![]()

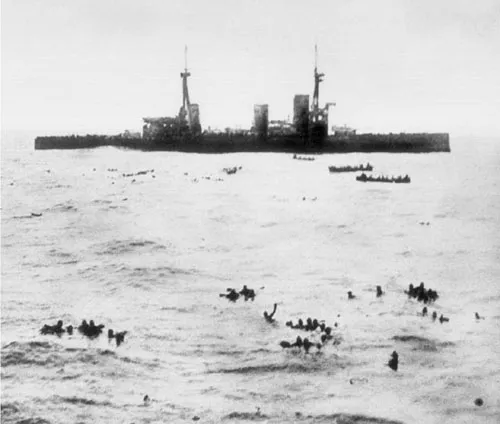

Survivors from SMS Gneisenau floating in the water during the Battle of the Falkland Islands, 8 December 1914. The early months of the war saw two major engagements take place far from European waters; the first (Coronel) was a German victory, the second (the Falklands) a British one.

CHAPTER 1

Distant Waters

At the start of the war in August 1914, there were three challenges to the Royal Navy’s command of the seas: German cruisers stationed outside Europe, the German battlefleet based across the North Sea and the novel threat of the submarine. While in northern European waters, the opposing battlefleets remained cautiously outside their opponent’s reach, in more distant waters the threat from the cruisers would dominate the opening stages of the war, predominantly in the Indian, Pacific and South Atlantic oceans.

The Royal Navy had long deployed powerful squadrons on many overseas stations. Despite Fisher’s rebalancing of the fleet, the outbreak of the war still saw British warships spread across the world, although these were not first-rank ships. Their responsibilities were considerable and widespread, though they benefited from an impressive network of bases and support facilities.

Germany, albeit on a smaller scale, had sought to gain diplomatic benefits from her growing naval power. In the early years of the century, her warships had seen action in the Far East and the Caribbean, and off South America and North Africa. At the beginning of the war, Germany had a number of cruisers patrolling foreign waters. The light cruiser Königsberg was off East Africa, the Dresden was in the western Atlantic and the Karlsruhe was en route to relieve her. Their standing orders in the event of war were to conduct classic cruiser operations against enemy commerce. The idea of creating a chain of fortified bases from which these ships could operate had been dropped, in view of the high probability that such bases would fall and any warships stationed there would be lost. As an alternative, Germany built up a network of agents in neutral ports to arrange the supply of fuel, food and other materials.

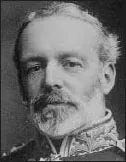

Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee (1861–1914)

Spee was born in Copenhagen to a noble German family (‘graf’ equates to ‘count’) and entered the Imperial German Navy in 1878. He was a gunnery specialist who gained much experience in overseas service. This was to stand him in good stead in 1912, when he was appointed commander of Germany’s principal overseas naval force, the East Asiatic Squadron. On the outbreak of war, Spee took this powerful, modern force across the Pacific – a formidable achievement in terms of arranging refuelling and resupply in an increasing hostile region – before reaching the coast of Chile. Here, at the Battle of Coronel he inflicted on the Royal Navy its first defeat in over a hundred years. Thereafter, he steamed into the South Atlantic, where he took the risky decision to raid the British base at the Falkland Islands. The resulting battle cost Spee’s life and also those of his two sons, who were serving in other warships of the East Asiatic Squadron.

Spee (left) was responsible for an early boost to the prestige of the Imperial German Navy, but it was only a matter of time before his force was run to ground.

SPEE IN THE PACIFIC

Germany’s principal overseas force was the East Asiatic Squadron, under the command of Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee. It operated from the only major German overseas base at the fortified port of Tsingtao (Qingdao) in China. This force was centred on the modern armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, each displacing 12,900 tonnes (12,700 tons) and carrying eight 8.2in and six 5.9in guns, with light cruisers in support. Both had well trained and experienced crews, and their gunnery was impressive even by the high standards of the German Navy.

Britain had powerful forces east of Suez, but, reflecting the importance and spread of its trading and imperial commitments, these were widely dispersed. Thus, the China Station had a force including the pre-Dreadnought Triumph (armed with comparatively feeble 10in guns) with two armoured cruisers and two light cruisers; the East Indies were protected by the battleship Swiftsure (sister ship of Triumph), with two light cruisers; and Australia and New Zealand contributed a battlecruiser and four light cruisers. Many of these ships were effectively obsolete, but in wartime they would be reinforced by Allied vessels from the French and Russian navies, and perhaps even the powerful and modern Japanese fleet. Furthermore, the British Grand Fleet provided distant support by hindering additional German cruisers in their efforts to menace the shipping lanes. The Admiralty was well aware of the strength of the German East Asiatic Squadron, viewing it with a wary respect, and realized that British forces would need to concentrate to be sure of defeating it.

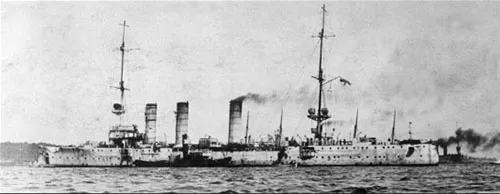

As part of Spee’s East Asiatic Squadron, the light cruiser Nürnberg finished off the badly damaged HMS Monmouth at the Battle of Coronel. At the subsequent Battle of the Falkland Islands she sought to escape, but was chased down and sunk by HMS Kent, inflicting some damage in return.

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock (1862–1914)

Cradock joined the Royal Navy at the tender age of 13. His formative experiences ranged from fighting ashore in Egypt and the Sudan, to helping suppress the Boxer Rebellion in China, to serving on the Royal Yacht. He also found the time to publish three books. Cradock was an experienced and brave officer, popular with his crews and his fellow officers and well regarded by his superiors. In 1913, he was appointed to command the North America and West Indies Station, becoming responsible on the outbreak of war for protecting shipping over a huge area. His action at the Battle of Coronel, leading the British force from his flagship HMS Good Hope against a far superior German force, showed immense courage and determination, but he has subsequently been criticized as reckless. He could have avoided the battle that cost his life, but chose not to.

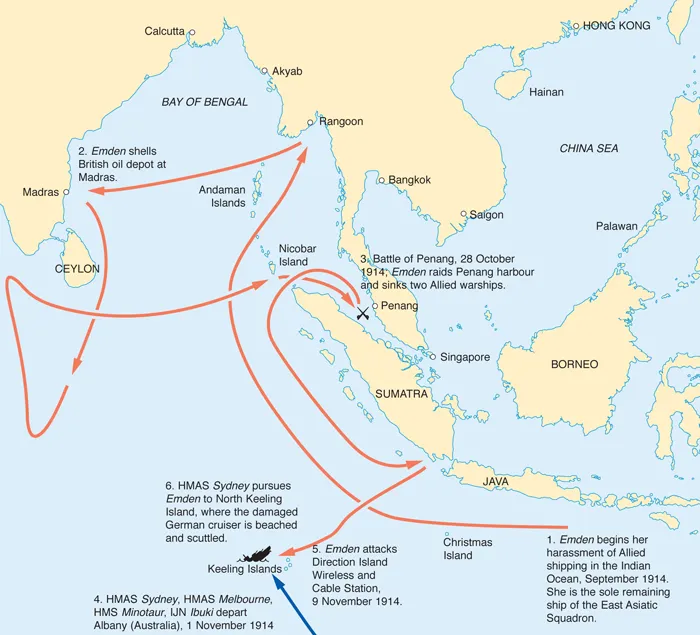

Spee’s orders gave him considerable freedom to act according to his own appreciation of the situation. At the start of the war, his squadron was scattered, but its core ships, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, together with the light cruiser Nürnberg, were training in the Caroline Islands. Spee led his force to Pagan Island in the Marianas, where he was met by the light cruiser Emden, escorting the supply ships and colliers (coaling ships) that had departed Tsingtao in anticipation of its being blockaded. He decided to keep his force concentrated rather than dispersing it. Some historians later suggested that he would have achieved more by splitting his force and having it prey on British shipping, to maximize disruption and to force Britain to disperse its navy to hunt each vessel down. However, Spee believed that keeping them together would prevent individual ships from being cornered and destroyed. Moreover, keeping the force concentrated offered him the prospect of engaging at an advantage a smaller enemy squadron. Some of his captains, particularly Karl von Müller of the light cruiser Emden, put the case for conducting classic cruiser warfare against British trade. Spee accepted that a single cruiser could cause significant disruption and would be able to refuel itself from captured vessels. He therefore detached Emden, as the fastest light cruiser, to attack British merchant shipping in the Indian Ocean.

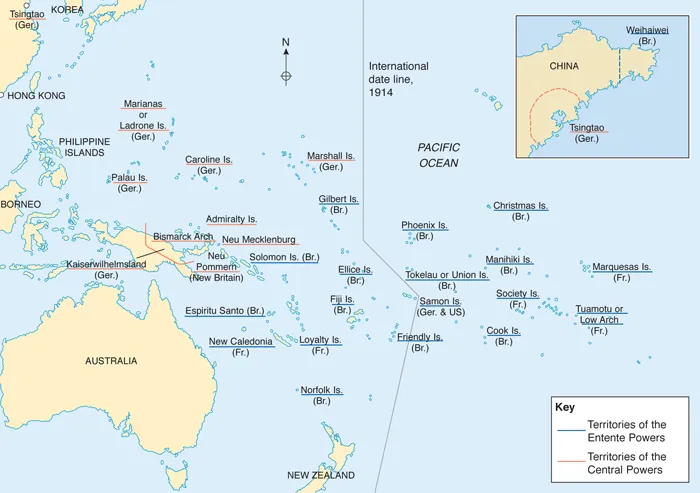

The Pacific, 1914. The naval balance in this region was generally favourable to the Entente powers, particularly after they were joined by Japan. Nevertheless, the sheer size of the area and the amount of shipping that needed protection meant that Allied naval forces would be stretched.

Spee was aware that British and Dominion forces were patrolling near Hong Kong and Australia, and had been warned that, at best, Japan would be neutral. This meant that the base at Tsingtao would be untenable and made the option of raiding British trade in East Asia unappealing. His decision proved prudent, as on 23 August Japan declared war on Germany. The rising power in Asia was keen to use the opportunity presented by the war in Europe to enhance its position in the Pacific, while its navy was equally eager to improve its prestige in comparison with the army. The Japanese Navy made a valuable contribution to the Allied cause, escorting convoys as far as Europe, as well as occupying German-owned islands in the Pacific, including the Carolines, Marianas and Marshalls, all names that would become familiar in the next world war. In September 1914, Japan launched an amphibious assault against Tsingtao. Her forces advanced over land, besieged the base and captured it in November. In the meantime, other German colonies were mopped up, with New Zealand seizing Samoa, and Australia taking New Guinea, New Britain and the Solomons.

Emden‘s area of operations. Spee was persuaded to allow the light cruiser Emden to separate from the rest of his squadron in order to raid enemy shipping in the Indian Ocean. She took 23 vessels and caused great disruption for two months before being sunk by HMAS Sydney.

The Pacific was therefore rapidly becoming hostile to German forces. However, it was to Spee’s advantage that many of the British and Allied warships in the area were occupied in supporting operations to capture German colonies (a far from urgent task, which could have waited until his force had been dealt with) and in escorting troop convoys heading for Europe. Despite the network of colliers and friendly agents in neutral ports built up by Germany before the war, the availability of fuel was the main consideration for Spee.

He therefore headed south and east, towards the coast of Chile, where he expected to be able to acquire coal. On the way, he was joined at Easter Island by the light cruisers Leipzig (which had steamed south from the coast of California) and Dresden (which had rounded Cape Horn, having been in the South Atlantic at the outbreak of war). Each had taken two British merchant ships before joining the main force. Spee then managed largely to disappear into the vast expanses of the southern Pacific. Britain had no firm idea of his location, but the best guess of naval commanders was that he was heading for South America, which was supported by occasional sightings of his force. On 14 September, he was spotted off Samoa; on 22 September, a French steamer radioed a sighting of the German ships at Tahiti; and in mid-October they were spotted at Easter Island. These sightings confirmed indications gleaned from intercepted wireless messages that he was heading for South America, though this was far from certain.

German Cruiser Operations

Accounts of naval warfare often focus on great clashes between fleets, but no less significant were the activities of cruisers. They patrolled the seas, often at some distance from home and for long periods, either defending or attacking merchant shipping. Targeting trade could damage an enemy’s economy and hinder his transportation of key war materials and troops, as well as forcing him to devote disproportionate resources in dispersing his fleet to hunt down the attackers. The American historian Alfred T. Mahan dismissed the impact of cruisers in harassing shipping, as opposed to a full blockade. Nevertheless, in the early months of World War I they tied down considerable Allied resources and brought some striking German successes.

German cruiser operations caused considerable disruption and achieved favourable publicity, but their impact was negligible next to that of the U-boats.

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock was in command of the North America and West Indies Squadron, responsible for a huge area with a great deal of merchant traffic. His squadron of cruisers was in the Caribbean at the outset of the war. It had been hunting German cruisers in the North Atlantic, but as the threat there declined and reinforcements arrived, it moved south. His forces were small relative to the vast area for which they were responsible, and though capable of taking on a raiding light cruiser, they were old and greatly inferior to Spee’s squadron. Cradock’s flagship was the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope, which displaced 14,325 tonnes (14,100 tons). Her two 9.2in guns were backed by 16 outdated 6in guns, although it was generally known that these low-mounted weapons could not be used in heavy seas, further weakening their offensive power. She was accompanied by the 9750-tonne (9600-ton) armoured cruiser Monmouth, carrying 14 of the same 6in guns. These cruisers were very much second-line warships, and had not been retained for service with the Grand Fleet precisely because of their age and limited armament. Furthermore, the policy of concentrating forces at home – which had involved disbanding the South Atlantic Squadron – and reinforcing overseas stations only on mobilization, meant that their crews were inexperienced reserves. The ships were supported by the more modern light cruiser Glasgow (4880 tonnes/4800 tons, armed with two 6in and ten 4in guns) and the armed merchant cruiser Otranto, which was expected to fight similar vessels among the enemy forces rather than warships. While the light cruisers on either s...