By 1812, Napoleon had consolidated his control of the German and Italian states in western and central Europe, but the Slavic states of eastern Europe remained mostly outside his authority, thanks to Russian refusal to remain part of Napoleon’s continental blockade against Britain. Napoleon’s attempt to rein in his former Russian allies, known as The Russian Campaign and the War of the Sixth Coalition, began the downfall of France’s Grand Empire and its emperor.

Napoleon’s spies had alerted him to Tsar Alexander’s plans to renege on the Russo-French alliance established at the Congress of Erfurt in 1808. Those plans included an attack on France to regain Poland for the Russians. Relations between the two empires had already been strained by Russia’s repeated violations of the Continental System.

In the spring of 1812, Napoleon massed 614,000 men, “an army of twenty nations,” on his eastern frontier. Having made extensive but still inadequate logistical preparations, he faced a choice of invasion routes. Napoleon decided that he and his army’s main body would advance in three columns along an axis from Smolensk to Moscow. The Prussians would guard the northern flank and the Austrians the southern. Napoleon’s inner council urged him not to invade Russia, but he ignored that advice. Indeed, Alexander was aware of Napoleon’s plans and had told the French diplomat Armand de Caulaincourt, “Your Frenchman is brave, but long privations and a bad climate wear him down and discourage him. Our climate, our winter, will fight on our side.”

Napoleon called this invasion The Second Polish War, attempting to justify the attack by invoking Polish fears of an imminent Russian takeover. His hopes to secure the cooperation of Polish nationalists failed because he would not promise them an independent state. This lack of commitment resulted, in Polish atrocities against the French during the winter retreat of 1812-1813.

This invasion has far greater importance to Russian popular culture than to the French. Great literary and musical works about The Patriotic War of 1812 abound. For instance, Leo Tolstoy’s 1869 novel War and Peace is the best-known fictional depiction of that campaign. The Year 1812 by Pyotr Tchaikovsky, popularly known as the 1812 Overture, celebrates the Russians’ victory over Napoleon’s invaders. The memory of this battle remains a potent force in Russian politics. In 2012, the 200th anniversary of Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia, while campaigning for his third term in office, current Russian President Vladimir Putin referred to the Battle of Borodino as symbolic of Russian unity. Later in the year, Putin witnessed thousands of actors reenact the bloody battle. Meanwhile, as part of that same anniversary commemoration, Patriarch Kirill, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, led a memorial service attended by thousands. What the French experienced 200 years earlier, however, was hardly anything worth celebrating.

In the campaign of 1812, Napoleon and the French advanced, looking for opportunities to do battle with their Russian opponents. The Russians, however, conducted a scorched earth withdrawal, depriving the French of forage from the countryside, an essential element of that era’s military campaigns. Napoleon was credited with the remark (even though it may actually have been Frederick the Great who said it) that an army “marches on its stomach.” In this case, the stomach was empty. Napoleon entered Vilna on June 28, 1812, and delayed his advance for two weeks. Why? Because as a result of desertion and consequences of the summer heat, his army was already down by a third! Russian Field Marshal Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly made a brief stand at Smolensk on August 17, then successfully disengaged. A scorched earth policy was fine to a point, but the Tsar was unwilling to let the French take the holy city of Moscow without a fight. The Russians, now under Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov, made a stand at Borodino on September 7.

In this largest battle of the invasion, Napoleon failed to exploit Kutuzov’s open left flank. He resorted to frontal attacks on the Russian redoubts behind a heavy artillery barrage. The French suffered 28,000 casualties and the Russians 52,000. The Russians disengaged during the night and got away clean. Moscow would fall, but Kutuzov had preserved the Russian army as a viable fighting unit.

Napoleon and his Grand Armée marched into Moscow expecting the capture of this city to mean an end to hostilities, but they were sadly mistaken. Instead, with their army intact, the Russians had abandoned Moscow and set it ablaze, leaving Napoleon with a burnt-out wreck of a prize and little prospect of feeding his army.

After repeatedly trying to negotiate peace with the Tsar, Napoleon finally abandoned Moscow on October 19, 1812. The Grande Armée, now down to 100,000 men, was turned back at Malayaroslavets on the 24th and retreated toward Smolensk. Had Napoleon sent out scouts, he would have discovered that the Russians had withdrawn and a warmer southern route home was possible.

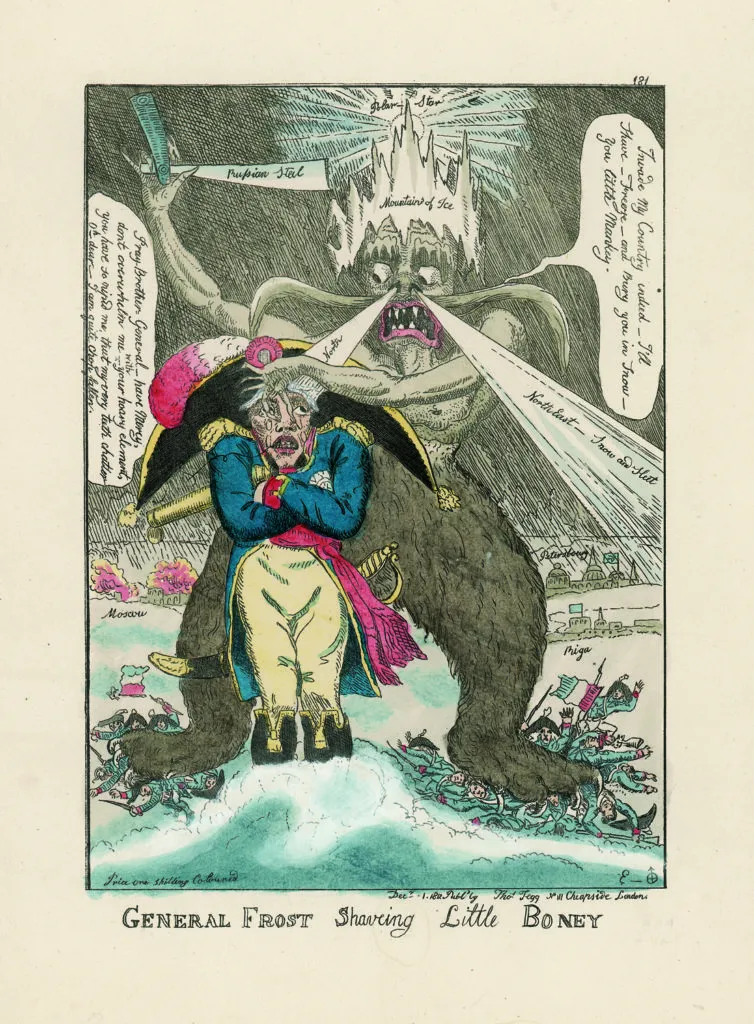

British caricature dated 1812 of ‘General Winter’ defeating Napoleon during his withdrawal from Russia in 1812.

Falling temperatures eroded the strength of the Grande Armée and, with Russian guerrillas on their trail, French soldiers reached Smolensk on November 9. The Grande Armée crossed the Berezina River on November 27-28 with only 60,000 survivors and then ceased to be the Grande Armée.

After so much success, how did Napoleon get to this catastrophic point?

The causes of his downfall began first and foremost with his failure to invade Britain. An 1803 English engraving titled Britannia Correcting an Unruly Boy is a satire on Britain’s fear of French invasion. In this political cartoon, Britannia holds Napoleon across her knee and raises a bundle of birch twigs tied with a ribbon to thrash his bleeding posterior. Britannia says: “There take that and that and that, and be careful not to provoke my Anger more.” Napoleon exclaims: “oh forgive me this time and I never will do so again, oh dear! oh dear! You’ll entirely spoil the Honors of the Sitting.” Placed beside Britannia are her spear and sword; next to Napoleon is his huge hat and saber. The scene is by the sea, with a fleet of retreating vessels flying France’s tricolor flag. On the right is a cliff on which a small British lion lies on a scroll inscribed: “Qui uti scit ei bona,” meaning “good things to him who knows how to use them.” The lion rests atop a cliff overlooking the Channel. Ultimately, this metaphorical spanking of Napoleon by Britannia may have been more consequential to the long-term prospects of Emperor Napoleon’s career than the one his mother gave him while he was a youngster.

Just two years after this cartoon was published, British naval forces under Nelson destroyed the combined French and Spanish fleets. The decisive battle of Trafalgar secured England’s sea power for the remainder of the era, confining Napoleon’s empire to continental Europe only.

Napoleon’s inability to conquer Britain caused him to close European ports to British trade. Not surprisingly, not all of Europe was enthusiastic about damaging their economic opportunities in the service of Napoleon’s imperial ambitions. To stop such opposition in the Iberian Peninsula, Napoleon sent in his armies again. There he faced opposition not just to his economic policies, but also to the French invaders’ alleged atheism.

Officially, Napoleon ruled as a Catholic as evidenced by the Imperial Catechism of April 4, 1807, which can be found at http://www.napoleon-series.org/research/government/legislation/c_education.html and is excerpted here:

Question: What are the duties of Christians with respect to the princes who govern them, and what in particular are our duties towards Napoleon I, our Emperor?

Answer: Christians owe to the princes who govern them, and we owe in particular to Napoleon I, our Emperor, love, respect, obedience, fidelity, military service and the tributes laid for the preservation and defense of the Empire and of his throne; we also owe to him fervent prayers for his safety and the spiritual and temporal prosperity of the State.

Question: Why are we bound to all these duties towards our Emperor?

Answer: First of all, because God, who creates empires and distributes them according to His will, in loading our Emperor with gifts, both in peace and in war, has established him as our sovereign and has made him the minister of His power and His image upon the earth. To honor and to serve our Emperor is then to honor and to serve God himself. Secondly, because our Lord Jesus Christ by his doctrine as well as by His example, has Himself taught us what we owe to our sovereign: He was born the subject of Caesar Augustus; He paid the prescribed impost; and just as He ordered to render to God that which belongs to God, so He ordered to render to Caesar that which belongs to Caesar.

Question: Are there not particular reasons which ought to attach us more strongly to Napoleon I, our Emperor?

Answer: Yes; for it is he whom God has raised up under difficult circumstances to re-establish the public worship of the holy religion of our fathers and to be the protector of it. He has restored and preserved public order by his profound and active wisdom; he defends the State by his powerful arm; he has become the anointed of the Lord through the consecration which he received from the sovereign pontiff, Head of the Universal Church.

Question: What ought to be thought of those who may be lacking in their duty towards our Emperor?

Answer: According to the Apostle Saint Paul, they would be resisting the order established by God himself and would render themselves worthy of eternal damnation.

The Spanish did not share this vision of divine support for Napoleon’s rule. Instead, they responded with a particularly fascinating bit of anti-French propaganda within the question-and-answer framework of a catechism. This example shows both the motives for Spanish resistance to the French and the nature of anti-French resistance:

Question: How is this child named?

Response: As a Spaniard.

Q: What is a Spaniard?

R: An honest man.

Q: How many duties does he have and what are they?

R: Three. To be a Christian of the Roman Catholic faith, to defend his religion, his King and his country, and to die rather than be conquered.

Q: Who is our King?

R: Ferdinand VII.

Q: With how much love should he be honored?

R: With the greatest love, as his virtues and misfortunes have merited.

Q: Who is the enemy of our happiness?

R: The Emperor of the French.

Q: Who is he?

R: A new and infinitely evil ruler, a greedy chief of all evil men and the exterminator of the good, the essence and receptacle of every vice.

Q: How many natural forms does he assume?

R: Two. One a devil and the other human.

Q: How many Emperors are there?

R: There is one true Emperor, with three false faces.

Q: What are they?

R: Napoleon, Murat and Godoy.

Q: What are the characteristics of the first of these?

R: Arrogance and tyranny.

Q: And of the second?

R: Plunder and cruelty.

Q: And of the last?

R: Treason and disgrace.

Q: Who are the French?

R: Old Christians and modern heretics.

Q: What has brought them to this state?

R: False philosophy, and placing liberty above old customs.

Q: How do they serve their ruler?

R: Some feed his arrogance, and others are agents of his iniquity in the extermination of the human race.

The propaganda war conducted during the quagmire in Spain coincided with that drawn-out war...