the man for beating him. In Daniel 4:33, Nebuchadnezzar is stripped of his kingship and his kingdom for refusing to recognize God, but worse, is transformed into a beast, possibly a werewolf:

The same hour was the thing fulfilled upon Nebuchadnezzar; and he was driven from men, and did eat grass as oxen, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven, till his hairs were grown like eagles’ feathers, and his nails like bird claws.

Angels often took on the form of humans; in the New Testament Book of Hebrews 13:2, one is warned to ‘Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.’

There are passages in the New Testament that seem to illustrate God’s power as a shapeshifter. In Luke 3:22, one reads, ‘And the Holy Ghost descended in a bodily shape like a dove upon Him.’ In Luke 24, the resurrected Jesus joins two of his disciples as they walk to Emmaus, but they do not recognize him; the scripture reads, ‘their eyes were holden that they should not recognize him.’ Why wouldn’t these men, who had spent so much time with Jesus, have been able to recognize him? Could he have deliberately altered his form, his appearance, to test their faith?

Another ancient text points to the remarkable possibility of Jesus as a shapeshifter. In 2012, Roelof van den Broek, professor of the history of Christianity at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, translated and interpreted a Coptic text nearly 1,300 years old held in the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City. According to Van den Broek, the apocryphal stories in the text show the Roman procurator, Pilate, having dinner with Jesus the night before he is executed and even offering to sacrifice his own son in place of Jesus. Such apocryphal stories have been around for a long time, as evidenced by this text, and while they have not been accepted in the canon that comprises the Bible, they were believed true by the people for whom they were originally written.

Hendrik Goltzius, ‘Lycaon Transformed into a Wolf’, engraving from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1589 edn).

But one of the most intriguing passages from the ancient text is one that implies Jesus to be a shapeshifter. The text reads,

Then the Jews said to Judas: How shall we arrest him [Jesus], for he does not have a single shape but his appearance changes. Sometimes he is ruddy, sometimes he is white, sometimes he is red, sometimes he is wheat colored, sometimes he is pallid like ascetics, sometimes he is a youth, sometimes an old man.2

The Jews who had come to arrest Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane needed a way to identify Jesus because of his ability to change appearance, according to Van den Broek. Judas, apparently always able to recognize him, tells the Jews he will identify Jesus for th...