§1 A Budget for Boom Bust

MARCH 17, 2004, 12.30pm: the dispatch box of the House of Commons. Gordon Brown rose from the green bench occupied by ministers of Her Majesty’s Government. This was his eighth budget, and the last day on which he could announce a remedy for the looming boom bust. Would he vindicate his claim to be the prudent Chancellor of the Exchequer who had balanced the nation’s books and steered Britain around the recession of 2001? Or would he fail the test that he had set for himself as head of the Treasury? The contents of Brown’s speech would determine Britain’s economic fate for a decade. He had left it to the last minute. By my calculations, he had three years in which to introduce legislation and implement a pre-emptive strike against the violent beasts that lurk inside the capitalist economy – the booms and busts.

Twice before, in 1909 and 1931, Brown’s predecessors had legislated changes to taxes that laid the foundations for sustained growth. But the reforms were expunged from the law books because of the implacable opposition of the peers of the realm. This time, it could be different. Tony Blair’s government had a majority in the Commons of 159 MPs. And he had dismantled the blood-line buttresses that protected the privileges of the House of Lords. All that the government now needed was for Gordon Brown to act as a tough-minded chancellor to reform public finances in a way that would finally shift real power to the people.

The chancellor knew where to look for the vulnerable points in the economy. A year earlier, he correctly identified the issue that defeated his predecessors. They had strained to deliver full employment, but were repeatedly thwarted by activity in the housing market. When Brown stepped into the Treasury building in Parliament Street, at the bottom of Whitehall, in 1997, he was determined not to suffer that ignominy. He asked his civil servants to analyse and learn from the business cycles that terminated in recessions. He revealed their findings in his budget speech on April 9, 2003. Brown compared Britain’s record with countries like France and Germany, and drew this conclusion:

Most stop-go problems that Britain has suffered in the last 50 years have been led or influenced by the more highly cyclical and often more volatile nature of our housing market.

Politically, this diagnosis helped Brown to defer a decision on an awkward problem. He used the housing cycle as a reason to delay the announcement on whether Britain should abandon sterling in favour of the European Union’s currency, the euro. Britain needed to synchronise itself into the continent’s housing markets, which were less prone to violent price swings. Then Britain could contemplate locking herself into Europe’s monetary system. But the decision to use the housing market to stall on the euro exposed the void in Brown’s policies. Now, he would have to explain how he would prevent the next housing boom bust. With prices at the beginning of the decade rising at annual rates of 20% or more, the housing market was ‘overheated’. What could be done to prevent similar price rises at the end of the decade, prices that would initiate a wild spending spree and the downturn in the years from 2008 into the trough of 2010? To search for solutions and buy more time, Brown commissioned reports from two eminent economists on the financing and supply of residential property. The results of those enquiries were in his hands when he stood up to address the House of Commons on March 17, 2004.

The parliamentary sketch writers in the Press Gallery were preoccupied by the sub-text of the budget speech. Gordon Brown was pitching for the top job in government. He wanted to move into No. 10 Downing Street lock, stock and barrel. He already lived in the small apartment above No. 10, by agreement with Tony Blair. But he also wanted to occupy the Prime Minister’s office. Practically everything that he had done during the seven years of his chancellorship was weighed in terms of whether they would affect his prospects of becoming Premier. Brown’s political future was bound up with the health of the economy.

His first task was to establish – and advertise – his credentials as the master craftsman of economic management. Since 1945, he told the law-makers who packed the Commons, Britain had repeatedly lapsed into recession, moving from boom to bust.

But I can report that since 1997 Britain has sustained growth not just through one economic cycle but through two economic cycles, without suffering the old British disease of stop go – with overall growth since 2000 almost twice that of Europe and higher even than that of the United States.

The Presbyterian Scotsman was not averse to singing his own praises. He was triumphant as he pronounced his willingness to confront the ‘tough decisions’ head-on. As a result, he had entered the history books as the architect of a strategy that would deliver prosperity uninterrupted by the downturns that had caused misery for millions in the past.

But there was more to come. Gordon Brown’s achievements were even more awesome.

Having asked the Treasury to investigate in greater historical detail, I can now report that Britain is enjoying its longest period of sustained economic growth for more than 200 years … the longest period of sustained growth since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

Here was a claim of historic significance. Earlier generations of economists and finance ministers had struggled to find the secret of sustainable growth. The formula had eluded them. And then along came Gordon Brown, the heir apparent to the New Labour throne, and the magical formula was pulled out of the red ministerial briefcase.

It was all an illusion. Gordon Brown had not introduced the reforms that could neutralise the propensity of the economy to surge to the peaks that terminate in a valley of tears. Having failed to set in place the preventive measures, the Brown boom bust of 2005-10 would go down in the history books as yet another dismal failure in the quest for sustainable growth.

But that outcome was not on the minds of the journalists who gathered to hear the chancellor. Most of them were willing to declare him a competent master of the art of economic management. The challenge for Brown was to maintain that illusion. How would he perform his sleight of hand? The eagle-eyed politicians on the benches of Her Majesty’s Opposition failed to spot the crafty juggling that lulled the nation into thinking that it was in safe hands. The financiers in the City of London also failed to realise that Brown’s micro-management techniques had fostered the formative stages of the most traumatic phase in the business cycle.

To expose the interior flaws in the policy edifice that he constructed with meticulous care, we will apply Brown’s own tests.

- A government that permits volatility in house prices is locked into the stop/go cycle.

- Two hundred years of historical evidence affords the evidence for exposing the fatal weaknesses in the foundations of capitalism.

We will push the evidence even further back, and scrutinise Brown’s stewardship by examining 400 years of economic history. In doing so, we will reveal that Gordon Brown, by his acts and omissions, allowed the gnawing virus at the base of the industrial economy to flourish. He failed to stop people from speculating in the capital gains that could be captured in the housing market. The downturn in economic activity that would follow from this frenzied activity would drive large swathes of the middle classes into financial crises on an unprecedented scale.

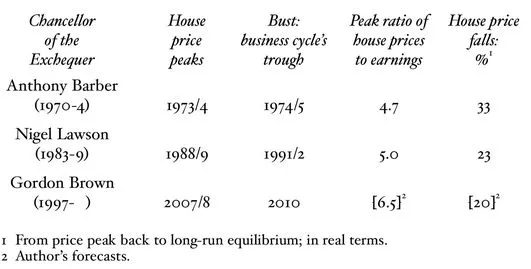

This happened twice within living memory. Two Tory chancellors, Anthony Barber in 1970 and Nigel Lawson in 1983, also thought they could defeat the logic of the business cycle. In fact, they entered the Treasury as hostages to a historical process which – if it was not neutralised – would irrevocably associate their names with severe economic volatility (Table 1.1). In each of the post-World War II housing boom busts, house prices became so unaffordable that they had to plummet – dragging the rest of the economy down with them.

TABLE 1.1

UK Housing-Driven Boom Busts

The drop in the real value of houses in the mid-’70s was camouflaged. Superficially, the problems began when the Heath government decided to liberalise the financial system in the Competition and Credit Control reforms of September 1971. Record level wage settlements funded by a pliable credit-creating system meant that mortgages and other loans could be eroded away by roaring inflation. But disguising the drop in the real value of people’s homes did nothing to moderate the pain felt by those working people who, having struggled to buy their homes, were thrown onto the dole queues.

This ought not to have happened in the 1980s. Margaret Thatcher and her finance ministers were hard-line monetarists. They would not countenance Anthony Barber’s profligate pump-priming policies. And yet, they did preside over a classic housing-fuelled consumer boom. Nigel Lawson took the blame. He did, after all, have sufficient time in the Treasury to propose remedial measures. This time, however, the freefall outcome was not so well disguised by inflation: as prices crashed, the homes of hundreds of thousands of families were repossessed because they could not afford to maintain mortgage payments. John Muellbauer, an economist at Nuffield College, Oxford, was one of the few who tried to sound the alarm bells. The house price/ consumer debt nexus could be read in the statistical record, but there was something more specific about the nature of the problem that he felt ought to be highlighted.

Land speculation plays its part too; as prices rise, some land is held back in the hope of being able to sell at a higher price later. After the peak, land prices fall sharply as owners try to sell while prices are still high. The 1971-73 boom followed by the 1974-76 slump was a classic instance of instability.1

The third postwar boom bust will be irrevocably associated with the presiding New Labour chancellor, Gordon Brown. In the reported agreement he had with Tony Blair, in return for not competing for the leadership of the Labour Party he would be responsible for domestic policies when and if they came to power. Whatever the truth about that deal, Brown did, indeed, through his control of the public purse, preside over the domestic political agenda. One result was the boom in house prices which priced low-income first-time buyers out of the market in 2002. They were replaced by middle income speculators who invested in buy-to-let apartments. When the property market paused in late 2004 they, in turn, were replaced by relatively rich buyers of property. Thus began the elevation of the ratio of house prices to earnings towards new records. Symbolically leading the rush upwards was Tony Blair and his wife Cherie. When they bought a house in Bayswater in September 2004 for £3.6m, City Editor Robert Peston calculated that ‘they are borrowing about six times their combined income’.2 Others would emulate the Blair family’s willingness to go deep into debt to the point where, when the collapse came, many of them would be bankrupt.

This outcome could have been avoided. Gordon Brown, if he did not wish to join the list of failed chancellors, had a maximum of seven years in which to implement the remedies that could reshape the housing market. In opposition, he methodically planned the party’s economic strategy to the finest detail. Nothing could be left to chance if Labour wanted to return to power. At the election in 1997, the voters decided to give the Blair team its chance. And Gordon Brown’s first act on arriving at the Treasury was to announce the independence of the Bank of England. There would be no political tampering with the money supply. In future, interest rates would be set by a Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) composed of eminent economists. Brown set the target inflation rate: 2.5%. The central bank just had to keep inflation at, or close to, this level, and expansions of the money supply of the kind that fuelled the Barber and Lawson booms would be consigned to history.

But that 2.5% target – which had to be met ‘at all times’3 – was defined by Gordon Brown to exclude mortgage interest payments on houses. The official definition of inflation included the depreciation of the bricks and mortar but ignored the appreciation in the value of land beneath the buildings. Here was a puzzle. House prices, which determine the size of people’s mortgage debt, are not independent of inflation. Stephen Nickell, a professor at the London School of Economics who served as a member of the MPC, explained the connection.

House prices in Britain are currently [2002] rising extremely rapidly. This house price boom has had, and is having, an impact on monetary policy and interest rates because house prices impact directly on consumption and aggregate demand, and hence on future inflation prospects.4

If the Bank of England had been legally obliged to include all the...