![]()

Showdown in

Tennessee

by Carol Lynn Yellin

t 5 p.m. on June 4, 1919, when the Sixty-sixth Congress yielded up the two-thirds majority required for passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, a victory celebration among American woman suffragists seemed in order. After all, 21 successive Congresses had previously rejected this federal Suffrage Amendment, and it had taken over 70 years of petitioning, lobbying, politicking, and, most recently, picketing by four generations of right-to-vote crusaders to bring the struggle for enfranchisement of women to this high ground.

But the battle-weary, campaign-wise suffrage forces did not celebrate. In the headquarters of Carrie Chapman Catt’s National American Woman Suffrage Association at 171 Madison Avenue, New York, the joy was restrained. The NAWSA women remembered how often their brave labors to win full suffrage state by state through amendments to state constitutions had met with heartbreak; they remembered how regularly their stubborn skirmishes to win the half-a-loaf of partial suffrage (voting only in presidential or municipal elections that was sometimes possible through state legislative enactment) had ended in disappointment; they remembered how all of this had led inevitably to the concerted push for federal amendment action. Remembering, they knew that total victory had not yet been won.

In the headquarters of the National Woman’s Party just off Lafayette Park in Washington on that June night, there was business as usual among Alice Paul’s select, young, banner-bearing color guards. They remembered how their silent and dramatic pro-amendment demonstrations in the halls of Congress and at the gates of the White House had outraged, then intrigued, and finally touched the conscience of the American public; they remembered how this had helped overcome the last bastions of congressional resistance. And yet they knew they could not pause to celebrate.

For the long-fought-for passage of the 19th Amendment by Congress in June, 1919, meant only the capture of a beachhead. The final campaign in this nation’s longest and most civil “war,” the campaign for ratification of the 19th Amendment, still lay ahead. And up the 48 hills once more, all the way — that battle must be won in the states. State by state. To complete adoption of the amendment now being submitted by Congress to the 48 states required ratification by legislatures in three-fourths of those states.

The Suffs, as headline writers liked to call them, had to win in no fewer than 36 legislatures, while their opponents, the entrenched and well-heeled Antis, could kill the amendment by squashing it in just 13 legislatures. And behind the Antis’ formally organized battalions — a National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (for ladies) and the American Constitutional League (for gentlemen) — stood the suffragists’ real and most powerful enemies, a shadowy conglomerate of special interests referred to by the suffragists as the whiskey ring, the railroad trust, and the manufacturers’ lobby. Suffragist historian Ida Husted Harper once explained the how and why of their sinister manipulations:

The hand of the great moneyed corporations is on the lever of the party ’machines.’ They can calculate to a nicety how many voters must be bought, how many candidates must be ’fixed,’ how many officials must be owned. The entrance of woman in the field would upset all calculations, add to the expenses if she were corruptible, and spoil the plans if she were not.

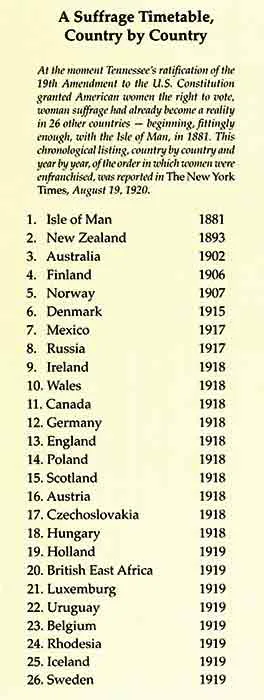

Although no time limit for completion of ratification had been written into the 19th Amendment (cynics were already predicting it would take 20 years), there was no time to lose if women’s votes were to count in the upcoming 1920 elections, a matter, as the Suffs often proclaimed, of patriotic pride no less than simple justice. In a world we had helped make so safe for democracy, democratic Americans could not lag behind. Women already voted in 26 other nations. (Including Germany! Including Russia!!) More than that, the memory of American women’s contributions to Allied victory in World War I — their crucial work on farms and in offices, hospitals, and munitions factories was rapidly fading, and with the country longing to return to what would soon be labeled “normalcy,” suffrage forces knew that, psychologically, it was action now or never.

Thus it was that at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, June 4, 1919, just one hour after the decisive U.S. Senate vote on the 19th Amendment, the redoubtable, twice-widowed 60-year-old Carrie Chapman Catt, heiress to the mantle of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, veteran of more than 30 years in the suffrage movement and leader of its 2,000,000-member “traditional” wing, was hard at work in her office at NAWSA headquarters. She was methodically sending out telegrams to governors of all states where legislatures had already adjourned in that off-year of 1919, urging them to call special sessions to act on ratification as soon as possible. By midnight, the serenely efficient Mrs. Catt also had dispatched messages to each of the 48 state suffrage auxiliaries, exhorting them to put their long-planned ratification campaigns into high gear and reminding them, where necessary, to keep after their governors. Only when all of her own telegrams had gone out did Mrs. Catt read the congratulatory messages pouring in, among them a two-word cable from President Woodrow Wilson, in France for the Paris Peace Commission: “Glory Hallelujah!”

Alice Paul, too, was pushing on with single-minded intensity that Wednesday night. But the quiet, dedicated, 35-year-old Quaker social worker, who had gone to prison as an activist convert to the votes-for-women cause in England a decade earlier and now was leader of an estimated 25,000 women in the “militant” wing of the American movement, was not to be found in her office. She had boarded a train and was heading west to join her fieldworkers in a whirlwind tour of the several states where legislatures were still in session and where, beginning early the next morning, suffragists would be demanding immediate ratification.

In years gone by, Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul had been contending rivals for the allegiance of American suffragists. The groups they led — the sprawling, well-established, persevering NAWSA, and the smaller, more maneuverable, less predictable Woman’s Party — had only recently been bitterly divided over tactics, particularly over the effectiveness of White House picketing to “educate” an initially reluctant President Wilson on the need for a federal Suffrage Amendment and the responsibility of party leadership to achieve it. Now, however, their strategies meshing by unpremeditated design, the rivals seemed to be taking this last giant step for womankind together.

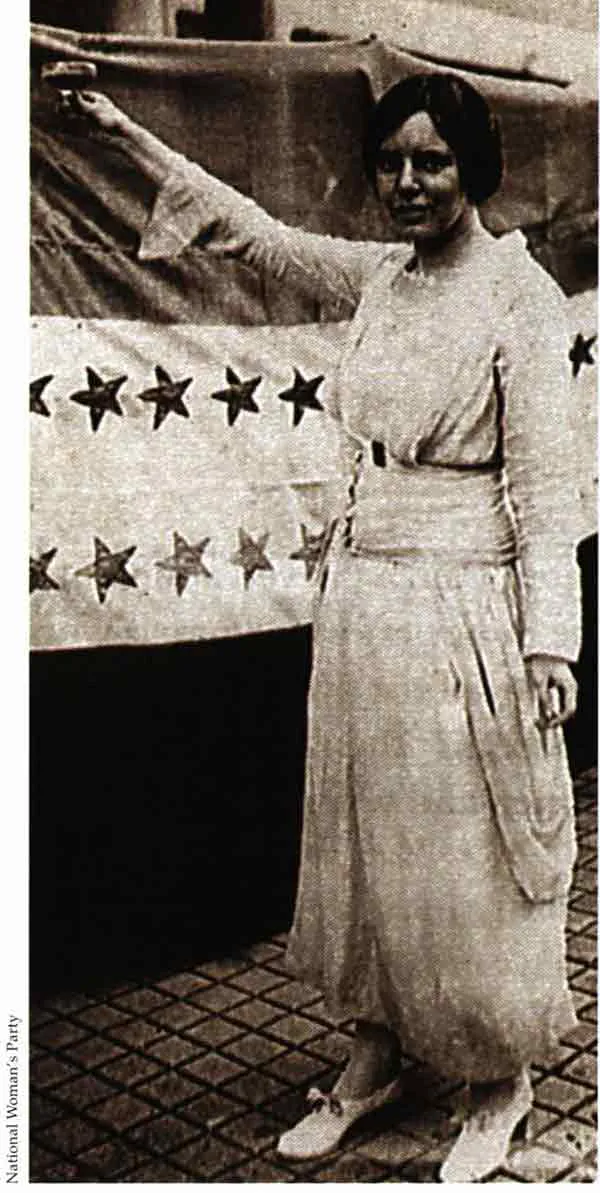

Alice Paul toasting suffrage victory.

It augured well for the climactic struggle ahead.

The first six ratifications came in an eight-day period: Wisconsin, Michigan, Kansas, Ohio, New York, Illinois. Letter-writing and lobbying, speechmaking and fund-raising intensified. In the next seven weeks, another seven states ratified. As summer wore on, still the Suffs campaigned — staging rallies, conducting polls, issuing press releases. The Antis mobilized in kind. A corps of impassioned lady orators, headed by a woman attorney named Charlotte Rowe from Yonkers, New York, charged to state capitals to warn the populace in general and legislators in particular that ratification was the first step toward socialism, free love, and the breakup of the American family. One Southern governor, Ruffin G. Pleasant of Louisiana, publicly sought a union of 13 Anti states to prevent ratification.

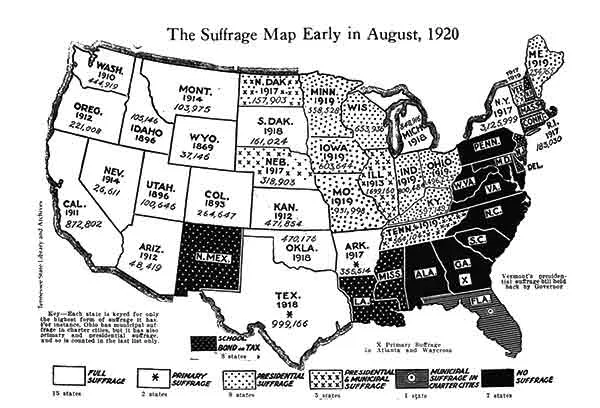

By mid-September, the pace of ratification had slackened. The suffragists were particularly distressed by the failure of Far Western states, whose own female citizens had long enjoyed full suffrage, to come to the aid of voteless women elsewhere. Of these, only Montana had ratified. So the Suffs, as was their habit when coping with disappointment, redoubled their efforts — more meetings with party leaders, more pleas for special sessions, more volunteers out rounding up pledges of support among more thousands of legislators.

By New Year’s Day, 1920, the total had reached 22 hard-won ratifications. Then, in late January and early February, there came a bouquet of 10 more ratifications, clustered as if to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Susan B. Anthony on February 15. (It was Susan B. Anthony, most venerated and undeviating of suffrage leaders, who had put on paper the exact words of the federal Suffrage Amendment when it was first introduced in the Forty-fifth Congress in 1878 and then had watched its regular defeat in each session thereafter until her death in 1906 — murmuring, according to suffragist mythology,” Failure is impossible!”) Only four more states to go! Yet it was still too soon to celebrate. Or relax.

The opposition was growing ever grimmer, the odds longer, the gains more costly. In Oklahoma, Miss Aloysius Larch-Miller, a prominent and gifted young suffragist, ill with influenza, disregarded her doctor’s orders and left her sickbed to debate the state’s leading anti-suffrage politician at a state Democratic convention. Two days later she was dead. But her eloquence (plus her sacrifice) had won some decisive switchover votes in the Democratic-controlled state legislature. On February 27, Oklahoma became the 33rd state to ratify.

Meanwhile, once-promising West Virginia was now hopelessly deadlocked. Restive Antis demanded that the legislature close up shop and go home. But an absent pro-suffrage legislator, Senator Jesse A. Bloch, rushed back home by special train from California — five days across the continent while his embattled colleagues fought adjournment and the country watched and waited — to break a tie vote in the state Senate on March 20 and make West Virginia the 34th ratifying state. On March 22, news was flashed across the country that the legislature of the state of Washington, called into special session at long last by a dilatory governor, had unanimously completed ratification number 35. Where was number 36?

It was just here, with final victory so amazingly and tantalizingly close, that the ratification campaign stalled.

Six states, all Southern, had already rejected the amendment. Only seven states had not yet acted, and three of these Florida, Louisiana, and North Carolina were also from the Deep and Democratic South. No chance there, where memories of federally-controlled elections during the dark days of Reconstruction still rankled, and the 19th Amendment, with its Section 2 granting enforcement powers to Congress, was anathema. (Shades of the oppressive Fourteenth Amendment! And worse yet, the Fifteenth giving the vote to Negroes! Well, Negro men, at any rate!)

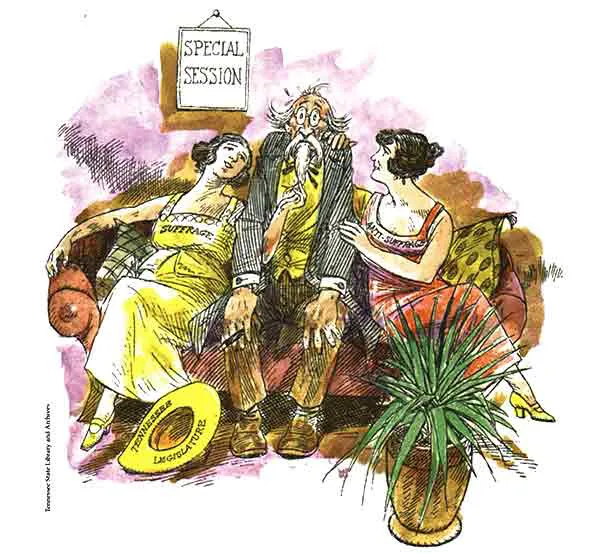

Nor was there much hope up in New England in the two rock-ribbed Republican holdout states of Connecticut and Vermont. Both had strong anti-suffrage governors who had proven granite-like in their refusal even to consider calling their reportedly pro-suffrage legislators into special session. This meant that the Suffs would have to find their “Perfect 36,” as cartoonists had labeled the elusive thirty-sixth ratification, in one of just two states, Delaware or Tennessee. And the border state of Tennessee was decidedly a question mark.

Incumbent Tennessee legislators, in the session just adjourned, somewhat surprisingly had granted women voters partial suffrage in presidential and municipal elections, the first of the old Confederacy states to do so. But full, federally-imposed woman suffrage was a mare of a different color. In any case, Tennessee was hemmed in by a provision in its own state constitution requiring that any federal amendment be acted upon only by a legislature that “shall have been elected after such amendment is submitted.” This clearly meant after the 1920 elections. For this reason, Tennessee’s Democratic Governor Albert H. Roberts (whose own suffrage sentiments were still unclear) claimed he could not call a special session of the current Tennessee legislature to act on ratification.

Which left only Delaware. In 1787, Delaware had been the first state to ratify the Constitution itself, and for a time that spring of 1920, it promised to be the last and deciding state to ratify the Constitution’s 19th Amendment. Delaware’s fervently pro-suffrage Republican Governor John G. Townsend had called the Republican-controlled legislature into special session on March 22, the very day of the 35th ratification out in Washington. Since comfortable Republican majorities in both legislative houses had long since pledged their votes for ratification, suffragists confidently expected instant action. But Delaware Republicans were in the midst of a fierce party feud. An almost equal division between pro-Townsend and anti-Townsend factions ensured that whatever the governor favored, his political rivals would oppose. In such circumstances pledges were forgotten and, amidst charges of vote-swapping, bribe-taking, and double-cross, the possibility of achieving stable pro-ratification majorities in both houses of the legislature slipped away. Weeks dragged by. March turned to April, April to May. The legislature remained in session, but no action was taken. Chances for victory in Republican Delaware receded with each passing day.

Then, most ominous of all, came the danger that some of the already-certified ratifications might be “recalled.” In Ohio, one of the first states to act favorably on the amendment, petitions had been filed for a statewide referendum in which voters could confirm or reject their legislature’s ratification. A recently- adopted article in Ohio’s own state constitution specifically allowed such a referendum. The U.S. Constitution, on the other hand, with its straightforward requirement for amendment ratification by state legislatures, is equally specific in not providing for a recall referendum. So the validity of the Ohio referendum provision was being contested in an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. But the Antis, reveling in the legal havoc being created, were busily circulating petitions for similar post-ratification referendums in Missouri, Nebraska, Maine, and Massachusetts, with more to come. The ratification campaign had not just stalled. It was threatening to shift into reverse.

June 2, 1920, was the day of decision in Delaware’s legislature. Ratification lost. Worried Republicans wondered if their party would be blamed nationally for the debacle. They didn’t have long to wonder. The following week, when the Republican National Convention of 1920 opened in the Coliseum in Chicago — a convention from whose “smoke-filled rooms” Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio would emerge as nominee for president — a long line of women, dressed in white and wearing the suffragists’ emblematic yellow sashes, marched on the Coliseum. They carried the purple, white, and gold tri-color of the Woman’s Party, and the...