![]()

CHAPTER ONE

INFANTRY FIREPOWER

Although the modern infantry unit can draw upon a massive spectrum of firepower – including artillery, armoured support and aerial bombardment – it still needs to possess the fundamental skills of small-arms handling to be effective. Without such skills, the unit will be unable to effect the fire-and-manoeuvre tactics so central to competent war fighting, and it will also jeopardize its own safety should support resources not be available. As recent experience in Iraq and Afghanistan has shown, small-arms engagements still occur with great frequency in low-intensity and counter-insurgency warfare, as well as in open conflict, so personal weapons handling remains at the forefront of military training.

THE FAMILY OF WEAPONS

Military units deploy small arms within certain categories, each category complementing the other in terms of firepower and capabilities. The members of this family are: handguns, submachine-guns, rifles and machine-guns.

In military use, handguns have limited applications. Their low penetrative power, relatively poor accuracy and limited range of around 30m (98ft) make them inadequate weapons in substantial firefights. They are primarily used as backup weapons in case of main weapon failure and as precautionary side arms for situations where security issues are not pressing. Typical examples of modern military handguns are the Beretta Model 92 (the standard side arm of the US Army) and the Glock 17/18, both weapons in 9mm (.35in).

Submachine-guns are, in many ways, the least commonly deployed types of small arm in military units. The high rate of fire and low-powered pistol rounds used by weapons such as the 9mm Uzi and the 9mm Ingram Mac 10 make them lethal at very close ranges, but wildly inaccurate for aimed fire. However, Special Forces soldiers use high-quality submachine-guns such as Heckler & Koch’s MP5 family for urban counter-terrorist operations, where instant heavy firepower is useful. Beyond that, submachine-guns tend to be used in a similar way to pistols as backup weapons, particularly for armoured vehicle crews (the submachine-gun’s smaller dimensions ensure that it is easily stowed).

RIFLES

The rifle is the defining small-arms type within infantry units, and each soldier is issued with one as his standard weapon. Most military assault rifles today are either 5.56mm (.21in) firearms such as the US M16A2 and British SA80A2, or 7.62mm (.3in) weapons such as the FN FAL or the infamous AK-47/AKM. (Although even the AK family includes small-calibre rifles such as the 5.45mm AK-74.) Assault rifles command ranges of up to 500m (1640ft), and they provide accurate fire in semi-auto, burst or full-auto modes. By firing rifle cartridges producing muzzle velocities in the region of 1000m/sec (3280ft/sec), rifle rounds offer an increased penetrative capability against commonly encountered structures such as brickwork, plasterboard and thin metal plate, and also impart greater kinetic energy to a human target to increase take-down power.

A closer look at the M16A2 illustrates the qualities of the modern assault rifle more fully. The M16A2 is a 5.56mm (.223 Remington) rifle with a length of 100.6cm (39.63in) and a weight (loaded with its 30-round magazine) of some 3.99kg (8.79lb). Apart from the barrel and most of the operating parts, the M16A2 is made mostly of high-impact composite materials, which are extremely durable in field use. In combat, the M16A2 has two fire modes: single-shot or three-round burst. The former is used for accurate aimed fire at longer ranges, while the latter is used in intense, shorter-range engagements when the soldier needs to put out heavy suppressive fire. To keep the gun controllable in both modes, the M16A2 is fitted with a muzzle compensator, which reduces muzzle flip and also helps shield the muzzle flash from enemy eyes. The sights are of adjustable aperture type, which give respectable aimed fire out to ranges of around 300m (984ft), the standard factory setting for many military rifles.

Beyond rifles such as the M16 are the high-accuracy, longrange rifles issued to snipers. Calibre types for these weapons vary more significantly, from standard NATO-issue 7.62x51mm (.3x2in) weapons such as the Accuracy International L96A1 and the US M24 Sniper Weapon System (SWS), through to large-calibre rifles such as the .50-calibre Barrett M82A1.

Maximum ranges for these weapons – depending on the ammunition type – extend from around 800m (2624ft) to 2000m+ (6561ft+) for the .50-calibre weapons.

MACHINE-GUNS

At the top of the tree of infantry small arms are machine-guns. Machine-guns are primarily intended for heavy suppressive fire at area targets, and range from man-portable guns operated by a single individual through to massive, vehicle-mounted weapons. Machine-guns are broken down into three categories: light, medium and heavy machine-guns. Light machine-guns are designed for squad- or fire-team level portability, and today generally utilize the same ammunition types as standard infantry rifles to rationalize unit ammunition usage on the battlefield.

One of the most popular types in use is the FN Minimi, known in US forces as the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW) and in the British Army as 5.56mm (.21in) Light Machine-gun (LMG).

The Minimi fires the standard 5.56mm round used by many Western assault rifles, including the SA80 and M16, and has a cyclical rate of fire of between 700 and 1000rpm. Although the individual rounds carry no more destructive force than those fired from a standard rifle, such a heavy volume of fire makes the Minimi a powerful battlefield presence.

Medium machine-guns are physically larger weapons that fire full-power cartridges (i.e. rounds that have full-length cases). They are less man-portable and generally require a two-man team for operation. The best examples of this weapon class are the Belgian FN MAG and the US M60, both bipod-mounted (pintle mounts are available for vehicular use), belt-fed 7.62x51mm (.3x2in) guns with rates of fire up to 800rpm (in the case of the FN MAG). Medium machine-guns are used more in sustained-fire roles than light machine-guns; hence they have quick-change barrels to prevent dangerous overheating.

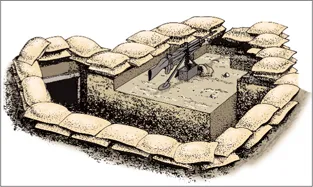

Like medium machine-guns, heavy machine-guns direct devastating fire against area targets, but tend to be used on vehicular mounts because of their great weight. The crowning example of a heavy machine-gun is the .50-calibre Browning M2HB, which can put dropping fire onto a target at ranges in excess of 3000m (9842ft). The reach and destructive force of a heavy machine-gun also categorizes it as an anti-materiel weapon, capable of destroying enemy vehicles, outposts and other structures.

The categories of small arms above are the fundamental tools of infantry warfare. In terms of tactical application, the modern soldier should be familiar with them all, and most good training programmes will provide training with the guns outside of the standard assault rifle.

CONTROLLING HANDGUN FIRE

Each individual weapon type has its own fire characteristics and effects. The soldier must master these before he can fully contribute to the power of a fire team.

Regarding handguns, the soldier has to develop a firing technique that maximizes the chances of a hit with what is a fairly inaccurate weapon. (Note here that all techniques relate to automatic handguns – modern soldiers rarely use revolvers.) Grip technique is all important. The firearm is held in the firing hand and the tension increased until the hand begins to tremble. At this point the hand is then relaxed until the trembling disappears – this is now the right grip tension. In terms of aiming hold, the two-handed grip is almost universally taught.

Here the fingers of the non-shooting hand are either wrapped around the fingers of grip hand at the pistol grip, or are cupped beneath the pistol grip to form a ‘cup and saucer’ grip.

Using the non-firing hand for support stabilizes the gun, reducing both horizontal and vertical movement, and also gives the shooter better body alignment with the target. Using isometric tension between the two hands enhances this stability: the hands pull in opposite directions, creating a tension that improves the rigidity of the hold and braces the arms against recoil.

SIGHTING PROCEDURES

Because handguns are such inaccurate weapons, good sighting procedures are essential for their use. Handgun sights are relatively crude, most having a simple rear notch and corresponding front post. For this reason, handgun training always recommends targeting the very centre of the enemy’s torso to maximize the chances of a decisive hit on a vital organ system. For sighted shooting – when there is time to take an aim – the front post sight is aimed directly at the centre mass; the rear sight and target will appear hazy, but concentration on the front post will give the best sense of accurate direction. When the target is on, the trigger is squeezed. It is vital that the soldier does not anticipate the gun’s recoil, as this often results in dipping the barrel to compensate, which produces low patterns. Of course, combat reality often necessitates that a soldier take shots extremely rapidly without considered aim. In this instance, the soldier should aim the gun instinctively like a pointed finger, directing all his focus at the intended point of impact on the target. Extending the index finger of the support hand along the side of the gun (not along the slide, which would inflict a finger injury as it cycles) aids this process – the soldier simply points at the target with his finger and that is generally where the rounds will go.

VOLUME OF FIRE

In terms of volume of fire, there has been much debate around handgun technique. Many police and military forces have advocated the ‘double tap’ principle – shoot the enemy twice quickly in the torso to ensure that he goes down. However, combat experience has shown that even being hit by two .45 calibre bullets does not guarantee a takedown. Therefore the ‘shoot to stop’ principle is now commonly taught. This simply involves putting as many rounds as pos...