![]()

Part I:

Tools and Techniques

![]()

1 | The Head Picture: Engaging Children in Incident-Specific Trauma Treatment By Anna Foley, Clinical Director, Moorside Trauma Service, England |

Engaging children in trauma treatment is primarily about helping them to talk about trauma, its symptoms, and its effects. Communicating information about stress reactions and the concept of mental/emotional treatment in an age-appropriate manner is crucial in showing that one can contain the horrors of trauma, and that one can be someone who will be able to help. This chapter lays out a technique I call ‘The Head Picture’. I have been using it for over 10 years with child and adult clients, and have taught it to diverse audiences. It has never failed in improving the ‘take up’ of information in the clinical setting, when children and families are in crisis.

Inspiration for ‘The Head Picture’

Without doubt my initial inspiration for this technique was Linda Chapman of Art Therapy Institute of the Redwoods (California), followed by the work of Robert Pynoos and Bessel van der Kolk.

The previous two decades have seen increasing evidence of the neurobiology of trauma. This has prompted my questioning of every aspect of my practice with traumatized children. The evidence regarding effects on the brain has revealed that areas associated with speech are reduced in size and functioning in traumatized children. This finding suggested to me that I ought to include information beyond the verbal realm in my communications with traumatized children and their families. I found that using images as well as speech has helped to demystify scary symptoms more efficiently and effectively. The impaired functioning after trauma also made me consider how one goes about gaining informed consent1 from children and families. Informed consent with children is often difficult to obtain, but using words alone makes it doubly difficult. The use of images to convey post-traumatic stress reactions and therapy has been invaluable in getting to the point where the client is understood and feels understood, in gaining a more informed consent, and in providing ways to measure a child's progress during therapy.

According to the Gerbode (1995) model (See Chapter 14), the TIR method is, “…in fact primarily educational in its intent.” This differs from the traditional medical model of treatment vs. disease2.

Starting as you intend to go on: handling the first appointment

If you work to get across an understanding of the concepts of stress and therapy, and set up an environment based on sharing knowledge and feelings, then the child is implicitly involved throughout. Children respond well to concrete examples of stress and its effects. Having been out of control during the traumatic experience, they need to receive useful knowledge and models from us so that they can separate their post-trauma reaction from themselves as people. If children are left with post trauma symptoms, they blame themselves for their inability to recover. This idea affects their self-esteem, and if left unaddressed, becomes an entrenched core belief. Entrenched shame is emotionally crippling and prolongs both suffering and trauma treatment. For complex traumas, this psychoeducation becomes a substantial part of the child's experience.

From the very first meeting, I convey that I welcome more than one way for the child to communicate with me. Another interpretation of this psychoeducation is that children are provided with something tangible. The picture they draw acts as an ‘internalized transitional object’ (many children take their drawing away with them), which they can use to externalize their post trauma symptoms.

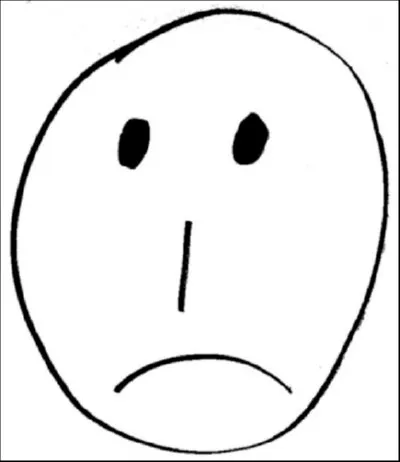

Fig. 1-1: Self-Image after an Incident (Head Picture)

‘The Head Picture’

This is how I talk to children and families about trauma

T denotes me as therapist, C denotes child.

I might offer the child the choice of color as we pick out a felt-tip pen. I draw a simple picture of a sad face, sometimes just a line for the mouth if I am being cautious not to assume I know what the child is feeling.

T. “Let's say that this is you. I know it's not really anything like you; I'm not the best at drawing (usually prompts a smile). Let's say that this is you right after you were _________” (See Fig. 1-1.) Here I will ascertain how the child describes or thinks of the traumatic experience: “stabbed,” “shot,” “beaten up,” “attacked,” etc. For complex trauma I generalize the stresses to be “After all that's happened to you.”)

The simple drawing and the fact it isn't perfect convey to the child that s/he does not have to be good at art to enter trauma treatment. I find children usually come with the pre-conceived idea that they have to do well, like at school. It is a good time also to tell the child that I am not a teacher.

Using the image gives them something to focus on while they are amid the anxiety of symptoms and the trepidation of the first appointment. Children and families visibly relax and are more receptive as soon as they see this ‘funny’ translation of stress into image.

The image sharing also allows a pacing which is fundamental in trauma treatment. In the introduction to treatment, I am attentive to the child's hyper-arousal, and watch carefully for raised heartbeat, sweaty palms, heightened startle response, etc. This gives me the opportunity to show the child and parent/caregivers how to calm themselves during post trauma arousal. It's crucial to show that treatment is paced so as to be tolerable to the child/client, and also to show that I expect these types of physiological changes to happen. Children then appear more able to actually talk about these symptoms during sessions.

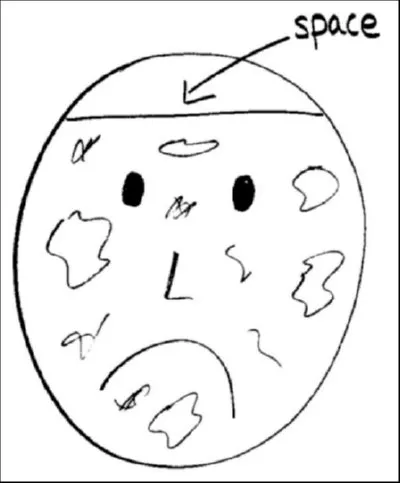

Fig. 1-2: Running Out of Space (Head Picture)

As a result of the psychoeducation beforehand, explaining to the child what we are going to do and what to expect, we are able to ‘track sensation’ during any exposure to the event(s) or other triggers that might arise.

T. “When someone is ‘attacked’ like you were, they find that they have lots and lots of thoughts, feelings and memories rushing round their mind, and body. Let's say these squiggly bits are all those different things (see Fig. 1-2). All different shapes and sizes, some small, some big, all feel different and some worse than others”. (Usually child and parent are nodding.) “Is that how it is for you?”

I allow time to answer, and lots of information is shared at this point. This might have been the first time the family can begin to make some sense of what they have experienced and changes that they have noticed. I can also observe any stilted communications between family members, which the psychoeducation element of the therapy may help to overcome.

C.“Yeah, there's just all this stuff.”

T.“When your head is busy trying to work out all of this stuff, it has only this little bit of space at the top, to think with or do things, that isn't full up of things already. So, when mum, dad or whoever asks you to do something like tidy your room, or do your homework, your little space becomes filled up and boom you ‘explode’. Or you might get really cross…”

C. “That's what I do!” (If the parents are there, they invariably say that the child wasn't like this before and he/she is now so hard to get on with, or that the simplest thing can trigger a rage.)

T.“Well, you see, there's only this little bit of space to deal with everyday things, so when something else comes along, it sits in this little space; it fills it up, and Wham! Anger is usually the first reaction!” (I go on to say that I'm not saying you should not do your homework or should break family rules, but that just now it's hard for you to follow them.) “Mum, you might find that your head feels a little like this too, since you've had a great deal of stress to deal with also.”

There is usually some discussion about how their family household is responding. It is pretty common from my experience that after a traumatic experience children appear extremely insecure, and don't want to leave their parents’ side, or are withdrawing to their bedrooms much more than before.

Fig. 1-3: Anger as a Result of Insufficient Space (Head Picture)

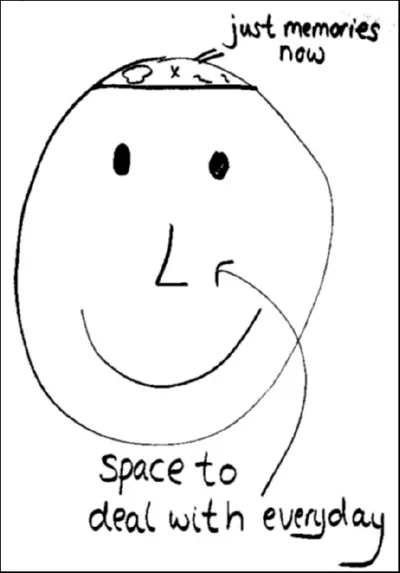

Fig. 1-4: After Initial Therapy (Head Picture)

Fig. 1-5: After Initial Therapy Sessions are Complete

This is also an opportunity to explore the meaning of all the stuff they feel in their head and to include places in the body where there may be sensations or emotions. This is important so that we encapsulate the true impact of traumatic experience. Sometimes I might actually draw out a body outline.

T. “So this is a little like what it might feel like inside your head and your body. When someone like you comes to see someone like me, we do a little bit of looking at these different things. Sometime we might manage to do a couple of these things, sometimes only one or a bit of one. Sometimes by looking at one thing, another thing seems to disappear by accident.”

T. “As time goes by, and you come here a few times, we will work together to make this space get bigger and bigger, and then you'll notice that everyday things get a bit easier; you'll have more and more space to do all your everyday things.”

Most times children volunteer what the squiggles actually represent for them. It's useful also to put the trauma in relation to other stresses in their life. This usually includes other traumatic events, school issues, issues with parents, friends, etc.

T. “What we're aiming for when we do this work is to get to a time when you have lots of space to deal with your everyday things, and the terrible thing that has happened to you doesn't take up all the space in your head. It becomes a memory that doesn't hurt or frighten you like it does now. We can flip the ‘Head Picture’ over so that the big space is for you, and the little space is for the memories.” (See Fig. 1-6)

Summary

If a child is consumed with anxiety around mummy leaving, worries about dying, nightmares, flashbulb or flashback memories, etc., then the child is unable to process fully what you are telling him or her. The therapist must demonstrate for the child that the therapeutic space is contained, that the therapist knows something about what the child is going through, and she or he is providing a way through the horror that doesn't necessarily need words. The therapist is providing a general tool to ascertain a unique trauma reaction. It also gives the family as a whole something to focus on and gives a tangible way of discussing stress together, whilst I'm not there to support that discussion.

Fig. 1-6: Just a Memory (Head Picture)

The Head Picture as a measuring tool for children

The head picture also provides a way for children to reflect on their therapeutic goals. It gives the child and me a measuring tool, which can change over time. Shapes and sizes of things change, may become fewer, or even become more for a time, if there are other stressors in the child's life during treatment. Externalizing them to image form seems to produce a sense of management, mastery of expressed emotions, and encourages more calm.

A Child will often say…

C. “Do you remember ‘The Head Picture’ you showed me?”

T. ‘“Yes, I remember.”

C. “It looks more like this now.” The child will invariably grab some paper and replicate the image and show that there is less ‘stuff’ in there.

I always double check this, and ask:

T. “Well OK great, we know it's not empty so what's in there now?” I am just checking out for anything left, and also conveying how ordinarily we have things that we think about or that trouble us, but that these everyday things are different from trauma.

A teenager I was working with after numerous gang attacks including beatings said at the end of his treatment, “My Dad still won't buy me a motorbike.” I replied, “Crumbs! I might be an OK therapist, but I'm not that good. I'm afraid that you and your dad will have to sort that one out.” He laughed, saying, “That's a shame. It was worth a try…”

To close the sessions I might offer the pen pot for the child to choose one, and ask him or her to put the trauma in the picture. It's usually the tiniest mark or shape and this gives me the opportunity to say “It's a memory now.” (See Fig. 1-6)

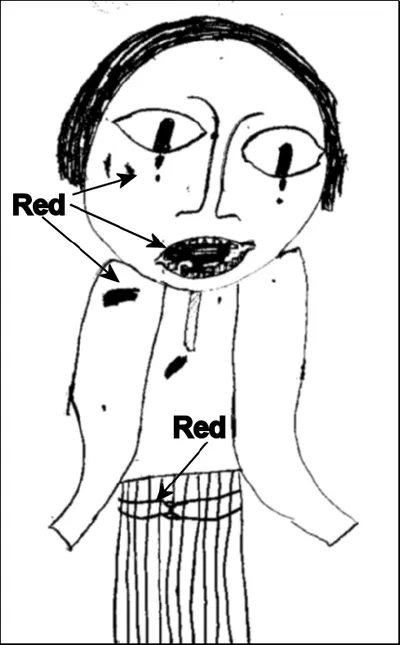

Body Outline Images

Fig. 1-7 (on the following page) is the self-portrait made by a 13-year-old girl referred for TIR after being attacked by a gang of girls her own age, and having her tooth broken. This image imparts to the viewer that more has happened to this girl. Feelings in differing parts of her body are signified by red blobs, and the lines and ‘belt’ around her waist. It transpired that she had been raped many years before whilst in the care of the extended family, which was disclosed through images during and after running through TIR in image form.

Fig. 1-7: Self-portrait of 13-year-old girl after gang attack

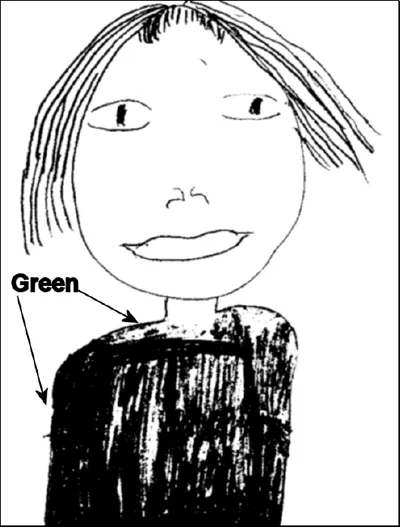

Fig. 1-8: Self-portrait of 13-year-old girl after therapy

Fig. 1-8 is a self-portrait that was produced after the initial incident was desensitized and older incidents were found and worked through in the same way.

Some examples of common symptoms that often arise amongst the scribbles, big and small

How would we discuss the symptoms with words alone?

- Intrusive re-experiencing: Images flashing in mind (“flashbulb memories”, or flashbacks).

- Autonomic hyper-arous...