![]()

German reservists head to war. The German war plan made much greater use of reservists than did the French. This gave the Germans more men in front-line units, but demanded a gargantuan effort from men who had been out of the army for many months or years.

CHAPTER 1

The Schlieffen Plan

The war began with many soldiers and politicians believing that it would be like the Wars of German Unification in the 1860s and 1870s – bloody, but lasting just a few months. They had accordingly planned for offensive warfare and most had not expected to fight more than one large campaign.

Beginning in the 1890s when Franco-Russian relations began to grow warmer, German generals became haunted by the prospects of fighting a two-front war. Although they knew that they could take advantage of what strategists call interior lines by moving men between the French and Russian fronts along Germany’s excellent east-west rail network, the generals understood that Germany would be at a severe disadvantage in a lengthy two-front war. They began strategic planning with this concern at the forefront and added to it two other guiding assumptions: that the Franco-Russian alliance meant that any war with France or Russia meant war with both, and that one of the two would need to be defeated quickly in order for Germany to focus its military assets against the other.

After 1894, Count Alfred von Schlieffen, the chief of the German general staff, drew the logical conclusion that Germany could not count on a quick defeat of Russia. For Schlieffen (born in 1833) and officers of his generation, the Napoleonic experience in Russia presented an absolutely nightmarish vision of endless operations with tenuous supply lines deep into the interior of a barren and hostile country. From these beginnings, Schlieffen came to another conclusion: Germany’s best chance to avoid a two-front war involved attacking France first. He believed that France’s capital, Paris, was within Germany’s reach, and that its capture would win the campaign. On the other hand, he was enough of a student of history to know that Napoleon had marched through Moscow without winning a war. Moreover, he assumed that the large, but slow-footed Russians were incapable of a rapid mobilization, whereas the French could use their excellent railway network to concentrate forces against the German border. France thus had to be beaten first.

Count Alfred von Schlieffen bequeathed to the German Army an offensive war plan that called for an attack on France regardless of the diplomatic crisis leading to hostilities. His plan, which included an invasion of neutral Belgium, converted a Balkan crisis into a Continental war.

The German General Staff

After the Napoleonic Wars, the Prussian Army reformed itself to encourage the recruitment and formal training of future staff officers on merit alone. This system proved very successful under von Moltke the elder, and was adopted by the Imperial German Army upon its formation in 1871. The best young officers were systematically trained in strategy, tactics, logistics and administration so that a brief command from a general would be enough for his orders to be carried out. Critics have argued that this encouraged over-rigid planning.

The biggest impediment to a German invasion of France rested in the powerful French fortifications that covered the major river crossings and rail centres from Verdun to the Swiss border. To avoid them, German forces would need to move to their north, but the space between Verdun and the Belgian border provided too little room to move forces and supplies in the numbers the Germans would need. Schlieffen thus decided that the invasion of France would require an invasion of neutral Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg. In so deciding, he effectively tied the hands of future German diplomats, few of whom were privy to the details of war planning.

Schlieffen designed an operation that would function as a swinging gate, with the ‘post’ anchored in Alsace. The rightmost units of the German sweep would move along the English Channel through the Low Countries, swing north and west of Paris, then turn southeast, enveloping the French capital and trapping any French resistance inside a giant double pincer. The German right would act as the hammer, while the left (the ‘post’) would be the anvil. To ensure that his plan would have the forces needed to win this campaign in a mere six weeks, Schlieffen dedicated to it 1,750,000 men of the two million-man German Army he hoped to build. Once France had fallen, hundreds of thousands of these troops would be entrained and moved east by rail in time to defend the German eastern frontier against the now mobilized Russians.

The Schlieffen Plan, modified by subsequent German commanders, demanded an almost impossible effort by German soldiers. They were to wheel around Paris and force the French out of the war in a mere six weeks. It took little account of the famous fog and friction of warfare.

The plan was far too risky and rigid, leaving little room for the fog and friction that always accompanies any large-scale human endeavour. It also presumed that Germany would have to make quick decisions, perhaps even beginning military operations before war had been officially declared in order to give such a precarious plan the best chance of success. Consequently, the plan subsumed domestic politics, foreign policy and even grand strategy to the immediate operational need of the army to deploy into neutral nations as soon as possible. The details of the plan were closely guarded, and there is substantial evidence that even Kaiser Wilhelm failed to realize all of its implications. Rigging war games so that the Kaiser’s side always won did little to help him understand the military’s many complexities.

Schlieffen retired in 1905, leaving the plan in the hands of a scion of one Germany’s most legendary military families, Helmuth von Moltke (the younger). Moltke cancelled the invasion of Holland in order that Germany might have a neutral neighbour through which it could trade with the outside world. This change indicates that Moltke at least recognized the possibility that the plan might not work and that Germany might have to fight a two-front war after all. Under Moltke’s modifications, seven-eighths of the German Army would march west on the outbreak of war, whether the cause of the war was in the west, the east or even overseas, but Moltke placed fewer men on the extreme right wing of the advance in favour of assigning more men to the German left in Alsace and Lorraine. He appears to have been afraid of either a French breakthrough in the region or the impact on German morale if the French managed to take a symbolic city in the region such as Strasbourg or Metz.

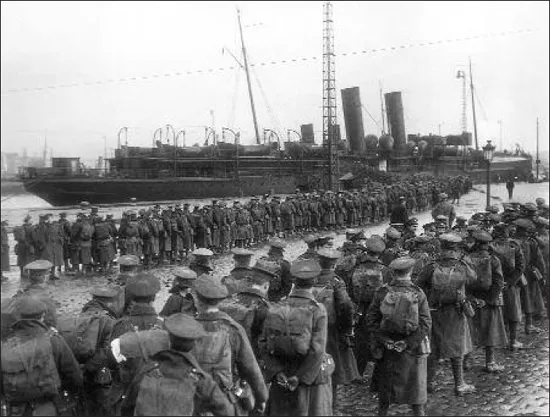

The professionals of the British Expeditionary Force embark for France in 1914. The men were highly skilled soldiers, but their commanders had only worked out rudimentary arrangements with their French allies and had no shared war plan to implement.

The plan’s call for an invasion of Belgium meant that it risked bringing the British into the war, but German soldiers showed little concern. If the war went as quickly as envisioned, then the entry into the war of the British would make little difference, as the Germans would be in Paris, sipping champagne and drafting one-sided peace terms long before the Royal Navy could put a blockade into effect. Moltke disregarded the small BEF, whose 100,000 men would make little difference in the face of nearly two million Germans. He assumed that the BEF would be swept up along with the Belgians by any advancing German forces. A disregard for the British Army ran rife through the German high command, with the Kaiser later dismissing the BEF as a ‘contemptible little army’. Moltke himself once stated that if the BEF dared to deploy to the Continent he would send the Berlin police to arrest them. If, however, Moltke’s plan did not work, then the vast resources of the British Empire, including the manpower of India, Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, might come into play. Even in his wildest imaginations, Moltke must have known that the Berlin police did not have enough handcuffs for that job.

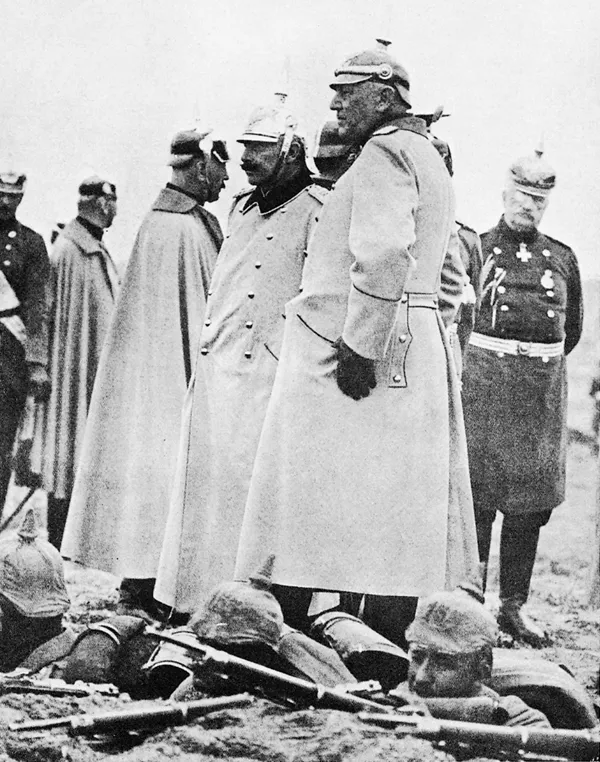

Helmuth von Moltke (the younger) (1848-1916)

Moltke seen here with the Kaiser. Moltke always harboured doubts that the Kaiser had given him command of the German Army based more on his famous lineage than his abilities.

The chief of staff who replaced Schlieffen was the nephew of his namesake, the Helmuth von Moltke (the elder) who had designed Prussia’s rapid victories in the wars of German unification (1864-71). The new chief of staff lacked Schlieffen’s gambler’s touch and made several modifications to the plans he inherited. Moltke had less confidence in himself and in the presumed superiority of the German Army over its French counterpart than his predecessor had. He is supposed to have reacted to his appointment by asking Wilhelm if he truly expected to win twice at the same lottery, an indication that he felt his job was more as a result of his famous name than his qualifications.

‘It is my Royal and Imperial command that you concentrate your energies [and] ... exterminate first the treacherous English and walk over General French’s contemptible little army.’

Army order issued by Kaiser Wilhelm II, 19 August 1914

Neither the Germans nor the Austrians were fully privy to their most important ally’s war plans. Consequently, while the Germans were planning to focus almost all of their energies on France, the Austrians were planning to move the vast majority of their forces south toward Serbia. If, as in fact happened, the Russians proved more adept at mobilizing than the Germans predicted, then no large-scale formations would be in a position to stop Russian forces from invading East Prussia, the traditional home of the German aristocracy, or the Hungarian breadbasket that would be critical to feeding soldiers and civilians alike if the British were able to put an effective blockade into place.

In late July when the Germans were considering their military options, Kaiser Wilhelm at first asked Moltke if the army could prepare for operations in the east only. Moltke informed him that such a deployment was not possible; every aspect of German war planning and resource allocation had been hardwired for years to attack France first. Changing strategic direction at such a late date and without any appropriate war planning would cause tremendous confusion and traffic tie-ups. Wilhelm looked at Moltke and icily said ‘Your uncle would have given me a different answer’, although he had no choice but to accept Moltke’s assessment of the likely outcome of any late changes.

The magazine rifle was supposed to be the main weapon of the war. Especially when fitted with a bayonet, it was supposed to be an expression of the individual soldier’s élan. In the end, however, most soldiers would be killed by more impersonal weapons like machine guns and artillery pieces.

THE GERMAN INVASION OF BELGIUM

The Schlieffen Plan as finally implemented divided the German Army into eight field armies. The German First Army would be the strongest, containing 320,000 men. It would sweep through the Belgian cities of Louvain and Brussels, cross into France near Lille and be on the Seine River northwest of Paris in just 37 days. Operating just to its south, the Second Army would clear the Belgian fortress cities of Liège, Namur and the French fortress at Maubeuge, arriving on the Oise River north of Paris shortly after the First Army had reached the Seine. The German Third Army would advance to Soissons, the Fourth to Reims and the Fifth to the Argonne Forest just west of Verdun. The left wing of the German Army, the Sixth and the Seventh Armies, would hold prepared defensive positions in Alsace and Lorraine. Only the German Eighth Army would deploy to the east to keep the Russians at bay until the surrender of France permitted German reinforcements and new call-ups to move east.

The Schlieffen Plan was only part of the war’s early months. The French responded with their own plan, Plan XVII, which concentrated force in the centre. French troops advanced into the ‘lost provinces’ of Alsace and Lorraine with little gain and huge casualties.

The ambition of the Schlieffen Plan is breathtaking. It demanded superhuman efforts from German soldiers, few of whom were in the hardened physical shape they would need to make long forced marches against active opposition. To increase the number of men in the field armies, the Germans planned for extensive use of reserve troops, whose training and physical fitness were both considerably inferior to those of first-line troops. German logistical preparations, moreover, were wholly inadequate to the task of keeping hundreds of thousands of men supplied. Most importantly, the Schlieffen Plan, by drawing the British and French empires into a conflict that did not involve their core interests, converted a Balkan crisis into a world war.

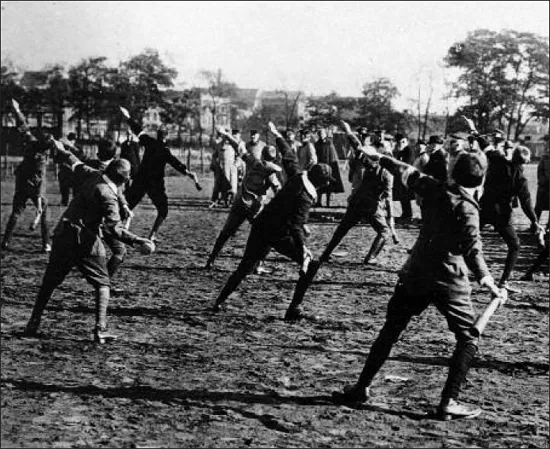

German schoolchildren learn how to throw bombs during hand grenade training. Grenades were an integral part of trench warfare, allowing men to hit targets underground or around the blind curves of a trench system. Grenades could also be launched from a rifle or dropped out of an airplane.

FRENCH WAR PLANS

The French had guessed the general outlines of the German plan. They envisioned that the Germans would indeed avoid the powerful French fortifications and try to outflank the French by moving through Belgium. On taking command in 1911, French general Joseph Joffre discarded his predecessor’s essentially defensive French war plan, known as Plan XVI. He had concluded that the French Army would need to be more aggressive and more offensively minded in the opening weeks and months of war for two reasons. First, the French Army, he believed, had a moral obligation to liberate the ‘lost provinces’ of Alsace and Lorraine, which the Germans had taken from France in 1871. Although few Frenchmen in 1914 sought war to recover the provinces, once war began their reconquest became a war aim that Frenchmen of all political stripes could rally around. Second, Joffre believed that the French Army had to conduct an offensive in the early weeks of the war to prevent the German Army from deploying massive resources on the Eastern Front until the Russians were mobilized and ready to meet the challenge.

Joseph Joffre (1852-193...