- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Imperial Wars 1815–1914

About this book

Although the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, the world entered a new era of conflict as the newly-industrialised European powers sought to contain the expansion of their neighbours on battlefields that spanned the globe, while the United States laid the groundwork for its future superpower status.The Wars of Empire and Revolt 1815–1914 volume in the Encyclopedia of Warfare Series describes the wars and battles that took place during the height of European imperialism. A chronological guide to conflict on every continent in the century after the fall of Napoleon, the book covers from the South American Wars of Independence to the American Civil War up to the Zulu Wars, the Boxer Rebellion in China and the Mexican Revolution. This volume tells the story of a turbulent century of empire, revolution and civil war. Featuring full colour maps illustrating the formations and strategies used, plus narrative descriptions of the circumstances behind each battle, this is a comprehensive guide to the conflicts of the world. The Encyclopedia of Warfare Series is an authoritative compendium of almost five millennia of conflict, from the ancient world to the Arab Spring. Written in a style accessible to both the student and the general enthusiast, it reflects the latest thinking among military historians and will prove to be an indispensible reference guide.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Wars of Empire and Revolt 1815–1914

Second Barbary War 1815–16

With the War of 1812 concluded, the United States’ powerful and proven navy took the opportunity to deal with resurgent Muslim piracy in the Mediterranean, Congress declaring war against the Bey of Algiers in 1815. Commodore Stephen Decatur’s squadron of nine ships arrived before the news and USS Guerriere combined with Constellation upon this day to maul and capture frigate Meshuda, killing the pasha of the Algerian Navy.

The United States made an example of the Barbary pirates for preying upon American shipping in the Mediterranean. Armed with nine ships and a declaration of war, Commodore Stephen Decatur had the orders and capability to sweep every Algerian ship from the sea. The bey renounced piracy against American shipping in a treaty that was signed on 24 September 1816, on the deck of Decatur’s flagship. 1,083 Christian slaves and the British Consul were freed.

South American Wars 1815–30

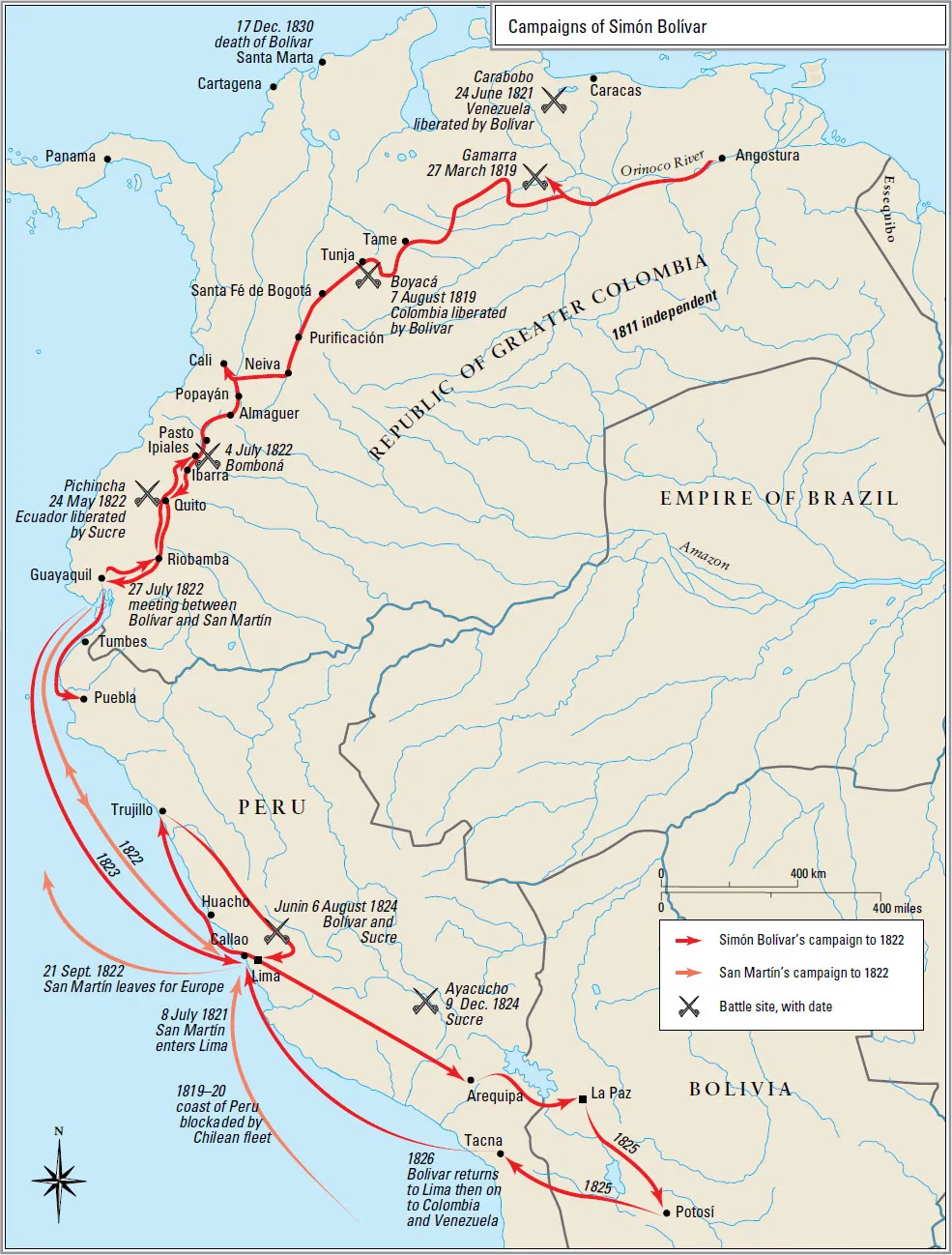

General Simón Bolívar’s liberation of Venezuela received a check here, when a powerful Spanish force – sent out from Europe under Viceroy Pablo Morillo after Napoleon’s surrender – defeated the Venezuelans soundly, forcing Bolivar’s temporary exile to Jamaica.

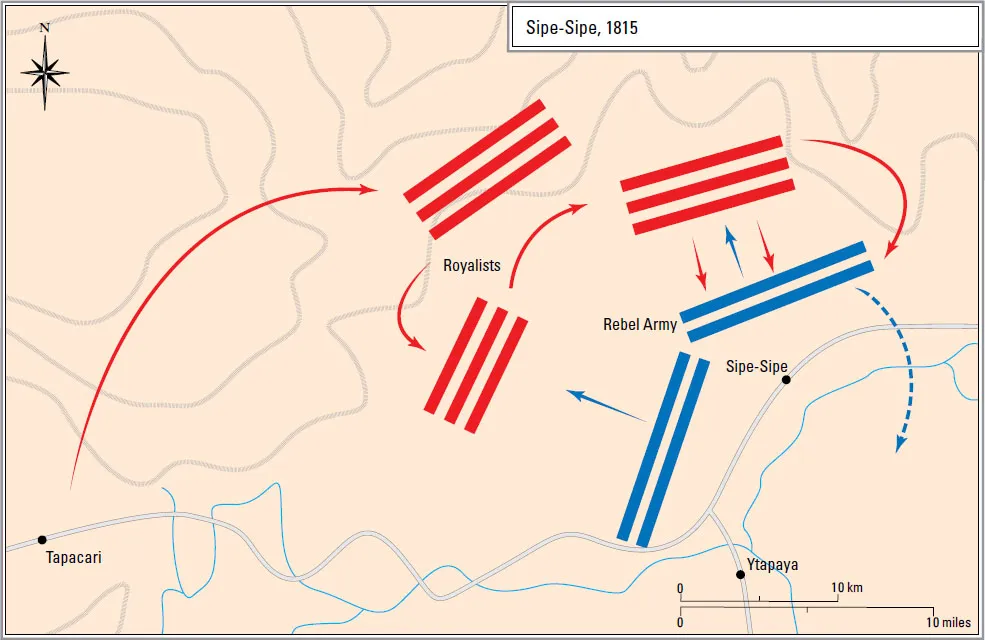

José Rondeau’s United Provinces Army of 3500 men was defeated at Sipe-Sipe (in modern Bolivia) by a 5100-strong royalist army under Joaquín de la Pezuela. The royalists inflicted 2000 casualties for the loss of 230 men.

The rebel Army of the Andes, totalling 4000 Argentine and Chilean troops and 1200 auxiliaries under José de San Martín and Bernardo O’Higgins, made an epic 500km march across the Andes from Argentina to Chile.

The Army of the Andes under José de San Martín and Bernardo O’Higgins defeated Rafael Maroto’s 1500 royalists at Chacabuco near Santiago. The rebels inflicted 1100 casualties for the loss of 100 men.

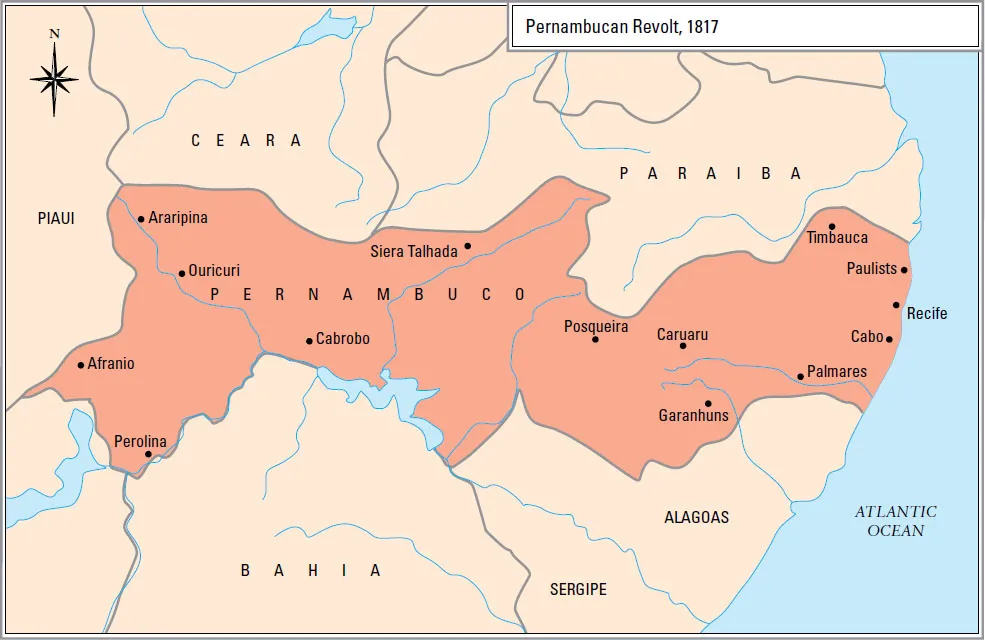

The Portuguese province of Pernambuco in north-eastern Brazil had prospered during the War of 1812 between the United States and Britain, and opened markets for its cotton in Europe. However, as the Portuguese reestablished control after 1815, they once again began to impose restrictions on Brazilian commerce. Tensions grew between Brazilians and Portuguese in Pernambuco, gradually developing into a full-scale movement to establish an independent republic in the region. The rebels formed a provisional government, which sought arms and diplomatic support from Argentina, Britain and the United States. Failing to get international help, the rebels sought support from Bahia and Ceará, but the governors of these regions remained loyal to the Portuguese crown. The Pernambucan rebels abolished titles of nobility, class privileges and some taxes. Although insurgents from Paraíba and Alagoas joined those from Pernambuco, royalist forces quickly suppressed the rebellion.

Don Mariano Osorio’s 5000-strong royalist army decisively defeated the 7000 men of the rebel Army of the Andes under José de San Martín and Bernardo O’Higgins at Cancha Rayada near Talca in central Chile.

Simón Bolívar’s rebel army pursued the royalist forces of Pablo Morillo into Guarico and they met at El Semen, near La Puerta. Bolivar was routed in a bloody action with the loss of 1200 men.

The 5000-strong rebel Army of the Andes commanded by José de San Martín and Bernardo O’Higgins attacked Don Mariano Osorio’s royalist forces, also totalling roughly 5000 men, on the Maipú plains, near Santiago. The rebels won a decisive victory, inflicting 3000 casualties for the loss of 1000 men. The victory ended Spanish control of Chile and allowed Chilean and Argentine rebels to liberate much of Peru from Spanish rule.

The cavalry vanguard of Simón Bolívar’s rebel army comprising 153 men under José Antonio Páez, defeated the 1200 cavalry of Pablo Morillo’s royalist army. The rebels inflicted 400 casualties for the loss of eight men.

Gen Simón Bolívar advanced with his rebel army of almost 3500 men on Bogotá, the capital of Gran Granada (modern Colombia). Anticipating this move, General José María Barreiro’s 3000-strong royalist force marched to intercept the rebel forces.

A foraging detachment of 50 Chilean cavalry under Capt Pedro Kurski was trapped and virtually wiped out by a 200-strong band of Vicente Benavides’ royalist guerillas at Píleo, on the south bank of the Biobío river.

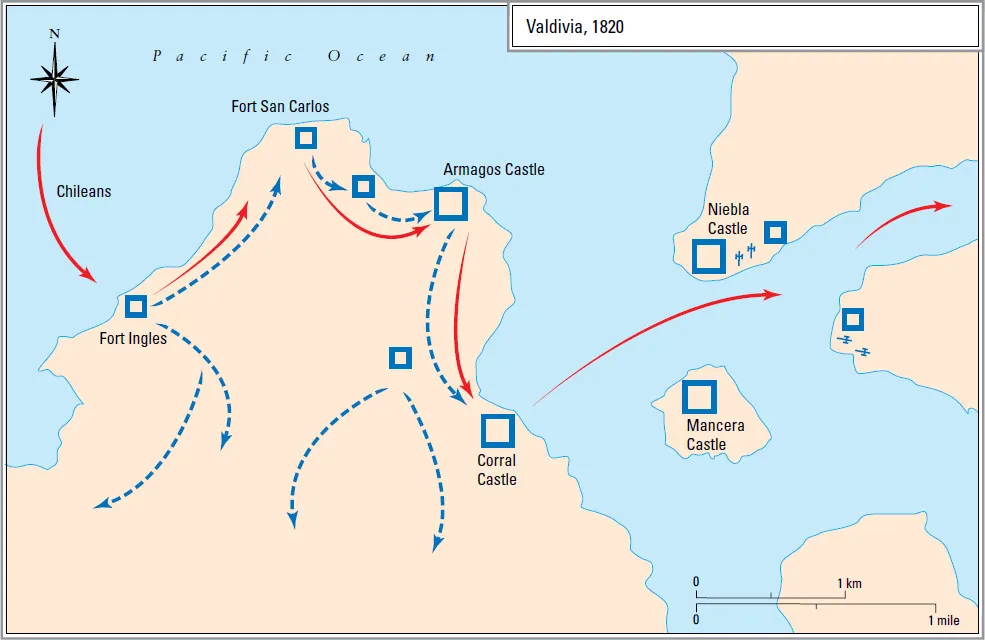

Lord Cochrane, a former British naval officer who had commanded the Chilean Navy since 1818, led a 350-strong landing party that surprised and captured the heavily defended royalist port of Valdivia in southern Chile.

Lord Cochrane’s squadron landed a 60-strong detachment of Chilean marines under William Miller in an unsuccessful attempt to capture Fort Agüi on the Chiloé archipelago, which was held by a royalist garrison under Antonio de Quintanilla.

Jorge Beauchef, the Chilean governor of Valvidia, led a 140-strong detachment south against the remaining royalist forces. The Chileans defeated 300 royalists at the Hacienda El Toro, inflicting almost 150 casualties for the loss of 40 men.

Acting on forged orders, Pedro Andrés del Alcázar’s 600-strong Chilean garrison of Los Angeles evacuated the town and was defeated by 2400 royalist guerillas under Vicente Benavides at the Tarpellanca ford on the Laja river.

Gen Simón Bolívar’s 7500-strong rebel army (including roughly 1000 British Legion veterans of the Napoleonic Wars) attacked a royalist army of 5000 men under Miguel de la Torre that blocked the road to Puerto Cabello (in modern Venezuela). Bolívar attempted an outflanking manoeuvre across rough terrain that was initially beaten off. A further attack by the British Legion routed the royalist forces, inflicting 2900 casualties for the loss of 200 men.

Antonio José de Sucre’s 3000-strong rebel army defeated 1900 royalists under Melchior Aymerich on the slopes of the Pichincha volcano, near Quito (in modern Ecuador). The rebels destroyed the royalist army for the loss of 340 men.

Expatriate British admiral Thomas Cochrane’s services and long experience against Napoleon proved useful to more than one coastal South American country during the series of revolts that left Spain and Portugal at the end reft of their empires in the southern hemisphere. After service with Chile and Peru, Cochrane accepted an appointment as First Admiral of the Brazilian Navy in March 1823. Cochrane immediately experienced great difficulties with sub-standard ordnance and ammunition. A bigger obstacle was the insubordination of South American officers, who, during a revolt against Europe, became disgruntled with serving under a European and resentful of Cochrane’s sudden superior rank. Cochrane faced a powerful Portuguese squadron comprising ships mounting 75, 50 and 44 cannon, with five smaller frigates and six lesser vessels. This flotilla took possession of Bahia on the Brazilian coast as the restored Portuguese government sought to reassert its control in Brazil. Cochrane’s untried squadron of seven ships consisted of vessels mounting 74, 32 and fewer guns. Cochrane found his move to blockade Bahia countered by a sortie of the entire Portuguese squadron, which sailed forth to meet him in line. Nonetheless, in the largest vessel, the Pedro Primiero, Cochrane sailed Nelson-style through the approaching Portuguese, signalling to the rest of his squadron to support him in isolating and destroying the four vessels at the end of the enemy line. Instead, Cochrane found himself battling the entire enemy squadron when his subordinate commanders ignored his orders to engage. Defective munitions and unskilled gunners frustrated Cochrane’s attempt to damage the nearest Portuguese, while the Portuguese serving in the magazines denied powder to the guns. Cochrane withdrew and launched a reformation of the Brazilian Navy into a capable fighting force.

Adm José Prudencio Padilla defeated a royalist squadron under Capt Ángel Laborde on this Venezuelan lake, the rebel forces and royalists exerting considerable effort in what proved to be the last battle of Venezuela’s liberation.

Generals Simón Bolívar’s and José Canterac’s royalist cavalry employed lance and sabre in this battle in Argentina. Bolívar’s hussars saved the day as Canterac’s lancers drove the patriots back by attacking from the royalists’ rear.

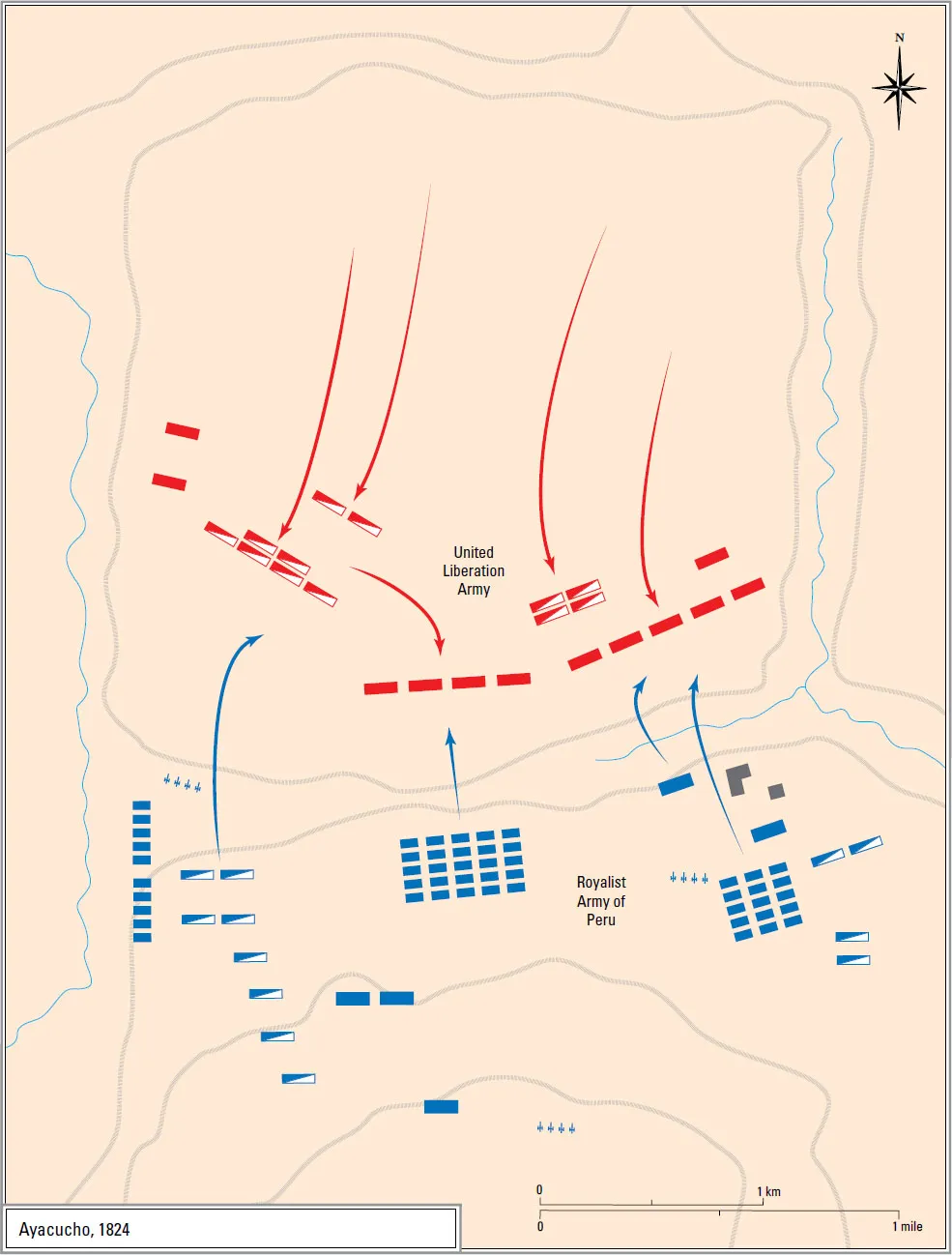

In this, the final, decisive battle for Spain’s control over South America, Spain’s last viceroy, José de La Serna e Hinojosa, led Spain’s last effort to retain control of at least the southernmost portion of the New World in Peru. De La Serna and Antonio José de Sucre (Simon Bolívar’s most talented subordinate) gathered their forces, the rebels securing some advantage by mustering in the Andean highlands and acclimatizing to the very high altitude. The two roughly even armies then manoeuvred against each other among the rivers and around the plateau of Ayacucho, each seeking geographic advantage. Both sides took their time in selecting a proper battlefield. The royalists occupied the proverbial high ground with well-equippe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Maps

- Foreword to the Series

- Wars of Empire and Revolt 1815–1914

- Authors and Contributors

- Consultant Editors

- How to use the Maps

- Key to the Map Symbols

- Battles and Sieges Index

- General Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app