Charles Darwin entered the scene when evolution was a pseudo-science. Given his careful attention to the methodologies of his day, it had obviously been Darwin’s hope that the Origin would elevate evolutionary studies to the level of a professional science, like physics and chemistry. He wanted natural selection to be a fruitful mechanism of inquiry. However, he failed in this aim. He convinced the world that evolution was a fact, but he did not succeed in persuading his fellow scientists that natural selection was an active and valuable tool of inquiry, giving us insights into the nature of organisms and their histories. It is true that there was some limited study of evolutionary morphology in the universities, but by and large, evolution was not a science for the professional scholar.

Evolution as popular science

To leave the story just like this would not do Darwin—or history—justice. We must turn now to the huge impact that the Origin and the Descent had on general culture. Evolution had not yet achieved the status of a professional science; it was, above all, the preeminent popular science—the science of the general domain. We see this most obviously in the new museums of natural history that were being built in Britain, on the continent, and particularly in the great cities of the United States of America. It was there that one went to see the wonderful panoramas of biological change—from primitive forms up through lesser animals until one reached the primates with humans at the peak. With the fabulous finds of fossil dinosaurs in the USA and Canada in the second half of the 19th century, museums became focal points of immense popular interest, playing the role of purveyors of popular science, which taught about the world and, at the same time, gave messages and understanding of moral, social, and religious issues.

After the enormous success of the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Crystal Palace was moved to a park in South London. In the grounds were placed models of dinosaurs, still there today. The brutes were shown as clumsy and massive, whereas now—as was shown in the movie Jurassic Park—there is the realization that many dinosaurs were agile and very active.

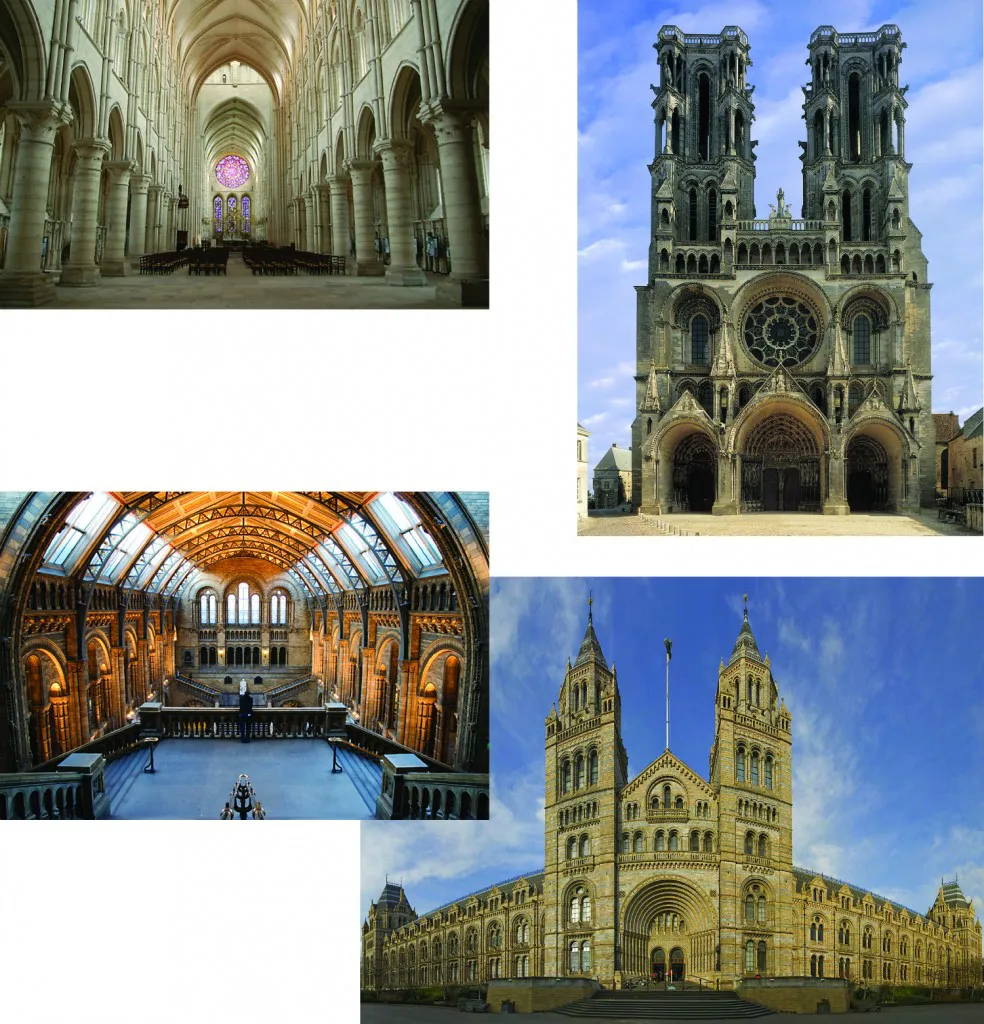

A conscious effort was made by the promoters of science like Thomas Henry Huxley to replace what they saw as their greatest rival, religion, especially the established Church of England. Consciously, natural history museums were modeled on Cathedrals, with the hope that instead of going to Communion on Sunday morning families would go to look at fossils and other fascinating and instructive objects on Sunday afternoons. This picture has the medieval Cathedral of Laon in France on top and the British Museum (Natural History) on the bottom.

Museums were for Sundays, the day of the family outing. What about the weekdays? This was before the advent of television, radio, and motion pictures. Universal literacy made enormous strides forward in the middle of the 19th century and the printed word—fiction and poetry—reigned supreme. Leading novelists like Charles Dickens and poets like Alfred Tennyson were lionized, and they, in turn, reflected and molded public opinion. We have seen already how a beginning novelist like Thomas Hardy—a man who read Darwin with enthusiasm when young and who continued to regard the Origin as most influential on his thinking—picked up and used evolutionary themes. Through the last decades of the 19th century, this major role of the fact of evolution continued strong. In several of his novels and short stories, H. G. Wells, a student of Thomas Henry Huxley, also toyed with evolutionary themes, most notably in the Time Machine, where he supposed that human evolution had gone on to produce two new species, the beautiful but idle Eloi living above ground and the hardworking, but vile Morlocks dwelling in caves below ground and preying on those living above in the open. Likewise, evolution underlined much of the happenings in the classic vampire novel, Dracula, in which an evil fiend showed all of the features of our simian past. And similar themes played out in works like Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, imagining an island of prehistoric beasts far away in South America. Incidentally, Conan Doyle’s most famous creation, Sherlock Holmes, was apparently ignorant of the Copernican system but was well up on his Darwin!

Selection

I have written about the failure of natural selection as a scientifically convincing mechanism. Not so in the world of many creative writers, who saw it as a truly liberating idea. For instance, George Gissing’s New Grub Street,—a story of struggling writers—explored the features needed for success or those that led to defeat, and how they played out together. This novel culminates with the loser dying and the winner marrying the loser’s widow. As noted in this work, “though she had never opened one of Darwin’s books, her knowledge of his main theories and illustrations was respectable.” Most over-heated of all are the tales of the American novelist Jack London, but one can see the raw power and how Darwin had changed our world. In his seminal novel, The Call of the Wild, London wrote:

Buck possessed a quality that made for greatness—imagination. He fought by instinct, but he could fight by head as well. He rushed, as though attempting the old shoulder trick, but at the last instant swept low to the snow and in. His teeth closed on Spitz’s left fore leg. There was a crunch of breaking bone, and the white dog faced him on three legs. Thrice he tried to knock him over, then repeated the trick and broke the right fore leg. Despite the pain and helplessness, Spitz struggled madly to keep up. He saw the silent circle, with gleaming eyes, lolling tongues, and silvery breaths drifting upward, closing in upon him as he had seen similar circles close in upon beaten antagonists in the past. Only this time he was the one who was beaten. There was no hope for him. Buck was inexorable. Mercy was a thing reserved for gentler climes.

Laugh in a condescending manner if you will, but the fact is that in its 100-year lifespan, this novel has never been out of print. At my last count, Amazon.com had over 30 different editions, and I am not separating hard- and soft-cover versions.

More subtle and perhaps more interesting was a novelist-poet like Hardy, who took away the message that the Darwinian mechanism was essentially unguided—the variations on which selection worked had no built-in teleology. In his novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles—a story with the high point in the penultimate paragraph where the heroine was hanged for murder, followed by the final paragraph where the hero went off with her sister and there was no felt need to remark that they would be unable to marry because such unions were banned by law—Hardy explored in unrelenting detail how fate offered no solace to the fragile human and how the meaningless of life could crush us all:

Upon the cornice of the tower a tall staff was fixed. Their eyes were riveted on it. A few minutes after the hour had struck something moved slowly up the staff, and extended itself upon the breeze. It was a black flag.

‘Justice’ was done, and the President of the Immortals, in Aeschylean phrase, had ended his sport with Tess. And the d’Urberville knights and dames slept on in their tombs unknowing. The two speechless gazers bent themselves down to the earth, as if in prayer, and remained thus a long time, absolutely motionless: the flag continued to wave silently. As soon as they had strength, they arose, joined hands again, and went on.

However, not everyone was quite this gloomy. And when it came to sexual selection, there was unbridled enthusiasm. Female protagonists in Gissing’s New Grub Street knew the score. This is how one of them described a young journalist, Jasper Milvain:

He was so human, and a youth of all but monastic seclusion had prepared her to love the man who aimed with frank energy at the joys of life. A taint of pedantry would have repelled her. She did not ask for high intellect or great attainments; but vivacity, courage, determination to succeed, were delightful to her senses.

It was widely accepted that Darwin had spotted something important, and every human being could take consolation in the fact that love had taken the course nature intended. Constance Naden, a lively English poet of the 1880s, had tremendous fun in her Evolutional Erotics. Her protagonist—a young lover—was sure he was destined for success—after all, he was a successful and hard-working junior scientist. But, as Naden noted in the poem, his qualifications were not impressive enough:

But there comes an idealess lad,

With a strut, and a stare, and a smirk;

And I watch, scientific though sad,

The Law of Selection at work.

Of Science he hasn’t a trace,

He seeks not the How and the Why,

But he sings with an amateur’s grace,

And he dances much better than I.

And we know the more dandified males

By dance and by song win their wives —

‘Tis a law that with Avis prevails,

And even in Homo survives.

In the end, the poor sap was left only with the reflection that science had predicted his fate all along:

Shall I rage as they whirl in the valse?

Shall I sneer as they carol and coo?

Ah no! for since Chloe is false,

I’m certain that Darwin is true!

Expectedly, there were those—like English poet May Kendall—who turned Darwin back on himself, arguing that, ultimately, his principles led to a sort of evolutionary feminism, as depicted in Kendall’s 1880s poem, Woman’s Future:

Complacent they tell us, hard hearts and derisive,

In vain is our ardour: in vain are our sighs:

Our intellects, bound by a limit decisive,

To the level of Homer’s may never arise.

We heed not the falsehood, the base innuendo,

The laws of the universe, these are our friends,

Our talents shall rise in a mighty crescendo,

We trust Evolution to make us amends!

Interestingly, the poem refers to Darwin’s fellow evolutionist, the previously mentioned Herbert Spencer:

Is this your vocation? My goal is another,

And empty and vain is the end you pursue.

In antimacassars the world you may smother;

But intellect marches o’er them and o’er you.

On Fashion’s vagaries your energies strewing,

Devoting your days to a rug or a screen,

Oh, rouse to a lifework — do something worth doing!

Invent a new planet, a flying-machine.

Mere charms superficial, mere feminine graces,

That fade or that flourish, no more you may prize;

But the knowledge of Newton will beam from your faces,

The soul of a Spencer will shine in your eyes.

Darwinism—and this means natural and sexual selection—was simply part of Victorian culture. An...