- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Twenty years after The Boys from the Barracks —chronicling the attempted coups in the 1980s—Criselda Yabes returned to the military in the field of Muslim Mindanao, where the struggle to find peace is taking place to end one of the country's longest-running insurgencies. Says writer Patricio Abinales: "(This book) is, as far as I know, the first intimate look at everyday life inside military camps. Yabes has given us portrait after portrait of soldiers and officers who fight the country's internal wars—in all their nobility and their flaws."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Peace Warriors by Criselda Yabes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Nationale Sicherheit. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Anvil Publishing, Inc.eBook ISBN

9786214201389

The two Huey choppers look forlorn in the field of grass, lonely fixtures in a temporary setting. But they are captivating, not in their old, functional form, but because of the idea that you can soar with them in the sky. I must try to be in one of them. I must fly out of here. I have come this early in the morning to push my luck, which has not been working in my favor since yesterday when I arrived here in Zamboanga, the gateway to the southern chain of islands of the Sulu Archipelago. The commercial Seair flight is fully booked, and not even my man on the ground could do anything about it. The Weesam ferry is on dry dock for repairs. I rarely plan these trips in advance; the wind is my guide. I go on the spur of the moment, a nudge, an instinct or an invitation.

The Huey is my best chance.

The 206th Tactical Helicopter Squadron does not like the idea of putting me on the ride, and if they happen to change their minds, I have to sign a waiver; they don’t want to take responsibility for a journalist. That’s understandable because many of the aircraft such as these Hueys are so outdated, their use stretched way past their life spans—from as far back as the Vietnam War era, and so there have been accidents. Yet in the past I drew immense joy from these chopper rides on news assignments. They were the highlight of covering the military, they took you to places where judgment of a country ceased, where the flight itself was transcendence. So whatever they ask of me now as a precondition to being on the Huey’s manifest is a minor inconvenience, a concession I am more than willing to give. But the excitement I once had has been replaced by paranoia.

This is unprecedented, wrongfully overtaking my spirit of adventure, crushing my morale, which I could only blame on hormones going out of whack, the natural physiological consequence following major surgery undertaken a few months back has pushed my body to a heightened state of emotion. Worst of all, I cannot even carry my backpack.

There is only one solution and I cannot balk: get on that chopper.

An officer comes walking towards me and I brace myself. This is it: he’s about to decide on my fate, and God help him if I break down in tears or go on a rampage. But instead, he very politely asks my name, writes down each letter as I spell it, totally erasing all my expectations of a confrontation. He jots it down on a corner space of a page of an old magazine that he might likely throw in a pile of trash afterwards. There is no waiver requested, none of that official rigmarole.

I am the only passenger. The crew of four is wearing tee shirts that say, with great confidence, ‘We Don’t Fly/We Force The Air Into Submission.’ To steady myself, I focus on the pilot’s back, his nape is clean and smooth from the razor’s neat shave of his short black hair. Did his wife have the time to pamper him before this mission; or, being an officer, did he merely fall into a routine of regular grooming when a barber made the round of the quarters?

One of the copilots helps me onto the back seat; and when he straps the seat belt around my lap, I hear the sound of the click, provoking my adrenalin to rise in anticipation of a take-off. I know that half my fears have been conquered.

“Blades,” the pilot yells.

“Clear blades, Sir.”

The Huey trembles, gurgles to life. I feel the shaking, magnifying the intensity, putting me under a spell, like a child, of delight. I can fly anywhere, drive on any road, sail in open seas, paddle or swim. My trip to Sulu, yet another one, represents just that at this juncture: a movement.

The grass below us is flattened to a carpet by the sheer force of the Huey’s rotating blades, creating a hurricane on the open field.

Just then, my cell phone beeps. An incoming message, this one I know is from overseas, from a sender who made this morning an exception of waking up before the hour of his body clock because of the difference in time zones, to type this: “Hugs. I remember those rides. Txt when u arrive. U know I do love u.”

That’s the handwriting on the wall, telling me more than anything that we are coming to an end. I have learned to read messages from men, sweet as they sound, bidding goodbye. It so happens, like a ritual, when I am about to go somewhere, on momentous occasions when I am on a turbo-prop airplane at the moment of take-off or a patrol gunship leaving shore on the churning of its engine, as if to tell me that there would be no chance of retrieving the situation, or turning back the clock to prevent the inevitable. It is downright tactful, graceful and sentimental, a buffer to a broken-heart scenario that recalls a script from a black-and-white film.

We are taking off from Edwin Andrews Air Base. When I was a child in the 1970s, I used to watch the frenzy of the aircraft traffic at the height of the Muslim conflict. I looked into the caverns of the C-130 cargo planes and heard the drones of fighter jets. The air base was our amusement park.

So little has changed from memory. We lived in a bungalow just across the main gate and, depending on the season of air missions that I didn’t realize then were part of an operation to destroy an island, men in their rugged Hollywood-like olive overalls and wing insignias hung out at the canteen next door.

As we lift up, I see the golf course and the airport below getting smaller but even in miniature scale, I am able to read a blazing slogan—Adelante Zamboanga.

And at last we fly out towards the vista of a blue-green sea. I inhale the wind, filling my lungs with happiness and putting a sparkle to my eyes. If the helicopter crashes—the thought that hammered in my mind during my all-night anxiety attack—it would be a good thing to be buried in the sea of Sulu.

My mind races back to seemingly inconsequential events that I took for granted this morning: a plateful of deep fried bananas for breakfast on the porch of the Marine Commandant’s quarters, a casual chat with a colonel who is about to retire and who might be looking back on his life when he shows you a picture of his lovely daughter who will soon graduate from college. I go as far back as yesterday, when I was driven from the airport to the Western Mindanao Naval Station where I sat by the breakwater in meditation as the sun set beyond the grey outlines of the moored ships. And with nerves still unsettled, I scoured the pier for a sailor from whom I could snitch a cigarette and a light. By nightfall, when the mosquitoes started attacking by the squadron, the caretaker sergeant called me in. He knew me by now as an occasional guest and hastily cleaned up one of the empty rooms, turning on the air conditioner but forgetting to change the sheets marked with the scent of sweat and pomade left behind by the previous transients.

I have developed this pattern in Zamboanga, like a spell that cannot be broken, of having one too many déjà vus. At bedtime, I relinquished my thoughts to many possibilities, any of which would set a trail of breadcrumbs in my journey. I must remember each one.

The chopper does not crash. We fly above smaller islands, sparse savannahs of green that, when I look at them closely, my mind starts to look for the intricate concept of creation, of diversity, of humanity. Seeing a corner of Sulu from the sky, I take pride and hope. It is not as godforsaken as I think it is, it does not have to be an outcast. The more I see of Sulu, the more certain I am that I have come back for a reason.

In a little more than an hour, we land in an obscure portion of Camp Bautista, in Jolo, on a helipad that is just as untended as the one we came from. It feels as though only wanderers thrive here, a band of chosen travelers. The heat of the tropical morning bears down on us now, an uncanny reminder that we are on an island that is special and different. I wait in the desolateness of the pilots’ lounge until I see the familiar face of a Marine captain walking towards me with a friendly greeting (Yes, he has been here before and I saw him last in Basilan), and pretty soon there are more familiar faces in a waiting convoy stretched an impressive length between the gates of the camp. They’re waiting for me. Run if you can. Get in.

The engines of the convoy are humming simultaneously, as in a chorus. When all is set, it will leave the back exit of Bus-Bus, past a copra warehouse and some adjacent houses of a tight neighborhood, turning out of the city on the single, narrow road to Patikul where wooden houses stand far apart and withdrawn. Every Marine and every soldier who has fought in Jolo knows this road by heart. They know the map of Jolo, the smell of it, the touch of the air, the face of a Tausug to whom this island belongs, and the sound of gunfire. Just by serving on this island, the map will stay in their memory, whether they think good of it or not.

We have gotten acquainted at varying times in the field, these men and I, twice in my sojourn here a year ago, and several times in Tawi-Tawi and Basilan, and further back, about ten years ago, when I rediscovered Jolo under the guardianship of a Marine battalion. And here we are once more.

Camp Bautista lies along the airport, one of the few landmarks of a capital city that is equal in size to a golf course. I read that description in one of the books at the library of Notre Dame College which lies beside the camp, and the image stuck. Imagine an area this size around which the Spanish colonizers built a wall eight feet high, to preserve their foothold in their last years of power. The Americans made Jolo part of their Sulu and Moro Province.

There were too many battles before Philippine Independence and the imprint of violence has remained. In February 1974, the soldiers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines burned Jolo to the ground to quell a Muslim uprising fighting for secession. The fallout from that rebellion has kept the capital in a state of siege where the only presence of government is the military. There has neither been a turning back to the prosperous days or moving forward to healing.

The face of Jolo is as familiar to me as the palm of my hands.

If you see a long parade of armor, trucks, Humvees, jeeps, there is no doubt the Marines are here. On the average, they move with six M-35 trucks, one or two Humvees and armored personnel carriers, and Kennedy jeeps for the officers. This convoy will take me to my destination, about ten kilometers into the municipality of Patikul: a place called Buhanginan, the headquarters of the 5th Marine Battalion Landing Team, which sits by the beach. It is a refuge, a place where, despite the danger around, I can relax and be safe. In is, in fact, called Adventure Resort, the best thing Jolo can claim for a beach resort, and it is open to the villagers on weekends for picnics.

The winds have shifted: there is a change of commanders, the Fleet Marine concept has taken effect. It is, in principle, an amphibious unit, the elite fighting machine of the Navy. But in many stages of military campaigns, with the limitation of resources, standards have had to be scaled back. The battalion landing teams have been re-shaped into territorial forces, staying on land, holding base—pretty much like the Army’s infantry. The Fleet Marine concept has made the geography easier to divide: the Army gets the land-locked territory of mainland Mindanao and the Marines keep the southern islands—Sulu, Basilan, Tawi-Tawi are like vessels from which they operate. They will take this as their playing area, around which is their maneuvering space in water.

In an ideal world, these battalions should have a Landing Ship Tank that can carry about 2,000 troops, a Logistics Support Vessel, a Peacock patrol ship made in England in the 1980s at the cost of about 500 million pesos and whose gun alone costs about 100 million pesos, an oiler, a water tender, and a Balkow-type helicopter gunship that can interdict at sea and is designed for transport and electronic surveillance and whose operational cost alone can put the Navy in the red.

In reality, the Marines do not have such toys, not all at once. The combat service and support group has had to refurbish some war vehicles that had not been running for 15 years. The camp in Buhanginan has a couple of Zodiac rubber boats and a decent sized outrigger—but it cannot see the likes of an amphibious operation in the scale of Saving Private Ryan. Since the Fleet Marine concept has just been put in place, a new birthing after a long study, wrangling over operational control is getting the push and the pull at the Navy headquarters: how much independence should be given to a potent force of about 8,000 men—the size of an Army division? Should they go back to the old tactical idea of having a maneuvering battalion under each brigade as the strike force while the rest stay as a territorial force on their vessel of an island? Should it follow the thinking of senior Navy officers, that all brigades save one (which should train as a maneuvering force) should be part of the naval forces stationed in different parts of the country as it is an archipelago? How far can the Fleet Marine optimize its doctrine? How does it want to make its stand?

Under the Western Mindanao Command, the structure falls under two bodies: the Naval Forces overlooking a Marine brigade in Basilan and a Task Force in Tawi-Tawi with one Marine battalion, and the Joint Task Force Comet in Sulu which has two Marine brigades, a naval task group, and a tactical operations group that can call in special units of the Army.

The 5th Marine Battalion falls under the 3rd Brigade—currently one of two in Sulu, taking the western portion of the island. The camp’s layout is a mockery of the most luxurious resorts in other parts of the country. So you have picnic huts named Dakak, Boracay, etc. The barracks are made of sawali walls, thatched nipa roof, coconut lumber, bamboo. Buhanginan is proud to have a barber shop, a ship store, a medic bay—all functioning at minimum standard. My room—that is, a room for all guests—is the ‘Parang Shangrila,’ equipped with an en suite bath and toilet connected to a second room with two single beds, an air-conditioner that is not necessary because the room steps out to the breeze of the sea, and a bamboo lounge built around a giant tree trunk. This has been my refuge, my own Shangrila. In my daydreams, I often get pangs of homesickness just thinking of it.

A surge of loneliness pulls me down to the spartan bed. This frugal, square box of a room, for all its darkness and mustiness, has known too much of me. I have spoken and wept to the walls, which are lined with blue laminated sackcloth made to look like wallpaper, and, in a pathetic attempt to make it look pretty, someone thumbtacked white lace over it. The quick pace of the day has disoriented me: a breakfast chat with the Commandant before he took off in the chopper I arrived in, a trip to Maimbung on the opposite southern coast for a drum and bugle show under the sweltering heat, a shoot fest at the new firing range right here in camp. I was swept into the energetic thrill of a fiesta, breathtaking and active, when what I am used to is the embrace of the soft waves of the sea.

Dulan is not here; if he were he’d take me for a swim, usually in the late afternoon when the orange ball of a sun disappears into the water. I would tell him to take it easy, I’ve got a deep wound that is still mildly fresh, I won’t be able to do the 20-meter laps between the two mooring buoys. He might then accompany me to the makeshift jetty past the American soldiers’ barracks, just over the camp’s border—where the village boys play in the blue water under the wooden planks, broken now on the edges. This is my private space. Every day I will come here for my short ritual of unburdening myself from the pain, half an hour tops, then I snap out of it and get back to work. Never show your vulnerability to the Marines.

Knock-knock on my sawali door. I unhook the lock. It is a lieutenant, the name on his uniform is Puducay, the battalion’s new staff officer for civil-military operations. He has replaced Dulan, who has been promoted to captain and leads a company in one of the far-flung islands that takes a day of hard travel to reach. I will not be able to visit him.

“Table is ready, Ma’am.”

The wardroom. This is where all things gather to a common purpose. It is exclusive to the officers and the master sergeant that represents all of about 400 enlisted men. This room alternates from a dining area to a war room to a social hall.

The commander sits at the head of a long rectangular table at the end of which is a television set, which is always turned on at mealtimes—to the Wowowee noontime variety show at lunch and TV Patrol at dinner. I take my seat to the commander’s left, surveying the new faces of boys in crew-cuts as they are each introduced to me. The boys in the kitchen already know, from my previous visits, about my nutritional preference, that I am to be served only vegetables. The new commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ferdinand Fraginal, is somewhat an ally who is undergoing a strict regimen himself. We understand each other.

We say grace and proceed to our course of rice and a simple dish or two (fish and soup for the men) and mango or papaya for desert, while the mess boys stand at attention. We need sauce here, more water, a fork please, coffee afterwards. Their plates are empty before I can finish mine.

There used to be a dog named Muffin, whose master, Jerics, the previous commander, would feed with leftovers. Jerics had a rule that anyone who was late at the table would be fined half a case of Red Horse beer that would go to a happy hour binge on a bamboo raft at sea. I could practice my rusty Chabacano with Jerics, who is a native of Zamboanga, the Spanish bastion of the past. Although we are almost the same age and have common friends from childhood, I do not have many fond reminisces of Zamboanga. Sulu calls out to me more. In my youth, the Muslims were pejoratively called ‘Muklu,’ the dirty people.

One thing stands out in the current decor of the wardroom. On a white board is written a Tausug word for the day. The officers are to put each word of each day to memory and make it part of their vocabulary. We are in the land of the Muslim people of the sea current and we must...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

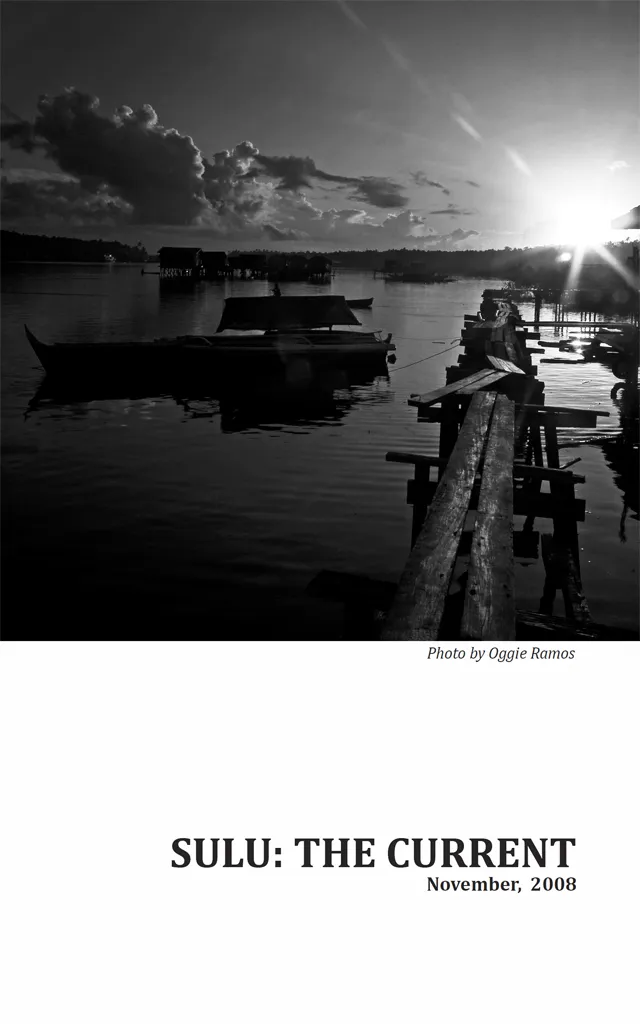

- SULU: THE CURRENT

- SEA STATE ZERO

- LANAO: THE RAIN

- MAGUINDANAO: THE WATERSHED

- THE GULF

- THE MARSH

- EPILOGUE: The Last Touch

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR