![]()

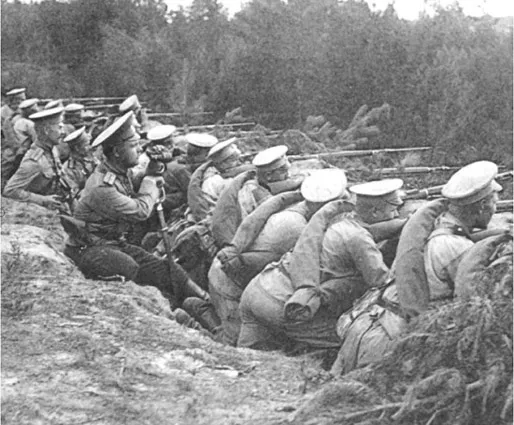

Russian infantrymen form a skirmish line early in the war. Russian officers were generally unimpressed with the quality of Russian soldiers, most of whom had little enthusiasm for the war and little identification with pan-Slavism.

CHAPTER 1

The First Battles

Russian leaders supported their country’s entry into World War I, hoping to recover their nation’s power and prestige in the Balkans. The first battles went much better than many Russians expected, especially against the Austro-Hungarians. But the Russian Army soon suffered massive twin defeats that underscored the fundamental weaknesses of the Russian system.

When war broke out in the first days of August, seven of Germany’s eight field armies headed west on their ill-fated attempt to knock France out of the war in six weeks. While the Germans moved through Belgium and into France as part of the Schlieffen Plan, the forces of Austria-Hungary began mobilization aimed at meeting the wide variety of threats the war presented to them. Conrad had designed a war plan that divided his army into three components: one to deal with Serbia, one to move into southern Poland to hold off the Russians and one in reserve that could go north or south depending on the events in the war’s opening phases. While the plan looked good on paper, it overloaded the Austro-Hungarian transportation and communications systems, and soon proved to be an unmanageable tangle. Many units had to march for days to get to their assigned train stations only to find that there were no available trains to take them to the front. Conrad also wanted to be careful about which ethnic groups he sent where. Thus many of the forces to fight the Serbs came from far-flung (but not Slavic) parts of the empire like Bohemia.

All of Germany and Austria-Hungary’s planning counted on the Russians mobilizing very slowly. Only a presumption of Russian ineptitude would have dared to allow Conrad to send the majority of his forces elsewhere. As the Germans, under Helmuth von Moltke, gambled on a quick defeat of France, so, too, did Conrad gamble on being able to eliminate Serbia quickly without significant Russian interference. Only 20 Austrian divisions went into Poland to guard against Russian movements. Both Moltke and Conrad had assumed that capturing the enemy capital would give them the victory they sought, thus enabling forces to be redirected in plenty of time to meet the Russians. Both men were to be seriously disappointed.

The large Polish Salient offered both opportunities and challenges to the Russians. They feared a joint German and Austro-Hungarian pincer attack on the salient, but also understood the advantages of assembling forces inside it.

Russia threw a giant spanner into all of the planning by Germany and Austria-Hungary, now known collectively with the Ottoman Empire as the Central Powers. In the first place, the Russian people met the Tsar’s call for mobilization on 30 July with an enthusiasm that few expected. This enthusiasm was mostly limited to young men in the growing Russian cities, but even so, thousands of young men joined the army and urban reservists reported to their units without much trouble. The Tsar made impassioned speeches to his people calling on all Russians to unite in a time of national crisis. Even in the countryside, peasants seemed to accept the necessity of the war, although they exhibited much less enthusiasm than the urbanites of Moscow and St Petersburg. The new Russian railways also came into play, as men and supplies moved from the hinterland of Russia to its mobilization centres with reasonable speed and efficiency. The Russians were still far behind the speed and efficiency of the Germans or the French, but all observers noted how much better the mobilization went than many Russians had feared.

‘The three Governments agree that when terms of peace come to be discussed, no one of the Allies will demand terms of peace without the previous agreement of each of the other Allies.’

Triple Entente declaration, 4 September 1914

Grand Duke Nikolai, the Tsar’s uncle, did not want the job of commander-in-chief. He believed he was ill suited to the task, despite a generally high reputation among Russian officers. He only accepted the position out of loyalty to his nephew the Tsar.

The key to the Russian mobilization plan lay in the central idea of a staged mobilization. Essentially, Russian planners had concluded that the immensity of their army and the size of Russia itself made it unwise to mobilize all resources first then deploy to the field. Doing so would simply overwhelm the rail network and the training camps at mobilization centres. Under the new plan, units would deploy into the field as soon as they were ready to do so. In a small country, such a plan would have risked placing too few men in the field to resist a determined enemy invasion. For the Russians, however, it meant that tens of thousands of men came into the field every week. The first divisions to be ready could go onto the offensive, while the second and third waves stood by to reinforce success, or, in a worst-case scenario, provide the required troops for a defence of the Russian homeland.

If the Central Powers had indeed coordinated their strategy and launched a joint invasion of Russia, it is unlikely that this mobilization scheme would have been equal to the task of defending Russia. The Russians had a badly exposed bump in their line known as the Polish Salient that the Germans and Austro-Hungarians could have hit simultaneously from the north and the south. But no such operation materialized as the Germans headed west and the Austro-Hungarians headed south, giving the Russians some much-needed space and time in which to. mobilize and deploy. It is entirely possible that the Russians knew the general outline of Central Powers planning: the Austro-Hungarian plans were likely slipped to them by Colonel Redl, their spy in the General Staff, and German intentions might well have been known from their French ally, who had divined the general outline of the Schlieffen Plan.

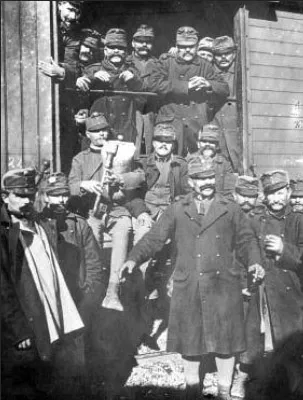

Austro-Hungarian soldiers, like these men, spoke a dizzying array of languages and came from dozens of often mutually antagonistic ethnic groups. This diversity imposed a special burden on the Austro-Hungarian mobilization process.

RUSSIAN WAR PLANS

What to do with the men that the Russians mobilized posed a different problem. The Russians had long assumed the need to fight both Germany and Austria-Hungary in the event of war, but the distances involved created tremendous challenges for Russian planners. The distance from Moscow to Berlin was 1860km (1156 miles) and the distance between Berlin and Vienna was 678km (421 miles), much too far away for a single campaign to encompass both enemy capitals. The terrain of Eastern Europe also posed challenges, as it possessed few railways and was generally lacking in the kinds of supplies an army needed on the march. Supply and logistics would present insurmountable challenges for a Russian general staff not well known for such skills.

In 1910, General Yuri Danilov proposed a solution to this dilemma. He discarded previous Russian war planning that had been based on the Napoleonic experience of withdrawing deep into Russian territory, sacrificing men and land and forcing the enemy to advance over poor terrain. Trading space for time had worked a century earlier, but Danilov thought the 1812 experience not worth repeating. Perhaps more importantly, he understood that times had changed and that a massive withdrawal into the Russian interior might have catastrophic consequences for Russian morale and the security of the Tsarist regime. He also knew that Russian and French generals had based their planning around coordinated offensive action against Germany to place pressure on the Germans from both the west and the east simultaneously. Russia would therefore need to throw away outmoded ways of thinking and develop an offensive war plan.

His solution became known as Plan 19, after the 19 army corps that he hoped to have ready to lead the first wave. Danilov had assumed that the Germans would attack France first, thus leaving East Prussia vulnerable. Two Russian armies would thus advance into East Prussia, a highly developed province that could provide food and fuel to an invading army. One of the Russian armies would then head toward Berlin while the other moved into mineral-rich Silesia. In the early phases of the war, the remaining Russian units would stay on the defensive around Russia’s outdated but still useful fortifications to repel any Austro-Hungarian attacks from the southwest. Once a sufficient number of units had mobilized in Ukraine, the Russian Army could also begin an offensive against Austria-Hungary along the Carpathian Mountains.

Residents in St Petersburg demonstrate in favour of the war during a brief display of national unity. The notoriously anti-Semitic Tsar even reached out to Russia’s Jews in 1914, but the mood of cooperation did not last.

The Balkan Wars

The first Balkan War saw Serbia and its allies, Bulgaria, Greece and Montenegro, capture the Ottoman provinces of Novibazar and Macedonia in 1912. The war pushed the Ottomans in Europe back to the Gallipoli Peninsula and a small bridgehead protecting the western approaches of Constantinople itself. The Russians looked on favourably and offered the Balkan League its support, but did not engage directly. In 1912–13 the Second Balkan War broke out among the members of the Balkan League for their share of the spoils. The wars were a complete humiliation for the Ottoman Empire and a moment of great triumph for a resurgent Serbia.

The unexpectedly rapid Russian mobilization gave Russian commanders the resources to launch two attacks at the same time. Within 15 days after the declaration of mobilization on 30 July, the Russians had 27 divisions ready for combat. A week later, another 25 divisions were ready for combat. In all there were 90 Russian divisions in Europe and 20 more divisions in the Caucasus theatre by 1 September. The Russian high command thus decided to launch the attack on East Prussia, but abandon the essentially defensive part of the plan in favour of immediate operations against Austria-Hungary’s belt of Carpathian fortifications that guarded the mountain passes into the agricultural heartland of the empire in northern Hungary.

As a result, Russia was prepared to send enormous forces against Germany and Austria-Hungary simultaneously while the Germans and Austro-Hungarians were looking the other way. If these forces had been intelligently led they might have done some serious damage. The Russian officer corps was, however, rife with personal and professional rivalries that made efficient command and control virtually impossible. Two mutually suspicious cliques had developed, one based around modernizers in the War Ministry, the other based around more traditional ideas in the army’s general staff. The rivalries had grown so intense that many senior Russian officers were barely on speaking terms with one another and many more had diametrically opposed views on the nature of war. It had become policy in Russia to deal with this rivalry by assigning officers from both cliques to the same headquarters staffs in an effort to force them to overcome their differences, but this approach had largely failed, instead reinforcing the rivalries and jealousies.

Given the factionalism and rivalries in the army, Nicholas II looked to find an overall commander who might be able to rise above the fray. Even as the armies were deploying into the field, he changed senior leadership, asking his uncle, the distinguished military veteran Grand Duke Nikolai, to assume command. Nikolai reluctantly agreed to his nephew’s request. Although widely respected for championing reform in the Russian Army, Nikolai had been out of the mainstream of Russian military thinking since 1909 and had only heard faint inklings of the details of Plan 19. Thus the first task of the new Russian commander was to find out exactly what his own army’s plans were. He soon discovered to his dismay that the army had made wholly inadequate preparations for communications in the field and that important logistical details had been ignored altogether. It was not an auspicious start for the new commander of the largest army in Europe.

RENNENKAMPF AND SAMSONOV

Nikolai knew that the primitive state of Russian communications would pose tremendous problems to any effort at centralized command and control. Almost all messages sent from his office to the front went first to Warsaw, where they were decoded then sent forward to army and corps commanders by messenger. This cumbersome system was designed in part to compensate for the simple codes the Russians used. Changing code books across a vast and expansive Russian empire proved to be so daunting a task that the Russians tended to rely on older codes, which greatly increased the chance of their being broken. Sending messages overland by courier was a distinctly nineteenth-century way of doing business, but it significantly reduced the chances that the Germans would intercept a message and either decode it or gain another clue into how to break the Russian code system.

This image of a Russian soldier disguises the poor quality of equipment that most new recruits received. The large but inefficient Russian industrial and transportation systems had difficulties keeping men supplied throughout the war.

The initial Russian success in mobilizing much faster than the Germans had anticipated allowed two Russian armies to threaten East Prussia, the traditional seat of the Prussian elite. The commander of the German Eighth Army therefore decided on a massive retreat.

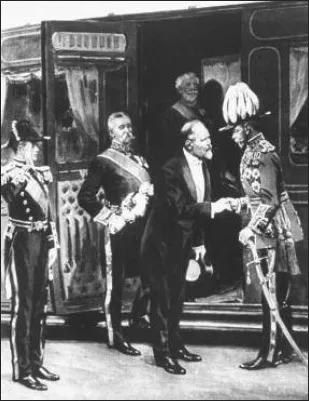

French President Raymond Poincaré meets King George V in a symbolic act of unity. Along with the Russians, the French and British determined not to seek a separate peace with Germany. Russia’s defeats, however, gave their allies concerns.

As a result of the Russian communications problems, command and control became unusually decentralized. While Moltke tried (with mixed results) to command the German Army from a field headquarters in Luxembourg and the French commander Joseph Joffre was able to monitor events and issue orders from his splendid headquarters in the Château de Chan...