eBook - ePub

Ang Diablo sa Filipinas

ayon sa nasasabi sa mga casulatan luma sa Kastila

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ang Diablo sa Filipinas

ayon sa nasasabi sa mga casulatan luma sa Kastila

About this book

"From his landmark works on nationalism and Southeast Asia to his writings on the Philippines, Anderson has greatly enriched Philippine studies. With work erudite, wide-ranging, and energetically written, he has given to the Philippines visibility in the world of transnational scholarship. His recent essays in New Left Review and Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination—and now the present volume—are not only eye-opening but a joy to read. More than an incursion into scholarship, reading Anderson is an intellectual adventure." —Resil B. Mojares

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ang Diablo sa Filipinas by Benedict Anderson, Carlos Sardiña Galache, Ramon Guillermo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Filosofía & Ensayos filosóficos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Anvil Publishing, Inc.eBook ISBN

9789712731280Topic

FilosofíaSubtopic

Ensayos filosóficos

Top right

Bottom, left

Bottom, right

Nang aco,i, nasa Paombong, ang caibigan cong si Gatmaitan; ay inaniyahan aco sa isang bahay na mayroong katapusan at pinagkakatipunan ng͂ mg͂a dalaga.

Pumayag aco sa caniyang aniyaya at naparoon cami, sa isang bahay na may patay palá…. Tunay ng͂a na isang malaquing piguing, na nacacahauig ng͂ mang͂a pagtotorneo sa Visayas na sinasabi ni Zaragoza. Sa piling ng͂ nababurol ay nang͂ag tatauanang catacot tacot, at pinagsasalitaan nang pagsinta ang mg͂a bulaqueña. Ang mg͂a Visaya, tagalog at ilocano ay nagcacaparis cung namamatayan na ang canilang mg͂a bahay ay tila sa casalan at biñagan at inaacala yata nila na ang pagcacamatay ay dapat icatoua,t, ipagcantahan, parís nang ugali ng͂ mang͂a hebreo at romano, na naniniuala na ang mg͂a namamatay ay lumulualhati. Mabuti ng͂a, na ang paghahanda at ang pagcamatay ay pagparisin nang mg͂a tagalog cung isulat para ng͂ katapúsan.

Ang patay na yao,i, ng͂ nabubuhay pa,i, Directorcillo sa bayan, at di co na sasabihin na siya,i, inaacala ng͂ lahat na marunong at matalinong isip, at ang uica pa,i, may roon dao isang biblioteca na doo,i, may isang libritong mababalaghin ña ang tauag ay sa «La

Happening to be in Paombong, Bulacan, my good friend Gatmaitan invited me to go with him to a house where we were bound to encounter dalagas [unmarried girls and adult women] and katapusan.1 I accepted the invitation and we were soon at the house of a dead man. In fact, a banquet was going on exactly like the funerary rites in the Visayas as described by Zaragoza.2 In the presence of the corpse, the men were laughing with floppy jaws wide open and directing flirty words to the girls and women from Bulacan. The Visayans, Tagalogs, and Ilocanos are similar in that their home funerary rites are just like their home weddings and baptisms; doubtless they think that deaths should be celebrated with rejoicing and singing—like the Hebrews and the Romans, who believed in the apotheosis of the dead. Thus is it fitting that the Tagalogs use the same letters for ‘banquet’ and ‘death’?

The dead man had been a directorcillo3. There is no need to say anything more, except that he regarded himself as an erudite and highly talented man, and used to say that he had a library of his own, which included a miraculous little book titled De la Compañía [Of The

1. In the original text, Isabelo explains that katapusan has two meanings: a) cheerful banquet b) the end of funerary rites, in the dead person’s home.

2. Don Miguel Zaragoza is the author of a warm ‘preface’ for El Diablo. Ambeth Ocampo tells us that the Don was a well-known painter of genres , and also the founder and editor of Ilustración Filipino. In the ‘preface’ he writes that he was thrilled when, in 1885, Isabelo dedicated to him the splendid text on the Visayas (Pintados) titled Al rededor de un cadaver, fi rst published in the newspaper titled Porvenir de Visayas.

3. During late Spanish colonial rule this was the title of a gobernadorcillo’s secretary for administrative matters in any township. In his scathing Discursos y Artículos Varios Graciano Lopez Jaena wrote that the gobernadorcillos were rich, virtually illiterate, and puppets of the secular Spanish administrators. The directorcillos were literate and puppets of the local Catholic priests. Because they handled all documents under priestly monitoring, they were actually more powerful than their titular bosses. See pages 78-96 in the new edition edited by Jaime C. Veyra (Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1951).

2. Don Miguel Zaragoza is the author of a warm ‘preface’ for El Diablo. Ambeth Ocampo tells us that the Don was a well-known painter of genres , and also the founder and editor of Ilustración Filipino. In the ‘preface’ he writes that he was thrilled when, in 1885, Isabelo dedicated to him the splendid text on the Visayas (Pintados) titled Al rededor de un cadaver, fi rst published in the newspaper titled Porvenir de Visayas.

3. During late Spanish colonial rule this was the title of a gobernadorcillo’s secretary for administrative matters in any township. In his scathing Discursos y Artículos Varios Graciano Lopez Jaena wrote that the gobernadorcillos were rich, virtually illiterate, and puppets of the secular Spanish administrators. The directorcillos were literate and puppets of the local Catholic priests. Because they handled all documents under priestly monitoring, they were actually more powerful than their titular bosses. See pages 78-96 in the new edition edited by Jaime C. Veyra (Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1951).

Compañía», ito,i, siyang nagbibigay dunong sa caniya huad cay Salomon.

Bago co pa lamang natatalos na may biblioteca ang namatay, capagcaraca,i, sinabi co cay Gatmaitan na ibig cong maquita, cayâ nga noondi,i, ipinasoc aco sa isang cuartito na nasasarhan da-hilan sa baca mauala ang nasabing librito.

Nang cami,i, nasa loob na nang cuarto, ang nabalo ay agad isinara sapagcat cang͂ ino ma,i, dî niya ipinagcacatiuala ang may cababalaghang biblioteca.

Ng͂uni,t, ang unang hinanap ng͂ caibigan cong si Gatmaitan ay ang librito, yayamang ang caniyang nais, ay mapasacaniya dî man carampatan, ang librito na anting anting.

Hindî nasumpung͂an ng͂ caibigan co, cayâ aco,i, binilungan.

---Caibigan umalis na tayo rito at baca pa paquita sa atin ang caloloua ng͂ Directorcillo. Naquita mo na ng͂a, ang librito,i, nau-alâ bagama,t, itong cuartito,i, palagui ng͂ sarado at dî binubucsan cung dî ng͂ayon lamang.

---Ja, ja, ja, naniniuala ca pala sa nang͂ag sisilabas dao na du-ende, diablo at iba pa.

---Huag cang magtaua, at ang aquing Lelang ay nagsasabing siya,i nacaquita.

---Ang Lelang naman ng͂ Nanay ay nagsasabi rin ng͂ gayon, ng͂uni,t, ¿sino ba sila? mg͂a babai lamang na ualang malay cayâ naniniuala sa caululan.

Nang maring͂ig ito ni Gatmaitan ay di napiguil ang galit at naguica...

---Marami acong masasabi sa iyong mg͂a bagay tungcol sa calo-

Company], which conferred on him all the wisdom of Solomon.4

As soon as I heard of the dead man’s library, I let Gatmaitan know my desire to see it, and at the same moment he introduced me to a little room that was still locked to avoid losing the Little Book.

But once we were inside, the widow locked the little room again, saying she did not trust anyone else to enter the mysterious library. But the first thing my friend Gatmaitan hunted for was the Little Book, because the poor fellow, believing in ancient legends, was trying to inherit, illegally, this anting-anting (amulet).

Finding nothing, my friend said to me in a low voice: “My dear friend, let’s get out of here, it could be that…the ghost of the… directorcillo will… appear before us. See how the miraculous Little Book has disappeared even though the little room has never been unlocked until today.”

I. “Ha! Ha! Ha! Do you still believe in apparitions, dwarves, demons and sorcerers?”

G. “Don’t laugh at me. My grandmother swore that she had seen some of them.”

I. “My great-grandmother said the same kind of thing to me. What are your grandmother and my great-grandmother except foolish mothers of humbug?”

On hearing my sarcasm, Gatmaitan got up from his chair, unable to hide his irritation, and replied: “I could mention to you the many cases where the souls of the dead appeared before the living, which I read about

4. At first, the editors assumed that this obscure title referred to the Jesuits, self-titled as companions of Jesus Christ. But now we know that in Ilocos Norte the ‘little book’ was a magic tool of local sprites (sangcabui). In his famous El Folk-lore Filipino Isabelo wrote that “it can take them in no time, wherever they want to go, no matter how far. All they have to do is indicate the place.” The name given to the ‘little book’ showed the reputation of Spanish Jesuits for owning miraculous books. See the English translation by Salud C. Dizon and Maria Elinora P. Imson ( Manila, University of the Philippines, 1994), page 39.

loua ng͂ mg͂a namatay na napaquita sa madlâ,na aquing nabasa sa mg͂a librong banal, datapua yayamang dito sa biblioteca ay ualang naquiquita cung di ang crónica ng͂ mg͂a nangyari dito sa Filipinas, ay babasahin co sa iyo ang isang na nangyari ng͂ taong 1690, na doon maquiquita sa talatang 342 ng͂ icaluang parte nang crónica ng͂ mg͂a Paring franciscano, at natataning naman sa ibinigay na informe ni Fr. Jose de la Virgen ayon sa cautusan ng͂ Ministro Pro-vincial nila.

Ang nangyari ay ang Franciscanong si Fr. Mateo de S. José ministro sa bayan ng͂ Buhi (Camarines) at isang sacristan ang tinauagan isang hating gabi na tinugtog ang campanilla sa pinto, upang maquita nila,i, hinahanap sila ng͂ daluang negrong naca nacapang͂ing͂ilabot taglay ay isang tagalog na principal doon (isang Capitang pasado na mayaman sa bayang yaon, na ang acala,i, na sa lang͂it dahilan sa totoong malimusin) natatanilicaan sa liig, tanda na siya,i, na pacasamâ sa Inierno.

Ipinagtatanong ng͂ Pari, lalo na sa caniyang cahambal hambal na nasapit na di man acalaing siya,i, sumagot na nagdídighay ng͂ apoy at nanang͂is na nagng͂ang͂alit, at sinabi, na sa madla niyang casalana,i, ang lalong nacapagbigay galit sa P. Dios, ay hindi la-

in religious books. But it is only in this library that one encounters the Philippine Chronicles. Let me read aloud to you a case that occurred in 1690, which can be found on page 342 of the second part of the Chronicles of the Franciscans.5 It consists of information provided by Friar José de la Virgen, following orders given by the Ministro Provincial [highest-ranking priest in that area]. What happened was that the Franciscan Friar Mateo de San José—priest in the township of Buhi in the Camarines—and his acolyte were summoned in the middle of the night by little bells ringing at the porter-gate. Th ere they encountered two ferocious black demons,6 who were dragging along an Indio [native] principal [local ‘big man’]. (He was very wealthy and had earlier been a gobernadorcillo in Buhi, which led him to believe that his glory came from his grandiose way of life and his almsgiving.) Now he was tied up with a thick chain around his throat, a sure indication of his eternal damnation. The Father asked him various questions, especially about the

5. The full original name of the book was Cronicas de la Apostólica Provincia de S. Gregorio [Magno], de Religiosos descalzos de N.S.P. San Francisco en las Islas Philipinas, China, Japon, etc.. The author, Friar Juan Francisco de San Antonio, was born in 1682 in Ripoll, near the eastern Pyrenees (amazingly, our comrade Carlos Sardiña was raised in this little township). As a youngster he witnessed the extinction of the Habsburg dynasty and its replacement by the French Bourbons. In Western Europe the secular Enlightenment was starting to ride high. It is therefore interesting that in his work he often referred to the important chroniclers of the Habsbu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Frontispiece

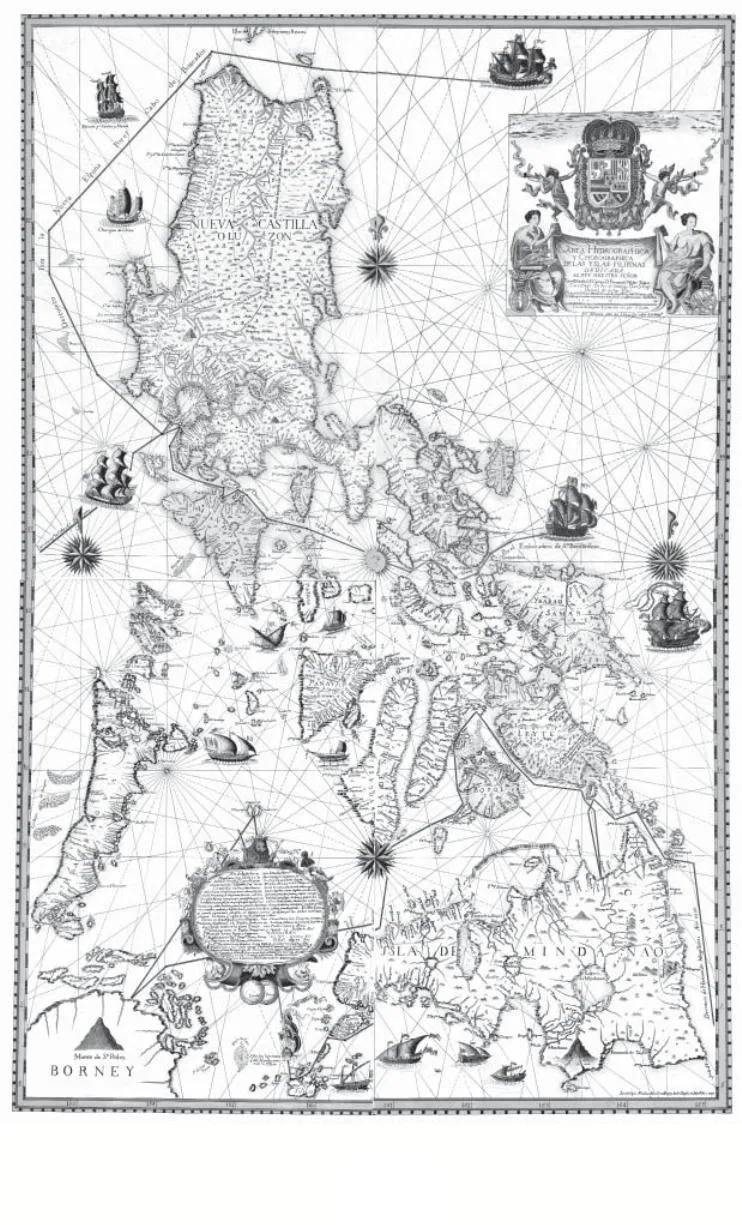

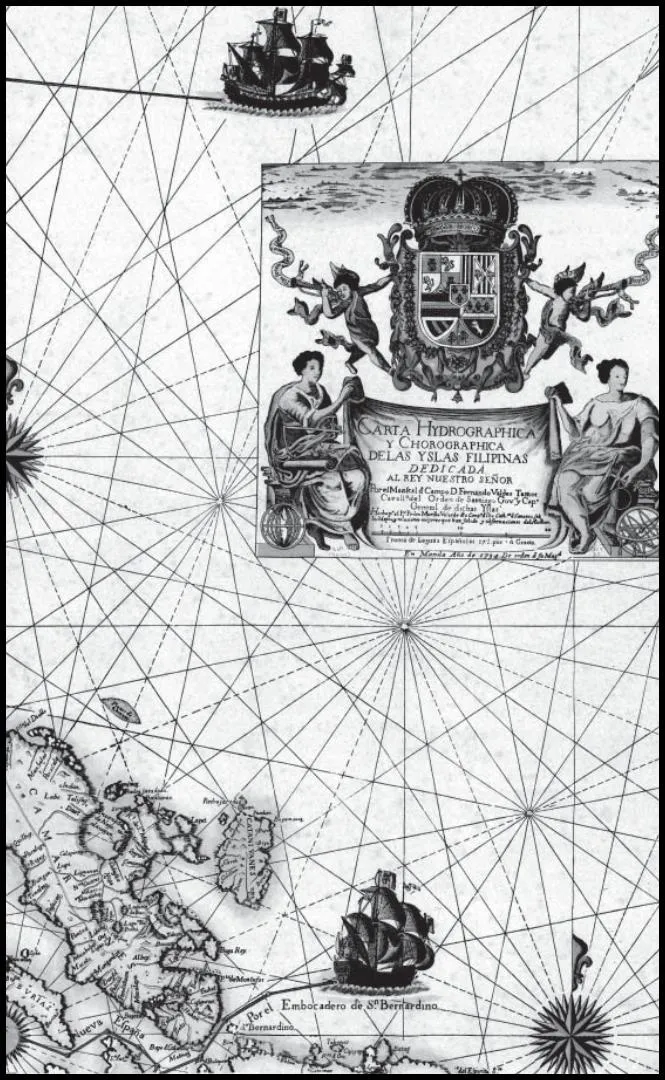

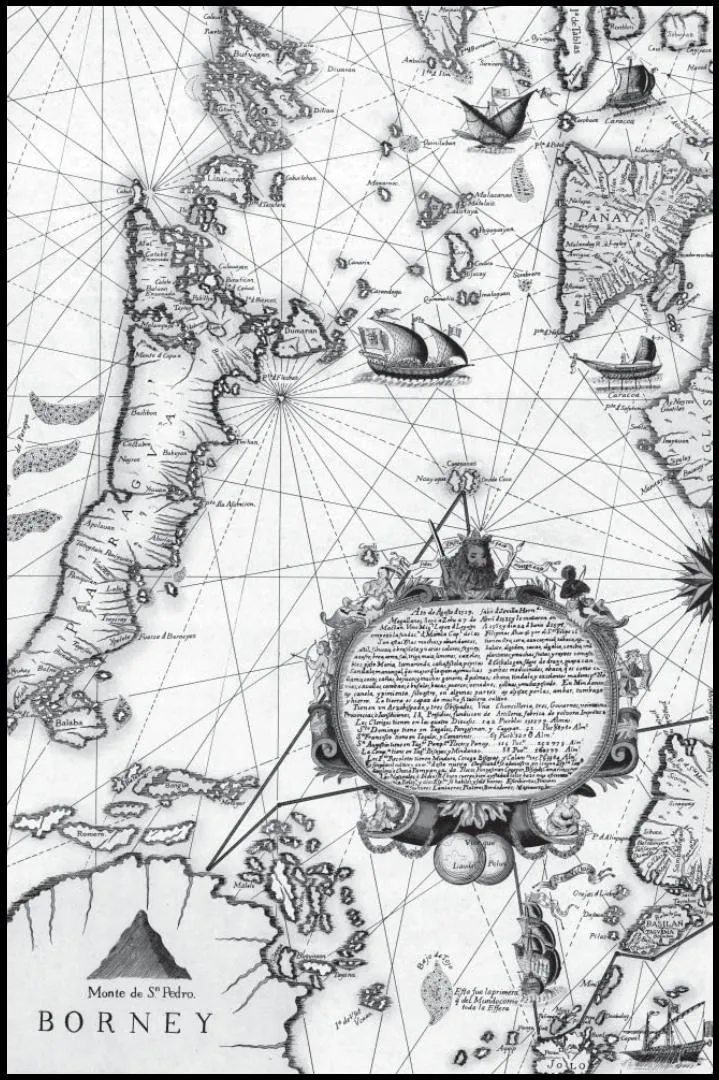

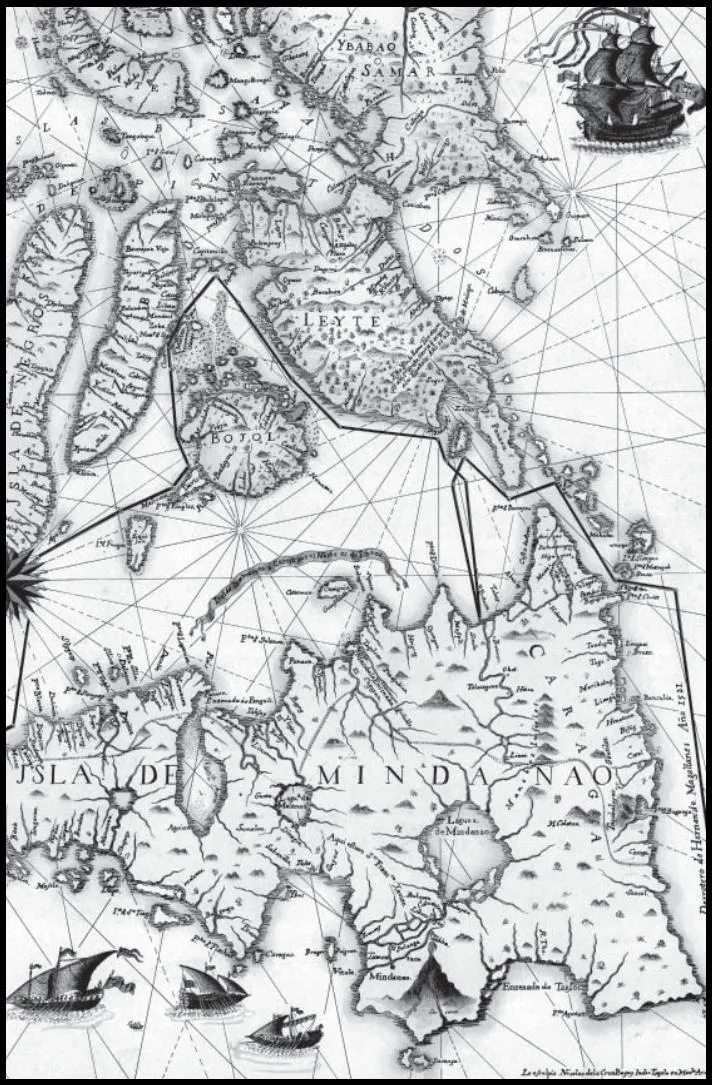

- The Murillo Velarde Map of 1734

- Introduction

- Chroniclers

- The Murillo Map Detailed Views

- Ang Diablo sa Filipinas