- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book fathoms the depths of Philippine cinema as the author ventures into the largely unknown terrain of the country's history of early cinema. With meticulous scholarship and engaging insights, prize-winning filmmaker and author Nick Deocampo investigates the origin and formation of cinema as it became the Filipinos' preeminent entertainment and cultural form.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cine by Nick Deocampo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Anvil Publishing, Inc.eBook ISBN

9786214201785Subtopic

Film & VideoChapter One

Cinema and Language

Chapter One unravels the events surrounding the arrival of cinema in the Philippines. It emphasizes the role the Spanish language played in introducing (and eventually making acceptable) the medium in the predominantly Hispanic society. Long before the actual apparatus arrived, it had been written about in Spanish newspapers. When the machine finally came, anuncios were made and reviews of screenings were written in newspapers—in Spanish. This chapter contextualizes film’s arrival within the Hispanic society that embraced its coming by baptizing it with names translated from French (chronophotographe became cronofotógrafo or cinematographe became cinematógrafo.) Everything associated with the film apparatus was named in Spanish, including material properties like the screen called telon. French or American titles were translated into Spanish (Lumiere’s La danse egyptienne became La danza egipciana / The Egyptian Dance.) Intertitles and subtitles were likewise flashed on screen in Spanish (accompanied by English and even Tagalog translations.) Announcements, reviews and criticisms were written in the dominant Castilian language. It was a Hispanic world.

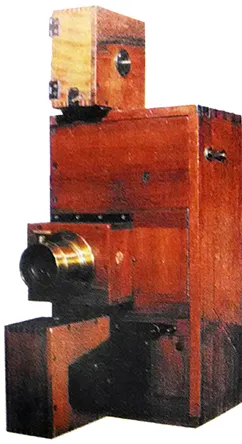

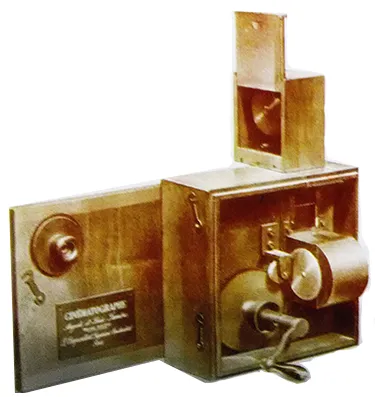

Aside from language, Chapter One also deals with cinema as technology. The beginnings of cinema in the Philippines is veiled in mystery. What was the first cinematographic machine? Was it truly a film device? Agustin Sotto for example, alleges that the cronofotógrafo was a stereopticon, which offered merely “a slideshow presentation.” The chapter reviews the technological history of the various apparatuses, particularly the cronofotógrafo. Only by understanding the technical history of the moving picture machine can one have a clearer idea about the forms of cinema that first came into the country.

Finally, this chapter offers a glimpse of the initial contact cinema made locally. It introduces pioneer entrepreneurs like the Spaniards Señor Francisco Pertierra and Antonio Ramos, as well as the Swiss businessmen Leibman and Peritz. They were responsible for inaugurating film in the country. Reviews of the film screenings are noted and early film practices of advertising and scheduling film programs are discussed.

The Spanish Language as Homogenizing Force

The three centuries and a half of Spanish presence in the Philippines influenced all aspects of native life. It left its indelible mark in arts and culture by bringing in new forms as well as enriching old ones.

The case of cinema, however, at first blush, seems different. We do not as readily see it as a Spanish legacy as we do, say, Catholicism. Cinema, after all, was not any more indigenous to Spain as it was to the Philippines. In fact, Spain was ahead of its colony by only eight months. The first film screening in Spain happened on May 15, 1896.1 In the Philippines it happened on January 1, 1897. Cinema in the Philippines flourished only when the Philippines had become a colony of America, whose subsequent global domination of the industry greatly enhanced the Philippines’ access to film.

How, then, does one consider the Spanish influences in the cinema that grew in the Philippines? Where must one seek for traces of Spanish-ness in Filipino film? How does one account for such influences? How were they absorbed and perpetuated? In what way did Spanish influences become indigenized? In the process of indigenization, how was local culture transformed? How were Spanish influences inscribed in cinema even as the medium fell into the hands of the Americans? How were Spanish influences adapted into the creation of a “national cinema”?

These questions have been largely ignored by previous film historians for various reasons not altogether invalid. The distance in time between subject and scholar is a major obstacle. The language used then, Spanish, is another, as it is no longer the lingua franca of present-day Filipinos. Much of the knowledge and understanding of cinema during the Spanish regime—all written in Spanish—have escaped many contemporary scholars. Infant cinema in the Philippines was also swaddled in a technology that by today’s norms would be crude, primitive, and even incomprehensible. Moreover, early cinema was distributed, sold, promoted, and exhibited in a different way. Likewise, the audiences watched and thought about cinema differently froth the way Filipinos today. In the late nineteenth century, they watched films whose conventions of dramaturgy and spectacle are now foreign to the present generation. Despite all these obstacles, however, studying the Spanish influences on early cinema in the Philippines allows one to arrive at a genesis of how a foreign medium like cinema became the country’s most dominant cultural expression in the twentieth century.

We begin with language. Long before the arrival of the film apparatus in the country, its name was already being heralded in newspapers: cinematógrafo. The name was the Spanish equivalent of the French cinematographe. Knowledge of cinema preceded its physical presence. It was facilitated by the written word—in Spanish. Newspaper accounts announced its impending arrival, although nobody in the archipelago had ever seen it before.

This much-anticipated machine, however, failed to materialize. Ernie de Pedro writes, “Manila newspapers report that since October 1896, a Spanish businessman had been trying to import a Lumiere Cinematographe from Paris, but the waiting time was too long.”2 It was another motion picture device, imported by another Spanish businessman, Señor Francisco Pertierra, which would make possible the screening of the first motion picture in the country. The anuncios called it cronofotógrafo.

This is how the 1896 model of the Demeny-Gaumont chronophotographe looks like, possibly the same model used by Señor Pertierra in pioneering the country’s film screenings.

Replica of the Lumiere cinematographe

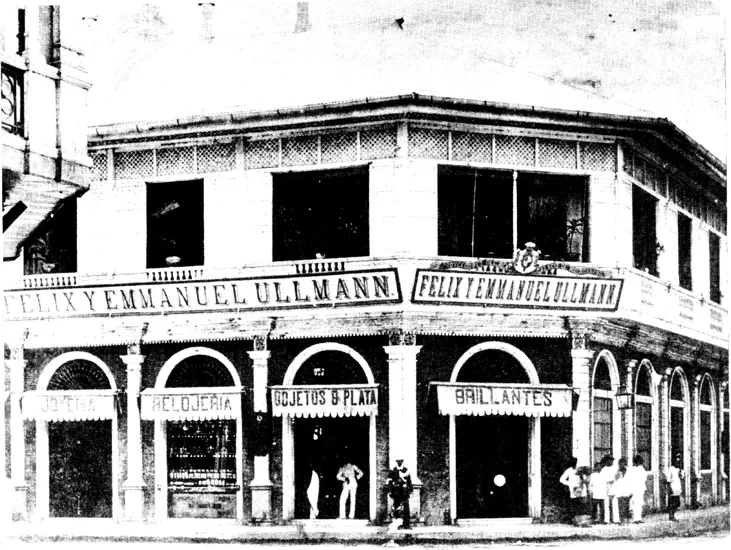

“En el local de la Escolta, esquina de la calle de San Jacinto, donde hace tiempo estaba la joyeria de los Sres. Ullmann, los Sres. Leibman y Peritz han instalado un aparato cinematógrafo, que anoche se exhibio por primera vez al publico, y anteanoche hizo pruebas ante reducido numero de invitados.”

-El Comercio, Agosto 30, 1897

“Along the Escolta corner San Jacinto street where the jewelry shop of Messrs. Ullman used to be, Messrs. Leibman and Peritz have installed a cinematograph which last night showed films to the public for the first time, and to a select number of guests the night before.”

-El Comercio, August 30, 1897

As it was with the cinematógrafo, the name given in the Philippines for the machine was not the same as that given by its inventor. The French who had invented it named it chronophotographe. But the Philippines newspapers called it by its Spanish equivalent: cronofotógrafo. And quite naturally! For who would dare use a French term when the Philippines was a Spanish colony?

Peep show devices allowed one viewer to drop a coin and view a looped film show.

The first act of cinema’s assimilation thus began. Through naming and translation, cinema was born in the Philippines. While the material device was yet absent in the islands, there was already a word for it—in Spanish. People could identify it. They had something to call it by. They began to know about it. It was only a matter of time before the word would become the machine. The delay only added to the suspense. The wait was like a gestation period, a kind of incubation, or a period before the arrival of a child. When finally the machine came, the word was fulfilled.

The role the Spanish language played in introducing the foreign object to Filipinos foreshadows the role that language would take in making Filipinos accept cinema as their own. Consider this: when the cronofotógrafo was later dislodged by the cinematógrafo, the word cinematógrafo was eventually shortened to cine to refer to the movie house. This was later adapted as the Tagalog sine, referring not only to the movie theater but also to the movie itself, as in “Manood tayo ng sine!” (Let’s watch a movie!) The use of Spanish homogenized the understanding of early cinema. In a manner of speaking, Spanish named and thereby “realized” cinema.

It must be noted that film was not only a new invention but also an international one. Film came from France, Germany, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, and USA. The films brought to the country did not necessarily come from Spain but from those countries. (Cinema as a system involving production, exhibition, and distribution was as underdeveloped in Spain as it...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgement

- Introduction

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Photo