![]()

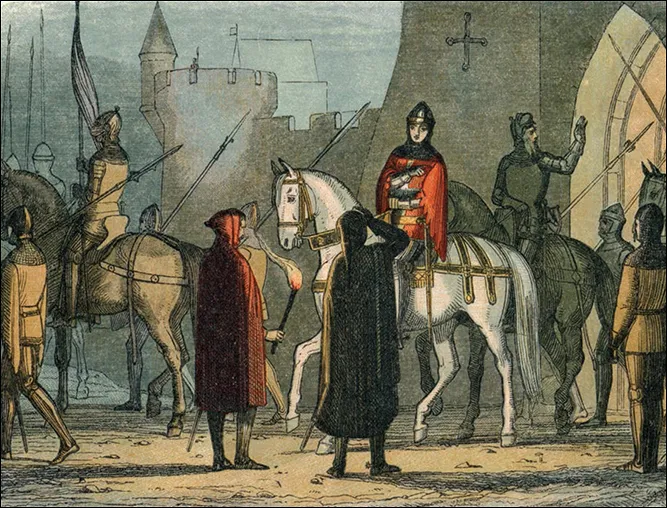

The great English victory won by Henry V at Agincourt in 1415 may have prompted the French king Charles VI into a fit of madness; a trait passed on to his descendants. The coronation of Henry V (above) was held at Westminster Abbey in 1413.

1

THE WARS OF THE ROSES

FOUNDATIONS OF

THE WARS OF THE ROSES

At the time of Henry V’s coronation in 1413, France was weak, creating a good opportunity for Henry to press his claim to the French crown as a descendant of Edward III. Resistance to an invasion was likely to be slow in developing, disorganized and perhaps half-hearted.

——♦——

‘He became known for a time as Charles the Beloved’.

The French king was unpopular, the kingdom was financially embarrassed and it was even possible that some French nobles would accept or at least not oppose an English bid for the throne.

The French king, Charles VI, had taken the throne in 1380 at the age of 11. He could not legally wield power at this age so four of his uncles – all of course great nobles in their own right, and with agendas of their own – were to govern the country until Charles came of age at 14. In the event it was actually several more years before Charles was able to assert himself, and by this time his regents had created several serious problems.

Charles’ four uncles put their own interests foremost, spending royal money on projects of their own or to block the manoeuvres of the others. Increased taxation to pay for all this infighting created unrest and even revolts, until finally Charles took power in his own right and began to restore matters. He was sufficiently successful that he became known for a time as Charles the Beloved, largely as a result of a brief period of prosperity created by his policies.

Mental illness ran in the family of Charles the Beloved, and in 1392 it manifested itself for the first time. Whilst on the way to Brittany, Charles suddenly lapsed into violent insanity and killed members of his own escort before he could be restrained. Further episodes followed, in which he would attack anyone nearby or flee in terror from unseen assailants. Between bouts of insanity he was rational, but not capable of good governance. This led to a new set of power-struggles in France, which gradually became a civil war between the Duke of Burgundy and a faction named for Bernard, Duke of Armagnac.

With France in such turmoil, Henry V considered he had an excellent opportunity to make territorial gains. His plans were initially opposed by Parliament, which preferred negotiation, but by early 1415 Parliament had agreed to sanction war with France.

In 1392, Charles VI of France suddenly turned on his escort and attacked them. His subsequent bouts of insanity gained him the nickname ‘Charles the Mad’. This tendency to madness was passed to his descendants including Henry VI of England.

Plots against Henry

Although he eventually obtained the reluctant support of Parliament for his invasion of France, Henry faced internal troubles that had to be dealt with before he could launch a foreign expedition. He had been generally successful in building support among the nobility of England, restoring the estates and titles of those who had lost them during his father’s reign. His first two years on the throne were not without their troubles, however.

‘Whilst on the way to Brittany, Charles suddenly lapsed into violent insanity and killed members of his own escort before he could be restrained’.

A Lollard plot to capture Henry V failed when the king was warned of the danger. Despite claims that they had a hundred thousand men, only around three hundred Lollard supporters arrived at London. These were easily captured by royal forces.

One challenge came from the religious movement known as the Lollards, who were opposed to various features of the Catholic Church. The Lollards believed religion to be very much a personal matter, with Scripture accessible to all who could read it in English. They also were at odds with the idea of a politically powerful and wealthy Church, believing that religion should be separated from politics. These dangerous ideas ran contrary to the accepted order of things, although some powerful noblemen supported the movement.

Henry Bolingbroke had a blood claim to the throne as a son of John of Gaunt. However, his bid to take it was successful more due to Richard II’s increasing unpopularity than the legality of Henry’s claim.

Among these was John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and grandfather of Henry V of England. Other noblemen embraced the concepts of Lollardy but tended to be discreet about their support for what was at times considered heresy. The Lollard movement was seen as a serious threat to the existing social structure; sufficiently so that John of Gaunt’s son, Henry IV, passed laws that prohibited some aspects of Lollard practice such as translating the Bible into English, and also authorized the practice of punishing heresy by burning at the stake, which was continued into Henry V’s reign. Indeed, just before his coronation in 1413, his friend John Oldcastle was accused of heresy as a member of the Lollard movement. Henry V tried to persuade Oldcastle to relent of his heretical beliefs, but he would not do so.

This placed Henry in a difficult position. He did not want to act against his friend, but Lollardy was a serious threat to stability in his kingdom and Henry needed the support of the Church as well as the great nobility. He permitted proceedings against Oldcastle to go ahead, but granted him a reprieve whilst he tried further persuasion. These half-measures worked against Henry. Oldcastle escaped from the Tower of London and led a Lollard insurrection against the crown. His plan was to kidnap King Henry and set himself up as Regent, which would allow religious and social reforms to be pushed through. Henry was warned of the plot, which came to nothing, but Oldcastle continued to be a nuisance until 1417. He was involved in various plots during the next few years, including the Southampton Plot. Most of these intrigues achieved little, and eventually Oldcastle was captured. He was put to death in 1417, though sources vary on whether he was burned as a heretic or was hanged and then burned. Either way, Henry V was forced to have his old friend put to death in a horrible manner for the sake of stability in his kingdom.

Edmund Mortimer’s Claim

A more persistent problem was the claim of Edmund Mortimer to the English throne. Mortimer was Earl of March, and descended from the second son of Edward III. This gave him a better claim than Henry V, who was descended from Edward’s third son. Mortimer and his father had also been heirs presumptive to Richard II. Essentially this meant that unless Richard produced a son who would be his heir, the Mortimers would inherit the throne of England. That changed when Richard II was deposed by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke (Henry IV).

‘Oldcastle was captured. He was put to death in 1417, though sources vary on whether he was burned as a heretic or was hanged then burned.’

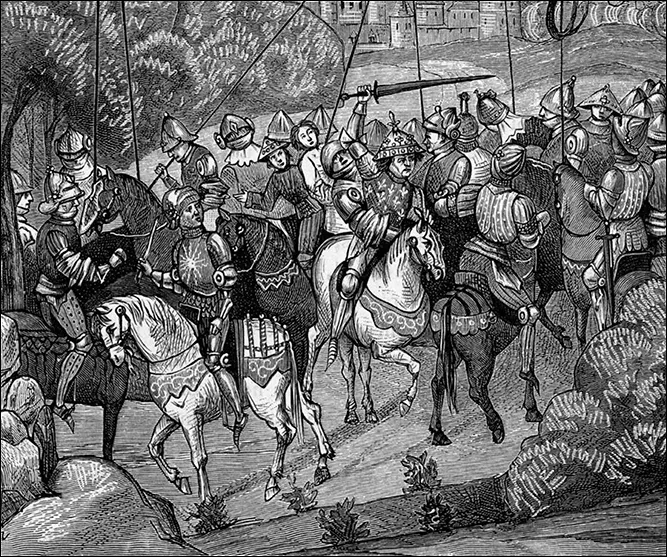

In 1403 the powerful Percy family, Earls of Northumberland, had revolted and attempted to overthrow Henry IV. Their bid was unsuccessful, with some of the ringleaders captured and sentenced to death by hanging, drawing and quartering. The Earl of Northumberland managed to escape to Scotland and raise another force. A second attempt in 1405 was also defeated. This time the rebel leaders were tried under irregular circumstances before being sentenced to death by beheading. A third rising in 1408 was also soundly defeated. Instrumental in putting down these rebellions was the young man who would become Henry V.

At the time of the 1403–8 rebellions, rumours persisted that Richard II was still alive, perhaps in exile at the court of Scotland. A successful uprising could put him back on the throne in place of Henry IV who had deposed him. Alternatively, Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, was an excellent candidate to replace Henry. The risings failed, of course, but the intrigues continued after Henry IV died and his son Henry V took the throne.

‘The intent was to kill Henry and his brothers at Southampton whilst final preparations were being made to invade France’.

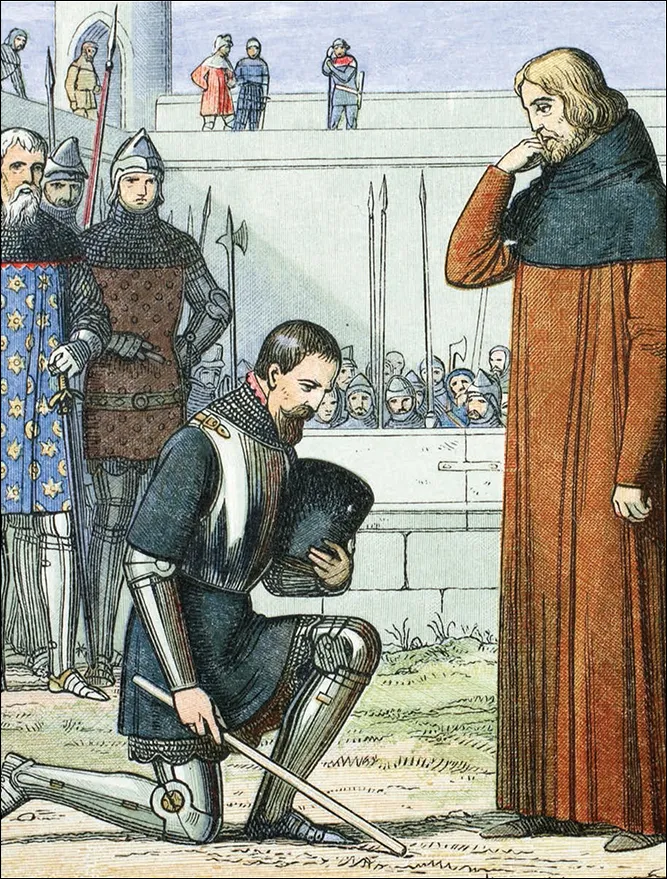

Edmund Mortimer and his brother Roger had spent several years under close supervision during the reign of Henry IV, with the young Henry V as his guardian for much of this time. Edmund and Henry were of similar ages, and despite whatever resentment Edmund might have harboured about no longer being heir to the throne, he became a loyal supporter of Henry. As one of his first acts as king, Henry V freed the Mortimer brothers and inducted them into the Order of the Bath. Mortimer was among those who attended the Parliament in 1415 that agreed to war against France, and subsequently took part in Henry’s campaign. In the meantime, he became aware of a conspiracy that had developed.

Known variously as the Cambridge Plot or the Southampton Plot, the plan was led by the Earl of Cambridge. The intent was to kill Henry and his brothers at Southampton whilst final preparations were being made to invade France, and to install Mortimer as king. However, Mortimer revealed the plot to Henry and the leaders were arrested. Mortimer took part in the investigation that condemned the Earl of Cambridge – Mortimer’s brother-in-law – to death.

Mortimer subsequently accompanied Henry to France but returned after contracting dysentery at the siege of Harfleur. He rejoined later campaigns and played a prominent role in the coronation of Henry’s French bride, Catherine of Valois. His strong blood claim to the throne could have made him or his descendants a threat had another plot formed around the family, but Mortimer died without issue. Upon his death in 1425 his estate and titles passed to Richard, Duke of York.

Henry’s Campaigns in France

Whilst the Southampton Plot was unfolding, Henry V raised an army for his invasion of France. His force landed during August 1415, marching quickly to besiege the port of Harfleur. The siege was made famous by Shakespeare’s play, and was undertaken to secure a line of communication back to England. Possession of a port would allow supplies and reinforcements to be brought in without undue difficulty, and until this was assured Henry’s army was in a difficult position without the prospect of resupply or retreat if seriously threatened.

The siege followed a fairly conventional pattern for the era. After surrounding the city to cut it off, the English set up a battery of cannon, covered by archers, and created breaches in the walls. The defenders offered an accommodation whereby the city would be surrendered if not relieved by 23 September. No French army had arrived during the month-long siege, other than some local reinforcements rushed in as soon as the English arrived, so Harfleur duly surrendered. Although he had captured his first objective, Henry was not in a good position. An outbreak of dysentery among his troops, added to casualties from the siege, reduced his army to the point where he could not effectively continue the campaign. A withdrawal to England was not acceptable as it would make the campaign look like a failure, so Henry resolved to march to Calais.

Edmund Mortimer was a potential threat to Henry IV, and thus was arrested and closely watched. He became a good friend and supporter of his captor, the young Henry V, and was released as soon as Henry V became king.

Henry’s plan was to undertake a variant on the well-established tactic of the chevauchée. As the name suggests, this was normally a fast-moving mounted raid, but Henry intended to accomplish much the same level of destruction by marching an army mostly composed of footsoldiers through enemy territory. His army would destroy whatever his men could not carry off, weakening the French economically as well as poli...