![]()

PART I

THE THEORY OF METAPSYCHOLOGY

![]()

Chapter One

The Person and the World

In understanding the relationship between a person and the world s/he lives in, it is important to remember that people have different viewpoints. It is well known that when an accident occurs it is rare to find one hundred percent agreement amongst witnesses to that accident. One person thinks car A hit car B; another thinks car B hit car A. One person estimates A’s speed at 35 MPH, another at 50 MPH. It is a difficult task for an insurance investigator, a judge, or a jury to decide which viewpoint is the correct one. The business of compiling and comparing different reports to reconstruct what an “omniscient observer” would have seen at the time is a good and useful activity—in such contexts as that of determining fault in automobile accidents.

In other contexts, however—especially helping contexts, such as teaching or personal enhancement—it is useful to know how people come to see the world as they see it, to understand what conscious and non-conscious actions they take to arrive at a particular view of their world. It is also useful in such contexts to understand what people do to make changes in their world, how they consciously act to create a new environment for themselves. In order to help a person sharpen their perception of the world, for instance, the helper (or “facilitator”) must know what to tell the client to do so as to perceive better. A facilitator therefore needs to know what the client is currently doing in order to perceive, and what the client can consciously do in order to move from his/her current mode of perception to improved perception. It is of no help to a facilitator to be concerned with bodily mechanisms (such as neurological changes) of which the client cannot be directly aware. Rather, the focus must remain on actions of which the client can be directly conscious. When learning how to help someone, it is useful to study the rules that determine how people experience themselves and the world around them. These rules themselves cannot be merely invisible neurochemical mechanisms; they must themselves be evident in the experience of the individual.

Moreover, a person’s view of the world and the objects it contains will very likely change as time goes by. S/he plays different roles; s/he acquires more knowledge and data; the context changes. A person arriving at Disneyland may see a pine tree. On closer examination, that “pine tree” is found to be an elaborately-shaped piece of plastic. So at one point, the person sees a pine tree; at a later time, s/he looks at the “same object” and sees a piece of plastic.

The following questions must be addressed by anyone who truly intends to help someone:

•What are the elements that make up a person’s world of experience?

•By what kinds of actions can a person become aware of existing conditions in his/her world?

•What criteria does a person use to decide which of many possible world-views is valid?

•What criteria does a person use to decide which new conditions to create?

For certain purposes, it is important to judge which view is “objectively” correct. If one were looking for firewood, one would want to know whether a “tree” is made out of plastic or wood. But for the purpose of learning how to help people who are seeking to improve the quality of their lives, judging the correctness or incorrectness of a particular idea is not the crucial issue. What is crucial is to help them examine the process by which they have arrived at such a view and to give them tools for changing that view, if they wish to do so. Likewise, what is important is not judging the correctness or appropriateness of people’s action but helping them look at how they decided to act in that way and, if they wish, helping them find for themselves alternative ways of fulfilling their intentions. Suppose Mary thinks there are green snakes on the wall, that she is causing plane crashes by having “bad thoughts”, or that she can never recover from her husband’s death. From the point of view of providing help, the truth or falsity of these beliefs is not as important as the question of how Mary arrived at them.

The Person-Centered Viewpoint

This person-centered orientation is crucial to the context of personal enhancement and, in fact, to any form of interpersonal communication. The only way of helping another person—or even communicating to him/her—is to change something about his/her world-view. In order to do so effectively, one must first be at least somewhat aware of what the person’s current world-view looks like and one must have some idea of how that world-view came about—from the person’s point of view. To change a person’s world-view, one must take one of two mutually exclusive actions:

- Apply force, duress, deception, or manipulation (physical, emotional, or financial) to get the person to accept the world-view you are proposing.

- Understand why the person has the world-view s/he has and what the person can do to change his/her world-view if s/he chooses.

Under (2) is included:

- Demonstrating facts to the person that s/he can perceive.

- Helping the person to remove duress and force that is impeding or distorting his/her view of the world.

- Helping him/her to acquire skills that s/he can use to change his/her world.

Each of these actions requires that the facilitator (or communicator) be able to see what the world currently looks like to other people and to help them adjust their own worlds in a way that makes sense to them. One cannot change people’s world-view just by pointing out that their world-view is false and exhorting them to correct it. Such invalidation of other people’s views is counter-productive. One cannot usually get others to change their mind just by telling them that they are wrong. To them, their view is not false. One might be able to succeed with a combination of invalidation, force, intimidation, and trickery, but this is hardly a desirable method. Absent the use of force and deception, one must start with what is true for the other person and understand why it is true for him/her, then demonstrate an acceptable way of making the transition from the current world-view to a new one. In other words, one must go about one’s work from a person-centered viewpoint—from an understanding of the present-time viewpoint of the other person and how the person can change it.

Personal Identity

There have been innumerable philosophical arguments concerning the nature of the self. The concept of the self fell into disfavor with modern analytical philosophers like Daniel Dennett (1969), who complained that it was based on grammatical and categorical misunderstandings. Likewise, behaviorists do not speak of the “self” but only of physical behavior. Yet everyone, even a dyed-in-the-wool behaviorist, acts as though his/her own existence were a basic fact of life. Therefore, I am going to accept pragmatically (with the majority) the concept that I exist, you exist, and others exist. For the rest of this book I am going to refer to myself, you, and other people as “persons”. I do this deliberately because I wish to distinguish us definitively from things, such as chairs, mountains, and telephones, that exist but are not sentient.

Assuming we exist, it is fair to ask: “What is our nature?” In attempting to answer this question, the best initial approach is to describe at least part of what a person can clearly see s/he is not. We will not, necessarily, then have a clear idea of what a person conceives him/herself to be. When I enumerate what a person is not, I do not mean to imply that a person is everything else! But we will be closer to understanding what a person is. I have already, by definition, distinguished people from non-aware objects such as tables, chairs, planets, stars, etc. But the question inevitably arises: “What about the body?” and “What about the brain?”

To begin to clarify the issue of personal identity, I give the reader two exercises:

Exercise 1. Change of focus - I

- Read the above two paragraphs with a view to seeing how they align with your experience.

- Now go through them again, but this time notice how each character is formed. Notice the spacing and the typestyle.

- Note the change in focus from the first reading to the second.

Exercise 2. Change of focus - II

- Throw a small object into the air and catch it.

- Do the same thing again, but this time try to notice the exact speed and direction of the motions you are making with your shoulder, upper arm, forearm, wrist, hand, and fingers in executing the motion, and the exact trajectory of the object.

- Were you able to do it?

- Note the change in focus from the first time through to the second.

Focal and Subsidiary Awareness

In any act of awareness, a person has attention focused upon certain things while being aware of other things but not attending to them. When reading a book, I generally attend to the thoughts and concepts and, sometimes, to the words of the writer, but I am not, generally, attending to the letters or to the typographical details, such as the exact shape of the lower-case “a”. Yet I must, in some sense, be aware of the letters and their shapes in order to read the words, and I must be aware of the words in order to understand the concepts. When throwing something into the air, a person generally focuses on the object thrown and the position of one’s hand. Yet one must somehow “take into account” all of the bodily movements used in executing the motion successfully. Awareness that is focused on something is called “focal awareness”. Awareness of something on which a person is not focused, where that awareness contributes to a focal awareness, is called “subsidiary awareness”.1

In Exercise 1, Step (1), you were focally aware of the concepts conveyed by the paragraph and only subsidiarily aware of the letters and their shapes. In Step (2), the focus was shifted to the letters and you became focally aware of them. In Exercise 2, Step (1), you were focally aware of the object, your hand, and their paths through space. In Step (2), the focus was on various parts of your body and their motions. You probably had a hard time catching the object while maintaining this “closer-in” focus in Step (2).

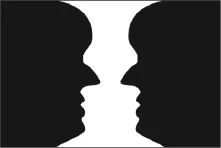

The principle of focal and subsidiary awareness is also well illustrated by the concept of a figure and a ground. Whenever one perceives something, one perceives it against a backdrop of something else. If something else were not there for contrast, the object would be invisible—camouflaged, in fact. A chameleon uses this principle quite effectively. In looking at a picture on the wall, I focus on the picture, but I am also subsidiarily aware of the wall as its ground. The subsidiary awareness of the wall makes it possible for me to see the picture. In some cases, it is easy to shift one’s focus back and forth, the ground becoming the new figure and the figure becoming the new ground.

Try the following exercise:

Exercise 3. Figure and ground

- Look at Figure 1. What do you see?

- Shift the figure and the ground.

- Now what do you see?

Figure 1. Example of a figure and ground

This sort of selection of figure and ground occurs all the time in life, as we shift from one context to another. The figure is what we are focusing on, and the ground is what we are aware of but not focusing on at the moment. In other words, there are two kinds of awareness:

Definition: Focal awareness is awareness of that to which a person is currently attending.

Definition: Subsidiary awareness is awareness of that to which a person is not currently attending, but knowledge of which contributes to an act of focal awareness.

How does this distinction help us to understand what a person conceives self to be at a certain time or what identity a person has at a certain time? A principle that will aid our understanding is one proposed by Michael Polanyi (1962), a physical chemist turned philosopher:

Our subsidiary awareness of tools and probes can be regarded now as the act of making them form a part of our own body. The way we use a hammer or a blind man uses his stick, shows in fact that in both cases we shift outward the points at which we make contact with the things that we observe as objects outside ourselves. We may test the tool for its effectiveness or the probe for its suitability, e.g., in discovering the hidden details of a cavity, but the tool and the probe can never lie in the field of these operations; they remain necessarily on our side of it, forming part of ourselves, the operating persons. We pour ourselves out into them and assimilate them as parts of our own existence. We accept them existentially by dwelling in them.

A person tends to merge with the tools s/he uses to perceive and create and regards them as part of self. S/he regards as outside self that of which s/he is focally aware, that which s/he uses tools to perceive or act upon. In other words, from the person-centered viewpoint, a person is never that which s/he is perceiving or acting upon. A person is separate from that of which s/he is focally aware. From one moment to another, a person may extend, contract, or change that of which s/he is aware. Therefore, at different times, his/her identity may extend, contract, or shift.

Acts of Perception

People use various means of perception. They use each of the senses, but they also use telescopes, microscopes, radio, television, glasses, hearing aids, computer terminals, and the like to perceive the world. If you are skilled in the use of an instrument of perception, it “becomes part of you”, in your experience. Bodily sense organs require no less skill than non-bodily perceptual aids. Acquiring skill in using eyes, ears, nose, tongue, skin, a...