![]()

Introduction

I developed renewed faith in the power of psychotherapy after I attended a Traumatic Incident Reduction (TIR) course in 2011. It opened many doors for me as I began to understand the impact of previously overlooked, objectively minor traumatic incidents on psychological disorders and problems. This article is about the application of this powerful tool over the entire spectrum of psychological problems and disorders and how this brings about impressive and permanent change. The optimal use of this tool in psychotherapy requires a shift in epistemology in which we begin to view mental health through a trauma lens. [Epistemology is the study of how we know what we know.]

After numerous sessions of delivering TIR and witnessing its liberating effects on clients, I became convinced that this is the tool of permanent change. The truth is, even after attending the TIR Workshop, one may still fail to appreciate the value of this tool. It was actually only after I started using this tool that I understood its power. Everything fell into place and began to make sense to me. I enjoyed seeing the massive sense of relief and liberation it brought to my clients and, yes, those changes were permanent and didn’t rely on willpower. TIR was more than a tool, it became the lens through which I began to view all aspects of mental health. This trauma lens provided a map for exploring, discovering and resolving the trauma that I came to realize was the culprit behind almost all psychological disorders and problems. In its complexity, I found the simplicity I was looking for. The therapeutic focus became to always de-traumatize to bring about permanent change. Unlike most other forms of psychotherapy, TIR is a subtraction rather than an addition tool. I believe that it is exactly this process that justifies the epistemological shift to understanding mental health through the trauma lens. TIR is about extracting pain rather than adding skills.

As a clinical psychologist trained in an experiential, post-modern theoretical environment, I began my journey in a career as a psychotherapist with a rather disappointing toolbox. In fact, there were no tools in my toolbox. All I felt I had was my inherent ability to enquire, explore, listen attentively, converse and sometimes throw in a few words of what I perceived as wisdom, in an attempt to make a difference. Confusion and despondency were born and grew into bigger monsters after countless directionless conversations with clients. The world of psychotherapy is a harsh one and when we tackle the gigantic task of exploring our client’s world of emotional and mental complexities with no map, we will get lost. I understand that according to postmodern theories, such as the narrative theory, our client’s stories can be bundled together and perceived as neat narratives that we can work with, but the reality is, client’s narratives are extremely complex and we can get lost in that complexity just as much as our clients do. Our clients are in treatment because they are desperate for someone to guide them through the mess and not to get lost in it with them.

I realized that my learning began at the spot where I started my career as a psychologist and I began to take the responsibility to gather tools to put into my toolbox. Yes, of course I knew that experience is a very powerful tool and that I would gain it, but I also knew that experience doesn’t necessarily equal optimal effectiveness in treatment. You can spend many years doing the same thing and not improve at all. A man can work in a factory for 50 years but that does not necessarily mean that after 50 years he can run it.

I attended courses and learned a variety of therapeutic methods. I felt I had become a more effective practitioner, but I still felt uncomfortable as this feeling that I was not helping optimally stuck with me. knew for a fact that there was something very powerful operating in the background that was pulling my clients back into these pits of negative emotions, unwanted patterns of interaction and unwanted habits of thinking and responding and I still did not have the tool to bring about permanent therapeutic change. For me there was a difference between change driven by willpower and change because there was change.

That was my thinking up until the day our manager said she had booked us for a trauma workshop and she wanted us all to attend. I thought, I already had one of the world’s most powerful trauma treatment tools called Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) in my toolbox and it was effective, what would I do with another trauma treatment tool? I was looking for something else. I was looking for an extremely powerful tool to bring about true freedom and the permanent change that I felt was lacking. I did go, however, with an open mind and thought “Well maybe I could learn something new after all”. And I DID. In fact, this tool that I was given turned out to be exactly what I was looking for, the one tool that was still missing from my toolbox, the tool of permanent change. As I continue to explain the power of TIR, it will become clear why I refer to it as the tool of permanent change.

It was actually only after I started using this tool that I understood its power. Everything fell into place and began to make sense to me. I enjoyed seeing the massive sense of relief and liberation it brought to my clients and, yes, those changes were permanent and it didn’t rely on willpower. TIR was more than a tool, it became the lens through which I began to view all aspects of mental health. This trauma lens provided a map for exploring, discovering and resolving the trauma that I came to realize was the culprit behind almost all psychological disorders and problems. In its complexity I found the simplicity that I was looking for. The therapeutic focus became to always de-traumatize to bring about permanent change. Unlike most other forms of psychotherapy, TIR is a subtraction rather than an addition tool. I believe that it is exactly this process that justifies the epistemological shift to understanding mental health through the trauma lens. TIR is about extracting pain rather than adding skills

Looking Through the Trauma Lens

The definition of psychological trauma can vary. From a TIR perspective, trauma can be defined as any incident that had a negative physical or emotional impact on an individual. This is a very subjective issue as the something could be perceived as traumatic by one individual, but as commonplace and harmless by another. The important thing is the emotional and physical impact the incident had on the individual, its subjective impact.

The reason it is so important to view trauma in the broadest way possible is because it explains the chronic mood states of our clients as well as how subconscious intentions and automatic emotional responses affect their current lives. These will be explained below. Traumatic incidents, when understood in the broadest sense possible, have a massive effect on our neurobiology, emotional states and behavioral patterns. Therefore, they can be seen as the driving force behind almost all psychological problems and disorders. When I say traumatic incidents “in the broadest sense possible,” I refer to the everyday incidents of trauma that are objectively perceived as minor, such as an embarrassing comment by a teacher, conflict with a friend, breaking your mother’s expensive vase, etc. It involves an understanding of how the emotional knocks we take on a daily basis affect our neurobiology and continue to have an impact on us in later life. The understanding of subconscious intentions, automatic emotional reactions and responses and chronic mood states are so crucial when it comes to looking at mental health through a trauma lens. Minor and major psychological and physical trauma involves a complex description of the effects on the brain.

First let us look at the subconscious intentions that form as a result of trauma, and how these subconscious intentions continue to affect us throughout our lives. This is one of the most important considerations when we approach psychotherapy through a trauma lens.

Case Study: Jealousy and Rage

Let us look at an example of how intentions are formed and how they affect the individual in later life. A client came to treatment complaining that his wife wanted to leave him because of his pathological jealousy and jealous rages. He said that he had tried to change too many times and promised his wife after every rage incident that he would not do it again and that he would stop checking up on her and being suspicious. He explained how he had no idea why he felt and behaved like that, but that he continued to fail in his attempts to stop these thoughts, emotions and behavior. He was scared to lose his wife and was desperate to get help. Now of course, there are hundreds of different theoretical lenses in psychology through which his problem can be viewed. The lens through which his problem is viewed will determine the therapeutic approach taken to resolve this issue. I hope this example can convince you that the trauma lens is basically the only one that could sufficiently explain and resolve this problem.

In fact, his problem turned out to be trauma-driven. Looking through the trauma lens implies that if an individual is suffering from unwanted negative emotions, thoughts and behaviors, it must be the result of some past traumatic incident. In other words, trauma is behind this. The practitioner’s job is to help the client discover the trauma and then, of course, help the client to resolve it. As mentioned above, trauma shouldn’t be viewed in a narrow way. It includes any and all negative experiences in the individual’s past that lead to the forming of self-protective intentions. The most important task is to discover the root traumatic incident which leads, in this case, to the subconscious intention of not trusting his wife. We had to explore and describe his emotional and behavioral responses in depth so as to open the neural pathways of association with these intentions. In other words we had to discover the incident in which the intentions were formed that kept his jealous rages alive.

We did exactly that and discovered the traumatic root incident during Thematic TIR. [Thematic TIR, discussed in detail later, is designed to trace and resolve current unwanted feelings, emotions, sensations, attitudes and pains]. He was 4 years old and saw his mother kiss a man who wasn’t his father. He became very angry, shouted at his mother, ran to his room and cried upon his bed. It was traumatic for him because he had a very close relationship with his father and, of course, loved and respected him very much. If we look at the intentions formed as a result of this traumatic incident they could be: “From now on I will never trust women” or maybe, “I will from now on always see women as unfaithful” or “Women cheat on their husbands; I will never trust my wife.” We can make an infinite number of guesses about the exact intentions that were formed during this incident, but what we do know is that these intentions continued to affect him for the rest of his life and had a major impact on his romantic relationships, interactions with his wife and subsequently on his marriage and emotional wellbeing.

I’ll explain more the neurobiology of trauma in the section “Amygdala Hijacking”. For now, let us consider that as long as the memories are being controlled by the neurobiological process that involves the amygdala, these intentions won’t go away and can continue to affect him until death. These intentions become stronger over time as the brain reinforces it with other similar traumatic incidents. Can you see how these subconscious intentions can have a massive impact on his relationships? The amygdala cycle in the primitive brain is an extremely powerful force in human emotions and behaviors.

Case Study: Birth Trauma

Examining a birth trauma lets us look a little bit deeper at subconscious intentions and how they continue to affect us: specifically, the case of a woman who suffered from claustrophobia. After an Exploration was done [see Glossary] no root incident was discovered, I asked her to ask her mother whether there was birth trauma. I asked this because I knew there was trauma behind her claustrophobia. I believe there is trauma behind all forms of phobias. In her case the answer was: “My mother said I got stuck during birth.” The storage of trauma can be based on sensory experiences in isolation of language, or concept formation and separate from conscious awareness. Intentions can thus form as early as birth and can continue to affect the individual throughout his life. Pre-language trauma is stored as implicit memories and thus only as a sensory memory. When the senses experience similar stimuli, there will be an emotional response. The intention formed during her birth trauma was that she will from now on always feel anxious when she feels trapped and her brain associated this with other experiences as secondary trauma unfolded, until she reached the point where she was unable to enter an elevator. Of course, not every stuck birth results in claustrophobia. However, from a person-centered point-of-view we accept the client’s interpretation of events as authoritative.

Never Overlook Objectively Minor Trauma

I have witnessed individuals discovering root incidents during Thematic TIR, which left them surprised as to how such a seemingly small insignificant incident could have such a massive impact on their lives. I once worked with a client who was extremely attractive but believed he was hideous and would never find a girlfriend. In fact, he was so self conscious that he couldn’t even take his shirt off on the beach. We discovered the root incident where these intentions formed. It was a comment a friend made about the freckles on his back while they were playing in a sandbox. This happened when he was about 5 years old. Later incidents strengthened these intentions and countless other stimuli that could trigger the traumatic emotional and behavioral responses were included in the trauma triggering cycle. Can you see how when we define trauma in a subjective way and in a very broad way, it opens up therapeutic doors? This is because we acknowledge the influence of objectively minor trauma on our client’s current issues.

Practitioners have the tendency to only look through the trauma lens when major trauma was involved and they forget the subtle, objectively small incidents of trauma and its effect, for instance, the comment about the freckles on my client’s back when he was 5 years old. Not even the client was aware of the impact this had on him, it had to be discovered through TIR along the neural pathway of his current issues. The unfortunate reality is that most individuals are exposed to multiple and sometimes even chronic trauma of this nature, not to mention the effects of more acute traumatic incidents. When the thalamus has interpreted an incident as trauma, it is traumatic for the individual whether it is objectively minor traumatic incidents or major trauma. The understanding of how subtle trauma and its intentions can affect us in later life is what I feel is lacking in our understanding of the impact of trauma on psychological problems and disturbances.

Even in objectively minute traumatic incidents, if the emotional charge associated with them is still high, the amygdala takes over and responds on the basis of the intentions that were formed to protect the individual. When this happens and the rational mind is sidelined, it renders the individual helpless to change. In the example of the jealous man, it was evident that there was a strong desire to change, but a powerlessness to do so. He felt that he must try harder and use more willpower until we realized that his inability to change was the result of a root memory and its intentions that were being controlled by his amygdala. This is why willpower and insight do not equal change.

Amygdala Hijacking -- Why Insight and Willpower Does Not Equal Change

Most practicing psychotherapists realize that insight does not necessarily equal therapeutic change. Personally, I believe that insight doesn’t equate to change at all: understanding makes no practical difference. When we look at psychological problems and disorders through a trauma lens, it becomes clear why. In other words, if my client understood that he felt and behaved the way he did because of what happened to him when he was four years old and that his brain formed intentions that made him feel and behave like this, does this mean that he would be able to stop feeling and behaving like that? Absolutely not! Why not? Because of the force of traumatic memories and the neurobiological processes that are involved when they are triggered. Daniel Goleman (1996) coined the term amygdala hijack to explain the forces of emotional responses. He is considered an expert on emotional intelligence.

Freedman (2010) explains:

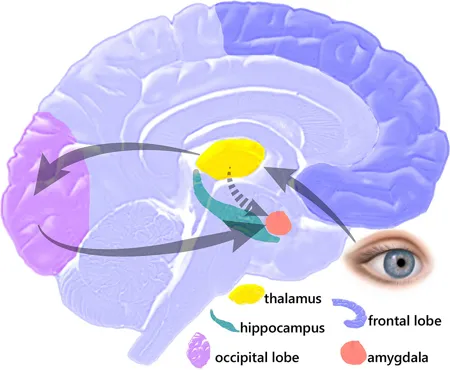

From the thalamus, a part of the stimuli goes directly to the amygdala while another part is sent to the neocortex (the “thinking brain”). If the amygdala perceives a match to the stimulus, i.e., if the record of experiences in the hippocampus tells the amygdala that it is a fight, flight or freeze situation, then the amygdala triggers the HPA axis and hijacks the rational brain. This emotional brain activity processes information milliseconds earlier than the rational brain, so in case of a match, the amygdala acts before any possible direction from the neocortex can be received. If, however, the amygdala does not find any match to the stimuli received with its recorded threatening situations, then it acts according to the directions received from the neocortex. When the amygdala perceives a threat, it can lead that person to react irrationally and destructively.

Fig. 1 - Amygdala Hijack -- Fear caused by optical stimulus

Horowitz (2010) relates:

Goleman states that “Emotions make us pay attention right now—this is urgent—and gives us an immediate action plan without having to think twice. The emotional component evolved very early: Do I eat it, or does it eat me?” The emotional response “can take over the rest of the brain in a millisecond if threatened.” An amygdala hijack exhibits three signs: strong emotional reaction, sudden onset, and post-episode realization if the reaction was inappropriate.

Goleman’s work builds on the earlier findings of Joseph E. LeDoux (1994):

Many of the most common psychiatric disorders that afflict humans are emotional disorders, and many of these are related to brain’s fear system. According to the Public Health Service, about 50% of mental problems reported in the U.S. (other than those related to substance abuse) are accounted for by the anxiety disorders, including phobias, panic attacks, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety. Research into the brain mechanisms of fear help us understand why these emotional conditions are so hard to control.

Neuroanatomists have shown that the pathways that connect the emotional processing system of fear, the amygdala, with the thinking brain, the neocortex, are not symmetrical—the connections from the cortex to the amygdala are considerably weaker than those from the amygdala to the cortex. This may explain why, once an emotion is aroused, it is so hard for us to turn it off at will. The asymmetry of these connections may also help us understand why psychotherapy is often such a difficult and prolonged process—it relies on imperfect channels of communication.

Unlike the U.S. Public Health Service, I believe that a bigger percentage of mental problems could be attributed to trauma. In our case example for instance, pathological jealousy doesn’t appear as a trauma-driven problem, but as we could see it is so. I agree with authors who say that therapy relies on imperfect channels of communication and is therefore such a prolonged process. This is because the imperfect channels are about, firstly, the general tendency to overlook the role of minor trauma in psychological wellbeing and, secondly, not having a tool powerful enough to resolve trauma when it’s discovered. When psychotherapy is approached through the trauma lens right from the outset and when TIR is used as a trauma treatment tool, treatment needn’t be such a prolonged process. It is necessary to understand the impact on mental health of minor traumas and their intentions and not only recognize and address trauma when it is major.

The Failure of Willpower

In addition, therapeutic approaches that rely on the willpower of the client, like for instance conflict management, anger management, cognitive restructuring or any other method designed to help the individual cope with the intensity of his emotions by controlling them or adjusting the way he thinks or responds to them, are, according to my understanding, merely coping tools that won’t bring about permanent change. Primarily, this is because the information the client acquires in treatment functions within the rational mind area and, as we have concluded from Goleman’s description, the rational mind is not involved when trauma is triggered. So yes, we teach our clients skills, and yes they understand them and store them, but the reality is they cannot access that information when it is actually needed; Goleman’s amygdala hijack thus explains why endless conversations about the dynamics of the client’s situation won’t lead to change.

As mentioned earlier, most other therapeutic methods add on to existing structures, while TIR subtracts. Therapeutic attempts that are geared toward hel...